David J. Walker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Modern Coach Is

Commander-in-chiefthe modern coach is ot for the first club,” said North Melbourne staff, the media and, through implementation of different the performance of all our One minute it is about a intoned with sharp directness if The demands of modern time, the concept coach Brad Scott, who has the media, supporters to impress systems or structures to make staff,” Scott said. player’s living arrangements, anyone stepped over the mark. coaching are becoming of the coach been in the job two years, after along the way. sure things are geared around “To be able to do that, the next training loads are being What such a system allowed more complex than ever. in the modern an apprenticeship as Mick No wonder effective senior working towards that vision.” I need to have relevant discussed. Then the president was for people to flourish As the face and leader game needs Malthouse’s development and coaches are now up there with The coach is pivotal in setting qualifications and at least a base is on the phone, then there is within their area of expertise— of the club, the role is explaining. assistant coach at Collingwood. the best and the brightest in that direction, but he does not level of understanding in all the team meeting detailing whether as an assistant coach, As the role has become What clubs need now more the community. work in isolation. The club’s those areas.” systems for the a physiotherapist, sports all-encompassing. N scientist, doctor or information more complicated, the gap than ever is a coach-manager, “The tactical side of things system must work to support It is hard game ahead, PETER RYAN between what the talkback set someone with a skill set akin to and actual football planning is the football department’s vision to imagine and then the technology manager—without imagines clubs require and what that of any modern executive potentially the easiest thing,” so the club CEO, the board Jock McHale list manager over-reaching it. -

Geelong Falcons Football Club Sponsors

PREMIERS 1992 & 2000 RUNNERS UP 1994 & 1998 PRELIMINARY FINALISTS 1996 / 2009 FINALISTS 1993 / 1995 / 1999 / 2001 / 2003 / 2004 / 2005 / 2006 / 2007 / 2008 / 2010 AFL VICTORIA TAC CUP 2010 ANNUAL REPORT Major Sponsor: 2004 – 2010 Rex Gorell Ford has completed 7 years as the Geelong Falcons major sponsor. The terms of the sponsorship, providing a car for the Falcons, have proved most beneficial to date for all concerned. Major Sponsor AFL Victoria TAC Cup - SPONSORS The Geelong Falcons Football Club thank and acknowledge the support and sponsorship of the following group of companies: SPONSOR OF THE AFL VICTORIA-TAC CUP T.A.C. – GEELONG FALCONS FOOTBALL CLUB SPONSORS Major Sponsor: REX GORELL FORD - Premier Sponsors: PIZZA HUT QEST ROSS PARKE – THE GOOD GUYS SUBWAY WERRIBEE FOOTBALL CLUB Corporate Sponsors: BRIAN ANDREW - MASTER BUILDER BUCKLEY‟S ENTERTAINMENT CENTRE GLYNN HARVEY FRUIT & VEGETABLES McHARRY‟S BUSLINES RODPAK – WERRIBEE Gold Sponsors: BELMONT STEREO SYSTEMS BRUMBY‟S BUXTON REAL ESTATE CHILWELL OFFICE SUPPLIES DEGRANDI CYCLE & SPORT FAGGS MITRE 10 GEELONG AQUATIC CENTRE GRAND HYATT, MELBOURNE MR COOL ICE WESTCOAST TRAILERS PROMOTE-IT TROPHY & CLOTHING COMPANY Player Sponsors: ANDREW RUSSELL EXCAVATIONS – Darcy Williamson BELLARINE SMASH REPAIRS – Thomas Ruggles DARRIWILL FARM – Andrew Boseley DEAN McFARLANE WELDING – Luke Dahlhaus FRESHWATER FINE FOODS – Kieran Paliouras HIGHWAY LOUNGE WERRIBEE – Jordan Keras JETSET WAURN PONDS – Jacob Welsh MEGATIX – Joshua Walker MORGAN ELECTRICS & GAS – David Peel SERVICE STREAM COMMUNICATIONS – Jai Sheahan SNACK FOOD INTERNATIONAL – Daniel Semmens WATHAURONG ABORIGINAL CO-OPERATIVE LTD – Lachlan Edwards Photographs supplied by Lindsay Addison Photography, Brian Bartlett et al INTRODUCTION AFL VICTORIA TAC CUP & AFL VICTORIA DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS GEELONG FALCONS: With the expansion of the Victorian Football League to the Australian Football League, a junior structure known as the Victorian State Football League was established in 1992. -

The Sport Stamps of Australia

Issue: 3:2008 Philatelic Review Bulletin Penrith & District Philatelic Society P.O. Box 393 Kingswood NSW 2747 This bulletin is protected by copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries concerning publication, translation or recording rights should be address to the Penrith & District Philatelic Society Produced in Australia by Penrith & District Philatelic Society P.O. Box 169 Penrith NSW 2750 Edited Uwe Krüger President [email protected] [email protected] 2 Dear members and collectors, Meetings The contents of this bulletin aims at informing Start: 8:00 pm; first Thursday in the month (except members of pending auctions, stamps issues and January) other calendar items relevant to our hobby. CWA Rooms, Baby Health Centre, Tindale Street, As things go, there will be room for errors but I Penrith hope I can keep those to a minimum. The editor Date Activity 1 May 2008 Exhibition; Trading Contents 5 June 2008 Election Meetings ................................................................ 3 3 July 2008 Exhibition; Trading References ............................................................. 3 Club Pack Auction Events .................................................................... 4 7 August 2008 Exhibition; Trading APTA ................................................................ 5 4 September 2008 Exhibition; Trading Auctions ............................................................... -

Geelong Falcons

GEELONG FALCONS FOOTBALL CLUB PREMIERS 1992, 2000 & 2017 RUNNERS UP 1994 & 1998 PRELIMINARY FINALISTS 1996 / 2009 / 2013 / 2016 FINALISTS 1993 / 1995 / 1999 / 2001 / 2003 / 2004 / 2005 / 2006 / 2007 / 2008 / 2010 / 2011 / 2012 / 2014 / 2015 AFL VICTORIA TAC CUP 2017 ANNUAL REPORT #Selfless #Resilient #Accountable 2017 TAC Cup Premiers! Major Sponsor: 2004 – 2017 Rex Gorell Ford has completed 14 years as the Geelong Falcons major sponsor. The terms of the sponsorship, providing a car for the Falcons, have proved most beneficial to date for all concerned. Major Sponsor AFL Victoria TAC Cup - SPONSORS The Geelong Falcons FC would like to thank and acknowledge the support & sponsorship of the following: SPONSOR OF THE AFL VICTORIA - TAC CUP - TAC: “Towards Zero” Geelong Falcons’ Sponsors – Season 2017 Major Sponsor: Premier Sponsors: Andrew Katos, MP Level 1, 174-178 Torquay Road, GROVEDALE VIC 3216 Corporate Sponsors: Ph: (03) 5243 5222 Gold Sponsors: The Cremorne Hotel 336 Pakington Street, NEWTOWN VIC 3220 Ph: (03) 5221 2702 Player Sponsors • Autosales Australia – Brayden Ham • King Island Fisheries Pty Ltd – Cooper Stephens • AUS DENT – Titit Nyak • MCG International – Doyle Madigan • Clarke & Co. Builders – Gryan Miers • Morlo's Bricklaying – David Handley • Create on Ormond – Peterson Kol • Surfcoast Peachy Cleaning – Mitchell Chafer • Forms Express – Colm O’Connor • TWP Plastering – Lachlan Handley • Harry's Kiosk – Charlie Francis • Williams Village Investments – Ethan Floyd Photographs supplied by Brian Bartlett INTRODUCTION AFL VICTORIA TAC CUP & AFL VICTORIA DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS GEELONG FALCONS With the expansion of the Victorian Football League to the Australian Football League, a junior structure known as the Victorian State Football League was established in 1992. -

The Port Adelaide Football Club Thanks the Following Companies for Their Support in 2007 JOINT MAJOR SPONSORS

07 ANNUAL REPORT NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Confirmation is hereby given that the Annual General Meeting of the Port Adelaide Football Club will be held at 7.00pm on Monday 17 December 2007, in the upstairs Members’ area of The Port Club at Alberton Oval, Queen Street, Alberton. Nominations were previously advertised for the Board of Directors (2) in the Notice of the AGM (Advertiser 3/11/07) and the following nominations have been received: POSITIONS REQUIRED – 2 Candidates - Existing Board Member(s):- Mr Max James (not seeking re-election) Mr Frank Hayter (not seeking re-election) Additional Nominations:- Mr David Coluccio Mr Anthony Toop Mr Darryl Wakelin Mr Nick Williamson Postal voting only will apply and voting forms with reply paid envelopes are enclosed with this Annual Report. Postal votes must be in the hands of the returning officer by 5pm on Friday, 14 December 2007. BUSINESS 1. Receive Reports To table, consider, and receive:- (a) The Directors’ Statement and Report in respect to the consolidated entity for the financial year ended 31 October 2007. (b) The financial accounts of the consolidated entity prepared in respect of the year ended 31 October 2007. (c) The auditor’s report in respect to the consolidated entity’s financial accounts for the year ended 31 October 2007. 2. Result of voting for Club elected Directors (2) 3. To transact any other business as shall lawfully be brought before the meeting 4. To provide information to Members on Club progress and preparedness for the 2008 season • Mark Williams – 2007/08 season • Introduction – New Players By order of the Board J.M. -

TAC Record Rnd 11.Indd

TAC CUP ROUND 11 JUNE 29-30, 2013 $3.00 KKnightsnights mmarcharch iintonto ttopop eeightight Team of the First 21 Years FB: Simon Beaumont FB: Jason Blake FB: Simon Garlick HB: Tom Murphy HB: Ted Richards HB: Danny Jacobs F: Robert Warnock F: Chris Judd C: Jason Cripps C: Justin Murphy F: Luke Ball C: Jobe Watson HF: Aaron Lord HF: Tom Hawkins HF: Josh Kennedy FF: Stephen Powell FF: Chris Dawes FF: Matthew Robbins INT: Jackson Sketcher INT: Carl Steinfort INT: Scott Thornton INT: David Gallagher INT: Shane Valenti GGeelongeelong FFalconsalcons 110.7.670.7.67 d WWesternestern JJetsets 99.10.64.10.64 Photos: Brian Bartlett AFL VICTORIA CORPORATE PARTNERS NAMING RIGHTS PREMIER PARTNERS OFFICIAL PARTNERS APPROVED LICENSEES EDITORIAL TAC Cup regions celebrate their history, 21 years on One of Australia’s premier sporting competitions’ short but that grow up in Victoria, to rich history has been rediscovered with the Sandringham be exposed to a program Dragons and Geelong Falcons’ 21 year celebrations over that is not far from AFL recent weeks. level is great,” Judd said. Well over one hundred current and former Dragons players At the Falcons’ recent 1992 and staff fi lled Trevor Barker Oval’s function room last premiership reunion, Sunday night to celebrate the club’s ‘Best Team Ever’ ruckman and now Gold Chris Judd with Ian Kyte at the Sandringham function presentation. Coast Suns assistant coach Carlton champion Chris Judd was drafted from Matthew Primus also noted the TAC Cup’s progression. Sandringham with the third selection of the 2001 NAB AFL “The competition has evolved - TAC Cup clubs are doing a Draft and was named alongside Collingwood’s Luke Ball as lot of the same things as AFL clubs, with the level of one of the Dragons’ greatest on-ballers. -

Your Next Move Is to Ring Avis!

Saturday & Sunday $2.00 June 28 & 29, 2003 Vol. 7 • No. 11 ' Move the Family! • I Move the Team! I ,.,..• AVIS • , I _ Move the House! Your next move is to ring Avis! WettJ. harder. 97 Edward Street Wagga Wagga Proud major sponsor of Southern NSW / Wagga Territory Manager Tel : (02) 6921 9977 Murrumbidgee Valley Australian Football Tony Quinn Fax: (02) 6921 7278 Association Inc. 0408 693 582 ~ Frequent.flyer Printed by Oxford Printery. Wagga Wagga. Ph 6921 3196. Fax 6921 8161. Email: [email protected] -for the M.V.A.F.A. Inc. ~VaHeyAu>IFoOlb,,IAs,oc nc • "FOOTYAECOAD" - 2003 Mu1rumbdgee Valley it.us!._ Footllall -'SSOC Inc O ~FOOTY RECORD~- 2003 RIVERINA FOOTBALL LEAGUE LADDERS 2003 somewhat shaky. Leeton were pretty good last week even though being defeated by Turvey it FIRST GRADE LADDER Country Energy U18s LADDER 1 wasn't by a big margin. Scott Allen, Brad Sandbrook and the Balding Bros will be keys for Round 10 w L D For Ag % Pts Round 10 w L D For Ag 0 • Pts EOitorial Mango whilst David Kidman. Jamie Broadbent and TU9VEY PARK 9 1245 627 198.56 36 TURVEY PARK' 8 1 990 376 263.30 36 ROUND11 Brad Waters are important players in the Crows COOLAMON 8 2 1198 805 148.82 32 MAN.-C-U-E' 7 2 765 501 152.69 32 chances of victory. Visiting Clubs usually struggle GRIFFITH 7 3 1205 761 158.34 28 COO LAMON' 4 4 669 490 136.53 24 Wonders never cease wilh 100% in the tipping at Leeton and I think that Mango will do just that arena last week. -

2008 Yearbook Port Adelaide Football Club

14 28 54 Contents 2008 Yearbook Port Adelaide Football Club 2 PRESIDENT’S REPORT 34 KANE’S COMING OF AGE Greg Boulton Best & Fairest wrap 4 MEET THE BOARD 42 PLAYER REVIEWS 2008 Board of Directors Analysis of every player INTRODUCING OUR ALLAN SCOTT AO, OAM Cover: 2008 John Cahill Medallist 5 47 Kane Cornes. Read more about NEW PRESIDENT Giving thanks to Allan Scott Kane’s Coming of Age on page 34. Q & A with Brett Duncanson ROBERT BERRIMA QUINN Cover design: EnvyUs Design 48 Cover photography: AFL Photos 7 CEO’S REPORT Paying homage to one of Power Brand Manager: Jehad Ali Mark Haysman our all time greats Port Adelaide Football Club Ltd COACH’S REPORT THE COMMUNITY CLUB 10 50 Brougham Place Alberton SA 5014 Mark Williams The Power in the community Postal Adress: PO Box 379 Port Adelaide SA 5015 Phone: 08 8447 4044 Fax: 08 8447 8633 ROUND BY ROUND CLUB RECORDS 14 54 [email protected] PortAdelaideFC.com.au 2008 Season Review 1870-2008 Design & Print by Lane Print & Post Pty Ltd NEW LOOK FOR ‘09 SANFL/AFL HONOUR ROLL 22 60 101 Mooringe Avenue Camden Park SA 5038 Membership Strategy 1870-2008 Phone: 08 8179 9900 Fax: 08 8376 1044 25 ALL THE STATS 62 STAFF LIST [email protected] LanePrint.com.au Every player’s numbers 2008 Board, management Yearbook 2008 is an offi cial publication from 2008 staff and support staff list of the Port Adelaide Football Club President Greg Boulton 26 2008 PLAYER LIST 64 LIFE MEMBERS Chief Executive Mark Haysman Games played for 2008 1909-2008 Editors Daniel Norton, Andrew Fuss Writers Daniel Bryant, Andrew Fuss, Daniel Norton 28 OUR HEART AND SOUL THE NUMBERS Photography AFL Photos, Gainsborough Studios, A tribute to Michael Wilson PAFC FINANCIALS FOR 2008 Bryan Charlton, The Advertiser 65 -Notice of AGM THANKS FOR THE MEMORIES 30 - Directors’ Report Copyright of this publication belongs to the Port Adelaide Football Club Ltd. -

Single File 4 Print

PREMIERS 1992 & 2000 RUNNERS UP 1994 & 1998 FINALISTS 1993 / 1995 / 1996 / 1999 2001 / 2003 / 2004 / 2005 / 2006 FOOTBA LL VICTORIA TAC CUP 2006 ANNUAL REPORT MAJOR SPONSOR: 2004 – 2006 Rex Gorell Ford, in conjunction with Ford Credit, have completed their first 3 years as the Geelong Falcons major sponsor. The terms of the sponsorship, providing a car for the Falcons, have proved most beneficial to date for all concerned. Major Sponsor Football Victoria TAC Cup - SPONSORS The Geelong Falcons Football Club would like to thank and acknowledge the support and sponsorship of the following group of companies: SPONSOR OF THE FOOTBALL VICTORIA-TAC CUP TAC – GEELONG FALCONS FOOTBALL CLUB SPONSORS Major Sponsor: REX GORELL FORD – FORD CREDIT Premier Sponsor: SUBWAY Corporate Sponsors: McHARRY’S BUSLINES GLYNN HARVEY FRUIT & VEGETABLES RODPAK - WERRIBEE KARDINIA CAFÉ BUCKLEY’S ENTERTAINMENT CENTRE ALLFORKS CAT- FORKLIFTS Gold Sponsors: BELMONT STEREO SYSTEMS BRIAN ANDREW - MASTER BUILDER CHILWELL OFFICE SUPPLIES CRAWLEYS TAKEAWAY – TERANG DEGRANDI CYCLE & SPORT FAGGS MITRE 10 PROMOTE-IT TROPHY & CLOTHING COMPANY ROCOCO HAIRDRESSING ROWICK PRINTERS VILLAGE CINEMAS WESTCOAST TRAILERS Photographs supplied by Lindsay Addison Photography INTRODUCTION FOOTBALL VICTORIA T.A.C. CUP & FV DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS GEELONG FALCONS: With the expansion of the Victorian Football League to the Australian Football League, a junior structure known as the Victorian State Football League was established in 1992. Commencing with 6 Metropolitan based teams, including the Geelong Falcons , i t was expanded to a 12 team competition incorporating 7 Metropolitan based teams and 5 regional based teams (Ballarat Rebels , Bendigo Pioneers , Geelong Falcons , Gippsland Power and Murray Bushrangers ), before the addition of 2 Interstate based teams (NSW/ACT Rams and Tasmanian Tassie Mariners ) in 1996 which took the competition to a 14 team structure. -

Australian Football League

AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE ANNUAL REPORT 2014 CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE 118th ANNUAL REPORT 2014 4 2014 HIGHLIGHTS 18 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 28 CEO’S REPORT 35 BROADCASTING, SCHEDULING & INFRASTRUCTURE 45 FOOTBALL OPERATIONS 65 COMMERCIAL OPERATIONS 83 AFL MEDIA 87 PEOPLE, CULTURE & COMMUNITY 91 Game Development 108 Around the Regions 119 LEGAL, INTEGRITY & COMPLIANCE 135 STRATEGY & CLUB SERVICES 139 AWARDS, RESULTS & FAREWELLS 154 Obituaries 157 FINANCIAL REPORT 162 Concise Financial Report WINNING FEELING Coach Alastair Clarkson is a contented man after Hawthorn’s back-to-back premiership win. Ñ 4 AFL ANNUAL REPORT 2014 HIGHLIGHTS 5 2,828,139 The Seven Network audience for the 2014 Toyota AFL Grand Final which was the most watched program on television in 2014 in Australia’s five biggest capital cities. 3,733,409 The national metropolitan and regional audience for the 2014 Toyota AFL Grand Final. 99,460 THE ATTENDANCE HAPPY HAWKS Skipper and dual AT THE 2014 TOYOTA Norm Smith medallist Luke Hodge leads the Hawthorn celebrations after a superb Grand AFL GRAND FINAL Final display. Õ 6 AFL ANNUAL REPORT 2014 HIGHLIGHTS 7 PICTURE PERFECT The redeveloped Adelaide Oval 32,333 attracted more than a million The average attendance per game fans to the venue, for the 2014 Toyota AFL Premiership at an average of more than 46,000 Season, the fourth highest average a match. 6,402,010 attendance per game in the world Ô TOTAL ATTENDANCE for professional sport. 4,727,623 The total average aggregate FOR THE 2014 TOYOTA television audience for each week of the 2014 Toyota AFL AFL PREMIERSHIP SEASON Premiership Season. -

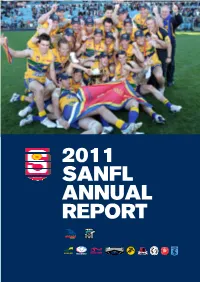

2011 Sanfl Annual Report

2011 SANFL ANNUAL REPORT L NF SA B LU C L L A B T O O F E D I A L E D C A T R O P M S AGPIE 1 INDEX Mission and Vision 4 Corporate Operations 62 Overview 64 2011: A Year In Review 6 SANFL Marketing 67 Events 68 SA Football Commission 10 Communications 70 Corporate Partnerships 71 Adelaide Oval 15 Commercial Operations 74 Football Operations 16 Overview 76 Overview 18 Stadium 77 State League 20 Crows & Power 78 Attendance 22 AAMI Stadium Attendance 79 Umpiring 28 Encore Group 80 Talent Development 30 Coaching 33 Financial Report 84 Community Engagement 34 Participation 36 SANFL Records 94 Inclusive Programs 39 Indigenous Football 43 Bereavements 105 Community Football 47 Committees 106 2011 Season 55 Premiers 56 2011 SANFL Fixture 107 Magarey Medal 58 Awards 60 Photo credits: Deb Curtis, Steven Laxton, Sarah Reed, Ben Hopkins, Stadium Management Authority, Emma-Lee Pedler, Luke Hemer, Stephen Laffer. 2 3 VISION & MISSION The League’s executive management team undertook a series of workshops in April 2011 to devise a detailed plan for the business over the next three years. The plan’s foundation was built on four central pillars: Our Game, Our Stadium, Our Future and Our People. The SA Football Commission approved the SANFL Strategic Plan: 2011 to 2014 in June 2011. The SANFL Vision: The SANFL Mission Statement: “To provide the ultimate experience in sport and “To protect, lead, manage entertainment at all levels.” and deliver the promotion and development of “At all levels” is a significant inclusion Australian football for the in the vision’s terms. -

2010 Yearbook

Drummoyne Power Junior Australian Football Club 2010 Yearbook Principal Sponsors Drummoyne Power – 2010 Yearbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Drummoyne Power Club Officials ........................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Committee 2010................................................................................................................................ 3 General Committee 2010................................................................................................................................... 3 Season 2010 Team Officials............................................................................................................................... 4 Drummoyne Power Junior Australian Football Club .......................................................................................... 5 Presidents Report .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Treasurer’s Report .................................................................................................................................................8 Vice President’s Report ........................................................................................................................................12 Auskick Coordinator’s Report ..............................................................................................................................14 Recruiting Manager’s