The Laureate, 10Th Edition (2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide Represents the Most Requested Songs at Weddings and Parties

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide represents the most requested songs at Weddings and Parties. Please circle songs you like and cross out the ones you don’t. You can also write-in additional requests on the back page! WEDDING SONGS ALL TIME PARTY FAVORITES CEREMONY MUSIC CELEBRATION THE TWIST HERE COMES THE BRIDE WE’RE HAVIN’ A PARTY SHOUT GOOD FEELIN’ HOLIDAY THE WEDDING MARCH IN THE MOOD YMCA FATHER OF THE BRIDE OLD TIME ROCK N ROLL BACK IN TIME INTRODUCTION MUSIC IT TAKES TWO STAYIN ALIVE ST. ELMOS FIRE, A NIGHT TO REMEMBER, RUNAROUND SUE MEN IN BLACK WHAT I LIKE ABOUT YOU RAPPERS DELIGHT GET READY FOR THIS, HERE COMES THE BRIDE BROWN EYED GIRL MAMBO #5 (DISCO VERSION), ROCKY THEME, LOVE & GETTIN’ JIGGY WITH IT LIVIN, LA VIDA LOCA MARRIAGE, JEFFERSONS THEME, BANG BANG EVERYBODY DANCE NOW WE LIKE TO PARTY OH WHAT A NIGHT HOT IN HERE BRIDE WITH FATHER DADDY’S LITTLE GIRL, I LOVED HER FIRST, DADDY’S HANDS, FATHER’S EYES, BUTTERFLY GROUP DANCES KISSES, HAVE I TOLD YOU LATELY, HERO, I’LL ALWAYS LOVE YOU, IF I COULD WRITE A SONG, CHICKEN DANCE ALLEY CAT CONGA LINE ELECTRIC SLIDE MORE, ONE IN A MILLION, THROUGH THE HANDS UP HOKEY POKEY YEARS, TIME IN A BOTTLE, UNFORGETTABLE, NEW YORK NEW YORK WALTZ WIND BENEATH MY WINGS, YOU LIGHT UP MY TANGO YMCA LIFE, YOU’RE THE INSPIRATION LINDY MAMBO #5BAD GROOM WITH MOTHER CUPID SHUFFLE STROLL YOU RAISE ME UP, TIMES OF MY LIFE, SPECIAL DOLLAR WINE DANCE MACERENA ANGEL, HOLDING BACK THE YEARS, YOU AND CHA CHA SLIDE COTTON EYED JOE ME AGAINST THE WORLD, CLOSE TO YOU, MR. -

Music Games Rock: Rhythm Gaming's Greatest Hits of All Time

“Cementing gaming’s role in music’s evolution, Steinberg has done pop culture a laudable service.” – Nick Catucci, Rolling Stone RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME By SCOTT STEINBERG Author of Get Rich Playing Games Feat. Martin Mathers and Nadia Oxford Foreword By ALEX RIGOPULOS Co-Creator, Guitar Hero and Rock Band Praise for Music Games Rock “Hits all the right notes—and some you don’t expect. A great account of the music game story so far!” – Mike Snider, Entertainment Reporter, USA Today “An exhaustive compendia. Chocked full of fascinating detail...” – Alex Pham, Technology Reporter, Los Angeles Times “It’ll make you want to celebrate by trashing a gaming unit the way Pete Townshend destroys a guitar.” –Jason Pettigrew, Editor-in-Chief, ALTERNATIVE PRESS “I’ve never seen such a well-collected reference... it serves an important role in letting readers consider all sides of the music and rhythm game debate.” –Masaya Matsuura, Creator, PaRappa the Rapper “A must read for the game-obsessed...” –Jermaine Hall, Editor-in-Chief, VIBE MUSIC GAMES ROCK RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME SCOTT STEINBERG DEDICATION MUSIC GAMES ROCK: RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME All Rights Reserved © 2011 by Scott Steinberg “Behind the Music: The Making of Sex ‘N Drugs ‘N Rock ‘N Roll” © 2009 Jon Hare No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. -

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © the Poisoned Pen, Ltd

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © The Poisoned Pen, Ltd. 4014 N. Goldwater Blvd. Volume 33, Number 9 Scottsdale, AZ 85251 June Booknews 2021 480-947-2974 [email protected] tel (888)560-9919 http://poisonedpen.com THERE IS MUCH TO CELEBRATE IN JUNE Opening Hours M-Sat 10 AM-6 PM; Sun 12-5 PM Note: All the event times are Pacific Daylight time Watch these virtual events on Facebook Live or on our YouTube channel and any time thereafter at a time that suits you. You don’t have to belong to Facebook to click in. You also can listen to our Podcasts on Google Music, iTunes, Spotify, and other popular podcast sites. TUESDAY JUNE 1 7:00 PM National Book Launch MONDAY JUNE 14 5:00 PM Antiques Mysteries JA Jance discusses Unfinished Business (Gallery $27.99) Connie Berry in conversation with Jane Cleland Sedona’s Ali Reynolds Berry discusses The Art of Betrayal (Crooked Lane $26.99) Signed book available Signed books available for Berry WEDNESDAY JUNE 2 6:00 PM TUESDAY JUNE 15 12:00 PM Michael Punke in conversation with CJ Box Sir Roderick Floud discusses England’s Magnificent Gardens Punke discusses Ridgeline (Holt $27.99) (Knopf $40) A novel of the western frontier 1866 An economic historian looks at a billion dollar industry from Signed books available Charles II to today SATURDAY JUNE 5 4:00 PM National Book Launch WEDNESDAY JUNE 16 5:00 PM Laurie R. King discusses Castle Shade (Random $28) John McMahon and David Ricciardi Russell & Holmes in Romania McMahon discusses A Good Kill (Putnam $27 Signed books available Ricciardi discusses Shadow -

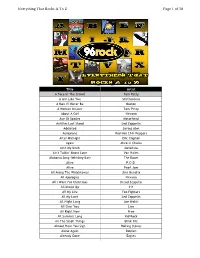

Of 30 Everything That Rocks a to Z

Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 1 of 30 Title Artist A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty A Girl Like You Smithereens A Man I'll Never Be Boston A Woman In Love Tom Petty About A Girl Nirvana Ace Of Spades Motorhead Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Addicted Saving Abel Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers After Midnight Eric Clapton Again Alice In Chains Ain't My Bitch Metallica Ain't Talkin' About Love Van Halen Alabama Song (Whiskey Bar) The Doors Alive P.O.D. Alive Pearl Jam All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All Apologies Nirvana All I Want For Christmas Dread Zeppelin All Mixed Up 311 All My Life Foo Fighters All My Love Led Zeppelin All Night Long Joe Walsh All Over You Live All Right Now Free All Summer Long Kid Rock All The Small Things Blink 182 Almost Hear You Sigh Rolling Stones Alone Again Dokken Already Gone Eagles Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 2 of 30 Always Saliva American Bad Ass Kid Rock American Girl Tom Petty American Idiot Green Day American Woman Lenny Kravitz Amsterdam Van Halen And Fools Shine On Brother Cane And Justice For All Metallica And The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen Angel Aerosmith Angel Of Harlem U2 Angie Rolling Stones Angry Chair Alice In Chains Animal Def Leppard Animal Pearl Jam Animal I Have Become Three Days Grace Animals Nickelback Another Brick In The Wall Pt. 2 Pink Floyd Another One Bites The Dust Queen Another Tricky Day The Who Anything Goes AC/DC Aqualung Jethro Tull Are You Experienced? Jimi Hendrix Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz Armageddon It Def Leppard Around -

Buy Cialis Without Rx

Larry Lay’s Play List Allman Brothers James Blunt Christopher Cross Fuel Billy Joel Ramblin’ Man You’re Beautiful Sailing Hemorrhage (In My Hands) Allentown Always a Woman Louis Armstrong Bush John Denver Peter Gabriel And So It Goes What a Wonderful World Come Down Annie’s Song Solsbury Hill Big Shot Glycerine Country Roads Captain Jack Beatles Rocky Mountain High Goo Goo Dolls Downeaster Alexa And I Love Her Harry Chapin Sunshine on my Shoulders Iris Goodnight Saigon Don’t Let Me Down Cats in the Cradle Honesty Eleanor Rigby Bobby Darin Grateful Dead Just the Way You Are In My Life Ray Charles Beyond the Sea Casey Jones N. Y. State of Mind Lady Madonna Georgia Mack the Knife Friend of the Devil Only the Good Die Young Let It Be What I’d Say Truckin’ Prelude/Angry Young Man Norwegian Wood Stealer’s Wheel Scenes from an Italian Rest. Ohbladee Ohblada Eric Clapton Stuck in the Middle w/ You Green Day Shameless Rocky Raccoon Lay Down Sally Basket Case She’s Got a Way Revolution Tears In Heaven Neil Diamond The Time of Your Life Summer Highland Falls She Came In Thru the Wonderful Tonight Forever in Blue Jeans When I Come Around Vienna Bathroom Window Sweet Caroline Something Marc Cohn Lee Greenwood Elton John With a Little Help From True Companion Dion God Bless the U.S.A. Candle In the Wind My Friends Walkin’ in Memphis Runaround Sue Crocodile Rock Yesterday The Wanderer David Grey Daniel Coldplay Babylon Funeral for a Friend/ Ben Folds Five Clocks Fats Domino Sail Away Love Lies Bleeding Brick Yellow Blueberry Hill Goodbye Yellow Brick Road Kate I’m Walkin’ Hall & Oats Levon Song for the Dumped Nat King Cole Rich Girl Rocket Man Unforgettable Bob Dylan Sara Smile Someone Saved My Life Better Than Ezra Like a Rolling Stone T’nite Good Commodores/ Mr. -

Mike's Acoustic Songlist

2 Pac California Love 3 Doors Down Here Without You Kryptonite Let Me Go Loser 30s Don't Sit Under the Apple Tree Let Me Call You Sweetheart Old Cape Cod Pistol Packin Mama Take Me Out to the Ball Game 311 All Mixed Up Amber Do You Right Flowing I'll Be Here Awhile Love Song 38 Special Caught Up in You Hold on Loosely 4 Non Blondes What's Up Adele Rolling in the Deep Set Fire to the Rain Aerosmith Living on the Edge Rag Doll Sweet Emotion What It Takes Aha Take on Me Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's 5 O'clock Somewhere Alan Parsons Project Eye in the Sky Alanis Morrisette You Oughta Know Alice In Chains Down Man in the Box No Excuses Nutshell Rooster Allman Bros Melissa Ramblin Man Midnight Rider America Horse with no Name Sandman Sister Golden Hair Tin Man American Authors Best Day of My Life Amy Winehouse Valerie Andy Grammer Fine By Me Honey I'm Good Keep Your Head Up Andy Williams Godfather Theme Annie Lennox Here Comes the Rain Arlo Guthrie City of New Orleans Audioslave Like a Stone Avril Lavigne I'm With You Bachman Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Backstreet Boys As Long As You Love Me I Want It That Way Bad Company Ready For Love Shooting Star Badfinger No Matter What Band The Weight Baltimora Tarzan Boy Barefoot Truth Changes in the Weather Barenaked Ladies 1,000,000 Dollars Brian Wilson Call and Answer Old Apartment What a Good Boy Barry Manilow Mandy Barry White Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Beach Boys Fun, Fun, Fun Beatles Eleanor Rigby Fool on the Hill Hard Day's Night Here Comes the Sun Hey Jude Hide Your Love Away I Saw Her Standing There I Wanna Hold Your Hand I'll Follow the Sun Julia Let it Be Norweigan Wood Obladi Oblada She Came Into the Bathroom Things We Said Today Ticket to Ride We Can Work It Out When I'm Sixty-Four With a Little Help From My Friends Bee Gees Jive Talkin Islands in the Stream Massachusetts Nights on Broadway Stayin Alive To Love Somebody Tragedy Bellamy Bros. -

Sean Mormelo Ultimate Cover List

Sean Mormelo Ultimate Cover Band Songlist AC/DC BOB DYLAN COUNTING CROWES HAERTACHE TONIGHT HIGHWAY TO HELL A SIMPLE TWIST OF FATE MR JONES 7 BRIDGES ROAD YOU SHOOK ME ALL KNOCKING ON HEAVENS CREED EDWIN McCAIN NIGHT LONG ITʼS ALL OVER NOW HIGHER IʼLL BE ALANIS MORISSETTE BABY BLUE CREEDENCE ELTON JOHN IRONIC JUST LIKE A WOMAN CLEARWATER BENNIE AND THE JETS ALICE IN CHAINS LAY LADY LAY BAD MOON RISING CANDLE IN THE WIND NO EXCUSES LIKE A ROLLING STONE PROUD MARY CROCODILE ROCK MAN IN THE BOX MASTERS OF WAR DOWN ON THE CORNER DANIEL ALLMAN BROTHERS MIGHTY QUINN HAVE U EVER SEEN THE DONʼT LET THE SUN MELISSA POSITIVELY 4TH ST. RAIN HONKEY CAT RAMBLIN MAN SHELTER FROM THE WHOʼLL STOP THE RAIN LEVON ONE WAY OUT STORM CROSBY STILLS NASH ROCKET MAN AMERICA TANGLED UP IN BLUE SOUTHERN CROSS YOUR SONG HORSE WITH NO NAME YOUʼRE A BIG GIRL NOW LOVE THE ONE YOUʼRE SAT. NIGHTʼS ALRIGHT SISTER GOLDENHAIR BOB SEGER WITH ELVIS BARE NAKED LADIES AGAINST THE WIND DAVE MATTHEWS ALL SHOOK UP THE OLD APARTMENT MAIN STREET ANTS MARCHING BLUE SUEDE SHOES BRAIN WILSON NIGHT MOVES CRASH HOUND DOG BAD COMPANY SUNSPOT BABY STAY JAILHOUSE ROCK CANʼT GET ENOUGH OLʼ TIME ROCK-N-ROLL WHAT WOULD YOU SAY LITTLE SISTER SHOOTING STAR TURN THE PAGE DAN FOGLEBERG THATʼS ALRIGHT MAMA THE BAND YOUʼLL ACCOMPANY ME LEADER OF THE BAND ERIC CLAPTON CRIPPLE CREEK BOB MARLEY DAVE LOGGINS BELL BOTTOM BLUES THE NIGHT THEY DROVE NO WOMAN NO CRY PLEASE COME TO CHANGE THE WORLD OL DIXIE REDEMPTION SONG BOSTON LAY DOWN SALLY THE WEIGHT BON JOVI DAVID GRAY LAYLA THE BEATLES WANTED DEAD -

Berlin Guide, Summer 2011

Berlin: “Is this real life?” the ultimate guide With our sincerest thanks to Marcus, Alex, Caroline, Sofia, Nina, Matt, Lutz and Jeremy. Tours..........8 CONTENTS Food..........9 Nightlife..........10 Shopping...........11 Outdoors..........12 Introduction..........1 Contributors..........13 German..........2 Suriving Berlin..........4 CONTENTS Transport..........3 History.........4 Galleries........5 Introduction 1 Museums...........6 Sites.........7 Good to know 2 Language 4 Transport 6 History 10 Galleries 14 Museums 22 Sights 28 Tours 32 Food and Drink 42 Coffee and Cake 50 Street food 56 Nightlife 60 Shopping 70 Second Hand 74 Markets 76 Outdoors 78 Contributors 86 2 Berlin: “Is this real life?” 3 Artistic talent can also be seen in the city’s architecture such as the WILLKOMMEN IN BERLIN... emblematic Reichstag. This building features the glass dome designed by Norman Foster. Upon arrival the very question of “Is this real life?” may pop into your head. It Other lesser known buildings from the GDR era have been converted into may be after your first time seeing someone face down on a park bench with distinctive night clubs. Whether a historical outing or a night on the town, a Pilsner beer in hand, or perhaps it will be after you read a German menu for visitors are sure to get a taste of the old and the new. the first time and attempt to order your food. Nevertheless, the culture shock A guide to Berlin would be incomplete without mentioning the vast array is one to note. of food the city has to offer. From traditional spätzle noodles to the more The city of Berlin is known for its unique and anti-corporate economy with prominent kebab, all taste buds are catered for, even on the strictest of budg- independently created lifestyles. -

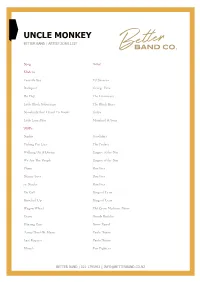

Uncle Monkey Better Band | Artist Song List

UNCLE MONKEY BETTER BAND | ARTIST SONG LIST Song Artist Modern Tenerife Sea Ed Sheeran Budapest George Ezra Ho Hey The Lumineers Little Black Submarine The Black Keys Somebody that I Used To Know Gotye Little Lion Man Mumford & Sons 2000's Sophie Goodshirt Fishing For Lisa The Feelers Walking On A Dream Empire of the Sun We Are The People Empire of the Sun Flume Bon Iver Skinny Love Bon Iver re: Stacks Bon Iver On Call Kings of Leon Knocked Up Kings of Leon Wagon Wheel Old Crow Medicine Show Crazy Gnarls Barkley Chasing Cars Snow Patrol Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini Miracle Foo Fighters BETTER BAND | 021 1795953 | [email protected] Love Generation Bob Sinclar A Place For You Breaks Co Op Leaders of the Free World Elbow An Imagined Affair Elbow Dakota Stereophonics What If I Do Foo Fighters So Long, Jimmy James Blunt Won't Give In The Finn Brothers Fugitive Motel Elbow Times Like These Foo Fighters Hey Ya! Outkast So Beautiful Pete Murray Gone For Good The Shins Turn A Square The Shins In My Place Coldplay No One Knows Queens Of The Stone Age Don't Panic Coldplay Side Travis Island In The Sun Weezer Steal My Kisses Ben Harper Yellow Coldplay My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Bohemian Like You The Dandy Warhols 90's Sail Away David Gray We Haven't Turned Around Gomez Californication Red Hot Chilli Peppers Otherside Red Hot Chilli Peppers BETTER BAND | 021 1795953 | [email protected] Why Does It Always Rain On Me Travis Dance The Night Away The Mavericks Everlong Foo Fighters Brimful -

March 2, 1998

The student newspaper of Glenville State College - Cheap at Twice the Price! TAKE ONE! trrur, Music Student Day..• Page 6 "Men, .real men, don't feel this blatant need to make themselves feel macho by putting others down. " ........................... PageIO-l1 •••••••••••••••••••••. Page 13 _'LOaD News ............... Page 2 ........................ Page4-S •••••••••••••••••• Page 12 possible end . of the world -- Page 13 Hal' to the Chlefl January jobless ood plans rate rises to 7.5% CHARLESTON West Vuginia's unemploy rail workshops mCDt rate rose 1 percentage Clildren sbouId look poiDt to 7.S percent in udwmMU~mM•• ~_" ; CHAItLSSTON, w.Va. - cess of the plan,.. he said. January, the steepest climb in in bJICk bisby &'II roll"'•• ,. ~ ....... in die works Kent SpeUman, chairman a year, due to ~ross4he iDSIaId of....... ",•• ;::..-_t~ ~ West Vqiaia have of the statewide trail plan com board winter slow4owns, as, ICmem Abdul- .illiill,":'!!'1i Ibe poIIIdiaI to pump milUoas of mittee, said an economic-impact according to the state Bureau Jabbar told a group .....i ... doIIIn iato ecoaomies, .. DOW study of the proposed North of Bmployment Propams. of coDege studeaIs. ia Ibe time for .....u businesses Bend Rail Trail in Ritchie The rate was the high SpeakiDg ....IIL... to pi involved, Gov. Cecil County showed it could gener est since April 1997 but was Monday at \\at Underwood said. ate about $4.9 million for the the lowest for any January Vuginia University, PIIImina wubbops for a economy of West Union and the since 1979, the agencY said. the fanner NBA ... IIIIIIewide syIIIIn of 1rBiIs will be surrounding area. -

Incidentally

i mm m PAGE 10 THE RETRIEVER FEATURES NOVEMBER 2, 1993 The Clampetts Should Ve Pearl Jam is Back. As Grungy As Ever Tom Miley Stayed In TV-Land Retriever Staff Writer From HILLBILLIES, Page 9 The level of acting matches the of reach. So, I was hoping to see As you may or may not know, ally and adapt the Clampett's val- films high comic standards. Each Rodeo Drive, the galleries, and Pearl Jam's back! Now I know you ues—to the point where Hathaway Clampett can be summed up in a nightclubs. But this film relies on may be thinking that they're hopping takes a shotgun to a computer and single word: Jed is fatherly, Elly May cheap studio sets. I bet they spent on the bandwagon (after all, Nirvana shatters it with buckshot. is tomboyish, Granny is ornery and a pretty penny on set design. did just release another album). So Oh, did I forget to mention the Jethro is stupid. The actors are more I must concede that the movie let me say this, in my opinion, Pearl plot? Well, hey, so did the movie. The concerned with their physical resem- does have a few funny moments, Jam's second release is as good if not threadbare story concerns Jed's blance to the characters than their especially a chance of syllable better than Nirvana's "In Utero." The search for a^wife. Lea Thompson, as development of distinct personalities. stress on the word "happiness" new album, titled "Vs.," is full of the a perfidious pilferer, plots to marry They don't act, they impersonate. -

Song List 2014

Dave Matthews Songs: Other Songs: Summer of 69’ - Bryan Adams Best of What’s Around Toes - Zac Brown Band War Pigs - Black Sabbath What Would You Say Chicken Fried - Zac Brown Band Rooster - Alice in Chains (AIC) Satellite Ecstasy - Rusted Root Down In a Hole - AIC Jimi Thing Send Me On My Way - Rusted Root Got Me Wrong - AIC Dancing Nancies Laid - James Don’t Follow - AIC Ants Marching Stuck In The Middle - Steelers Wheel Old Blue Chair - Kenny Chesney Warehouse Taylor - Jack Johnson Friends In Low Places - G Brooks Typical Situation Posters - Jack Johnson Fade to Black - Metallica Lover Lay Down Why Georgia - John Mayer All These Things I’ve Done - Killers One - U2 Use Somebody - ! Kings of Leon So Much To Say With Or Without You - U2 Little Lion Man - Mumford & Sons Too Much All I Want Is You - U2 I Will Wait - Mumford & Sons #41 Free Fallin - Tom Petty Crash Wild Flowers - Tom Petty Lie In Our Graves Wanted Dead Or Alive - Bon Jovi Two Step Home - Phillip Phillips Say Goodbye Me & Julio - Paul Simon Drive In Drive Out Homeward Bound - Paul Simon Tripping Billies Blackbird - Beatles We Can Work It Out - Beatles Rapunzel Franklin’s Tower - Grateful Dead Don’t Drink The Water Ripple - Grateful Dead Stay What I Got - Sublime Crush Sweet Home Alabama - Skynard The Last Stop Santeria - Sublime The Stone Creep - Radiohead Pig Fake Plastic Trees - Radiohead Dreaming Tree Margaritaville - Jimmy Buffett Get Drunk & Screw - Jimmy Buffett Everyday Viva La Vida - Coldplay Bartender Clocks - Coldplay Where Are You Going Green Eyes - Coldplay Grey Street The Scientist - Coldplay Grace Is Gone Waste - Phish Stand Up Redemption Song - Bob Marley The Space Between Elderly Woman..