The Queen, Aging Femininity and the Recuperation of the Monarchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Dis)Believing and Belonging: Investigating the Narratives of Young British Atheists1

(Dis)Believing and Belonging: Investigating the Narratives of Young British Atheists1 REBECCA CATTO Coventry University JANET ECCLES Independent Researcher Abstract The development and public prominence of the ‘New Atheism’ in the West, particularly the UK and USA, since the millennium has occasioned considerable growth in the study of ‘non-religion and secularity’. Such work is uncovering the variety and complexity of associated categories, different public figures, arguments and organi- zations involved. There has been a concomitant increase in research on youth and religion. As yet, however, little is known about young people who self-identify as atheist, though the statistics indicate that in Britain they are the cohort most likely to select ‘No religion’ in surveys. This article addresses this gap with presentation of data gathered with young British people who describe themselves as atheists. Atheism is a multifaceted identity for these young people developed over time and through experience. Disbelief in God and other non-empirical propositions such as in an afterlife and the efficacy of homeopathy and belief in progress through science, equality and freedom are central to their narratives. Hence belief is taken as central to the sociological study of atheism, but understood as formed and performed in relationships in which emotions play a key role. In the late modern context of contemporary Britain, these young people are far from amoral individualists. We employ current theorizing about the sacred to help understand respondents’ belief and value-oriented non-religious identities in context. Keywords: Atheism, Youth, UK, Belief, Sacred Phil Zuckerman (2010b, vii) notes that for decades British sociologist Colin Campbell’s call for a widespread analysis of irreligion went largely un- heeded (Campbell 1971). -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Princess Diana, the Musical Inspired by Her True Story

PRINCESS DIANA, THE MUSICAL INSPIRED BY HER TRUE STORY Book by Karen Sokolof Javitch and Elaine Jabenis Music and Lyrics by Karen Sokolof Javitch Copyright © MMVI All Rights Reserved Heuer Publishing LLC, Cedar Rapids, Iowa Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that this work is subject to a royalty. Royalty must be paid every time a play is performed whether or not it is presented for profit and whether or not admission is charged. A play is performed any time it is acted before an audience. All rights to this work of any kind including but not limited to professional and amateur stage performing rights are controlled exclusively by Heuer Publishing LLC. Inquiries concerning rights should be addressed to Heuer Publishing LLC. This work is fully protected by copyright. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission of the publisher. Copying (by any means) or performing a copyrighted work without permission constitutes an infringement of copyright. All organizations receiving permission to produce this work agree to give the author(s) credit in any and all advertisement and publicity relating to the production. The author(s) billing must appear below the title and be at least 50% as large as the title of the Work. All programs, advertisements, and other printed material distributed or published in connection with production of the work must include the following notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Heuer Publishing LLC of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.” There shall be no deletions, alterations, or changes of any kind made to the work, including the changing of character gender, the cutting of dialogue, or the alteration of objectionable language unless directly authorized by the publisher or otherwise allowed in the work’s “Production Notes.” The title of the play shall not be altered. -

Conquering the Colon: the Adventure of Advanced Punctuation

Oregon State Bar Bulletin — APRIL 2010 April Issue The Legal Writer Conquering the Colon: The Adventures of Advanced Punctuation By Suzanne E. Rowe Perhaps the only punctuation mark more terrifying than the semicolon is the colon. Most writers avoid the colon for fear of misusing it. Most readers feel intimidated by the brave writer who dared try to master the colon’s nuances. When is a colon appropriate? How many spaces follow it? Does the word after a colon need to be capitalized? This article will bring you closer to conquering your fear of the colon. When to Use a Colon Colon usage varies from the exciting to the mundane. In the first two explanations below, think of the colon as the pause — or the drum roll — between an introduction and the exciting details. Picture someone on stage with an envelope saying, “And the winner is…!” The remaining explanations are more mundane, but perhaps easier. Lists One common use of a colon is to introduce a list. The nominees for best actress were impressive: Sandra Bullock, Helen Mirren, Carey Mulligan, Gabourey Sidibe and Meryl Streep. Be sure that the introductory sentence preceding the colon is truly a sentence. A colon would be incorrect in the following example. The nominees were Sandra Bullock, Helen Mirren, Carey Mulligan, Gabourey Sidibe and Meryl Streep. Independent clauses In the use that inspires the most fear, a colon separates two independent clauses when the second clause expands or illustrates the idea in the first clause. (Remember that an independent clause is just a complete sentence.) The drum roll — the colon — comes after the first sentence. -

Spring 2011 Issn 1476-6760

Issue 65 Spring 2011 Issn 1476-6760 Christine Hallett on Historical Perspectives on Nineteenth-Century Nursing Karen Nolte on the Relationship between Doctors and Nurses in Agnes Karll’s Letters Dian L. Baker, May Ying Ly, and Colleen Marie Pauza on Hmong Nurses in Laos during America’s Secret War, 1954- 1974 Elisabetta Babini on the Cinematic Representation of British Nurses in Biopics Anja Peters on Nanna Conti – the Nazis’ Reichshebammenführerin Lesley A. Hall on finding female healthcare workers in the archives Plus Four book reviews Committee news www.womenshistorynetwork.org 9 – 11 September 2011 20 Years of the Women’s History Network Looking Back - Looking Forward The Women’s Library, London Metropolitan University Keynote Speakers: Kathryn Gleadle, Caroline Bressey Sheila Rowbotham, Sally Alexander, Anna Davin Krista Cowman, Jane Rendall, Helen Meller The conference will look at the past 20 years of writing women’s history, asking the question where are we now? We will be looking at histories of feminism, work in progress, current areas of debate such as religion and perspectives on national and international histories of the women’s movement. The conference will also invite users of The Women’s Library to take part in one strand that will be set in the Reading Room. We would very much like you to choose an object/item, which has inspired your writing and thinking, and share your experience. Conference website: www.londonmet.ac.uk/thewomenslibrary/ aboutthecollections/research/womens-history-network-conference-2011.cfm Further information and a conference call will be posted on the WHN website www.womenshistorynetwork.org Editorial elcome to the spring issue of Women’s History This issue, as usual, also contains a collection of WMagazine. -

The Life and Death of an Icon Facil Ute Core Core Tie Modiam, Conulla

WW | xxxxxxxx THIS STORY ALWAYS HAD everything, didn’t it? The blushing young innocent who transformed herself into the most adored – and most hunted – woman in the world. The Cinderella who found her Prince Charming – or thought she did – and then entered the palace via the golden carriage. The fairytale but fraudulent wedding of the century, followed by that grim parable of death in the Paris tunnel. The romance, the adultery, the royal intrigue, the eternal, hopeless quest for love, the media’s crazed preoccupation and pursuit. TIn her lifetime, Diana was the People’s Princess who, in death, became the Sleeping Beauty and the Lady of the Lake. She was the stuff that myths are made of and, like her or not, believe it or not, hers was a tale of epic, monumental proportions, that mesmerised the world for 16 years – from the time she walked down the aisle in St Paul’s Cathedral to the time of her funeral in Westiminster Abbey, witnessed by, what was it, a quarter of the world’s population? permafrost and the duke’s Teutonic coldness Think of Marilyn Monroe, Princess Grace, to Diana’s single-minded pursuit of Prince Greta Garbo, Jackie Onassis, perhaps even Charles and her elder son, William’s, interest Mother Theresa, and roll them into one in becoming governor-general of Australia. iconic figure, and you might approach the The Diana Spencer that emerges from fame, the celebrity of Diana Spencer, the pages of Tina Brown’s The Diana Celebrated editor Tina Princess of Wales. As Martin Amis, the Chronicles is at once childish, scheming, Brown’s sensational new writer, once said, “Madonna sings. -

From Baking Bread to Making Dough: Legal and Societal Restrictions on the Employment of First Ladies Sara Krausert

The University of Chicago Law School Roundtable Volume 5 | Issue 1 Article 9 1-1-1998 From Baking Bread to Making Dough: Legal and Societal Restrictions on the Employment of First Ladies Sara Krausert Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/roundtable Recommended Citation Krausert, Sara (1998) "From Baking Bread to Making Dough: Legal and Societal Restrictions on the Employment of First Ladies," The University of Chicago Law School Roundtable: Vol. 5: Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/roundtable/vol5/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in The nivU ersity of Chicago Law School Roundtable by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS From Baking Bread to Making Dough: Legal and Societal Restrictions on the Employment of First Ladies SARA KRAUSERT t The paradigmatic First Lady' embodies the traditional role played by women in the United States. Since the position's creation, both Presidents and the public have wanted First Ladies to be seen and not heard. Some First Ladies have stayed within these confines, either by doing no more than simply supporting their husbands, or by taking care to exercise power only behind the scenes. Several First Ladies in this century, however have followed the lead of Eleanor Roosevelt, who broke barriers in her vigorous campaigns for various social causes, and they have brought many worthy issues to the forefront of the American consciousness.' Most recently, with the rumblings of discontent with the role's limited opportunities for independent action that accompanied the arrival of the women's movement, Rosalynn Carter and Hillary Clinton attempted to expand the role of the First Lady even further by becoming policy-makers during their husbands' presidencies.3 This evolution in the office of First Lady parallels women's general progress in society. -

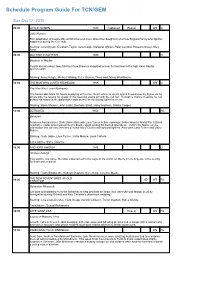

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GEM Sun Oct 17, 2010 06:00 LITTLE WOMEN 1949 Captioned Repeat WS G Little Women Film adaptation of Louisa May Alcott's beloved novel about four daughters of a New England family who fight for happiness during the Civil War. Starring: June Allyson, Elizabeth Taylor, Janet Leigh, Margaret O'brien, Peter Lawford, Rossano Brazzi, Mary Astor 08:30 MAYTIME IN MAYFAIR 1949 G Maytime In Mayfair Penniless man-about-town Michael Gore-Brown is delighted to hear he has been left a high-class Mayfair fashion salon. Starring: Anna Neagle, Michael Wilding, Peter Graves, Thora Hird, Mona Washbourne 10:35 THE MAN WHO LOVED REDHEADS 1955 WS G The Man Who Loved Redheads The honourable Mark St. Neots is playing with some chums when he meets and is bowled over by Sylvia. As he grows older he retains his image of this beautiful young girl with the red hair. Through a chance meeting, he can pursue his career in the diplomatic corps as well as the young ladies he meets. Starring: Moira Shearer, John Justin, Denholm Elliott, Harry Andrews, Gladys Cooper 12:40 BETRAYED 1954 PG Betrayed Academy Award winner Clark Gable stars with Lana Turner in this espionage thriller about a World War II Dutch resistance leader who must uncover a double agent among his trusted operatives... before the Nazis receive information that will cost the lives of hundreds of Dutch underground fighters. Also stars Lana Turner and Victor Mature. Starring: Clark Gable, Lana Turner, Victor Mature, Louis Calhern Cons.Advice: Some Violence 15:00 ANCHORS AWEIGH 1945 G Anchors Aweigh Two sailors, one naive, the other experienced in the ways of the world, on liberty in Los Angeles, is the setting for this movie musical. -

Michelle, My Belle

JUDY, JUDY, JUDY ACCESSORIES: Luxury handbag brand Judith Leiber introduces a WWDSTYLE lower-priced collection. Page 11. Michelle, My Belle A rainbow of color may have populated the red carpet at this year’s Oscars, but Best Actress nominee Michelle Williams went countertrend, keeping it simply chic with a Chanel silver sheath dress. For more on the Oscars red carpet, see pages 4 and 5. PHOTO BY DONATO SARDELLA 2 WWDSTYLE MONDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2011 Elizabeth Banks Livia with Tom Ford. and Colin eye Firth. Claire Danes in Chanel with Hugh Dancy Emma Stone in at the Chanel Chanel at the Jennifer dinner. Chanel dinner. Hudson Livia and Colin Firth January Jones in Chanel at the Chanel The Endless Season dinner. Perhaps it was because James Franco — the current “What’s Harvey’s movie?” he asked. “‘The King’s standard-bearer for actor-artistes the world over — Speech’? I liked that very much.” was co-hosting the ceremony, or perhaps a rare SoCal But it wasn’t all high culture in Los Angeles this week. cold front had Hollywood in a more contemplative The usual array of fashion house- and magazine-sponsored mood than normal, but the annual pre-Oscar party bashes, congratulatory luncheons, lesser awards shows rodeo had a definite art world bent this year. and agency schmooze fests vied for attention as well. Rodarte designers Kate and Laura Mulleavy On Wednesday night — a day before the scandal that kicked things off Wednesday night with an exhibit engulfed the house and its designer, John Galliano — of their work (including several looks they created Harvey Weinstein took over as co-host of Dior’s annual for Natalie Portman in “Black Swan”) sponsored Oscar dinner, and transformed it from an intimate affair by Swarovski at the West Hollywood branch of beneath the Chateau Marmont colonnade to a Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art 150-person event that took over the hotel’s entire and an accompanying dinner at Mr. -

Princess Diana –

Princess Diana – Legend of the month “They say it is better to be poor and happy than rich and miserable, but how about a compromise like moderately rich and just moody?” —Princess Diana Born Diana Spencer on July 1, 1961, Princess Diana became Lady Diana Spencer after her father inherited the title of Earl Spencer in 1975. She married heir to the British throne, Prince Charles, on July 29, 1981. They had two sons and later divorced in 1996. Diana died in a car crash after trying to escape the paparazzi in Paris on the night of August 30, 1997. Aristocratic Upbringing British royalty Princess Diana Spencer was born on July 1, 1961, near Sandringham, England. Diana, Princess of Wales, was one of the most adored members of the British royal family. She was the daughter of Edward John Spencer, Viscount Althorp, and Frances Ruth Burke Roche, Viscountess Althorp (later known as the Honorable Frances Shand Kydd). Her parents divorced when Diana was young, and her father won custody of her and her siblings. She was educated first at Riddlesworth Hall and then went to boarding school at West Heath School. She became Lady Diana Spencer after her father inherited the title of Earl Spencer in 1975. Although she was known for her shyness growing up, she did show an interest in music and dancing. Diana also had a great fondness for children. After attending finishing school at the Institut Alpin Videmanette in Switzerland, she moved to London. She began working with children, eventually becoming a kindergarten teacher at the Young England School. -

Smoothing the Wrinkles Hollywood, “Successful Aging” and the New Visibility of Older Female Stars Josephine Dolan

Template: Royal A, Font: , Date: 07/09/2013; 3B2 version: 9.1.406/W Unicode (May 24 2007) (APS_OT) Dir: //integrafs1/kcg/2-Pagination/TandF/GEN_RAPS/ApplicationFiles/9780415527699.3d 31 Smoothing the wrinkles Hollywood, “successful aging” and the new visibility of older female stars Josephine Dolan For decades, feminist scholarship has consistently critiqued the patriarchal underpinnings of Hollywood’s relationship with women, in terms of both its industrial practices and its representational systems. During its pioneering era, Hollywood was dominated by women who occupied every aspect of the filmmaking process, both off and on screen; but the consolidation of the studio system in the 1920s and 1930s served to reduce the scope of opportunities for women working in off-screen roles. Off screen, a pattern of gendered employment was effectively established, one that continues to confine women to so-called “feminine” crafts such as scriptwriting and costume. Celebrated exceptions like Ida Lupino, Dorothy Arzner, Norah Ephron, Nancy Meyers, and Katherine Bigelow have found various ways to succeed as producers and directors in Hollywood’s continuing male-dominated culture. More typically, as recently as 2011, “women comprised only 18% of directors, executive producers, cinematographers and editors working on the top 250 domestic grossing films” (Lauzen 2012: 1). At the same time, on-screen representations came to be increasingly predicated on a gendered star system that privileges hetero-masculine desires, and are dominated by historically specific discourses of idealized and fetishized feminine beauty that, in turn, severely limit the number and types of roles available to women. As far back as 1973 Molly Haskell observed that the elision of beauty and youth that underpins Hollywood casting impacted upon the professional longevity of female stars, who, at the first visible signs of aging, were deemed “too old or over-ripe for a part,” except as a marginalized mother or older sister. -

EARL CAMERON Sapphire

EARL CAMERON Sapphire Reuniting Cameron with director Basil Dearden after Pool of London, and hastened into production following the Notting Hill riots of summer 1958, Sapphire continued Dearden and producer Michael Relph’s valuable run of ‘social problem’ pictures, this time using a murder-mystery plot as a vehicle to sharply probe contemporary attitudes to race. Cameron’s role here is relatively small, but, playing the brother of the biracial murder victim of the title, the actor makes his mark in a couple of memorable scenes. Like Dearden’s later Victim (1961), Sapphire was scripted by the undervalued Janet Green. Alex Ramon, bfi.org.uk Sapphire is a graphic portrayal of ethnic tensions in 1950s London, much more widespread and malign than was represented in Dearden’s Pool of London (1951), eight years earlier. The film presents a multifaceted and frequently surprising portrait that involves not just ‘the usual suspects’, but is able to reveal underlying insecurities and fears of ordinary people. Sapphire is also notable for showing a successful, middle-class black community – unusual even in today’s British films. Dearden deftly manipulates tension with the drip-drip of revelations about the murdered girl’s life. Sapphire is at first assumed to be white, so the appearance of her black brother Dr Robbins (Earl Cameron) is genuinely astonishing, provoking involuntary reactions from those he meets, and ultimately exposing the real killer. Small incidents of civility and kindness, such as that by a small child on a scooter to Dr Robbins, add light to a very dark film. Earl Cameron reprises a role for which he was famous, of the decent and dignified black man, well aware of the burden of his colour.