Effective Harp Pedagogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LAVINIA MEIJER HARP DIVERTISSEMENTS SALZEDO | CAPLET | IBERT 28908Laviniabooklet 10-09-2008 11:05 Pagina 2

28908Laviniabooklet 10-09-2008 11:05 Pagina 1 CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 28908 LAVINIA MEIJER HARP DIVERTISSEMENTS SALZEDO | CAPLET | IBERT 28908Laviniabooklet 10-09-2008 11:05 Pagina 2 As a little girl of eight, I was already captivated by the magical sounds of the harp, so pure and rich. Once I discovered the instrument’s wealth of possibilities during my first lessons and my years at the conservatory, I quickly set myself a goal: I wanted to promote the harp as a solo instrument, wherever and however I could. I wanted to do this not only through the performance of well-known pieces, but also by encouraging contemporary composers to produce new harp compositions. For my first Channel Classics CD, I have chosen a combination of three 20th-century French masters. The Parisian firm of Érard, in particular, created technical innovations to the harp which considerably broadened the instrument’s (chromatic) capabilities; these innovations, followed by the first ‘minor’ masterpieces by Debussy and Ravel, soon made Paris the epicentre of a veritable harp explosion. More and more well-trained harpists appeared, and so did composers who became interested in the harp. Even though André Caplet did not compose much for the harp, the ‘Deux Divertissements’ are now an indispensable part of the repertoire. They are one of the harpist’s ‘musts’. And I cannot imagine why Jacques Ibert’s ‘Six Pièces’, those surprisingly colourful miniatures – are so rarely performed in their entirety. French-American Carlos Salzedo occupies a special place in the world of the harp. Famous both as a performer and teacher, he was immensely influential. -

Klassieke Zaken Maart 2015

UITGAVE VAN DE VERENIGING KLASSIEKE ZAKEN 35STE JAARGANG MAART 2015 NR 2 BORODIN KWARTET 70 jaar Hét tijdschrift voor liefhebbers van klassieke muziek Carus is distributed in the Benelux by Outhere Distribution CAR83292 CAR83386 CAR83337 CAR83259 CAR83394 CAR83290 info: [email protected] EXCLUSIEVE AANBIEDING 23,99 * 15 ,99 EEN KWETSBARE SCHUMANN Robert Schumann is vooral de man van de piano. Zo wordt zijn pianoconcert nog geregeld uitgevoerd, maar zijn viool- en celloconcert behoren niet echt tot het stan- daard repertoire. Een doorn in het oog van het illustere trio Isabelle Faust, Jean-Guihen Queyras en Alexander Melnikov. Tijdens een tournee met een van de drie piano- trio’s op het programma besloten zij Schumann volledig te rehabiliteren met een trilogie: drie cd’s met elk een van de concerten gekoppeld aan een pianotrio. Deze eerste cd van het trio pleit meteen voor het gelijk van het drietal. Het Vioolconcert en het Derde pianotrio worden gespeeld op historische instrumenten en onthullen alles wat Schu- mann tot Schumann maakt. Heerlijke lyriek, soms aan waanzin grenzende dramatiek, en in alles prachtige mu- ziek die door de verfijnde klank van de darmsnaren en de schitterende begeleiding van het Freiburger Barockor- chester een prachtig breekbare intimiteit krijgt. Zo kwets- baar, open en eerlijk hoorde u Schumann nog nooit. ROBERT SCHUMANN TRILOGY VOL. 1 VIOLIN CONCERTO, PIANO TRIO NO. 3 Isabelle Faust, Jean-Guihen Queyras, Alexander Melnikov, Freiburger Barockorchester o.l.v. Pablo Heras-Casado FELIXFOTO: BROEDE HARMONIA MUNDI 3 14902 0219621 / 152 711 VKZ * Alleen verkrijgbaar bij de Klassieke Zaken Specialisten. Zie voor de complete lijst pagina 50. -

November 26, 2017

November 26, 2017: (Full-page version) Close Window “When you practice gratefulness, there is a sense of respect toward others.” — Dalai Lama Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Williams Dartmoor, 1912 ~ War Horse Clark/Recording Arts/Williams Sony Classical 37458 889853745821 Awake! 00:09 Buy Now! Paine Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 23 New York Philharmonic/Mehta New World Records 374 9322803742 00:48 Buy Now! Medtner Sonata-Idyll in G, Op. 56 Earl Wild Chesky AD1 01:01 Buy Now! Tower Made in America Nashville Symphony/Slatkin Naxos 8.559328 636943932827 01:16 Buy Now! Still Miniatures for Oboe, Flute and Piano Sierra Winds Cambria 1083 021475108329 Reference 01:29 Buy Now! Chadwick Aphrodite, a symphonic poem Czech State Philharmonic, Brno/Serebrier 2104 030911210427 Recordings 01:59 Buy Now! Harbach Demarest Suite London Philharmonic/Angus MSR Classics 1258 681585125823 02:11 Buy Now! Herrmann Suite ~ The Snows of Kilimanjaro Moscow Symphony/Stromberg Marco Polo 8.225168 636943516829 02:50 Buy Now! Barber Overture ~ The School For Scandal, Op. 5 Royal Scottish National Orchestra/Alsop Naxos 8.559024 636943902424 Concierto en Tango, for Cello and Orchestra, Op. Beau Fleuve 03:00 Buy Now! Aguila Mekinulov/Buffalo Philharmonic/Falletta 610708-094951 610708094951 110 Records 03:20 Buy Now! Hanson Rhythmic Variations on Two Ancient Hymns Nashville Symphony/Schermerhorn Naxos 8.559072 636943907221 CMS Studio 03:29 Buy Now! Beach Piano Quintet in F sharp minor, Op. 67 Escher String Quartet 82524 653738252427 Recordings Selections ~ Mountain Songs for Flute and Guitar (A 03:59 Buy Now! Beaser Glaser/Platino Koch International 7533 099923753322 Cycle of American Folk Music) 04:12 Buy Now! Mozart Violin Concerto No. -

Download Program Book

American Harp Society 2009 8TH SUMMER IN S T I TUTE 1 8 T H N AT I ONAL COMPET I T I ON A Revival of the Early Masters June 28 - July 2 Westminster Brigham Young College University Salt Lake City Provo UTAH American Harp Society 2009 8TH SUMMER IN S T I TUTE 1 8 T H N AT I ONAL COMPET I T I ON A Revival of the Early Masters EXPANDING TH E H A R P ’ S Re P E RTOIR E Lucy Scandrett AHS President Jan Bishop Conference Coordinator ShruDeLi Ownbey, David Day, Anamae Anderson Institute Coordinators June 28 - July 2 Westminster Brigham Young College University Salt Lake City Provo 1250 East 1700 South Harold B. Lee Library Salt Lake City, Utah 84105 Provo, Utah 84602 Acknowledgments We acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for the generous donation of their time, effort, and resources. Lyon & Healy Harps The welcome reception, competition harps, Lyon & Healy Awards, and technician Jason Azem Salvi Harps Competition harps Local AHS Chapter Refreshments for the Board of Directors, Executive Committee, competitors, and AHS Competition judges; flowers Lyon & Healy West Institute logo design, competition support, time Westminster College Jeff Brown Brigham Young University Website, all printed materials and graphics, recording events, ice cream bar and special events day, International Harp Archives expertise, program designer Lindsay Weaver Vanderbilt Music Company Sponsoring Sarah Bullen’s participation Anderson Insurance Two $1,000 scholarships Cherie Campbell Food coordinator Julie Keyes Volunteer coordinator Toni MacKay Registration -

CV July 2021:2

VINCENT DE KORT conductor Mariinsky Theatre, Bolshoi Theatre, Royal Swedish Opera, Semperoper Dresden, Oper Leipzig, New National Theatre Tokyo - Vincent de Kort is a regular guest conductor in many of the world’s leading opera houses and concert halls, collaborating with some of today’s most admired soloists and orchestras. He is known for his energetic conducting style, inspirational leadership and charismatic communication with musicians as well as audiences, across different nations and cultures. He developed a reputation as one of the finest Mozart conductors and has been widely respected for leading orchestras in period-style performances. Whilst his work previously maintained a focus on early music, de Kort is nowadays sought after for a wide repertoire, ranging from the classical and romantic period to world premieres across the globe. Orchestras De Kort has worked with many leading orchestras, including the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Staatskapelle Dresden, New Japan Philharmonic, Mariinsky Orchestra, Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestre Metropolitain de Montreal, Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Brussels Philharmonic, Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie, Magdeburgische Philharmonie, Bochumer Symphoniker, Brandenburger Symphoniker, Sinfonia Varsovia, Odense Symphony Orchestra, Sønderjyllands Symfoniorkester Berner Symfonieorchester, Luzerner Sinfonieorchester, Orchestre Symphonique de Tours, Hawaii Symphony Orchestra, Izmir State Symphony Orchestra, Palestine National Orchestra, European Sinfoniëtta, as well as the European Union -

Philip Glass' Days and Nights Festival Launches Streaming Portal Featuring Films of Landmark Performances

PHILIP GLASS’ DAYS AND NIGHTS FESTIVAL LAUNCHES STREAMING PORTAL FEATURING FILMS OF LANDMARK PERFORMANCES VISIONARY MODEL AIMS TO PROVIDE INCOME TO ARTISTS 10TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION OF FESTIVAL TO BE VIRTUAL IN 2021 Jerry Quickley performing Whistleblower at the 2014 Days and Nights Festival; Photo credit: Arturo Béjar February 4, 2021—The annual multidisciplinary Days and Nights Festival—which since 2011 has taken place in and around Big Sur, California and has brought together luminaries and pioneers in fields including music, dance, theater, literature, film and the sciences—launches today its premiere streaming portal featuring exclusive films of a selection of its landmark performances and events. Click HERE or visit PhilipGlassCenterPresents.org, and see below for upcoming film details and release dates. Conceived and developed by world-renowned American composer Philip Glass—who has taken part every year since inception—Days and Nights is designed to encompass arts of all disciplines and nurture them in a way that welcomes the future while exploring seminal developments throughout history. Key to that vision are collaborations between artists from across a broad range of disciplines, and the selection of films slated for release includes contributions by such wide-ranging figures as JoAnne Akalaitis, Tibetan artist Tenzin Choegyal, Danny Elfman, Molissa Fenley, María Irene Fornés, Allen Ginsberg, Dev Hynes (Blood Orange), Jerry Quickley and Glass himself. Featured performers and ensembles include Dennis Russell Davies, Ira Glass, Matt Haimovitz, Tara Hugo, Lavinia Meijer, Maki Namekawa, Gregory Purnhagen, Third Coast Percussion, Opera Parallèle and Glass and his Philip Glass Ensemble. See below for details. “From the beginning, I wanted it to be a cross-cultural festival, but not just in terms of musicians from different parts of the world. -

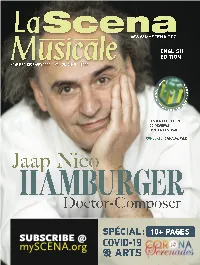

Myscena.Org Sm26-3 EN P02 ADS Classica Sm23-5 BI Pxx 2020-11-03 8:23 AM Page 1

SUBSCRIBE @ mySCENA.org sm26-3_EN_p02_ADS_classica_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 8:23 AM Page 1 From Beethoven to Bowie encore edition December 12 to 20 2020 indoor 15 concerts festivalclassica.com sm26-3_EN_p03_ADS_Ofra_LMMC_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 1:18 AM Page 1 e/th 129 saison/season 2020 /2021 Automne / Fall BLAKE POULIOT 15 nov. 2020 / Nov.ANNULÉ 15, 2020 violon / violin CANCELLED NEW ORFORD STRING QUARTET 6 déc. 2020 / Dec. 6, 2020 avec / with JAMES EHNES violon et alto / violin and viola CHARLES RICHARD HAMELIN Blake Pouliot James Ehnes Charles Richard Hamelin ©Jeff Fasano ©Benjamin Ealovega ©Elizabeth Delage piano COMPLET SOLD OUT LMMC 1980, rue Sherbrooke O. , Bureau 260 , Montréal H3H 1E8 514 932-6796 www.lmmc.ca [email protected] New Orford String Quartet©Sian Richards sm26-3_EN_p04_ADS_udm_OCM_effendi_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 8:28 AM Page 1 SEASON PRESENTER ORCHESTRE CLASSIQUE DE MONTRÉAL IN THE ABSENCE OF A LIVE CONCERT, GET THE LATEST 2019-2020 ALBUMS QUEBEC PREMIER FROM THE EFFENDI COLLECTION CHAMBER OPERA FOR OPTIMAL HOME LISTENING effendirecords.com NOV 20 & 21, 2020, 7:30 PM RAFAEL ZALDIVAR GENTIANE MG TRIO YVES LÉVEILLÉ HANDEL’S CONSECRATIONS WONDERLAND PHARE MESSIAH DEC 8, 2020, 7:30 PM Online broadcast: $15 SIMON LEGAULT AUGUSTE QUARTET SUPER NOVA 4 LIMINAL SPACES EXALTA CALMA 514 487-5190 | ORCHESTRE.CA THE FACULTY IS HERE FOR YOUR GOALS. musique.umontreal.ca sm26-3_EN_p05_ADS_LSM_subs_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 2:32 PM Page 1 ABONNEZ-VOUS! SUBSCRIBE NOW! Included English Translation Supplément de traduction française inclus -

190004325 Warchild NL DTD Magazine V7.Indd

THE DUTCH NATIONAL BALLET A NIGHT TO REMEMBER WHO INSPIRES SAM SMITH INTERVIEW WITH BRANDI CARLILE 01 FOREWORD INTRODUCING 02. MICHAELA’S VISITS TO HUMBERTO TAN UGANDA AND LEBANON 03. Your host of the night ABOUT WAR CHILD Humberto is a much-loved TV and radio presenter of Surinamese descent, best known for his presentation of RTL Late Night and 04. spots on RTL Boulevard, Studio Sport, Dance Dance Dance and MEET DANIEL - Holland’s Got Talent. For his work, he has won the Sonja Barend WAR CHILD Award and two times the Silver Televisier Star. FACILITATOR 05. 06 10 Wake up to the radio? ERNST SUUR - 15 YEARS DUTCH NATIONAL CHEFS & REFUGEE You might’ve caught Humberto brightening up your morning on ON THE FRONTLINE BALLET COMPANY Evers Staat Op or On the Move. Michaela is delighted to welcome him as your host for the event. 07. 11. SAM SMITH ADVISORY GROUP Did you know? Humberto was this year named Knight of the Order of Orange- 08. 12. Nassau. BRANDI CARLILE THANK YOU 09. MIA DEPRINCE & LAVINIA MEIJER 2 Foreword: Humberto Tan Voorwoord: HumbertoContent page Tan 3 PROGRAMME 6PM – RECEPTION & BITES — 7.15PM – OPENING Michaela DePrince & Humberto Tan — 7.45PM – A DREAM IS A SEED Michaela’s Story Yav - Christian Yav Latch - Sam Smith & Edo Wijnen — 8.20PM – A DREAM TAKES WORK I Am Enough - Daniel Montero Real & Band, Edo Wijnen & Nathan Brhane Interactive Session - Let’s draw Bubble of Time - Lavinia Meijer — 9.05PM – A DREAM AS ACHIEVEMENT Ocen Daniel Osako, War Child Facilitator Uganda The Joke – Brandi Carlile Party of One - Sam Smith & Brandi Carlile Auction – led by Paulina Cramer — 10.20PM – A DREAM TO SHARE 5 Tangos - Constantine Allen Embers - Nathan Brhane & Jessica Xuan Finale - Michaela & Mia DePrince — ‘TIL MIDNIGHT DJ Joshua Walters with vocals by Mavis Acquah 5 Dear friends, family, partners and colleagues… What a special moment this is. -

Radio 3 Listings for 15 – 21 May 2021 Page 1 Of

Radio 3 Listings for 15 – 21 May 2021 Page 1 of 11 SATURDAY 15 MAY 2021 Andante inédit in E flat major for piano Alpha: Alpha 725 Marc-Andre Hamelin (piano) https://outhere-music.com/en/albums/PH-Erlebach-Lieder- SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m000vzbw) ALPHA725 A piano recital given in Sweden by Claire Huangci 04:44 AM Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) Stravinsky: Le Sacre du Printemps & Eötvös: Alhambra American pianist Claire Huangci performs Scarlatti, Schubert, Andante Festivo for strings and timpani Concerto Rachmaninov, Brahms and Paderewski. Presented by John Danish Radio Concert Orchestra, Hannu Koivula (conductor) Isabelle Faust (violin) Shea. Orchestre de Paris 04:49 AM Pablo Heras-Casado (conductor) 01:01 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) https://www.harmoniamundi.com/#!/albums/2691 Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757) Nocturne in F minor, Op 55 no 1 Four Keyboard Sonatas (K.443, K.208, K.29, K.435) Shura Cherkassky (piano) 10.40am Conductor John Wilson on André Previn: Warner Claire Huangci (piano) Edition 04:54 AM 01:10 AM Flor Alpaerts (1876-1954) André Previn became a household name in the 60s and 70s and Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Capriccio - Luim (1953) was a prolific recording artist. Conductor John Wilson has been Piano Sonata no 20 in A, D.959 Flemish Radio Orchestra, Michel Tabachnik (conductor) immersed in a box set containing all of Previn's EMI and Claire Huangci (piano) Teldec recordings as both conductor and pianist. He shares his personal highlights in conversation with Andrew. 01:44 AM SAT 05:00 Piano Flow with Lianne La Havas (m000vzby) Sergey Rachmaninov (1873-1943) Vol. -

Digital Booklet Standard Master

LAVINIA MEIJER THE GLASS Digital Booklet Standard Master EFFECT THE Page Size: 11 x 8.264 inches (28 cm x 21 cm) MUSIC Four-page minimum Horizontal presentation O F All FONTS are embedded PHILIP RGB Color All images are full-bleed GLASS Final PDF must be no more the 10mb Your background artwork must fill until the red guide line - Bleed 0.125” (3.175mm). Do not place logos, text, or essential images outside of the white space Component 1 PHILIP GLASS Etudes (1994/2012) * 1 Etude No. 1 (6:27) 2 Etude No. 2 (6:54) 3 Etude No. 5 (8:10) 4 Etude No. 8 (5:05) 5 Etude No. 9 (3:28) 6 Etude No. 12 (7:34) 7 Etude No. 16 (5:21) 8 Etude No. 17 (8:03) 9 Etude No. 18 (6:21) Digital Booklet Standard Master10 Etude No. 20 (9:18) Component 2 PHILIP GLASS 1 Koyaanisqatsi (1982) (4:11) * Page Size: 11 x 8.264 inches (28 cm x 21 cm) BRYCE DESSNER Four-page minimum Suite for Harp (2016) 2 Movement I (3:59) Horizontal presentation 3 Movement II (1:28) ** All FONTS are embedded 4 Movement III (6:08) RGB Color NICO MUHLY 5 Quiet Music (2003) (3:54) * All images are full-bleed 6 A Hudson Cycle (2005) (2:55) * Final PDF must be no more the 10mb ÓLAFUR ARNALDS 7 Erla’s Waltz (2009) (1:54) 8 Tomorrow’s Song (2011) (3:06) Your background artwork must fill until the red NILS FRAHM 9 Ambre (2009) (3:51) * guide line - Bleed 0.125” (3.175mm). -

February 17, 2018

February 17, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “A designer knows he has achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.” — Antoine de Saint-Exupery Start Buy CD Stock Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Barcode Time online Number Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Corelli Concerto Grosso in C, Op. 6 No. 10 Southwest German Chmbr Orch/Wich Seraphim 69143 724356914322 Quartet in E flat for Piano and Strings, Op. 00:17 Buy Now! Beethoven Ax/Stern/Laredo/Ma Sony 53339 074645333922 16 00:44 Buy Now! Ravel Rapsodie espagnole French National Orchestra/Inbal Denon 1797 081759002804 Hahn/German Chamber Philharmonic of 01:01 Buy Now! Vieuxtemps Violin Concerto No. 4 in D minor, Op. 31 DG B0022698 028947939566 Bremen/P. Jarvi 01:33 Buy Now! Mendelssohn String Quintet No. 2 in B flat, Op. 87 L'Archibudelli Sony Classical 60766 074646076620 02:03 Buy Now! Boccherini Cello Concerto No. 10 in D Bylsma/Tafelmusik/Lamon DHM 7867 054727786723 02:22 Buy Now! Dessner Suite for Harp Lavinia Meijer Sony Classical 88985351432 889853514328 02:35 Buy Now! Delibes Suite ~ Coppelia Berlin Radio Symphony/Fricke LaserLight 15 616 018111561624 Courante ~ Cello Suite No. 6 in D, BWV 03:00 Buy Now! Bach Yo-Yo Ma Sony Classical 54723 886975472321 1012 Double Concerto for Violin & Cello in A 03:05 Buy Now! Brahms Mutter/Meneses/Berlin Philharmonic/Karajan DG 410 603 28941060327 minor, Op. 102 03:41 Buy Now! German Selections ~ Nell Gwyn Czecho-Slovak Radio Symphony/Leaper Marco Polo 8.223419 4891030234192 04:00 Buy Now! Nielsen Little Suite for Strings, Op.1 Academy of St. -

Jacobs School of Music BLOOMINGTON CAMPUS

jacobs school of music BLOOMINGTON CAMPUS www.music.indiana.edu Indiana University, a member of the North Central Association (NCA), is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission: www.ncahigherlearningcommission.org; (312) 263-0456. While every effort is made to provide accurate and current information, Indiana University reserves the right to change without notice statements in the bulletin series concerning rules, policies, fees, curricula, or other matters. BULLETIN 2007–2009 Administration Indiana University MICHAEL A. McROBBIE, Ph.D., President of the University CHARLES R. BANTZ, Ph.D., Executive Vice President and Chancellor, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis D. CRAIG BRATER, M.D., Vice President and Dean and Walter J. Daly Professor, School of Medicine J. TERRY CLAPACS, M.B.A., Vice President and Chief Administrative Officer DOROTHY J. FRAPWELL, J.D., Vice President and General Counsel THOMAS C. HEALY, Ph.D., Vice President for Government Relations CHARLIE NELMS, Ed.D., Vice President for Institutional Development and Student Affairs JUDITH G. PALMER, J.D., Vice President and Chief Financial Officer MICHAEL M. SAMPLE, B.A., Vice President for University Relations MARYFRANCES McCOURT, M.B.A., Treasurer of the University DAVID J. FULTON, Ph.D., Chancellor of Indiana University East MICHAEL A. WARTELL, Ph.D., Chancellor of Indiana University–Purdue University Fort Wayne RUTH J. PERSON, Ph.D., Chancellor of Indiana University Kokomo BRUCE W. BERGLAND, Ph.D., Chancellor of Indiana University Northwest UNA MAE RECK, Ph.D., Chancellor of Indiana University South Bend SANDRA R. PATTERSON-RANDLES, Ph.D., Chancellor of Indiana University Southeast KENNETH R. R. GROS LOUIS, Ph.D., University Chancellor Bloomington Campus JEANNE SEPT, Ph.D., Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Dean of the Faculties CHARLIE NELMS, Ed.D., Vice Chancellor for Academic Support and Diversity NEIL D.