Forest Stewardship Planning Workbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FSA1091 Basics of Heating with Firewood

DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE RESEARCH & EXTENSION Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Arkansas System FSA1091 Basics of Heating with Firewood Sammy Sadaka Introduction Many options of secure, wood combustion Ph.D., P.E. stoves, freplaces, furnaces and boilers Associate Professor Wood heating was the predominant are available in the market. EPA certifed freplaces, furnaces and wood stoves with Extension Engineer means for heating in homes and businesses for several decades until the advent of no visible smoke and 90 percent less iron radiators, forced air furnaces and pollution are among alternatives. Addi- John W. Magugu, Ph.D. improved stoves. More recently, a census tionally, wood fuel users should adhere Professional Assistant by Energy Information Administration, to sustainable wood management and EIA, has placed fuelwood users in the environmental sustainability frameworks. USA at 2.5 million as of 2012. Burning wood has been more common Despite the widespread use of cen- among rural families compared to families tral heating systems, many Arkansans within urban jurisdictions. Burning wood still have freplaces in their homes, with has been further incentivized by more many others actively using wood heating extended utility (power) outages caused systems. A considerable number of by wind, ice and snowstorms. Furthermore, Arkansans tend to depend on wood fuel liquefed petroleum gas, their alternative as a primary source of heating due to fuel, has seen price increases over recent high-energy costs, the existence of high- years. effciency heating apparatuses and Numerous consumers continue to have extended power outages in rural areas. questions related to the use of frewood. An Apart from the usual open freplaces, important question is what type of wood more effcient wood stoves, freplace can be burned for frewood? How to store inserts and furnaces have emerged. -

Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual

PB 1854 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual 1 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual Contributing Authors Alan B. Galloway Area Farm Management Specialist [email protected] Megan Bruch Leffew Marketing Specialist [email protected] Dr. David Mercker Extension Forestry Specialist [email protected] Foreword The authors are indebted to the author of the original Production of Christmas Trees in Tennessee (Bulletin 641, 1984) manual by Dr. Eyvind Thor. His efforts in promoting and educating growers about Christmas tree production in Tennessee led to the success of many farms and helped the industry expand. This publication builds on the base of information from the original manual. The authors appreciate the encouragement, input and guidance from the members of the Tennessee Christmas Tree Growers Association with a special thank you to Joe Steiner who provided his farm schedule as a guide for Chapter 6. The development and printing of this manual were made possible in part by a USDA specialty crop block grant administered through the Tennessee Department of Agriculture. The authors thank the peer review team of Dr. Margarita Velandia, Dr. Wayne Clatterbuck and Kevin Ferguson for their keen eyes and great suggestions. While this manual is directed more toward new or potential choose-and-cut growers, it should provide useful information for growers of all experience levels and farm sizes. Parts of the information presented will become outdated. It is recommended that prospective growers seek additional information from their local University of Tennessee Extension office and from other Christmas tree growers. 2 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual Contents Chapter 1: Beginning the Planning ............................................................................................... -

Do-It-Yourself Ways to Steward a Healthy, Beautiful Forest | Northwest Natural Resource Group | Take the Time to Become Familiar with Your Forest

You can do many simple things yourself to make your forest attract more wildlife, provide recreation, and contribute to its own upkeep. Our forests provide for us in many ways. Their While getting to know your forest, you can do a lot beauty inspires us. They clean the air, filter and store to improve its health and enhance its beauty. water, protect soil, and shelter diverse plants and wildlife. They sustain livelihoods and yield firewood, This guide focuses on common ways Northwest building materials, and edible and forest owners can steward their land to meet a range of goals. These practices include: medicinal plants. With all that forests do for us, a little care in Observing and monitoring the forest return will help our forests Making your forest more wildlife-friendly continue to sustain our well-being. Controlling invasive plants Keeping soil fertile and productive This guide is intended for forest Creating structural and biological diversity owners who are just getting started in stewarding their land. This is not an exhaustive manual with detailed NNRG put this information together based on years instructions on how to complete these DIY of experience working with families, small businesses, practices. Instead, it describes the most important and conservation groups across western Oregon and actions to help you start your journey of forest Washington. In conducting site visits, we’ve found stewardship. At the end of this booklet, you’ll find a that lands share common needs and owners share list of resources that can help you learn how common questions. to carry out each of these practices. -

GMF99001 GMF99001 Eandr.Pdf

ERMA New Zealand Evaluation & Review Report Application for approval to field test in containment genetically modified radiata pine (Pinus radiata D.Don) and Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst) Application Numbers: GMF99001 and GMF99005 Prepared for the Environmental Risk Management Authority Page 2 of 152 October 2000 ERMA New Zealand Evaluation & Review Report: GMF99001 & GMF99005 Application for approval to field test in containment genetically modified radiata pine and Norway spruce Key Issues In evaluating the risks, costs and benefits associated with these applications, ERMA New Zealand has identified the following key issues: The length of the field trial The proposed field trials will last for up to 20 years, although individual trees will only be grown in the trial site for between three and ten years. The genetically modified trees will not be grown for the normal duration that can be expected in a commercial plantation. Consequently, the proposed field trials will not provide an opportunity for complete evaluation of the genetically modified trees over their expected life span. Pollen escape The most important risks with this application are those associated with the possible escape of pollen. Unless very strict containment is maintained, it would be prudent to assume that there are significant risks from cross pollination with trees outside of the trial. The risk is compounded from two factors. The first is the long duration of the trial (20 years) with the increased number of opportunities this represents for the inadvertent development and release of pollen. ERMA New Zealand considers that it is likely that some pollen may be inadvertently shed during the trials due to reproductive structures not being removed (either by being missed or not being recognised) prior to maturity. -

FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES

FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES FORESTS and GENETICALLY MODIFIED TREES FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2010 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. All rights reserved. FAO encourages the reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. © FAO 2010 iii Contents Foreword iv Contributors vi Acronyms ix Part 1. THE SCIENCE OF GENETIC MODIFICATION IN FOREST TREES 1. Genetic modification as a component of forest biotechnology 3 C. -

A Glossary of Common Forestry Terms

W 428 A Glossary of Common Forestry Terms A Glossary of Common Forestry Terms David Mercker, Extension Forester University of Tennessee acre artificial regeneration A land area of 43,560 square feet. An acre can take any shape. If square in shape, it would measure Revegetating an area by planting seedlings or approximately 209 feet per side. broadcasting seeds rather than allowing for natural regeneration. advance reproduction aspect Young trees that are already established in the understory before a timber harvest. The compass direction that a forest slope faces. afforestation bareroot seedlings Establishing a new forest onto land that was formerly Small seedlings that are nursery grown and then lifted not forested; for instance, converting row crop land without having the soil attached. into a forest plantation. AGE CLASS (Cohort) The intervals into which the range of tree ages are grouped, originating from a natural event or human- induced activity. even-aged A stand in which little difference in age class exists among the majority of the trees, normally no more than 20 percent of the final rotation age. uneven-aged A stand with significant differences in tree age classes, usually three or more, and can be basal area (BA) either uniformly mixed or mixed in small groups. A measurement used to help estimate forest stocking. Basal area is the cross-sectional surface area (in two-aged square feet) of a standing tree’s bole measured at breast height (4.5 feet above ground). The basal area A stand having two distinct age classes, each of a tree 14 inches in diameter at breast height (DBH) having originated from separate events is approximately 1 square foot, while an 8-inch DBH or disturbances. -

Silviculture Art & Science of Establishing & Tending Trees & Forests

Silviculture Art & science of establishing & tending trees & forests Karen Bennett, Extension Forestry Professor & Specialist Presented to NH Coverts, September 2010 Silviculture Actions Have Two Broad Outcomes • Grow the trees that are already present –tending • Start new trees – regenerate • In practice, often accomplish both outcomes at once • Most common actions- cut trees or leave trees 1 Forest Management/ Forest Stewardship Interaction of silviculture, ecology, landowner objectives, multiple resources, economics, marketing, regulation, societies’ needs and interests and time. – Markets, plans, laws, harvesting, equipment, landowner, logger, forester, neighbors, trails, access Silviculture is the set of site specific tools used in forest management – weeding, thinning, pruning, improving, harvesting, regenerating, uneven age, even age, selection, shelterwood, clearcut The Forest Management Triangle For Success Landowner Logger Forester 2 Hallmarks of Good Forest Stewardship/ Management • Considers multiple resources • Based on landowner objectives • Uses best available practices • Practices based on a plan • Looks long term • Uses professionals • Uses best available science- SILVICULTURE Commercial timber harvesting is the most common tool for managing forested habitats Commercial timber harvesting: Trees are cut (“harvested”) and sold as lumber, pulp, biomass, firewood Ability of landowners to manage forested habitats is largely dependent on their ability to sell forest products from their land! Timber harvesting can alter Though -

FOREST MANAGEMENT 101 a Handbook to Forest Management in the North Central Region

FOREST MANAGEMENT 101 A handbook to forest management in the North Central Region This guide is also available online at: http://ncrs.fs.fed.us/fmg/nfgm A cooperative project of: North Central Research Station Northeastern Area State & Private Forestry Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota Silviculture 21 Silviculture Silviculture The key to effective forest management planning is determining a silvicultural system. A silvicultural system is the collection of treatments to be applied over the life of a stand. These systems are typically described by the method of harvest and regeneration employed. In general these systems are: Clearcutting - The entire stand is cut at one time and naturally or artificially regenerate. Clearcutting Seed-tree - Like clearcutting, but with some larger or mature trees left to provide seed for establishing a new stand. Seed trees may be removed at a later date. Seed-tree 22 Silviculture Shelterwood - Partial harvesting that allows new stems to grow up under an overstory of maturing trees. The shelterwood may be removed at a later date (e.g., 5 to 10 years). Shelterwood Selection - Individual or groups of trees are harvested to make space for natural regeneration. Single tree selection 23 Silviculture Group tree selection Clearcutting, seed-tree, and shelterwood systems produce forests of primarily one age class (assuming seed trees and shelterwood trees are eventually removed) and are commonly referred to as even-aged management. Selection systems produce forests of several to many age classes and are commonly referred to as uneven-aged management. However, in reality, the entire silvicultural system may be more complicated and involve a number of silvicultural treatments such as site preparation, weeding and cleaning, pre-commercial thinning, commercial thinning, pruning, etc. -

Healthy Forests for Clean Water

HEALTHY FORESTS FOR CLEAN WATER Did You Know? We all need clean water to stay healthy, yet less than one percent of the water on earth can be used by humans as drinking water. Whether you drink water from a well or a municipal supply, forests keep that water clean and abundant. They do this by capturing rainwater and recharging underground aquifers. They also act as a natural filter as water moves over land, cleaning it of pollutants so it arrives at our lakes, rivers and streams in a better condition. We call this an ecosystem service — something our environment provides that people need, but don’t Green Swamp. Photo Credit: Misty Buchanan have to pay for. Rainfall runoff that flows over parking lots and roads also picks up oil, grease, trash or other pollutants. Natural Water Filter This rainfall runoff then flows into stormdrains that Forests act as a natural water filter. When it rains, flush the water directly to the stream, river or lake it any water that does not soak into the ground drains to, without any treatment. But healthy becomes runoff and travels downslope to the closest forests, especially when properly managed and stream, river or lake. As runoff travels it picks up maintained, catch this runoff, slow its speed and nutrients from excess fertilizer and animal waste allow pollutants to settle out. The trees in the forests carrying that nutrient pollution into our waters, which also absorb some of the heavy metals, chemicals, is mainly nitrogen and phosphorus. All plants, and oil that come off pavement and other surfaces. -

Logging Safety: a Field Guide

LOGGING SAFETY: A FIELD GUIDE New York Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation Program New York State Department of Health Introduction Logging has consistently been one of the most hazardous industries in the United States. • 95 workers were fatally injured in the U.S. logging industry in 2006, resulting in a fatality rate of 85.6 deaths per 100,000 workers. The fatality rate for all occupations in the U.S. in 2006 was 4.0 deaths per 100,000 workers. • 40 workers were killed in New York State while performing tree work, including logging, between 20022007. • 17% of logging employee fatalities are machine related accidents. • 40,000 logging injuries occurred in the U.S. in 2007. Total medical costs approached $300 million. The information in this booklet reviews the key elements of logging hazards and the OSHA Logging Standard requirements and suggests some preventive measures that can help loggers and other tree workers to reduce injuries and work safely. 1 Table of Contents SECTION ONE: Logging Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) . 3 SECTION TWO: Chain Saw Safety . 12 SECTION THREE: Manual Felling . 19 SECTION FOUR: Limbing and Bucking. 35 SECTION FIVE: Skidding/Yarding . 45 SECTION SIX: Loading and Transporting. 48 SECTION SEVEN: Machines and Vehicles . 52 SECTION EIGHT: Chemicals. 64 SECTION NINE: Signaling and Signal Equipment. 66 SECTION TEN: First Aid and Emergencies . 67 SECTION ELEVEN: Logging Safety Program. 80 APPENDIX: Glossary of Logging Terms. 96 Acknowledgments . 107 2 SECTION ONE 1 Logging Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) L o g g i n g • Use to protect the head, ears, eyes, P e r face, hands, legs and feet. -

DO's and DON'ts in Pruning

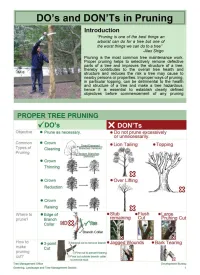

DO's and DON'Ts in Pruning Introduction "Pruning is one of the best things an arborist can do for a tree but one of the worst things we can do to a tree" -Alex Shigo Pruning is the most common tree maintenance work. Proper pruning helps to selectively remove defective parts of a tree and improves the structure of a tree, thereby contributes to the overall tree health and structure and reduces the risk a tree may cause to nearby persons or properties. Improper ways of pruning, in particular topping, can be detrimental to the health and structure of a tree and make a tree hazardous, hence it is essential to establish clearly defined objectives before commencement of any pruning PROPER TREE PRUNING V"DO's X DON'Ts Objective • Prune as necessary. • Do not prune ~xcessively or unnecessanly. Common • Crown ,../·'\ (;· - · Dead/Diseased • Lion Tailing •Topping Types of Cleaning r ·"· , •. ~ Branches (remove) .~ ~ Pruning Z-,/ - : ..... Broken Branches (remove) • Crown Thinning • Crown • Over Lifting Reduction • Crown Raising ~ Where to • Edge of •Flush prune? Branch Cut Cut Collar How to • 3-point unds • Bark Tearing make Cut pruning cut to prevent tearing cut? Tree Management Office Development Bureau Greening, Landscape and Tree Management Section 1 How much to prune? In general, pruning of large/mature trees should be avoided as far as practicable. No more than 25°/o of the live crown should be removed in any one year even for young trees. Common Types of Pruning ../ Crown Cleaning Dead/Diseased Branches (remove) Definition: Crown cleaning consists of selective removal of dead, dying, diseased and weak branches from a ;;I tree's crown. -

The Stoddard-Neel Approach to Ecological Forestry in Longleaf Pine Grasslands Graphic Design by Lenz | Decatur, Georgia

Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center he Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center at Ichauway seeks to understand, to demonstrate Tand to promote excellence in natural resource management and conservation on the landscape of the southeastern Coastal Plain of the United States. The Jones Center was founded on a long-standing ethic of conserving land and water resources. Ichauway is maintained as the tangible expression of this natural resource management philosophy. Central to this philosophy is the conviction that management and research inform each other and are partners in their contribution to knowledge. One of the Jones Center’s most important products is people who combine a rigorous understanding of ecological principles with proficiency in natural resource management. To understand the natural systems of the southeastern Coastal Plain, the Jones Center assembles information from respected practitioners and scientific literature and conducts targeted research to expand the knowledge of the field. Through a rigorous and creative research program, the Jones Center aspires to improve management and stewardship of regional resources and contribute to natural resource science at the national and international levels. To demonstrate excellence in natural resource management, the Jones Center manages Ichauway to protect and enhance the diversity of natural communities and their component species. The practical and economic aspects of proper stewardship are fundamental considerations of our work. To promote excellence in natural resource management and conservation, the Center develops and conducts education and outreach programs for undergraduate and graduate students, interns and landowners and managers. The Jones Center serves as a science-based resource for public officials, policymakers and the public.