The Blessed Vision of Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT Love Itself Is Understanding: Balthasar, Truth, and the Saints Matthew A. Moser, Ph.D. Mentor: Peter M. Candler, Jr., P

ABSTRACT Love Itself is Understanding: Balthasar, Truth, and the Saints Matthew A. Moser, Ph.D. Mentor: Peter M. Candler, Jr., Ph.D. This study examines the thought of Hans Urs von Balthasar on the post-Scholastic separation between dogmatic theology and the spirituality of Church, which he describes as the loss of the saints. Balthasar conceives of this separation as a shattering of truth — the “living exposition of theory in practice and of knowledge carried into action.” The consequence of this shattering is the impoverishment of both divine and creaturely truth. This dissertation identifies Balthasar’s attempt to overcome this divorce between theology and spirituality as a driving theme of his Theo-Logic by arguing that the “truth of Being” — divine and creaturely — is most fundamentally the love revealed by Jesus Christ, and is therefore best known by the saints. Balthasar’s attempted re-integration of speculative theology and spirituality through his theology of the saints serves as his critical response to the metaphysics of German Idealism that elevated thought over love, and, by so doing, lost the transcendental properties of Being: beauty, goodness, and truth. Balthasar constructively responds to this problem by re-appropriating the ancient and medieval spiritual tradition of the saints, as interpreted through his own theological master, Ignatius of Loyola, to develop a trinitarian and Christological ontology and a corresponding pneumatological epistemology, as expressed through the lives, and especially the prayers, of the saints. This project will follow the structure and rhythm of Balthasar’s Theo-Logic in elaborating the initiatory movement of his account of truth: phenomenological, Christological, and pneumatological. -

Thomas Merton and Zen 143

Thomas Merton and Zen 143 period of years I talked with Buddhists, with and without interpreters, as well as with Christian experts in Buddhist meditation, in Rome, Tokyo, Kyoto, Bangkok, and Seoul. Then, in 1992, I came across a book on Korean Zen. I do not have the patience for soto Zen. And I had dab bled in rinzai Zen, with the generous and kind help of K. T. Kadawoki at Sophia University in Tokyo; but I was a poor pupil, got nowhere, and gave up quickly. Thomas Merton and Zen I found Korean Zen, a form of rinzai, more aggressive; it insists on questioning. Sitting in the Loyola Marymount University library in Los Angeles, reading a book on Korean Zen, I experienced en Robert Faricy lightenment. And it lasted. Later, my library experience was verified independently by two Korean Zen masters as an authentic Zen en lightenment experience. In the book Contemplative Prayer 1 Thomas Merton presents his In the spring of 1993, after several months of teaching as a mature thought on Christian contemplation. The problem is this: visiting professor at Sogang University in Seoul, I went into the moun Merton's last and most important writing on contemplation can be, tains not far inland from Korea's southern coast to a hermitage of the and often is, misunderstood. Contemplative prayer, as described by main monastery of the Chogye order, Songwang-sa, for three weeks of Merton in the book, can appear solipsistic, self-centered, taking the Zen meditation. It was an intensive and profound experience. Among center of oneself as the object of contemplation, taking the same per other things, it brought me back to another reading of Contemplative son contemplating as the subject to be contemplated. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

The Cloud of Unknowing Pdf Free Download

THE CLOUD OF UNKNOWING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anonymous | 138 pages | 20 May 2011 | Aziloth Books | 9781908388131 | English | Rookhope, United Kingdom The Cloud of Unknowing PDF Book He writes in Chapter But again, in this very failure of understanding, in the Dionysian formula, we know by unknowing. A similar image is used in the Cloud line and Book Three, poem 9, of Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy, where the First Mover calls back the souls scattered throughout the universe "like leaping flames" trans. In the end, as The Cloud's author insists: " If you want to find your soul, look at what your love"--and, I would add, at who loves you! Nought occurs also in Chapter Eighteen, lines , as a term derogatorily applied to contemplation by those who do not understand it; and, in Chapter Forty-four, by recommending to the contemplative a sorrow connected with the fact that he simply exists or is line , the author evokes a deeply ontological variation of this "nothing" that suggests the longing of contingency for absolute being. Perhaps my favorite thing about this book, however, is the anonymous writer. The analysis of tempered sensuality, motivated by reflections on the resurrection and ascension, is the author's last treatment of the powers of the soul, knowledge of which keeps the contemplative from being deceived in his effort to understand spiritual language and experience lines In the first mansion of the Temple of God which is the soul, understanding and affectivity operate naturally in the natural sphere, although helped by illuminating grace. Whether we prefer Ignatius' way of images or the image-less way of The Cloud, all prayer is a simple reaching out to God what The Cloud calls ' a naked intent for God' and allowing God to reach back to us. -

The Marian Journal Keeping Members and Friends of the Order of the Most Holy Mary Theotokos Informed

The Marian Journal Keeping members and friends of the Order of the Most Holy Mary Theotokos informed. “The Old Catholic Marianists” February 2015 Volume 6, Number 1 In a sincere desire to share the joyful happiness of our hearts, we present this February 2015 edition of “The Marian Journal”. (The ordination of women to ministerial or priestly office is a regular practice among some major religious groups of the present time, as it was of several religions of antiquity. It remains a controversial issue in certain religions or denominations where the ordination, the process by which a person is consecrated and set apart for the administration of various religious rites, or where the role that an ordained person fulfills, has traditionally been restricted to men. That traditional restriction might have been due to cultural prohibition or theological doctrine, or both. In some cases women have been permitted to be ordained, but not to hold higher positions, such as Bishop. In O.SS.T., we believe that all Holy Orders (bishops, priests, and deacons) are open to both men and women, single or married.) In this Issue: Women’s Ordination Women’s by Ordination Page 1. The Very Reverend Mother Aurore Leigh Barrett, O.SS.T. O.SS.T and The As I read the newspaper accounts of women trying to be ordained as priests, I am struck by the lack of understanding these women seem to have about Aisling Catholicism as a whole. There are many Catholic Jurisdictions that would Community enter welcome women as Ordained Priests, so it makes me question why these women into Agreement of insist that they only be ordained through the Roman Catholic Church. -

Willa Cather's Spirituality

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 7-12-1996 Willa Cather's Spirituality Mary Ellen Scofield Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Scofield, Mary Ellen, "Willa Cather's Spirituality" (1996). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5262. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7135 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Mary Ellen Scofield for the Master of Arts in English were presented July 12, 1996, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: Sherrie Gradin Shelley Reed \ !'aye Powell Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: ********************************************************************* ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY by on 21-<7 ~4?t4Y: /99C:. ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Mary Ellen Scofield for the Master of Arts in English presented July 12, 1996. Title: Willa Cather's Spirituality Both overtly and subtly, the early twentieth century American author Willa Cather (1873-1947) gives her readers a sense of a spiritual realm in the world of her novels. '!'his study explores Cather's changing <;onceptions of spirituality and ways_in which she portrays them in three ~ her novels. I propose that though Cather is seldom considered a modernist, her interest in spirituality parallels Virginia Woolf's interest in moments of heightened consciousness, and that she invented ways to express ineffable connections with a spiritual dimension of life. -

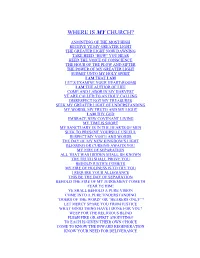

177 WHERE IS MY CHURCH.Pdf

WHERE IS MY CHURCH? ANOINTING OF THE MOST HIGH RECEIVE YE MY GREATER LIGHT THE GREATER LIGHT NOW DAWNING TAKE HEED “HOW” YOU HEAR HEED THE VOICE OF CONSCIENCE THE HOUR OF THE PLOW AND SIFTER THE POWER OF MY GREATER LIGHT SUBMIT UNTO MY HOLY SPIRIT I AM THAT I AM LET’S EXAMINE YOUR HEART-ROOMS I AM THE AUTHOR OF LIFE COME AND LABOR IN MY HARVEST YE ARE CALLED TO AN HOLY CALLING DISRESPECT NOT MY TREASURES SEEK MY GREATER LIGHT OF UNDERSTANDING MY WORDS, MY TRUTH AND MY LIGHT I AM THY GOD EMBRACE NEW COVENANT LIVING MY TIME IS SHORT MY SANCTUARY IS IN THE HEARTS OF MEN SEEK TO PRESENT YOURSELF USEFUL RESPECT MY VOICE AND WORDS THE DAY OF MY NEW KINGDOM’S LIGHT BLESSING OR CURSING AWAITS YOU MY FIRE OF SEPARATION ALL THAT WAS HIDDEN SHALL BE KNOWN THE TRUTH SHALL PROVE YOU BEHOLD JUSTICE COMETH MY FIRE OF HOLINESS IS TO TRY YOU I REQUIRE YOUR ALLEGIANCE THIS BE THE DAY OF SEPARATION BEHOLD THE FIRE OF MY JUDGEMENT COMETH FEAR YE HIM! YE SHALL BEHOLD A PURE VISION COME INTO A PURE UNDERSTANDING “DOERS OF THE WORD” OR “HEARERS ONLY”? LET MERCY SPARE YOU FROM JUSTICE WHAT GOOD THING HAVE I DONE FOR YOU? WEEP FOR THE RELIGIOUS BLIND FLESH FIRE OR SPIRIT ANOINTING? TO EACH IS GIVEN THEIR OWN CHOICE COME TO KNOW THE INWARD REGENERATION KNOW YOUR NEED FOR DELIVERANCE SEEK TO BECOME UNBOUNDED THE AVENUE UNTO REDEMPTION BLESSED ARE THEY... THE FULLNESS OF MY GOSPEL RETURN UNTO ME, O MY PEOPLE THE SEALING OF MY REMNANTS RIGHTEOUS TO BE SAVED IN THE KINGDOM OF GOD THE WORDS OF GOD MY WORD SHALL STAND OVERTURN, OVERTURN, OVERTURN! RIPENING IN INIQUITY -

Spiritual Practice – Centering Prayer

CHRIST CHURCH CHRISTIANA HUNDRED Lent in Youth Ministry LENT 2021: THE WAY www.christchurchde.org/lent Week of 2/17-23: The Way of Lament Spiritual Practice – Centering Prayer The Method of Centering Prayer by Thomas Keating Centering Prayer is a method of silent prayer that prepares us to receive the gift of contemplative prayer, prayer in which we experience God’s presence within us, closer than breathing, closer than thinking, closer than consciousness itself. This method of prayer is both a relationship with God and a discipline to foster that relationship. Centering Prayer is not meant to replace other kinds of prayer. Rather, it adds depth of meaning to all prayer and facilitates the movement from more active modes of prayer—verbal, mental, or affective prayer—into a receptive prayer of resting in God. Centering Prayer emphasizes prayer as a personal relationship with God and as a movement beyond conversation with Christ to communion with Him. The source of Centering Prayer, as in all methods leading to contemplative prayer, is the Indwelling Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The focus of Centering Prayer is the deepening of our relationship with the living Christ. The effects of Centering Prayer are ecclesial, as the prayer tends to build communities of faith and bond the members together in mutual friendship and love. Wisdom Saying of Jesus Centering Prayer is based on the wisdom saying of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount: “When you pray, go to your inner room, close the door and pray to your Father in secret. And your Father, who sees in secret, will reward you” – Matthew 6:6. -

The Complete Cloud of Unknowing Paraclete Giants

THE COMPLETE CLOUD OF UNKNOWING PARACLETE GIANTS About This Series: Each Paraclete Giant presents collected works of one of Christianity’s great- est writers—“giants” of the faith. These essential volumes share the pivotal teachings of leading Christian figures throughout history with today’s theological students and all people seeking spiritual wisdom. Also in this Series… THE COMPLETE FÉNELON Edited with translations by Robert J. Edmonson, cj and Hal M. Helms THE COMPLETE JULIAN OF NORWICH Translation and commentary by Father John-Julian, ojn THE COMPLETE THÉRÈSE OF LISIEUX Edited with translations by Robert J. Edmonson, cj THE COMPLETE MADAME GUYON Edited with translations by the Rev. Nancy C. James, PhD THE COMPLETE IMITATION OF CHRIST Translation and commentary by Father John-Julian, ojn THE COMPLETE FRANCIS OF ASSISI Edited, translated, and introduced by Jon M. Sweeney For more information, visit www.paracletepress.com. PARACLETE GIANTS The C OMPLETE OF OF with The Letter of Privy Counsel Translation and Commentary by Father John-Julian, OJN Paraclete Press BREWSTER, MASSACHUSETTS For John Patrick Hedley Clark, d who best knows The Cloud, and for James Hogg, who has told the rest of the world. 2015 First Printing The Complete Cloud of Unknowing: with The Letter of Privy Counsel Copyright © 2015 by The Order of Julian of Norwich ISBN 978-1-61261-620-9 The Paraclete Press name and logo (dove on cross) are trademarks of Paraclete Press, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The complete Cloud of unknowing : with the Letter of privy counsel / translation and commentary by Father John-Julian, OJN. -

The Deformed Face of Truth in Erasmus, Montaigne and Shakespeare’S the Merchant of Venice’ Author: Sam Hall Source: Exegesis (2013) 1, Pp

Title: ‘The Deformed Face of Truth in Erasmus, Montaigne and Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice’ Author: Sam Hall Source: Exegesis (2013) 1, pp. 21-31 The Deformed Face of Truth in Erasmus, Montaigne and Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice Sam Hall I All humaine thynges are lyke the Silenes or double images of Alcibiades, have two faces much vnlyke and dissemble that outwardly seemed death, yet looking within ye shoulde fynde it lyfe and on the other side what seemed lyfe, to be death: what fayre to be foule what riche, beggarly: what cunnyng, rude: what strong, feeble […] Breifly, the Silenus ones beying vndone and disclosed, ye shall fynde all things [are] tourned into a new semblance [sic] Erasmus1 In The Symposium Alcibiades suggests that Socrates is akin to a ‘Silenus statue’.2 This is because there is an absolute disjunction between the philosopher’s foolish appearance in the world—his notorious ugliness, his incessant infatuations with beautiful young men, his poverty—and the ‘moderation’, ‘strength’ and ‘beauty’3 of his innermost thoughts, which ‘despised all things for which other mortals run their races’.4 These statues, observes Erasmus in his famous adage ‘Sileni Alcibiades’ (1515), were commonly carved in the shape of Bacchus’ tutor Silenus, ‘the court buffoon of the gods of poetry’ (CWE, 34, p. 264). They were ‘small figure[s] of carved wood, so made that they could be divided and opened. […] When they were closed they looked like a caricature of a hideous flute-player, when opened they suddenly displayed a deity’ (CWE, p. -

Church at Home the Liturgy of the Hours Feasts & Solemnities

Church at Home The Liturgy of the Hours Feasts & Solemnities Notre Dame Catholic Parish Denver, Colorado Canticle of Zechariah free to worship him without fear, Luke 1:68-79 holy and righteous in his sight all the days of our life. Blessed be the Lord, the God of Israel; You, my child, shall be called the he has come to his people and set prophet of the Most High, them free. for you will go before the Lord to prepare his way, He has raised up for us a mighty to give his people knowledge of savior, salvation born of the house of his servant by the forgiveness of their sins. David. In the tender compassion of our Through his holy prophets he God, promised of old, the dawn from on high shall that he would save us from our break upon us, enemies, to shine on those who dwell from the hands of all who hate in darkness and the shadow of us. death, and to guide our feet into the He promised to show mercy to way of peace. our fathers and to remember his holy cove- Glory be to the Father, and to the nant. Son, and to the Holy Spirit. As it was in the beginning, is This was the oath he swore to our now, and ever shall be. Amen. father Abraham, to set us free from the hands of (Repeat antiphon) our enemies, Click here to jump back to the Table of Contents, which will allow you to jump to the particular feast or solemnity. -

The Cloud of Unknowing 1 PRAYER to the HOLY SPIRIT (All) I

3/4/2016 The Cloud of Unknowing 1 PRAYER TO THE HOLY SPIRIT (All) I. HISTORICAL CONTEXT (Paul Pham) a. THE AUTHOR OF THE CLOUD OF UNKNOWING? b. WHEN DID THE AUTHOR WRITE THE CLOUD OF UNKNOWING? c. WHAT WAS HAPPENING THEN? d. WHERE DID HE WRITE? e. WHO ARE THE AUDIENCES? II. BRIEF INTRODUCTION (Paul Pham) III. Marie will do part II of the book report (Maria Mendez-Nunez) Come Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of your faithful and kindle in them the fire of your love. Send forth your Spirit and they shall be created. And You shall renew the face of the earth. O, God, who by the light of the Holy Spirit, did instruct the hearts of the faithful, grant that by the same Holy Spirit we may be truly wise and ever enjoy His consolations, Through Christ Our Lord, Amen. The author remain anonymous A reflection of his humility To search the content, sources and authorship of the Cloud of Unknowing might seem a futile exercise. Scholars have been able to figure out a great deal about the author’s historical context, his sources and his spiritual heritage. Several scholars point to his being a priest and a contemplative monk, likely a Carthusian. The Carthusian Order, Also called the Order of St. Bruno, A Roman Catholic religious order of enclosed monastics. Founded by Saint Bruno of Cologne in 1084 Includes both monks and nuns. Has its own Rule, called the Statutes. 3/4/2016 The Cloud of Unknowing 7 Carthusian is derived from the Chartreuse Mountains; Saint Bruno built his first hermitage in the valley of these mountains in the French Alps The motto "The Cross is steady while the world is turning.“3/4/2016 The Cloud of Unknowing 9 This is the picture of St.