Underwater Bay Grasses in the Chesapeake Bay and Rivers in 2010 Page 1 of 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanticoke Currents Summer 2017

Nanticoke June | 2017 currents CONSERVING THE NATUR AL, CULTURAL, AND RECREATIONAL RESOURCES OF THE NANTICOKE RI VER Homeowners Workshops Golden Nanticoke Creek Freaks Workshop Learn about rain gardens, Was there a fungus among The NWA offers educators an rain barrels, pollinator- us? Find out what caused a opportunity to learn about friendly gardening practices, golden sheen on the our local waterways and lawn fertilization, converting Nanticoke in May. learn activities they can lawns to meadows, and conduct with their students See pages 2 & 3 . more. inside and outside. See page 6. See page 5. C+ Grade for the Nanticoke Report Card The Nanticoke’s grades slipped a bit this year. Increased rainfall and higher levels of phosphorus are damaging the waterways. Learn more about the issues and what you can do. See page 7. Unusual Golden Sheen on the Nanticoke River Photo Credit: Tom Darby Written by Mike Pretl & Judith Stribling May 22 dawned as a normal though periodically rainy day for NWA’s Creekwatchers. Every other Monday from late March through early November – rain or shine -- our trained volunteers visit 36 sites on the river and its major tributaries, from Delaware down to Nanticoke. These citizen scientists collect water samples and partner labs analyze for total nitrogen, total phosphorus, chlorophyll a, and bacteria. Creekwatchers also measure dissolved oxygen, salinity, water temperature, water clarity, and total water depth directly. Lastly, Creekwatchers note and record on data sheets the temperature and weather conditions as well as any unusual phenomenon of the water or its surrounding habitat. That morning, our river waters displayed nothing abnormal, only an occasional, slight film of brownish algae, to be expected in the spring months. -

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

Flood Insurance Study

FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY CECIL COUNTY, MARYLAND AND INCORPORATED AREAS Cecil County Community Community Name Number ↓ CECIL COUNTY (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) 240019 *CECILTON, TOWN OF 240020 CHARLESTOWN, TOWN OF 240021 CHESAPEAKE CITY, TOWN OF 240099 ELKTON, TOWN OF 240022 NORTH EAST, TOWN OF 240023 PERRYVILLE, TOWN OF 240024 PORT DEPOSIT, TOWN OF 240025 RISING SUN, TOWN OF 240158 *No Special Flood Hazard Areas Identified Revised: May 4, 2015 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 24015CV000B NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) report may not contain all data available within the Community Map Repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. Part or all of this FIS may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of the FIS may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision (LOMR) process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the user to consult with community officials and to check the community repository to obtain the most current FIS components. Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: July 8, 2013 Revised Countywide FIS Effective Date: May 4, 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. -

Gunpowder River

Table of Contents 1. Polluted Runoff in Baltimore County 2. Map of Baltimore County – Percentage of Hard Surfaces 3. Baltimore County 2014 Polluted Runoff Projects 4. Fact Sheet – Baltimore County has a Problem 5. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Back River 6. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Gunpowder River 7. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Middle River 8. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Patapsco River 9. FAQs – Polluted Runoff and Fees POLLUTED RUNOFF IN BALTIMORE COUNTY Baltimore County contains the headwaters for many of the streams and tributaries feeding into the Patapsco River, one of the major rivers of the Chesapeake Bay. These tributaries include Bodkin Creek, Jones Falls, Gwynns Falls, Patapsco River Lower North Branch, Liberty Reservoir and South Branch Patapsco. Baltimore County is also home to the Gunpowder River, Middle River, and the Back River. Unfortunately, all of these streams and rivers are polluted by nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment and are considered “impaired” by the Maryland Department of the Environment, meaning the water quality is too low to support the water’s intended use. One major contributor to that pollution and impairment is polluted runoff. Polluted runoff contaminates our local rivers and streams and threatens local drinking water. Water running off of roofs, driveways, lawns and parking lots picks up trash, motor oil, grease, excess lawn fertilizers, pesticides, dog waste and other pollutants and washes them into the streams and rivers flowing through our communities. This pollution causes a multitude of problems, including toxic algae blooms, harmful bacteria, extensive dead zones, reduced dissolved oxygen, and unsightly trash clusters. -

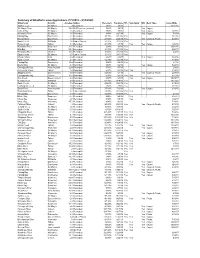

Summary of Lease Applications 9-23-20.Xlsx

Summary of Shellfish Lease Applications (1/1/2015 - 9/23/2020) Waterbody County AcreageStatus Received CompleteTFL Sanctuary WC Gear Type IssuedDate Smith Creek St. Mary's 3 Recorded 1/6/15 1/6/15 11/21/16 St. Marys River St. Mary's 16.2 GISRescreen (revised) 1/6/15 1/6/15 Yes Cages Calvert Bay St. Mary's 2.5Recorded 1/6/15 1/6/15 YesCages 2/28/17 Wicomico River St. Mary's 4.5Recorded 1/8/15 1/27/15 YesCages 5/8/19 Fishing Bay Dorchester 6.1 Recorded 1/12/15 1/12/15 Yes 11/2/15 Honga River Dorchester 14Recorded 2/10/15 2/26/15Yes YesCages & Floats 6/27/18 Smith Creek St Mary's 2.6 Under Protest 2/12/15 2/12/15 Yes Harris Creek Talbot 4.1Recorded 2/19/15 4/7/15 Yes YesCages 4/28/16 Wicomico River Somerset 26.7Recorded 3/3/15 3/3/15Yes 10/20/16 Ellis Bay Wicomico 69.9Recorded 3/19/15 3/19/15Yes 9/20/17 Wicomico River Charles 13.8Recorded 3/30/15 3/30/15Yes 2/4/16 Smith Creek St. Mary's 1.7 Under Protest 3/31/15 3/31/15 Yes Chester River Kent 4.9Recorded 4/6/15 4/9/15 YesCages 8/23/16 Smith Creek St. Mary's 2.1 Recorded 4/23/15 4/23/15 Yes 9/19/16 Fishing Bay Dorchester 12.4Recorded 5/4/15 6/4/15Yes 6/1/16 Breton Bay St. -

Choptank Tributary Summary: a Summary of Trends in Tidal Water Quality and Associated Factors, 1985-2018

Choptank Tributary Summary: A summary of trends in tidal water quality and associated factors, 1985-2018. June 7, 2021 Prepared for the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) Partnership by the CBP Integrated Trends Analysis Team (ITAT) This tributary summary is a living document in draft form and has not gone through a formal peer review process. We are grateful for contributions to the development of these materials from the following individuals: Jeni Keisman, Rebecca Murphy, Olivia Devereux, Jimmy Webber, Qian Zhang, Meghan Petenbrink, Tom Butler, Zhaoying Wei, Jon Harcum, Renee Karrh, Mike Lane, and Elgin Perry. 1 Contents 1. Purpose and Scope .................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Location ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Watershed Physiography .................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Land Use .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Land Use ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.3 Tidal Waters and Stations ................................................................................................................... 8 3. Tidal -

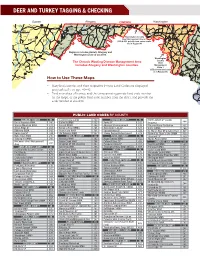

Deer and Turkey Tagging & Checking

DEER AND TURKEY TAGGING & CHECKING Garrett Allegany CWDMA Washington Frederick Carroll Baltimore Harford Lineboro Maryland Line Cardiff Finzel 47 Ellerlise Pen Mar Norrisville 24 Whiteford ysers 669 40 Ringgold Harney Freeland 165 Asher Youghiogheny 40 Ke 40 ALT Piney Groev ALT 68 615 81 11 Emmitsburg 86 ge Grantsville Barrellville 220 Creek Fairview 494 Cearfoss 136 136 Glade River aLke Rid 546 Mt. avSage Flintstone 40 Cascade Sabillasville 624 Prospect 68 ALT 36 itts 231 40 Hancock 57 418 Melrose 439 Harkins Corriganville v Harvey 144 194 Eklo Pylesville 623 E Aleias Bentley Selbysport 40 36 tone Maugansville 550 419410 Silver Run 45 68 Pratt 68 Mills 60 Leitersburg Deep Run Middletown Springs 23 42 68 64 270 496 Millers Shane 646 Zilhman 40 251 Fountain Head Lantz Drybranch 543 230 ALT Exline P 58 62 Prettyboy Friendsville 638 40 o 70 St. aulsP Union Mills Bachman Street t Clear 63 491 Manchester Dublin 40 o Church mithsburg Taneytown Mills Resevoir 1 Aviltn o Eckhart Mines Cumberland Rush m Spring W ilson S Motters 310 165 210 LaVale a Indian 15 97 Rayville 83 440 Frostburg Glarysville 233 c HagerstownChewsville 30 er Springs Cavetown n R 40 70 Huyett Parkton Shawsville Federal r Cre Ady Darlingto iv 219 New Little 250 iv Cedar 76 140 Dee ek R Ridgeley Twiggtown e 68 64 311 Hill Germany 40 Orleans r Pinesburg Keysville Mt. leasP ant Rocks 161 68 Lawn 77 Greenmont 25 Blackhorse 55 White Hall Elder Accident Midlothian Potomac 51 Pumkin Big pringS Thurmont 194 23 Center 56 11 27 Weisburg Jarrettsville 136 495 936 Vale Park Washington -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Summary of Decisions Regarding Nutrient and Sediment Load Allocations and New Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) Restoration Goals

To: Principal Staff Committee Members and Representatives of Chesapeake Bay “Headwater” States From: W. Tayloe Murphy, Jr., Chair Chesapeake Bay Program Principals’ Staff Committee Subject: Summary of Decisions Regarding Nutrient and Sediment Load Allocations and New Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) Restoration Goals For the past twenty years, the Chesapeake Bay partners have been committed to achieving and maintaining water quality conditions necessary to support living resources throughout the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem. In the past month, Chesapeake Bay Program partners (Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Chesapeake Bay Commission) have expanded our efforts by working with the headwater states of Delaware, West Virginia and New York to adopt new cap load allocations for nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment. Using the best scientific information available, Bay Program partners have agreed to allocations that are intended to meet the needs of the plants and animals that call the Chesapeake home. The allocations will serve as a basis for each state’s tributary strategies that, when completed by April 2004, will describe local implementation actions necessary to meet the Chesapeake 2000 nutrient and sediment loading goals by 2010. This memorandum summarizes the important, comprehensive agreements made by Bay watershed partners with regard to cap load allocations for nitrogen, phosphorus and sediments, as well as new baywide and local SAV restoration goals. Nutrient Allocations Excessive nutrients in the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributaries promote undesirable algal growth, and thereby, prohibit light from reaching underwater bay grasses (submerged aquatic vegetation or SAV) and depress the dissolved oxygen levels of the deeper waters of the Bay. -

Multiproxy Evidence of Holocene Climate Variability from Estuarine Sediments, Eastern North America T

PALEOCEANOGRAPHY, VOL. 20, PA4006, doi:10.1029/2005PA001145, 2005 Multiproxy evidence of Holocene climate variability from estuarine sediments, eastern North America T. M. Cronin,1 R. Thunell,2 G. S. Dwyer,3 C. Saenger,1 M. E. Mann,4,5 C. Vann,1 and R. R. Seal II1 Received 14 February 2005; revised 19 May 2005; accepted 8 July 2005; published 19 October 2005. [1] We reconstructed paleoclimate patterns from oxygen and carbon isotope records from the fossil estuarine benthic foraminifera Elphidium and Mg/Ca ratios from the ostracode Loxoconcha from sediment cores from Chesapeake Bay to examine the Holocene evolution of North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)-type climate variability. Precipitation-driven river discharge and regional temperature variability are the primary influences 18 on Chesapeake Bay salinity and water temperature, respectively. We first calibrated modern d Owater to salinity 18 and applied this relationship to calculate trends in paleosalinity from the d Oforam, correcting for changes in water temperature estimated from ostracode Mg/Ca ratios. The results indicate a much drier early Holocene in which mean paleosalinity was 28 ppt in the northern bay, falling 25% to 20 ppt during the late Holocene. Early Holocene Mg/Ca-derived temperatures varied in a relatively narrow range of 13° to 16°C with a mean temperature of 14.2°C and excursions above 16°C; the late Holocene was on average cooler (mean temperature of 12.8°C). In addition to the large contrast between early and late Holocene regional climate conditions, multidecadal (20–40 years) salinity and temperature variability is an inherent part of the region’s climate during both the early and late Holocene, including the Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age. -

2010 Regular Session

Martin O'Malley, Governor Ch. 431 Chapter 431 (House Bill 1472) AN ACT concerning Hunting Wild Waterfowl – Dorchester, St. Mary’s, Somerset, and Wicomico Counties FOR the purpose of altering the location in which a person may hunt wild waterfowl by certain methods in the waters of Dorchester, St. Mary’s, Somerset, and Wicomico counties; decreasing the distance from shore that the Department of Natural Resources prescribes by regulation for the hunting of wild waterfowl by certain methods in the waters of Dorchester, St. Mary’s, Somerset, and Wicomico counties; and generally relating to hunting wild waterfowl in the waters of Dorchester, St. Mary’s, Somerset, and Wicomico counties. BY repealing and reenacting, with amendments, Article – Natural Resources Section 10–604 through 10–606 Annotated Code of Maryland (2007 Replacement Volume and 2009 Supplement) SECTION 1. BE IT ENACTED BY THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF MARYLAND, That the Laws of Maryland read as follows: Article – Natural Resources 10–604. (a) A person may hunt wild waterfowl while standing in water on the natural bottom only in the waters of the Susquehanna Flats, the nontidal waters of the Potomac River, THE WATERS OF TANGIER SOUND, FISHING BAY, MONIE BAY, MANOKIN RIVER, BIG ANNEMESSEX RIVER, POCOMOKE SOUND, AND KEDGES STRAITS IN THE WATERS OF DORCHESTER, SOMERSET, AND WICOMICO COUNTIES, and in other waters of the State in areas and on days the Department prescribes by regulation. (b) A person may hunt wild waterfowl while standing in water on the natural bottom at a licensed offshore stationary blind or blind site. (c) A person hunting wild waterfowl while standing in water on the natural bottom shall remain at least 250 yards from all offshore stationary blinds or blind sites or another person hunting wild waterfowl offshore. -

Shorerivers-Advocate-Spring-2020

ShoreRivers Advocate CHESTER RIVER | CHOPTANK RIVER MILES & WYE RIVERS | SASSAFRAS RIVER SPRING 2020 Combatting climate change Improving Farm Resiliency through Soil Health & Water Management ShoreRivers Supports LOCAL GREEN SCHOOLS 2019 Donor Appreciation and more… LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR The cover of this edition of the Advocate newsletter footprint, build resiliency into our natural systems, and presents an iconic image of the impacts of climate plan for the future. change on the Eastern Shore. Unfortunately, as you’ll Advocacy: We are promoting legislation to require all discover in the following articles, it is neither a rare development in flood-prone areas to take climate change occurrence, nor is it the only type of impact we are impacts into account. We are recommending regulatory experiencing. The ecological effects on our region of a changes to address increased pollution from construction changing climate include drowned forests, higher tides, site runoff associated with increasingly stronger storms. salty farm fields, and fresher water flowing in our brackish rivers. This translates into Restoration: Restoring our climate crisis: costly the landscape to its infrastructure fixes, natural form protects our canceled events and loss of communities, stores carbon tourism, lower home values, from the atmosphere, flooded main streets, more and builds resiliency in polluted rivers, dangerous the face of a changing swimming conditions, loss future. ShoreRivers excels of productive farmland, and in projects including I could go on. The fact is, a wetland and stream changing climate with restoration, innovative higher temperatures, water management on stronger and more farmland, streamside buffer intense storms, and rising installation, and planting seas increases pollution in our rivers.