From Lumberjills to Wooden Wonders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghana Forest and Wildlife Policy

REPUBLIC OF GHANA GHANA FOREST AND WI LDLIFE POLICY Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources Accra- Ghana 2012 Ghana Forest and Wildlife Policy © Ministry of Land and Natural Resources 2012 For more information, call the following numbers 0302 687302 I 0302 66680 l 0302 687346 I 0302 665949 Fax: 0302 66680 t -ii- Ghana Forest and Wildlife Policy CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ... ... .. .............. .. ..... ....... ............ .. .. ...... .. ........ .. vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ................................................................. .......................... viii FOREWORD ........................................................................................... ...................... ix 1.0 PREAMBLE ............ .. .................................................................. .............................. ! 2.0 Overview Of Forest And Wildlife Sector ..... ............................ .................... ... 3 2 .1 Forest and Wildlife Conservation 3 2.1.1 Forest Plantation Development 4 2.1.2 Collaborative Forest Management 5 2.2 Challenges and Issues in the Forest and Wildlife Sector 2.3 National Development Agenda and Forest and Wildlife Management 2.4 International Concerns on the Global Environment 9 3.0 THE POLICY FRAMEWORK ......................... .. ............................................ ........ 10 3.1 Guiding Principles 10 4 .0 THE FOREST AND WILDLIFE POLICY STATEMENT ............................ ......... 12 4 .1 Aim of the Policy 12 4.2 Objectives of the Policy 12 5.0 Policy Strategies ............ -

Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance

ETF r n i s s u e N o . 5 5 , m a R c h 2 0 1 4 n E w s 55 RodeRick Zagt Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance EuropEan Tropical ForEsT ResEarch Network EuRopEan TRopIcaL ForesT REsEaRch NetwoRk ETFRN News Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance IssuE no. 55, maRch 2014 This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European commission’s Thematic programme for Environment and sustainable management of natural Resources, Including Energy; the European Forest Institute’s Eu REDD Facility; the German Federal ministry for Economic cooperation and Development (BmZ); and the Government of the netherlands. The views expressed herein are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of ETFRn, Tropenbos International, the European union or the other participating organizations. published by: Tropenbos International, wageningen, the netherlands copyright: © 2014 ETFRn and Tropenbos International, wageningen, the netherlands Texts may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, citing the source. citation: Broekhoven, Guido and marieke wit (eds.). (2014). Linking FLEGT and REDD+ to Improve Forest Governance. Tropenbos International, wageningen, the netherlands. xx + 212 pp. Editors: Guido Broekhoven and marieke wit Final editing and layout: Patricia halladay Graphic Design IsBn: 978-90-5113-116-1 Issn: 1876-5866 cover photo: women crossing a bridge near kisangani, DRc. Roderick Zagt printed by: Digigrafi, Veenendaal, the netherlands available from: ETFRn c/o Tropenbos International p.o. Box 232, 6700 aE wageningen, the netherlands tel. +31 317 702020 e-mail [email protected] web www.etfrn.org This publication is printed on Fsc®-certified paper. -

Human-Wildlife Conflicts

Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Issue 2 Human-Wildlife Conflicts Editor: M. Laverdière Assistant Editors: L. Bakker, A. Ndeso-Atanga FAO Regional Office for Africa [email protected] www.fao.org/world/regional/raf/workprog/forestry/magazine_en.htm FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANISATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Accra, Ghana 2007 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Chief, Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Communication Division, FAO,Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected]. ©FAO 2007 Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Issue 2 Table of Contents Page Editorial 1 News News in Africa 2 News Worldwide 3 FAO News 5 Thematic News in Africa 6 Thematic News Worldwide 6 Special Feature Human-Wildlife Conflict: A Case for Collaboration 8 Madden, F. -

Studham Common Walk Are Earth Or Grass

to Dunstable B4541 Downs enjoy - explore - enhance B4506 Whipsnade B4540 things to do & see around Studham to Dunstable your local environment Annual Fair every May Whipsnade Wild Animal Park Cricket, football, tennis. Playing fields A5 Dedmansey St Mary's Church, if locked key from 01582 873257 Dagnall Wood Studham Nursery, Jean & John, Clements End Rd 01582 872958 Studham Studham Common Red Lion PH, Debbie & Graham, 01582 872530 Markyate The Bell PH, Steve & Sharon, 01582 872460 Studham Harpers Farm Shop, Dunstable Road, 01582 872001 Whipsnade Tree Cathedral (NT) 01582 872406 A4146 Whipsnade Wild Animal Park 01582 872171 Common Dunstable Downs (NT) 01582 608489 Little Gaddesden London Gliding Club 01582 663419 to Hemel Hempstead things to note... how to get there... badger Please remember the old country code speckled wood TAKE nothing but photographs - LEAVE nothing but Studham lies 10km (6miles) west of the M1 (Junction 9 or 10) and the A5. It is 6km (4miles) due south of Dunstable on the B4541 footprints and 12km (7miles) north of Hemel Hempstead, just off the A4146. There are litter bins and dog waste bins in the car parks Please do not pick wild flowers or dig up plants Public transport: Traveline 0870 608 2 608 Local by-laws do not permit cars, motor bikes, lighting of fires or flying model aircraft on the common Parking: There are small car parks on East and Middle P Commons (see main map) Do not leave valuables in your parked car for more information... if you enjoyed this walk... Visit the website of the North Chilterns Trust www.northchilternstrust.co.uk which has a link to Studham If this walk has whetted your appetite, there are many other beautiful walks to explore For information on the Friends of Studham Common, phone John McDougal on 01582 873257 around here. -

Forest Investment Program Ghana

FOREST INVESTMENT PROGRAM GHANA: PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP FOR THE RESTORATION OF DEGRADED FOREST RESERVE THROUGH VCS AND FSC CERTIFIED PLANTATIONS USD 10 million May 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I ACRONYMS II COVER PAGE 1 BACKGROUND 4 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 11 FIT WITH FIP INVESTMENT CRITERIA 15 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 19 ANNEX 1: INVESTMENTS IN SUSTAINABLE FORESTRY – A BRIEF PRESENTED TO AFDB’S CREDIT COMMITTEE 19 i ACRONYMS AfDB African Development Bank CIF Climate Investment Funds DSCR Debt Service Coverage Ratio ESAP Environmental Assessment Procedures FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FC Ghana Forest Commission FIP Forest Investment Program FSC Forest Stewardship Council FWP Forest and Wildlife Policy 1994 GoG Government of Ghana IP Investment Plan ISS Integrated Safeguards System ITTO The International Tropical Timber Organization NFPDP National Forest Plantation Development Program PPP Public-Private Partnership REDD+ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation VCS Verified Carbon Standard ii COVER PAGE Public-Private Partnership for the restoration of Degraded Forest Reserve through VCS and FSC Certified Plantations. 1. Country/Region: Ghana 2. CIF Project ID#: (Trustee will assign ID) 3. Source of Funding: FIP PPCR SREP 4. Project/Program Title: Ghana: Public-Private Partnership for the restoration of Degraded Forest Reserve through VCS and FSC Certified Plantations. 5. Type of CIF Investment: Public Private Mixed 6. Funding Request in million Grant: Non-Grant: USD equivalent: USD 10 million Concessional Loan 7. Implementing MDB(s): African Development Bank 8. National Implementing Not Applicable. Agency: 9. MDB Focal Point and Headquarters- Focal Point: TTL: Project/Program Task Gareth Phillips Richard Fusi [email protected] / Team Leader (TTL): [email protected] / Leandro Azevedo [email protected] 10. -

A Review of Policy Ad Regulatory Discourses O Timber Legality

One hundred years of forestry in Ghana: A review of policies and legislation K. A. Oduro et al. OE HUDRED YEARS OF FORESTRY I GHAA: A REVIEW OF POLICY AD REGULATORY DISCOURSES O TIMBER LEGALITY K. A. Oduro 1, E. Marfo 1, V. K. Agyeman 1 and K. Gyan 2 1CSIR-Forestry Research Institute of Ghana, University Post Office Box UP 63, KUST, Kumasi Ghana 2Ministry of Lands and atural Resources, Accra Ghana Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] ABSTRACT Ghana has seen incremental shifts in forest policy, legislation and management approaches in the last one hundred years. Information on forests through time and knowledge of policy evolution, laws, and participants and institutions involved in the policy process is important to deal with complexities associated with timber legality and trade. This paper reviews the evolution of forest policies and regulations on timber legality in Ghana using a historical discourse analysis. It characterises the regulatory discourses of successive forest policies and legislations and the extent to which policy and policy instruments, particularly on trade of legal timber, reflect the hard, soft, and smart regulatory discourses. The paper shows that until the mid-1980s Ghana’s timber regulation policies had been characterized largely by state control using top-down management and hard law regulations. The mid- 1980s and the early 1990s represent an interface between the softening of state control and the emergence of de-regulation and soft law discourses. The 1994 Forest and Wildlife Policy reflected this interface calling for improved collaboration with communities and market-driven strategies to optimize forest use. -

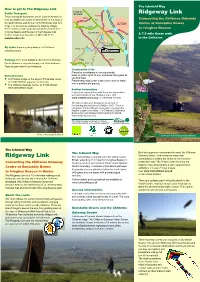

Ridgeway Link 2012

The Icknield Way How to get to The Ridgeway Link 12 Leighton Public Transport: Ridgeway Link Buzzard There is a regular bus service (no.61 Luton to Aylesbury) A5120 A4012 M1 Connecting the Chilterns Gateway from Dunstable town centre to West Street, at the edge of A5 Dunstable Downs and the start of the Ridgeway Link (see LUTON Centre at Dunstable Downs map). This bus service continues to Ivinghoe Village. A505 to Ivinghoe Beacon There is then a 2 mile walk along footpaths from here to 11 Ivinghoe Beacon and the start of the Ridgeway Link. Dunstable A505 A 7.5 mile linear walk Further details from Traveline tel 0871 200 22 33 www.traveline.info P in the Chilterns 10 Whipsnade By cycle: there is cycle parking at the Chilterns Ivinghoe Gateway Centre. P The Ridgeway Link 9 Parking: there is car parking at the Chilterns Gateway Tring A4146 Centre (there is a car park charge), and at the National A41 Trust car park near Ivinghoe Beacon. Countryside Code Please be considerate in the countryside: Refreshments Keep to public rights of way, and leave farm gates as Old Hunters Lodge on the edge of Whipsnade Green, you find them. Please keep dogs under close control and on leads tel 01582 872228 www.old-hunters.com where animals are grazing. The Chilterns Gateway Centre, tel 01582 500920 www.nationaltrust.org.uk Further Information If you have enjoyed this walk there are many other wonderful walks in the Chilterns area. Visit www.chilternsaonb.org or call 01844 355500. The Chiltern Hills were designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1965. -

British Lichen Society Bulletin No

1 BRITISH LICHEN SOCIETY OFFICERS AND CONTACTS 2010 PRESIDENT S.D. Ward, 14 Green Road, Ballyvaghan, Co. Clare, Ireland, email [email protected]. VICE-PRESIDENT B.P. Hilton, Beauregard, 5 Alscott Gardens, Alverdiscott, Barnstaple, Devon EX31 3QJ; e-mail [email protected] SECRETARY C. Ellis, Royal Botanic Garden, 20A Inverleith Row, Edinburgh EH3 5LR; email [email protected] TREASURER J.F. Skinner, 28 Parkanaur Avenue, Southend-on-Sea, Essex SS1 3HY, email [email protected] ASSISTANT TREASURER AND MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY H. Döring, Mycology Section, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, email [email protected] REGIONAL TREASURER (Americas) J.W. Hinds, 254 Forest Avenue, Orono, Maine 04473-3202, USA; email [email protected]. CHAIR OF THE DATA COMMITTEE D.J. Hill, Yew Tree Cottage, Yew Tree Lane, Compton Martin, Bristol BS40 6JS, email [email protected] MAPPING RECORDER AND ARCHIVIST M.R.D. Seaward, Department of Archaeological, Geographical & Environmental Sciences, University of Bradford, West Yorkshire BD7 1DP, email [email protected] DATA MANAGER J. Simkin, 41 North Road, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne NE20 9UN, email [email protected] SENIOR EDITOR (LICHENOLOGIST) P.D. Crittenden, School of Life Science, The University, Nottingham NG7 2RD, email [email protected] BULLETIN EDITOR P.F. Cannon, CABI and Royal Botanic Gardens Kew; postal address Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, email [email protected] CHAIR OF CONSERVATION COMMITTEE & CONSERVATION OFFICER B.W. Edwards, DERC, Library Headquarters, Colliton Park, Dorchester, Dorset DT1 1XJ, email [email protected] CHAIR OF THE EDUCATION AND PROMOTION COMMITTEE: position currently vacant. -

NEWLANDS TREE CATHEDRAL, MILTON KEYNES November 2018

Understanding Historic Parks and Gardens in Buckinghamshire The Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust Research & Recording Project NEWLANDS TREE CATHEDRAL, MILTON KEYNES November 2018 The Stanley Smith (UK) Horticultural Trust Bucks Gardens Trust Bucks Gardens Trust, Site Dossier: Newlands Tree Cathedral, Milton Keynes, MKC November 2018 HISTORIC SITE BOUNDARY 2 Bucks Gardens Trust, Site Dossier: Newlands Tree Cathedral, Milton Keynes, MKC November 2018 3 INTRODUCTION Background to the Project This site dossier has been prepared as part of The Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust (BGT) Research and Recording Project, begun in 2014. This site is one of several hundred designed landscapes county‐wide identified by Bucks County Council (BCC) in 1998 (including Milton Keynes District) as potentially retaining evidence of historic interest, as part of the Historic Parks and Gardens Register Review project carried out for English Heritage (now Historic England) (BCC Report No. 508). The list is not definitive and further parks and gardens may be identified as research continues or further information comes to light. Content BGT has taken the Register Review list as a sound basis from which to select sites for appraisal as part of its Research and Recording Project for designed landscapes in the historic county of Bucks (pre‐1974 boundaries). For each site a dossier is prepared by volunteers trained on behalf of BGT by experts in appraising designed landscapes who have worked extensively for English Heritage/Historic England on its Register Upgrade Project. Each dossier includes the following for the site: A site boundary mapped on the current Ordnance Survey to indicate the extent of the main part of the surviving designed landscape, also a current aerial photograph. -

Harpenden Hitchin Luton Leighton Buzzard Tring Dunstable

Little Brickhill Tingrith D OA HAM R HIG P R IO W R To Bletchley B S H A E E I G To Woburn E LL N S Barton 6 A AL To Woburn T 6 D L O 0 L A E E N F Y 0 IK L I O P A N -le-clay Pirton N N G R E R TU R H AR D L O LIN NationalO Cycle Network on-road Harlington G A R D T N O B D N O O E R N A D National Cycle Network traffic-free O E R A D F O N D O Y A A A R L D L W O Suggested road routes TON D AR ROAD 5 W HITCHIN ROAD G B E 5 E 6 R L Great Milton Bryan N Hexton R B A Other off-road cycle routes O HEXT O O H L N W Sharpenhoe R D OAD A D A Brickhill A L Y D O D Places to visit - Lakes O B OA 1 R AR HEATH R see overleaf for details TO N N OAD BEARTON R ROAD PA Harlington O B65 R T 5 1 Places to visit - Countryside/hills K Potsgrove RO U see overleaf for details AD L Pegsdon E R H A5 i E N v X A A e S T L Places to visit - Attractions r U T 1 4 O N 6 F N F Y D 0 D l O V see overleaf for details i O R I A 1 t N O R A R O 2 O S D C R A Stoke Hammond Places to visit - Woods H N 1 D N A A R R U see overleaf for details B B P O E W N Railways station / track H Hitchin O E PIR T Toddington R ON ROAD Café H O Bragenham O A 6 AD D 5 C 6 O B530 BR K R A Bike shop N A B G L O Streatley L 6 L E I T U 0 I F H N Heath A505 N G 2 F I T H S E D WAY Take careBattlesden location E N L O A L R A 1 TE S R M A And Reach N EA O D O R L Upper R E A A National Cycle Network route number N N R GIG LAN O E O O E D Charlton A D T D A D L A D Sundon A A O D R O R 0 A O R 0-150 metre contour Y H R 2 E L C 1 T N E EA E 5 TR O S R T A T 150-170 metre contour H E C G L -

Reader 19 05 19 V75 Timeline Pagination

Plant Trivia TimeLine A Chronology of Plants and People The TimeLine presents world history from a botanical viewpoint. It includes brief stories of plant discovery and use that describe the roles of plants and plant science in human civilization. The Time- Line also provides you as an individual the opportunity to reflect on how the history of human interaction with the plant world has shaped and impacted your own life and heritage. Information included comes from secondary sources and compila- tions, which are cited. The author continues to chart events for the TimeLine and appreciates your critique of the many entries as well as suggestions for additions and improvements to the topics cov- ered. Send comments to planted[at]huntington.org 345 Million. This time marks the beginning of the Mississippian period. Together with the Pennsylvanian which followed (through to 225 million years BP), the two periods consti- BP tute the age of coal - often called the Carboniferous. 136 Million. With deposits from the Cretaceous period we see the first evidence of flower- 5-15 Billion+ 6 December. Carbon (the basis of organic life), oxygen, and other elements ing plants. (Bold, Alexopoulos, & Delevoryas, 1980) were created from hydrogen and helium in the fury of burning supernovae. Having arisen when the stars were formed, the elements of which life is built, and thus we ourselves, 49 Million. The Azolla Event (AE). Hypothetically, Earth experienced a melting of Arctic might be thought of as stardust. (Dauber & Muller, 1996) ice and consequent formation of a layered freshwater ocean which supported massive prolif- eration of the fern Azolla. -

Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Edition 2 English

Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Issue 2 Human-Wildlife Conflicts Editor: M. Laverdière Assistant Editors: L. Bakker, A. Ndeso-Atanga FAO Regional Office for Africa [email protected] www.fao.org/world/regional/raf/workprog/forestry/magazine_en.htm FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANISATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Accra, Ghana 2007 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Chief, Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Communication Division, FAO,Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected]. ©FAO 2007 Nature & Faune Vol. 21, Issue 2 Table of Contents Page Editorial 1 News News in Africa 2 News Worldwide 3 FAO News 5 Thematic News in Africa 6 Thematic News Worldwide 6 Special Feature Human-Wildlife Conflict: A Case for Collaboration 8 Madden, F.