Drug Trafficking INT 2/24/04 9:05 AM Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100Fires Books PO Box 27 Arcata, CA 95518 180-Movement for Democracy and Education PO Box 251701 Little Rock

100Fires Books PO Box 27 Arcata, CA 95518 www.100fires.com 180Movement for Democracy and Education PO Box 251701 Little Rock, AR 72225 USA Phone: (501) 2442439 Fax: (501) 3743935 [email protected] www.corporations.org/democracy/ 1990 Trust Suite 12 Winchester House 9 Cranmer Road London SW9 6EJ UK Phone: 020 7582 1990 Fax: 0870 127 7657 www.blink.org.uk [email protected] 20/20 Vision Jim Wyerman, Executive Director 1828 Jefferson Place NW Washington, DC 20036 Phone: (202) 8332020 Fax: (202) 8335307 www.2020vision.org [email protected] 2030 Center 1025 Connecticut Avenue NW Suite 205 Washington, DC 20036 Phone: (877) 2030ORG Fax: (202) 9555606 www.2030.org [email protected] 21st Century Democrats 1311 L Street, NW Suite 300 Washington, DC 20005 Phone: (202) 6265620 Fax: (202) 3470956 www.21stDems.org [email protected] 4H 7100 Connecticut Avenue Chevy Chase, MD 20815 Phone: (301) 9612983 Fax: (301) 9612894 www.fourhcouncil.edu 50 Years is Not Enough 3628 12th Street NE Washington, DC 20017 Phone: 202IMFBANK www.50years.org [email protected] 911 Media Arts Center Fidelma McGinn, Executive Director 117 Yale Avenue N. Seattle, WA 98109 Phone: (206) 6826552 Fax: (206) 6827422 www.911media.org [email protected] AInfos Radio Project www.radio4all.net AZone 2129 N. Milwaukee Avenuue Chicago, IL 60647 Phone: (312) 4943455 www.azone.org [email protected] A.J. Muste Memorial Institite 339 Lafayette Street New York, NY 10012 Phone: (212) 5334335 www.ajmuste.org [email protected] ABC No Rio 156 Rivington Street New York, NY 100022411 Phone: -

Razor Wire Summer 2006

Working to end drug war injustice! Vol. 9 No. 1 Razor Wire Summer 2006 CONTENTS: • Director’s Message — Page 2 • Prison Commission Releases Final Report: Confronting Confinement — Page 3 • Convict Nation, by Silja J. A. Talvi — Page 4 • Eye On Congress — Pages 6, 14 • Five Grams of Coke: Racism, Moralism and White Public Opinion on Sanctions for First Time Possession — Page 7 • NFL Legend Carl Banks Supports Children Of Incarcerated Parents — Page 10 • NASCAR Team Promotes Federal Parole — Page 10 • The WALL: Cynthia Clark — Page 11 • Law Library — Page 12 • Editorial: We Were Hijacked — Page 13 • Battle Over California’s Proposition 36 To Head To Court — Page 15 • More Local Scenes — Pages 16-17 • In The News — Pages 18-19 • I Got Published! — Page 20 • Mail Call — Page 21 • Upcoming Events — Page 22 • US Voters Support Prisoner Rehabilitation — Page 22 • November Coalition History: 1998 to 2000 — Page 23 • Soap And Sentencing — Page 24 • Friends Of November Coalition Running For Office — Page 25 • The WALL: Penny Spence — Page 27 • Editor’s Notes — Page 28 • Editorial: Government Informers — Page 29 • A Message From Leonard Peltier — Page 29 • Let’s Miss This Golden Opportunity — Page 30 • Other Grassroots Groups — Page 32 Architects / Designers / Planners for Social Responsibility — pages 8-9 November Coalition - The Razor Wire www.november.org PAGE 1 A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR WE CAN STOP BLAMING OURSELVES FOR PROBLEMS WE DIDN’T CREATE, AND CHALLENGE THE IMPOSED SYSTEM THAT By Nora Callahan, Executive Director GIVES POWER TO MULTI-BILLION- DOLLAR CORPORATIONS, A SYSTEM THAT DISMISSES ORDINARY PEOPLE WHO ASK FOR IMMEDIATE CHANGES OF COURSE AND, IF NOT FOR US NOW, OUR It’s Not Your Fault CHILDREN’S FUTURE. -

October 18, 2016 the Honorable Tom Reed U.S

October 18, 2016 The Honorable Tom Reed U.S. House of Representatives 2437 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 cc: Speaker Paul Ryan, Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, Rep. Bob Goodlatte, Rep. John Conyers. RE: Opposition to H.R. 6158, the HELP Act of 2016 Dear Rep. Reed, On behalf of a coalition of groups working toward criminal justice reform, we write to respectfully express our opposition to your bill, H.R. 6158, the HELP Act of 2016. H.R. 6158 would expose individuals caught selling fentanyl or a substance containing fentanyl to mandatory life without parole or death penalty sentences. Such an approach would be a dramatic step in the wrong direction at a time when there is a bipartisan movement aimed at rolling back the harsh drug sentences created in 1986. H.R. 6158 would also exacerbate the opioid epidemic our country is currently undergoing. The bill is out of step with the times, science, data, and public opinion and doubles down on 30 years of ineffective drug policy, and we ask that it be revised. We are not unaware of the growing challenges around fentanyl and heroin in many communities, with an increasing number of overdose deaths attributed to the presence of fentanyl.1 But H.R. 6158 will not deter this drug’s use. Fentanyl is a synthetic, rapid-acting opiate analgesic, commonly added to heroin to increase its potency. Because fentanyl is hundreds of times more powerful than heroin,2 individuals high on the international supply chain of heroin trafficking are incentivized to strengthen a diluted product.3 The head of the DEA testified before the Senate in June 2016 that fentanyl was often added high up and early in the supply chain – in China and Mexico - long before drugs enter the United States.4 By the time the drugs make it to American streets and homes, street-level sellers and their buyers are unaware of the makeup of their product and its potency.5 H.R. -

Who's Really in Prison for Marijuana?

Drug legalizers want you to believe a lie— that our prisons are filled with marijuana smokers. In fact, the vast majority of drug prisoners are violent criminals, repeat offenders, traffickers, or all of the above. OFFICE OF NATIONAL DR UG CONTROL POLIC Y Who’s Really in Prison for Marijuana? Drug legalizers want you to believe a lie— that our prisons are filled with marijuana smokers. In fact, the vast majority of drug prisoners are violent criminals, repeat offenders, traffickers, or all of the above. OFFICE OF NATIONAL DRUG CONTROL POLICY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) extends special thanks to the following individuals and organizations for their help in researching and reviewing this booklet. Without their valuable insights and patient guidance, this project would not have been possible: Allen Beck, Christopher Mumola, and Matthew Durose, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Gregory Mitchell and Wes Clark, U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration; Louis Reedt and Christine Kitchens, U.S. Sentencing Commission; Wayne Raabe, Criminal Division, U.S. Department of Justice; Donna Eide, U.S. Attorney’s Office, Southern District of Indiana; Randall Hensel, U.S. Attorney’s Office, Pensacola, Florida; Patricia White and Tourine Phillips, National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges; Alec Christoff, National Drug Court Institute; Debra Whitcomb, American Prosecutors Research Institute; Joe Weedon, American Correctional Association; Rosalie Liccardo Pacula, RAND; Jonathan P. Caulkins, H. John Heinz III School of Public Policy & Management, Carnegie Mellon University; Jamie Chriqui and Joanna King, The MayaTech Corporation; and Jeffrey Robinson, writer. WHO’S RE AL LY IN PRISON FOR MARIJUANA? 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD . -

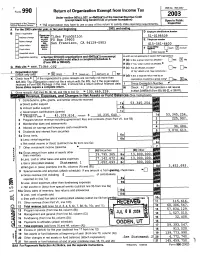

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

OMB No 1545.0047 Tax 'Form 990 1 Return of Organization Exempt from Income Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(aX1) of the Internal Revenue Code 2003 (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) Open to Public Department of the Treasury i rements . Inspection Internal Revenue Service P- The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting A For the 2003 calm or tax and D Employer Identification Number B Check if applicable Please use Address change IRS label Tides Foundation 51-0198509 or print Telephone number Name change or type . p0 Box 29903 s.. San Francisco, CA 94129-0903 Initial return specific 415-561-6400 instruc" F Cash rX] Final return tons. methodtIn9 Other (speafy) `- Amended return H and I are not applrcable to section 527 organizations Application pending e Section 501(cx3) organizations and 4947(a)(''I) nonexempt charitable trusts must attach a completed schedule A H (a) Is this a group return for affiliates a Yes ~ No (Form 990 or 990-EZ) . H (b) If 'Yes,' enter number of affiliates 0' Web site: Tides . orQ FI (C) Are all affiliates included a Yes ~ No (If 'No,' attach a list See instructions ) ELS -m- SQT(cj 3-- fmsert no ) 4947(a)(1) or 527 chE - H (d) Is this a separate return filed by an here if the organization's gross receipts are normally not more than orga nization covered by a g r oup rulings K Check 'I F] E] Yes n No not file a return with the IRS, but if the organization $25,000 . -

MICROCOMP Output File

S. HRG. 106±299 CRISIS IN COLOMBIA: U.S. SUPPORT FOR PEACE PROCESS AND ANTI-DRUG EFFORTS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 6, 1999 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 61±871 CC WASHINGTON : 2000 VerDate 11-SEP-98 14:14 Mar 24, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 61871 SFRELA1 PsN: SFRELA1 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS JESSE HELMS, North Carolina, Chairman RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware PAUL COVERDELL, Georgia PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts ROD GRAMS, Minnesota RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming BARBARA BOXER, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey BILL FRIST, Tennessee STEPHEN E. BIEGUN, Staff Director EDWIN K. HALL, Minority Staff Director (II) VerDate 11-SEP-98 14:14 Mar 24, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 61871 SFRELA1 PsN: SFRELA1 CONTENTS Page Coverdell, Hon. Paul, U.S. Senator from Georgia, Chairman, Subcommittee on Western Hemisphere, Peace Corps, Narcotics, and Terrorism, Foreign Relations Committee ............................................................................................ 2 DeWine, Hon. Mike, U.S. Senator from Ohio ........................................................ 8 Prepared statement of ...................................................................................... 9 McCaffrey, Hon. Barry, Director, Office of National Drug Control Policy .......... 14 Prepared statement of ...................................................................................... 18 Responses to additional questions for the record from Senator Coverdell . -

Americas Overview

AMERICAS 91 OVERVIEW Human Rights Developments dence that the country’s armed forces contin- Contrasts marked the year in the Ameri- ued to be implicated in human rights violations cas. The already dire situation in Colombia as well as in support for the paramilitary deteriorated further, and the deep political groups responsible for the majority of serious and institutional crisis in Peru continued to abuses. Troops attacked indiscriminately and make broad respect for human rights but a killed civilians, among them six elementary distant goal. On the other hand, in Mexico, school children on a field trip near Pueblo where presidential elections in July heralded Rico, Antioquia, on August 15. According to the first change of party in the presidential witnesses, soldiers fired on the group for forty mansion in more than seventy years, hopes minutes. grew that the new president would undertake The character of the conflict changed much-needed human rights reforms. A coup with the entry of the United States as a major in Ecuador and a failed coup attempt in investor, providing an infusion of U.S. $1.3 Paraguay reminded the region of the fragility billion of mostly military aid for the govern- of democracy. Meanwhile, Chile moved for- ment. The package included seven rigorous ward in its attempt to prosecute former human rights conditions, including the need dictator Augusto Pinochet, and an Argentine for the Colombian armed forces to demon- judge requested his extradition to face crimi- strate a break with the paramilitaries. The U.S. nal charges for the 1974 Buenos Aires car- secretary of state certified that Colombia had bombing of former Chilean army commander- met only one of the conditions, related to in-chief general Carlos Prats and his wife. -

From the Law to the Global Market: the Campaign of the U'wa Indigenous People in Colombia (1995-2010)

From the Law to the Global Market: The Campaign of the U'wa Indigenous People in Colombia (1995-2010) By Pablo Rueda A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Calvin Morrill Co-Chair Professor Malcolm M. Feeley Co-Chair Professor Martin M. Shapiro Professor Laura Nader Spring 2012 Abstract From the Law to the Global Market: The Campaign of the U'wa Indigenous People in Colombia (1995-2010) by Pablo Rueda Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy University of California, Berkeley Professors Calvin Morrill Chair and Malcolm M. Feeley, Chairs This dissertation uses the campaign of Colombia’s U’wa indigenous people against oil extraction in their land as a case study to understand the impact of the state, the law and the market over the tactics and scale of social movements. It studies how the campaign shifted away from litigation, expanded its scale transnationally and started using the tools available in the global market economy to prevent oil exploration in the U’wa land. The dissertation suggests the need to understand social movement tactics as a complex, multidimensional phenomenon in order to capture the relation between activism and multiple institutions. Finally, it also provides a framework to understand the relation between different tactics and institutions that helps to explain the roles of economic, political, and legal factors in providing the resources and opportunities for tactical innovation and transnational activism. -

Working Paper Series Paper No

DANTE B. FASCELL NORTH-SOUTH CENTER WORKING PAPER NUMBER FOURTEEN 1 The Dante B. Fascell North-South Center Working Paper Series Paper No. 14 March 2003 Was Failure Avoidable? Learning From Colombia’s 1998-2002 Peace Process Adam Isacson http://www.miami.edu/nsc/publications/NSCPublicationsIndex.html#WP The Dante B. Fascell North South Center UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI DANTE B. FASCELL NORTH-SOUTH CENTER WORKING PAPER NUMBER FOURTEEN 2 The following is a Working Paper of The Dante B. Fascell North-South Center at the University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida. As this paper is a work-in-progress, the author(s) and the North-South Center wel- come comments and critiques from colleagues and students of security studies, environmental issues, and civil society participation. Comments may be e-mailed to the series editor, Jeffrey Stark, at [email protected]. © 2003 All North-South Center Working Papers are protected by copyright. Published by the University of Miami North-South Center. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Conventions. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s), not The Dante B. Fascell North-South Center, which is a nonpartisan public policy and research institution. Inquiries and submissions to the North-South Center Working Papers Series may be sent to Jeffrey Stark, Director of Research and Studies, via e-mail attachment to [email protected], including author’s name, title, affiliation, and e-mail address. ISBN 1-57454-138-2 March 2003 DANTE B. FASCELL NORTH-SOUTH CENTER WORKING PAPER NUMBER FOURTEEN 3 WAS FAILURE AVOIDABLE? LEARNING FROM COLOMBIA’S 1998-2002 PEACE PROCESS Adam Isacson A Bitter End olombians had never seen President Andrés Pastrana as angry or as dejected as he appeared on television C the night of Wednesday, February 20, 2002. -

War on Drugs - Wikipedia 17.08.17, 11�40 War on Drugs from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

War on Drugs - Wikipedia 17.08.17, 1140 War on Drugs From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "The War on Drugs" is an American term[6][7] usually applied to the United States government's campaign of prohibition of drugs, military aid, and military intervention, with the stated aim being to reduce the illegal drug trade.[8][9] This initiative includes a set of drug policies that are intended to discourage the production, distribution, and consumption of psychoactive drugs that the participating governments and the UN have made illegal. The term was popularized by the media shortly after a press conference given on June 18, 1971, by United States President Richard Nixon—the day after publication of a special message from President Nixon to As part of the War on Drugs, the US the Congress on Drug Abuse Prevention and Control—during which spends approximately $500 million per year on aid for Colombia, largely used to he declared drug abuse "public enemy number one". That message to combat guerrilla groups such as FARC the Congress included text about devoting more federal resources to that are involved in the illegal drug the "prevention of new addicts, and the rehabilitation of those who trade.[1][2][3][4][5] are addicted", but that part did not receive the same public attention as the term "war on drugs".[10][11][12] However, two years prior to this, Nixon had formally declared a "war on drugs" that would be directed toward eradication, interdiction, and incarceration.[13] Today, the Drug Policy Alliance, which advocates for an end to the -

Psychedelic Resource List (PRL) Was Born in 1994 As a Subscription-Based Newsletter

A Note from the Author… The Psychedelic Resource List (PRL) was born in 1994 as a subscription-based newsletter. In 1996, everything that had previously been published, along with a bounty of new material, was updated and compiled into a book. From 1996 until 2004, several new editions of the book were produced. With each new version, a decrease in font size correlated to an increase in information. The task of revising the book grew continually larger. Two attempts to create an updated fifth edition both fizzled out. I finally accepted that keeping on top of all of the new books, businesses, and organizations, had become a more formidable challenge than I wished to take on. In any case, these days folks can find much of what they are looking for by simply using an Internet search engine. Even though much of the PRL is now extremely dated, it occurred to me that there are two reasons why making it available on the web might be of value. First, despite the fact that a good deal of the book’s content describes things that are no longer extant, certainly some of the content relates to writings that are still available and businesses or organizations that are still in operation. The opinions expressed regarding such literature and groups may remain helpful for those who are attempting to navigate the field for solid resources, or who need some guidance regarding what’s best to avoid. Second, the book acts as a snapshot of underground culture at a particular point in history. As such, it may be found to be an enjoyable glimpse of the psychedelic scene during the late 1990s and early 2000s. -

Medical Marijuana the War on Drugs and the Drug Policy Reform Movement

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ FROM THE FRONTLINES TO THE BOTTOM LINE: MEDICAL MARIJUANA THE WAR ON DRUGS AND THE DRUG POLICY REFORM MOVEMENT A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction Of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in SOCIOLOGY by Thomas R. Heddleston June 2012 The Dissertation of Thomas R. Heddleston is approved: ____________________________________ Professor Craig Reinarman, Chair ____________________________________ Professor Andrew Szasz ____________________________________ Professor Barbara Epstein ___________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Thomas R. Heddleston 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter I: The History, Discourse, and Practice of Punitive Drug Prohibition 38 Chapter II: Three Branches Of Reform, The Drug Policy Reform Movement From 1964 To 2012 91 Chapter III: Sites of Social Movement Activity 149 Chapter IV: The Birth of Medical Marijuana In California 208 Chapter V: A Tale of 3 Cities Medical Marijuana 1997-2011 245 Chapter VI: From Movement to Industry 303 Conclusion 330 List of Supplementary Materials 339 References 340 iii LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES Table 2.1: Major Organizations in the Drug Policy Reform Movement by Funding Source and Organizational Form 144 Table 3.1: Characteristics of Hemp Rallies Attended 158 Table 3.2: Drug Policy Organizations and the Internet 197 Figure 4.1: Proposition 215 Vote November 1996 241 Table 5.1: Political Opportunity Structures and Activist Tools 251 Table 5.2: Key Aspects of Political Opportunity Structures at 3 Levels of Government 263 Figure 5.1: Medical Cannabis Dispensaries by Region and State 283 iv ABSTRACT Thomas R. Heddleston From The Frontlines to the Bottom Line: Medical Marijuana the War On Drugs and the Drug Policy Reform Movement The medical marijuana movement began in the San Francisco Bay Area in the early 1990s in a climate of official repression.