Subway Map of the Exact Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

Jewels in the Crown

Jewels in the crown CSHL’s 8 Nobel laureates Eight scientists who have worked at Cold Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria Spring Harbor Laboratory over its first 125 years have earned the ultimate Beginning in 1941, two scientists, both refugees of European honor, the Nobel Prize for Physiology fascism, began spending their summers doing research at Cold or Medicine. Some have been full- Spring Harbor. In this idyllic setting, the pair—who had full-time time faculty members; others came appointments elsewhere—explored the deep mystery of genetics to the Lab to do summer research by exploiting the simplicity of tiny viruses called bacteriophages, or a postdoctoral fellowship. Two, or phages, which infect bacteria. Max Delbrück and Salvador who performed experiments at Luria, original protagonists in what came to be called the Phage the Lab as part of the historic Group, were at the center of a movement whose members made Phage Group, later served as seminal discoveries that launched the revolutionary field of mo- Directors. lecular genetics. Their distinctive math- and physics-oriented ap- Peter Tarr proach to biology, partly a reflection of Delbrück’s physics train- ing, was propagated far and wide via the famous Phage Course that Delbrück first taught in 1945. The famous Luria-Delbrück experiment of 1943 showed that genetic mutations occur ran- domly in bacteria, not necessarily in response to selection. The pair also showed that resistance was a heritable trait in the tiny organisms. Delbrück and Luria, along with Alfred Hershey, were awarded a Nobel Prize in 1969 “for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses.” Barbara McClintock Alfred Hershey Today we know that “jumping genes”—transposable elements (TEs)—are littered everywhere, like so much Alfred Hershey first came to Cold Spring Harbor to participate in Phage Group wreckage, in the chromosomes of every organism. -

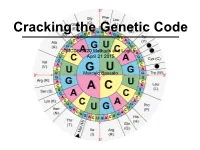

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick Discovered the Structure of DNA in the Now-Famous Scientific Narrative Known As the “Race Towards the Double Helix”

THE NARRATIVES OF SCIENCE: LITERARY THEORY AND DISCOVERY IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY PRIYA VENKATESAN In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA in the now-famous scientific narrative known as the “race towards the double helix”. Meanwhile in France, Roland Barthes published his first book, Writing Degree Zero, on literary theory, which became the intellectual precursor for the new human sciences that were developing based on Saussurean linguistics. The discovery by Watson and Crick of the double helix marked a definitive turning point in the development of the life sciences, paving the way for the articulation of the genetic code and the emergence of molecular biology. The publication by Barthes was no less significant, since it served as an exemplar for elucidating how literary narratives are structured and for formulating how textual material is constructed. As Françoise Dosse notes, Writing Degree Zero “received unanimous acclaim and quickly became a symptom of new literary demands, a break with tradition”.1 Both the work of Roland Barthes and Watson and Crick served as paradigms in their respective fields. Semiotics, the field of textual analysis as developed by Barthes in Writing Degree Zero, offered a new direction in the structuring of narrative whereby each distinct unit in a story formed a “code” or “isotopy” that categorizes the formal elements of the story. The historical concurrence of the discovery of the double helix and the publication of Writing Degree Zero may be mere coincidence, but this essay is an exploration of the intellectual influence that both events may have had on each other, since both the discovery of the double helix and Barthes’ publication gave expression to the new forms of knowledge 1 Françoise Dosse, History of Structuralism: The Rising Sign, 1945-1966, trans. -

James Watson and Francis Crick

James Watson and Francis Crick https://www.ducksters.com/biography/scientists/watson_and_crick.php biographyjameswatsonandfranciscrick.mp3 Occupation: Molecular biologists Born: Crick: June 8, 1916 Watson: April 6, 1928 Died: Crick: July 28, 2004 Watson: Still alive Best known for: Discovering the structure of DNA Biography: James Watson James Watson was born on April 6, 1928 in Chicago, Illinois. He was a very intelligent child. He graduated high school early and attended the University of Chicago at the age of fifteen. James loved birds and initially studied ornithology (the study of birds) at college. He later changed his specialty to genetics. In 1950, at the age of 22, Watson received his PhD in zoology from the University of Indiana. James Watson and Francis Crick https://www.ducksters.com/biography/scientists/watson_and_crick.php James D. Watson. Source: National Institutes of Health In 1951, Watson went to Cambridge, England to work in the Cavendish Laboratory in order to study the structure of DNA. There he met another scientist named Francis Crick. Watson and Crick found they had the same interests. They began working together. In 1953 they published the structure of the DNA molecule. This discovery became one of the most important scientific discoveries of the 20th century. Watson (along with Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962 for the discovery of the DNA structure. He continued his research into genetics writing several textbooks as well as the bestselling book The Double Helix which chronicled the famous discovery. Watson later served as director of the Cold Spring Harbor Lab in New York where he led groundbreaking research into cancer. -

From Controlling Elements to Transposons: Barbara Mcclintock and the Nobel Prize Nathaniel C

454 Forum TRENDS in Biochemical Sciences Vol.26 No.7 July 2001 Historical Perspective From controlling elements to transposons: Barbara McClintock and the Nobel Prize Nathaniel C. Comfort Why did it take so long for Barbara correspondence. From these and other to prevent her controlling elements from McClintock (Fig. 1) to win the Nobel Prize? materials, we can reconstruct the events moving because their effects were difficult In the mid-1940s, McClintock discovered leading up to the 1983 prize*. to study when they jumped around. She genetic transposition in maize. She What today are known as transposable never had any inclination to pursue the published her results over several years elements, McClintock called ‘controlling biochemistry of transposition. and, in 1951, gave a famous presentation elements’. During the years 1945–1946, at Current understanding of how gene at the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium, the Carnegie Dept of Genetics, Cold activity is regulated, of course, springs yet it took until 1983 for her to win a Nobel Spring Harbor, McClintock discovered a from the operon, François Jacob and Prize. The delay is widely attributed to a pair of genetic loci in maize that seemed to Jacques Monod’s 1960 model of a block of combination of gender bias and gendered trigger spontaneous and reversible structural genes under the control of an science. McClintock’s results were not mutations in what had been ordinary, adjacent set of regulatory genes (Fig. 2). accepted, the story goes, because women stable alleles. In the term of the day, they Though subsequent studies revealed in science are marginalized, because the made stable alleles into ‘mutable’ ones. -

Cover June 2011

z NOBEL LAUREATES IN Qui DNA RESEARCH n u SANGRAM KESHARI LENKA & CHINMOYEE MAHARANA F 1. Who got the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1933) for discovering the famous concept that says chromosomes carry genes? a. Gregor Johann Mendel b. Thomas Hunt Morgan c. Aristotle d. Charles Darwin 5. Name the Nobel laureate (1959) for his discovery of the mechanisms in the biological 2. The concept of Mutations synthesis of ribonucleic acid and are changes in genetic deoxyribonucleic acid? information” awarded him a. Arthur Kornberg b. Har Gobind Khorana the Nobel Prize in 1946: c. Roger D. Kornberg d. James D. Watson a. Hermann Muller b. M.F. Perutz c. James D. Watson 6. Discovery of the DNA double helix fetched them d. Har Gobind Khorana the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1962). a. Francis Crick, James Watson, Rosalind Elsie Franklin b. Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Willkins c. James Watson, Maurice Willkins, Rosalind Elsie Franklin 3. Identify the discoverer and d. Maurice Willkins, Rosalind Elsie Franklin and Francis Crick Nobel laureate of 1958 who found DNA in bacteria and viruses. a. Louis Pasteur b. Alexander Fleming c. Joshua Lederberg d. Roger D. Kornberg 4. A direct link between genes and enzymatic reactions, known as the famous “one gene, one enzyme” hypothesis, was put forth by these 7. They developed the theory of genetic regulatory scientists who shared the Nobel Prize in mechanisms, showing how, on a molecular level, Physiology or Medicine, 1958. certain genes are activated and suppressed. Name a. George Wells Beadle and Edward Lawrie Tatum these famous Nobel laureates of 1965. -

Biographical Notes on Scientists Involved in the Asilomar Process M.J

International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering Case Study Series: Asilomar Conference on Laboratory Precautions Appendix D: Biographical Notes on Scientists involved in the Asilomar Process M.J. Peterson Version 1, June 2010 Edward A. Adelberg (1920-2009). PhD Yale 1949. Chair of Yale Department of Microbiology 1961-64 and 1970-72; a founding member of Yale Department of Genetics. Deputy Provost for the Biomedical Sciences, 1983-91. Specialist in plasmid biochemistry of E. coli. Ephraim Anderson (1911-2006). M.D., Durham University. Served in the Royal Army Medical Corps during World War II where he developed interests in Epidemiology. Researcher in Enteric Laboratory of the British Public Health Laboratory Service 1947, Deputy Director 1952, Director 1954-1978. Came to public notice for tracing sources of typhoid outbreaks in Zermatt (1963) and Aberdeen (1964). Built on earlier work by Japanese researchers to demonstrate the plasmid-based pathways by which bacteria could spread antibiotic resistance to others and became the world’s leading expert on antibiotic resistance. Also prominent in efforts to limit use of antibiotics in raising animals. Fellow of the Royal Society 1968; Companion of the Order of the British Empire 1976. Eric Ashby, Baron Ashby (1904-1992). Lecturer in Botany, Imperial College London 1931-35; Reader in Botany Bristol University 1935-37; Professor of Botany University of Sydney 1938-1946; Chair of Botany, University of Manchester 1947-50. Turned to administration as President and Vice-Chancellor of Queen's University, Belfast 1950-59; Master of Clare College in Cambridge University 1959-67 and Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University 1967-1969. -

Members of Groups Central to the Scientists' Debates About Rdna

International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering Case Study Series: Asilomar Conference on Laboratory Precautions Appendix C: Members of Groups Central to the Scientists’ Debates about rDNA Research 1973-76 M.J. Peterson Version 1, June 2010 Signers of Singer-Söll Letter 1973 Maxine Singer Dieter Söll Signers of Berg Letter 1974 Paul Berg David Baltimore Herbert Boyer Stanley Cohen Ronald Davis David S. Hogness Daniel Nathans Richard O. Roblin III James Watson Sherman Weissman Norton D. Zinder Organizing Committee for the Asilomar Conference David Baltimore Paul Berg Sydney Brenner Richard O. Roblin III Maxine Singer This case was created by the International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering (IDEESE) Project at the University of Massachusetts Amherst with support from the National Science Foundation under grant number 0734887. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. More information about the IDEESE and copies of its modules can be found at http://www.umass.edu/sts/ethics. This case should be cited as: M.J. Peterson. 2010. “Asilomar Conference on Laboratory Precautions When Conducting Recombinant DNA Research.” International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering. Available www.umass.edu/sts/ethics. © 2010 IDEESE Project Appendix C Working Groups for the Asilomar Conference Plasmids Richard Novick (Chair) Royston C. Clowes (Institute for Molecular Biology, University of Texas at Dallas) Stanley N. Cohen Roy Curtiss III Stanley Falkow Eukaryotes Donald Brown (Chair) Sydney Brenner Robert H. Burris (Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin) Dana Carroll (Department of Embryology, Carnegie Institution, Baltimore) Ronald W. -

1 Are We Ready for Genome Editing in Human Embryos for CLINICAL

Are we ready for genome editing in human embryos FOR CLINICAL PURPOSES? Joyce C Harper and Gerald Schatten Joyce C Harper, Professor of Reproductive Science, Institute for Women’s Health, University College Londona Gerald Schatten, Professor of Ob-Gyn-Repro Sci, Cell Biology and Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicineb aInstitute for Women’s Health, University College London, 86-96 Chenies Mews, London, WC1E 6HX, UK, 0044 7880 795791, [email protected] (Corresponding author) b204 Craft Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15213 412/641-2403 [phone] 412/641-6342 [fax] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Perhaps the two most significant pioneering biomedical discoveries with immediate clinical implications during the past forty years have been the advent of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) and the genetics revolution. ART, including in vitro fertilization (IVF), intracytoplasmic sperm injection and preimplantation genetic testing, has resulted in the birth of more than 8 million children, and the pioneer of IVF, Professor Bob Edwards, was awarded the 2010 Nobel Prize. The genetics revolution has resulted in our genomes being sequenced and many of the molecular mechanisms understood, and technologies for genomic editing have been developed. With the combination of nearly routine ART protocols for healthy conceptions together with almost error- free, inexpensive and simple methods for genetic modification, the question “Are we ready for genome editing in human embryos FOR CLINICAL PURPOSES?” was debated at the 5th Congress on Controversies in Preconception, Preimplantation and Prenatal Genetic Diagnosis, in collaboration with the Ovarian Club Meeting, in November 2018 in Paris. The co-authors each presented scientific, medical and bioethical backgrounds, and the debate was chaired by Professor Alan Handyside. -

6 Women Scientists Who Were Snubbed Due to Sexism Despite Enormous Progress in Recent Decades, Women Still Have to Deal with Biases Against Them in the Sciences

6 Women Scientists Who Were Snubbed Due to Sexism Despite enormous progress in recent decades, women still have to deal with biases against them in the sciences. BY JANE J. LEE, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC PUBLISHED MAY 19, 2013 In April, National Geographic News published a story about the letter in which scientist Francis Crick described DNA to his 12-year-old son. In 1962, Crick was awarded a Nobel Prize for discovering the structure of DNA, along with fellow scientists James Watson and Maurice Wilkins. Several people posted comments about our story that noted one name was missing from the Nobel roster: Rosalind Franklin, a British biophysicist who also studied DNA. Her data were critical to Crick and Watson's work. But it turns out that Franklin would not have been eligible for the prize—she had passed away four years before Watson, Crick, and Wilkins received the prize, and the Nobel is never awarded posthumously. But even if she had been alive, she may still have been overlooked. Like many women scientists, Franklin was robbed of recognition throughout her career (See her section below for details.) She was not the first woman to have endured indignities in the male- dominated world of science, but Franklin's case is especially egregious, said Ruth Lewin Sime, a retired chemistry professor at Sacramento City College who has written on women in science. Over the centuries, female researchers have had to work as "volunteer" faculty members, seen credit for significant discoveries they've made assigned to male colleagues, and been written out of textbooks. -

Open Letter to the American People

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: October 18, 2016 AN OPEN LETTER TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE The coming Presidential election will have profound consequences for the future of our country and the world. To preserve our freedoms, protect our constitutional government, safeguard our national security, and ensure that all members of our nation will be able to work together for a better future, it is imperative that Hillary Clinton be elected as the next President of the United States. Some of the most pressing problems that the new President will face — the devastating effects of debilitating diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and cancer, the need for alternative sources of energy, and climate change and its consequences — require vigorous support for science and technology and the assurance that scientific knowledge will inform public policy. Such support is essential to this country’s economic future, its health, its security, and its prestige. Strong advocacy for science agencies, initiatives to promote innovation, and sensible immigration and education policies are crucial to the continued preeminence of the U.S. scientific work force. We need a President who will support and advance policies that will enable science and technology to flourish in our country and to provide the basis of important policy decisions. For these reasons and others, we, as U.S. Nobel Laureates concerned about the future of our nation, strongly and fully support Hillary Clinton to be the President of the United States. Peter Agre, Chemistry 2003 Carol W. Greider, Medicine 2009 Sidney Altman, Chemistry 1989 David J. Gross, Physics 2004 Philip W. Anderson, Physics 1977 Roger Guillemin, Medicine 1977 Kenneth J.