Babylonian Liturgies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Far? (Acts 17:16-34), June 22/23, 2013

How Far? June 22/23, 2013 Digging Deeper (Questions are on the last page) How Far? Written by: Robert Ismon Brown ([email protected]) Background Notes Key Scripture Text: Acts 17:16-34 Introduction How far can we go with this Jesus thing, anyway? Are there really untouchables in the world that must always remain unreached? What do we do when the neediest people around us simply aren’t like us? For those of us living in the U.S., it’s no longer a question of reaching the world outside, because the world has arrived inside our borders, bringing different languages, different cultures, different faiths, and different ideas. And we are anxious about that, and we imagine that such an onslaught of newcomers means less of everything for us: less jobs, less resources, less healthcare, less social services. Anxiety is commonly born of fear that there will never be enough in a closed economy where the rule is scarcity. “They’ve gone too far…” we say about the policy makers. But not everybody thinks like that. There are some who embrace the vision of a different world, where anxiety is replaced by trusting fidelity and where scarcity is replaced by abundance. Some say that God is the Creator of heaven and earth. Some say the Creator has invested the world with more than enough. Some say that God has already gone the far distance from His infinite self to the world’s finite need, and that He is in fact already in our midst in Jesus of Nazareth. And some say He has providentially brought the mission to us, and so now we must choose whether to see the developments in our generation as a horrible tragedy of epic proportions — an epic fail — or whether to see them as the Great Surprise from the God who wants all of His lost children found. -

Namzitara FS Kilmer

Offprint from STRINGS AND THREADS A Celebration of the Work of Anne Draffkorn Kilmer Edited by WOLFGANG HEIMPEL and GABRIELLA FRANTZ - SZABÓ Winona Lake, Indiana EISENBRAUNS 2011 © 2011 by Eisenbrauns Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America www.eisenbrauns.com Drawing on the cover and beneath the title on p. iii by Cornelia Wolff, Munich, after C. L. Wooley, Ur Excavations 2 (1934), 105. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Strings and threads : a celebration of the work of Anne Draffkorn Kilmer / edited by Wolfgang Heimpel and Gabriella Frantz-Szabó. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57506-227-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn. 2. Music—Middle East—History and criticism. 3. Music archaeology— Middle East. I. Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn. II. Heimpel, Wolfgang. III. Frantz-Szabó, Gabriella. ML55.K55S77 2011 780.9—dc22 2011036676 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. †Ê Contents Preface .............................................................. vii Abbreviations ......................................................... ix GUITTY AZARPAY The Imagery of the Manichean ‘Call’ on a Sogdian Funerary Relief from China ................ 1 DOMINIQUE COLLON Chinless Wonders ................................ 19 JERROLD S. COOPER Puns and Prebends: The Tale of Enlil and Namzitara. 39 RICHARD L. CROCKER No Polyphony before A.D. 900! ...................... 45 DANIEL A. FOXVOG Aspects of Name-Giving in Presargonic Lagash ........ 59 JOHN CURTIS FRANKLIN “Sweet Psalmist of Israel”: The Kinnôr and Royal Ideology in the United Monarchy .............. 99 ELLEN HICKMANN Music Archaeology as a Field of Interdisciplinary Research ........................ -

Burn Your Way to Success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual And

Burn your way to success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual and Incantation Series Šurpu by Francis James Michael Simons A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The ritual and incantation series Šurpu ‘Burning’ is one of the most important sources for understanding religious and magical practice in the ancient Near East. The purpose of the ritual was to rid a sufferer of a divine curse which had been inflicted due to personal misconduct. The series is composed chiefly of the text of the incantations recited during the ceremony. These are supplemented by brief ritual instructions as well as a ritual tablet which details the ceremony in full. This thesis offers a comprehensive and radical reconstruction of the entire text, demonstrating the existence of a large, and previously unsuspected, lacuna in the published version. In addition, a single tablet, tablet IX, from the ten which comprise the series is fully edited, with partitur transliteration, eclectic and normalised text, translation, and a detailed line by line commentary. -

""B T6t @T66~Rtans. ·

THE EXPOSITORY TIMES. (!totta: upon t6t ®tfitfs of t6t ®aB~fonians ""b t6t @t66~rtans. · BY T. G. PINCHES, LL.D., M.R.A.S;, LECTURER IN ASSYRIAN f>.T UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, LONDON. THE earliest beliefs of the Babylonians are gener ocean.I The worship of Merodach was the last ally regarded as having been an.imistic - the important form of the religion of Babylonia, As attribution of a soul to the various powers of to Assyria, the changes seem to have been . nature. Traces of this creed, in fact, are met fewer or non-existent - from first to last the. with in the statements of their beliefs which have people remained faithful to their national go(f come down to us. Thus the first creative power Assur. was the sea (Tiamat or Tiawath), teeming, as it Notwithstanding the homogeneity of the Baby~ does, with so many and such wonderful forms of Ionian religious system, there were many differ life ; and next to the sea, the rivers and streams, ences of belief in the various states of that couritry, represented by the god Ea or Enki, with his each of which-and, indeed, every important city daughter Nin-alJ.a-kuddu, The god of .the air, -worshipped its own special divinity, with his and. of thi1'nder, wind; and rain (Rammapu or consort and attendants. The list of 'these is Rimmon, also known as Addu, Adad, or Hadad), naturally very long, but_ as examples may be men is another example ; and the god of pestilence tioned Anu and !Star at Erech; Enlil and later (Nergal) may also be regarded as being of a on Ninip 2 at Nippur; Enki or Ea at Eridu; similar origin, and perhaps identical with Ugga, Merodach and Zer-pan!tum at Babylon; the the god of death. -

Eski Anadolu Ve Eski Mezopotamya'da Tanrıça Kültleri

T.C. NECMETTİN ERBAKAN ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI ESKİÇAĞ TARİHİ BİLİM DALI ESKİ ANADOLU VE ESKİ MEZOPOTAMYA’DA TANRIÇA KÜLTLERİ KADER BAĞDERE YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ DANIŞMAN: DOÇ. DR. MUAMMER ULUTÜRK KONYA-2021 T.C. NECMETTİN ERBAKAN ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI ESKİÇAĞ TARİHİ BİLİM DALI ESKİ ANADOLU VE ESKİ MEZOPOTAMYA’DA TANRIÇA KÜLTLERİ KADER BAĞDERE YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ DANIŞMAN: DOÇ. DR. MUAMMER ULUTÜRK KONYA-2021 T.C. NECMETTİN ERBAKAN ÜNİVERSİTESİ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü BİLİMSEL ETİK SAYFASI Adı Soyadı Kader Bağdere Numarası 18810501035 Ana Bilim / Bilim Dalı Tarih/Eskiçağ Programı Tezli Yüksek Lisans X Doktora Öğrencinin Tezin Adı Eski Anadolu ve Eski Mezopotamya’da Tanrıça Kültleri Bu tezin hazırlanmasında bilimsel etiğe ve akademik kurallara özenle riayet edildiğini, tez içindeki bütün bilgilerin etik davranış ve akademik kurallar çerçevesinde elde edilerek sunulduğunu, ayrıca tez yazım kurallarına uygun olarak hazırlanan bu çalışmada başkalarının eserlerinden yararlanılması durumunda bilimsel kurallara uygun olarak atıf yapıldığını bildiririm. Öğrencinin Adı Soyadı İmzası i T.C. NECMETTİN ERBAKAN ÜNİVERSİTESİ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü ÖZET Adı Soyadı Kader Bağdere Numarası 18810501035 Tarih/Eskiçağ Tarihi Ana Bilim / Bilim Dalı Tezli Yüksek Lisans X Programı Doktora Öğrencinin Tez Danışmanı Doç. Dr. Muammer Ulutürk Eski Anadolu ve Eski Mezopotamya’da Tanrıça Kültleri Tezin Adı Anadolu ve Mezopotamya yüzyıllar boyunca pek çok medeniyete ev sahipliği yapmıştır. Bu topraklar üzerinde birçok kavim doğmuş, varlığını sürdürmüş ve yok olmuştur. Bu bölgeler çok uluslu bir yapıya sahiptir. Çok uluslu olması, dinin de çok tanrılı olmasına neden olmuştur. Hem Anadolu’da hem Mezopotamya’da birçok tanrıça inanışı oluşmuştur. Anadolu’nun en mühim tanrıçası Kibele’dir. -

The Sumerian King List the Sumerian King List (SKL) Dates from Around 2100 BCE—Near the Time When Abram Was in Ur

BcResources Genesis The Sumerian King List The Sumerian King List (SKL) dates from around 2100 BCE—near the time when Abram was in Ur. Most ANE scholars (following Jacobsen) attribute the original form of the SKL to Utu-hejel, king of Uruk, and his desire to legiti- mize his reign after his defeat of the Gutians. Later versions included a reference or Long Chronology), 1646 (Middle to the Great Flood and prefaced the Chronology), or 1582 (Low or Short list of postdiluvian kings with a rela- Chronology). The following chart uses tively short list of what appear to be the Middle Chronology. extremely long-reigning antediluvian Text. The SKL text for the following kings. One explanation: transcription chart was originally in a narrative form or translation errors resulting from and consisted of a composite of several confusion of the Sumerian base-60 versions (see Black, J.A., Cunningham, and the Akkadian base-10 systems G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., of numbering. Dividing each ante- and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text diluvian figure by 60 returns reigns Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http:// in harmony with Biblical norms (the www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/), Oxford bracketed figures in the antediluvian 1998-). The text was modified by the portion of the chart). elimination of manuscript references Final versions of the SKL extended and by the addition of alternative the list to include kings up to the reign name spellings, clarifying notes, and of Damiq-ilicu, king of Isin (c. 1816- historical dates (typically in paren- 1794 BCE). thesis or brackets). The narrative was Dates. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Language Cited: Hamito-Semitic xv Language Cited: Indo-European xv Abbreviations for some Dictionaries and References xvi Grammatical Terminology and Other Abbreviations and Symbols xvii PREFACE 1 CHAPTER ONE HAMITO-SEMITIC LANGUAGE FAMILY 5 1.1 Hamito-Semitic languages 5 1.1.1 Semitic languages 6 1.1.1.1 Acadian 6 1.1.1.2 Canaanite 6 1.1.1.3 Aramaic 7 1.1.1.4 Classical Arabic 7 1.1.1.5 South Arabic 8 1.1.1.6 Ethiopie or Gefez 8 1.1.2 Hamitic languages 8 1.1.2.1 Egyptian 8 1.1.2.2 Berber 8 1.1.2.3 Cushitic 9 1.1.2.4 Chadic 9 1.2 Late PHS sound system 10 1.2.1 Sound correspondences between Semitic and Egyptian 11 1.2.1.1 Stops 18 1.2.1.2 Fricatives 20 1.2.1.3 Nasals 24 1.2.1.4 Laterals 24 1.2.1.5 R-sound 24 1.2.1.6 Glides 25 1.2.1.7 Consonants /s/, /h/ and ImJ 26 1.2.2 Vowels 29 1.2.3 Diphthongs 33 1.3 Hamito-Semitic grammatical system 34 1.3.1 stem I 35 1.3.2 stem II 35 1.3.3 stem III 35 1.3.4 stem IV 36 1.3.4.1 Other HS causative prefixes 36 1.3.4.2 Hamito-Semitic causative affixes and world’s languages 38 1.3.5 stem V 38 1.3.6 stem VI 39 1.3.7 stem VII 39 1.3.8 stem VIII 40 1.3.9 stem IX 40 1.3.10 stemX 41 1.3.11 stem XI 41 1.3.12 stem XII 41 1.3.13 Some other stems 41 CHAPTER TWO SUMERIAN 43 2.1 Introduction 43 2.1.1 Sumerian dialects: Emegir and Emesal 44 2.1.2 Sumerian and other languages 48 2.1.3 Typological classification of Sumerian 51 2.1.3.1 Typology and stages of language development 52 2.1.4 Sumerian writing system 54 CHAPTER THREE SUMERIAN AND HAMITO-SEMITIC: SOUNDS AND LEXICONS 57 3.1 Introduction 57 3.1.1 -

Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions

MISCELLANEOUS BABYLONIAN INSCRIPTIONS BY GEORGE A. BARTON PROFESSOR IN BRYN MAWR COLLEGE ttCI.f~ -VIb NEW HAVEN YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS MDCCCCXVIII COPYRIGHT 1918 BY YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS First published, August, 191 8. TO HAROLD PEIRCE GENEROUS AND EFFICIENT HELPER IN GOOD WORKS PART I SUMERIAN RELIGIOUS TEXTS INTRODUCTORY NOTE The texts in this volume have been copied from tablets in the University Museum, Philadelphia, and edited in moments snatched from many other exacting duties. They present considerable variety. No. i is an incantation copied from a foundation cylinder of the time of the dynasty of Agade. It is the oldest known religious text from Babylonia, and perhaps the oldest in the world. No. 8 contains a new account of the creation of man and the development of agriculture and city life. No. 9 is an oracle of Ishbiurra, founder of the dynasty of Nisin, and throws an interesting light upon his career. It need hardly be added that the first interpretation of any unilingual Sumerian text is necessarily, in the present state of our knowledge, largely tentative. Every one familiar with the language knows that every text presents many possi- bilities of translation and interpretation. The first interpreter cannot hope to have thought of all of these, or to have decided every delicate point in a way that will commend itself to all his colleagues. The writer is indebted to Professor Albert T. Clay, to Professor Morris Jastrow, Jr., and to Dr. Stephen Langdon for many helpful criticisms and suggestions. Their wide knowl- edge of the religious texts of Babylonia, generously placed at the writer's service, has been most helpful. -

The Lost Book of Enki.Pdf

L0ST BOOK °f6NK1 ZECHARIA SITCHIN author of The 12th Planet • . FICTION/MYTHOLOGY $24.00 TH6 LOST BOOK OF 6NK! Will the past become our future? Is humankind destined to repeat the events that occurred on another planet, far away from Earth? Zecharia Sitchin’s bestselling series, The Earth Chronicles, provided humanity’s side of the story—as recorded on ancient clay tablets and other Sumerian artifacts—concerning our origins at the hands of the Anunnaki, “those who from heaven to earth came.” In The Lost Book of Enki, we can view this saga from a dif- ferent perspective through this richly con- ceived autobiographical account of Lord Enki, an Anunnaki god, who tells the story of these extraterrestrials’ arrival on Earth from the 12th planet, Nibiru. The object of their colonization: gold to replenish the dying atmosphere of their home planet. Finding this precious metal results in the Anunnaki creation of homo sapiens—the human race—to mine this important resource. In his previous works, Sitchin com- piled the complete story of the Anunnaki ’s impact on human civilization in peacetime and in war from the frag- ments scattered throughout Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Hittite, Egyptian, Canaanite, and Hebrew sources- —the “myths” of all ancient peoples in the old world as well as the new. Missing from these accounts, however, was the perspective of the Anunnaki themselves What was life like on their own planet? What motives propelled them to settle on Earth—and what drove them from their new home? Convinced of the existence of a now lost book that formed the basis of THE lost book of ENKI MFMOHCS XND PKjOPHeCieS OF XN eXTfCXUfCWJTWXL COD 2.6CHXPJA SITCHIN Bear & Company Rochester, Vermont — Bear & Company One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.InnerTraditions.com Copyright © 2002 by Zecharia Sitchin All rights reserved. -

3 a Typology of Sumerian Copular Clauses36

3 A Typology of Sumerian Copular Clauses36 3.1 Introduction CCs may be classified according to a number of characteristics. Jagersma (2010, pp. 687-705) gives a detailed description of Sumerian CCs arranged according to the types of constituents that may function as S or PC. Jagersma’s description is the most detailed one ever written about CCs in Sumerian, and particularly, the parts on clauses with a non-finite verbal form as the PC are extremely insightful. Linguistic studies on CCs, however, discuss the kind of constituents in CCs only in connection with another kind of classification which appears to be more relevant to the description of CCs. This classification is based on the semantic properties of CCs, which in turn have a profound influence on their grammatical and pragmatic properties. In this chapter I will give a description of CCs based mainly on the work of Renaat Declerck (1988) (which itself owes much to Higgins [1979]), and Mikkelsen (2005). My description will also take into account the information structure of CCs. Information structure is understood as “a phenomenon of information packaging that responds to the immediate communicative needs of interlocutors” (Krifka, 2007, p. 13). CCs appear to be ideal for studying the role information packaging plays in Sumerian grammar. Their morphology and structure are much simpler than the morphology and structure of clauses with a non-copular finite verb, and there is a more transparent connection between their pragmatic characteristics and their structure. 3.2 The Classification of Copular Clauses in Linguistics CCs can be divided into three main types on the basis of their meaning: predicational, specificational, and equative. -

Lambert Walcot Kadmos 4 Dunnu

WARNING OF COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS1 The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, U.S. Code) governs the maKing of photocopies or other reproductions of the copyright materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, library and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than in private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user maKes a reQuest for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. The Yale University Library reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order, if, in its judgement fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. 137 C.F.R. §201.14 2018 KADMOS ZEITSCHRIFT FOR VOR- UND FRÜHGRIECHISCIIE EPIGRAPHIK IN VERBINDUNG MIT: EMMETT L. BENNETT-MADISON • WILLIAM C. BRICE-MANCHESTER PORPHYRIOS DIKAIOS-WALTHAM • KONSTANTINOS D. KTISTOPOULOS ATHENN. OLIVIER MASSON-PARIS • PIERO MERIGGI-PAVIA • FRITZ SCHACHE RMEYR-WIEN - JOHANNES SUNDWALL-HELSINGFORS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON ERNST GRUMACH BAND IV / HEFT 1 WA LTER DE G R U Y T E R & CO. / BERLIN LUNG - J. G. VERLAG 1TAhCOMP. ~ U CHHANDLUUNG -EORGG REIMER SK IKARL J.TRUBNER TTVE 1965 WILFRED G. LAMBERT and PETER WALCOT1 A NEW BABYLONIAN THEOGONY AND HESIOD A volume of cuneiform texts just published by the British Museum2 contains a short theogony, which is of interest to Classical scholars since it is closer to Hesiod's opening list of gods than any other cuneiform material of this category. -

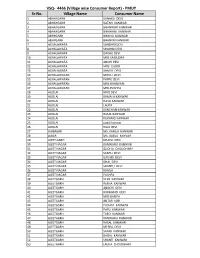

Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name VSQ- 4466 (Village Wise Consumer Report)

VSQ- 4466 (Village wise Consumer Report) - PMUY Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name 1 ABHAYGARH KANAKU DEVI 2 ABHAYGARH RATAN KANWAR 3 ABHAYGARH BHANWAR KANWAR 4 ABHAYGARH BHAWANI KANWAR 5 ABHYGARH BHIKHU KANWAR 6 ABHYGARH BHANVRI KANWAR 7 ACHALAWATA SUNDARI DEVI 8 ACHALAWATA SHOBHA DEVI 9 ACHALAWATA DAKHU DEVI 10 ACHALAWATA MRS SAMUDRA 11 ACHALAWATA ANOPI DEVI 12 ACHALAWATA MRS GUDDI 13 ACHALAWATA KAMLA DEVI 14 ACHALAWATAN MOOLI DEVI 15 ACHALAWATAN PAPPU DEVI 16 ACHALAWATAN MRS BHANVARI 17 ACHALAWATAN MRS PUSHPA 18 AGOLAI HIRO DEVI 19 AGOLAI KAMALA KANWAR 20 AGOLAI HAVA KANWAR 21 AGOLAI LALITA 22 AGOLAI KANCHAN KANWAR 23 AGOLAI RASAL KANWAR 24 AGOLAI RUKAMO KANWAR 25 AGOLAI guddi kanwar 26 AGOLAI RAJO DEVI 27 AJABASAR MS. KAMLA KANWAR 28 AJBAR MS. BABLU KANVAR 29 AJEET GARH DHAPU DEVI 30 AJEET NAGAR KANWARU KANWAR 31 AJEET NAGAR GUDIYA CHOUDHARY 32 AJEET NAGAR SANTU DEVI 33 AJEET NAGAR GAVARI DEVI 34 AJEET NAGAR DHAI DEVI 35 AJEET NAGAR SHANTU DEVI 36 AJEET NAGAR KAMLA . 37 AJEET NAGAR PUSHPA . 38 AJEETGARH VEER KANWAR 39 AJEETGARH REKHA KANWAR 40 AJEETGARH ANACHI DEVI 41 AJEETGARH RUKHAMO DEVI 42 AJEETGARH MRS BABITA 43 AJEETGARH ANTAR KOR 44 AJEETGARH PUSHPA KANWAR 45 AJEETGARH PAPU KANWAR 46 AJEETGARH TARO KANWAR 47 AJEETGARH KANWARU KANWAR 48 AJEETGARH RASAL KANWAR 49 AJEETGARH MEERA DEVI 50 AJEETGARH SAYAR KANWAR 51 AJEETGARH BADAL KANWAR 52 AJEETGARH SHANTI KANWAR 53 AJEETGARH LALITA CHOUDHARY Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name 54 AJEETGARH PEP KANWAR 55 AJEETGARH RASAL KANWAR 56 AJEETGARH JASU KANWAR 57 AJEETGARH LILA KANWAR 58 AJEETGARH KHAMMA DEVI 59 AJIT GADH SUGAN KANWAR 60 AJITGARH CHIMU DEVI 61 AJITGARH KANWARU KANWAR 62 AJJETGADH SOHNI DEVI 63 AKADEEYAWALA MAGEJ KANWAR 64 ALIDAS NAGAR PAPPU KANWAR 65 ALIDAS NAGAR PARVATI DEVI 66 ALIDAS NAGAR NAINU KANWAR 67 ALIDAS NAGAR MOHANI DEVI 68 ALIDAS NAGAR PISTA DEVI 69 ALIDAS NAGAR PRAKASH KANWAR 70 ALIDAS NAGAR NAKHTU DEVI 71 ALIDAS NAGAR DHAPU .