Maya Christina Gonzalez and Equity Minded Models at Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Call Me Tree: Llamame Arbol Ebook

CALL ME TREE: LLAMAME ARBOL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Maya Christina Gonzalez | 24 pages | 01 Nov 2014 | Children's Book Press (CA) | 9780892392940 | English, Spanish | United States Call Me Tree: Llamame Arbol PDF Book Post was not sent - check your email addresses! By beginning early and sharing age appropriate books that help kids see through gender assumptions, gender creative kids can relax and trust that they are perfectly natural and valuable. For Kids, Call Me Tree offers opportunities to: Become aware of gender assumptions and stereotypes and step away from "guessing" people's pronouns and gender based on stereotypes. Many of us assume a child with short hair, dressed in a t-shirt and pants is a cisgender boy. How did the character change over the course of the book? Jan 05, Alma rated it really liked it. Kirkus Reviews. Through the letter to readers kids understand that guessing about someone's gender based on how they look can leave a lot of people out. The American Library Association. And they pretty much mean the same thing every time someone looks at them. There are much better books available for this purpose. The Bay Area Reporter. Yet they all have roots and they all belong on the earth and in the world. Aug 19, Tasha rated it really liked it Shelves: picture-books. Retrieved 30 April Even so, it's more of a curriculum connection than something a child will pick up for an independent reading selection. I'm a tree person, and this book is wonderfully resonant. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. -

The Charlotte Zolotow Award Observations About Publishing in 1998

CCBC Choices Kathleen T. Horning Ginny Moore Kruse Megan Schliesman Cooperative Children's Book Center School of Education University of Wisconsin-Madison Copyright 01999, Friends of the CCBC, Inc. (ISBN 0-931641-98-5) CCBC Choices was produced by University Publications, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Cover design: Lois Ehlert For information about other CCBC publications, send a self- addressed, stamped envelope to: Cooperative Children's Book Cenrer, 4290 Helen C. White Hall, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 600 N. Park St., Madison, WI 53706-1403 USA. Inquiries may also be made via fax (6081262-4933) or e-mail ([email protected]).See the World Wide Web (http://www.soemadison.wisc.edu/ccbc/)for information about CCBC publications and the Cooperative Children's Book Center. Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Results of the CCBC Award Discussions The Charlotte Zolotow Award Observations about Publishing in 1998 The Choices The Natural World Seasons and Celebrations Folklore, Mythology and Traditional Literature Historical People, Places and Events Biography 1 Autobiography Contemporary People, Places and Events Issues in Today's World Understanding Oneself and Others The Arts Poetry Concept Books Board Books Picture Books for Younger Children Picture Books for Older Children Easy Fiction Fiction for Children Fiction for Teenagers New Editions of Old Favorites Appendices Appendix I: How to Obtain the Books in CCBC Choices and CCBC Publications Appendix 11: The Cooperative Children's Book Center (CCBC) Appendix 111: CCBC Book Discussion Guidelines Appendix IV: The Compilers of CCBC Choices 1998 Appendix V:The Friends of the CCBC, Inc. Index CCBC Choices 1778 5 Acknowledgments Thank you to Friends of the CCBC member Tana Elias for creating the index for this edition of CCBC Choices. -

Latino/A Children's and Young Adult Writers on the Art of Storytelling

INTRODUCTION THE HEART AND ART OF LATINO/A YOUNG PEOPLE’S FICTION Frederick Luis Aldama In the last decade, I found myself reading literature that is not meant nor marketed for my age group. This coincides with my compulsive need to share in all aspects of my daughter’s life. Corina is ten. In the past, I have relished in the marvelous art and word swirls of children’s picture books. Today, I am indulging more and more in the literary recreations of the sensory, cogni- tive, and emotional life of tweens and teens—especially those works by Lati- no authors. While there has been no prescriptive menu set—all themes and characters are up for grabs—the floors, baskets, and shelves in our Latino- Filipino (or, Mexipino) household spill over with books created by Latino authors and illustrators. Putting together this book is personal. It is a way for me to think more deeply about all the literature that I gorge on under Corina’s careful direction. It is also more. Indeed, it is about putting front and center for others (parents, teachers, students, and scholars) the creators and creations that make up this growing corpus of literature that draws from and radically expands our plan- etary republic of letters. It is about understanding the journeys of Latino au- thors and artists who commit their time, energy, and skill to giving shape to narratives that at once vitally reflect the myriad of experiences of young Lati- nos in the United States and that invite others to share in these experiences. -

Call Me Tree: Llamame Arbol Free

FREE CALL ME TREE: LLAMAME ARBOL PDF Maya Christina Gonzalez | 24 pages | 01 Nov 2014 | Children's Book Press (CA) | 9780892392940 | English, Spanish | United States Maya Christina Gonzalez - Wikipedia Maya Christina Gonzalez born is an award-winning queer Call Me Tree: Llamame Arbol artist, illustrator, educator and publisher. Gonzalez is a co-founder of the publishing house, Reflection Press. This early gift inspired her to start drawing and introduced her to how art can help Call Me Tree: Llamame Arbol. At age thirteen, Gonzalez and her family moved to rural Oregon where she experienced racism and homophobia. This is when she began painting. Gonzalez was prompted to move from Oregon to San Francisco after she was shot at while living in a lesbian wilderness community. After leaving school with only a few art classes taken, Gonzalez explored creating her Call Me Tree: Llamame Arbol art. At this time, Gonzales was interested in exploring the nature of "reality, consciousness and how these relate to creativity" and was very influenced by Jane Roberts ' channeling of another consciousness that Roberts referred to as Seth. Harriet asked if she would be interested in illustrating children's books which is ultimately what lead Gonzal to her passion for illustrating. InGonzalez suffered from a toxic dose of chemicals in a print-making accident. I'm in line with my beliefs and completely out of line with the beliefs of the dominant culture. Gonzalez's art depicts non-stereotypical images of people, including overweight individuals and empowered women. Gonzalez considers it very important as a child to see oneself depicted in books. -

LGBTQ+ Literature Read-In Week Recommended Booklist 2020

3rd Annual LGBTQ+ Literature Read-In Week Recommended Booklist 2020 This is a small list of books that we feel will make volunteers successful when reading aloud to a group of students to celebrate gender diversity. Our list does not intend to represent everyone, and we welcome any feedback or additional titles you may care to share. We have worked with multiple community partners to compile our list. Featured Recommendations 1. And Tango Makes Three Authors: Justin Richardson & Peter Parnell Grade: PreK – K YouTube Link: https://youtu.be/qOkDAZelvk8 Description: The heartwarming true story of two penguins who create a nontraditional family is now available in a sturdy board book edition At the penguin house at the Central Park Zoo two penguins named Roy and Silo were a little bit different from the others But their desire for a family was the same And with the help of a kindly zookeeper Roy and Silo got the chance to welcome a baby penguin of their very own In time for the tenth anniversary of And Tango Makes Three this Classic Board Book edition is the perfect size for small hands. 2. Antonio’s Card | La tarjeta de Antonio Author: Rigoberto González nd rd Grade: 2 – 3 Grade Description: Antonio loves words, because words have the power to express feelings like love, pride, or hurt. Mother's Day is coming soon, and Antonio searches for the words to express his love for his mother and her partner, Leslie. But he's not sure what to do when his classmates make fun of Leslie, an artist, who towers over everyone and wears paint-splattered overalls. -

CHOICES2000.Pdf (2.168Mb)

Choices CCBC Kathleen T. Horning Ginny Moore Kruse Megan Schliesman Cooperative Children's Book Center School of Education University of Wisconsin-Madison Copyrighr 02000, Friends of the CCAC, Inc. (ISBN 0-931641-10-1) There is no publication titled C'CBC Choices 1999. C(,'BCChoices 2000 contains books during 1999. CCBC Choices 1998 contained books published during 1998. CCBC Choices was produced by University Publications, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Cover design: Lois Ehlert For infornlarion about other CCBC publications, send a self- addressed, stamped envelope ro: Cooperative Children's Book Center, 4290 Helen C. White Hall, School of Educarion, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 600 N. Park St., Madison, WI 53706-140.3 USA. Inquiries may also be made via f;ix (608/2624933) or e-mail ([email protected]). See the World Wide Wet) (http://zuww.edu~~ntiorz.wzsc.~du/ccrl,c~for information about CCBC publicatious and the Cooperative Children's Book Center. Contents Acknowledgments .............................................5 Introduction .................................................6 Results of the CCBC Award Discussions ............................7 The Charlotte Zolotow Award ....................................8 Observations about Publishing in 1999 ............................10 The Choices The Natural World .......................................22 Seasons and Celebrations ...................................24 Folklore. Mythology. and Traditional Literature ..................28 Historical People. Places. and Events -

Embracing Gender Identity Booklist

Embracing Gender Identities is an ALSC booklist created to help support conversations about gender identity and EMBRACING expression. This list, which is divided into books for 0-5 year-olds, elementary school students and middle schoolers, includes recommended informational picture books, GENDER as well as works of fiction and non-fiction that challenge gender norms and explore the wide spectrum of gender identity. It IDENTITIES includes additional resources for parents. Birth–Preschool (Ages 0–5) Clive and His Babies Julián Is a Mermaid Red: A Crayon’s Story by Jessica Spanyol by Jessica Love by Michael Hall Child’s Play International, 2016, ISBN: 9781846438820 Candlewick Press, 2018, ISBN: 9780763690458 Greenwillow Books, 2015, ISBN: 9780062252074 First in a series of board books about a boy Julián LOVES mermaids! A summer afternoon This heartwarming picture book follows the whose love for imaginative play includes of dress-up fantasy is only improved by a story of a blue crayon who is mistakenly dolls, hats, glitter, art, and a diverse group of surprise from Abuela. labeled as “red,” until he discovers his true friends. identity as a blue crayon and celebrates the strength he finds in being his true self. Neither I Am Jazz! by Airlie Anderson by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings, illustrated by Little, Brown, 2018, ISBN: 9780316547697 Teddy’s Favorite Toy Shelagh McNicholas The Land of This and That is too restrictive for by Christian Trimmer, illustrated by Madeline Valentine Dial Books, 2014, ISBN: 9780803741072 the individualistic Neither. But a more colorful Atheneum Books, 2018, ISBN: 9781481480796 This is the real-life story of Jazz Jennings, a and open-minded home is waiting to embrace Teddy’s mom accidentally throws out his transgender child who knew from a very early Neither. -

Pride Month Resource List

LGBTQIA+ Pride Month Resources for Teachers, Staff and Families Times may be tough, but there’s no stopping the celebration of the spectrum of human experience in June. We are here to commemorate the generations lost to years of persecution and to epidemics like the AIDs crisis, as well as show love to today’s LGBTQIA+ people of all ages, genders, sexualities, and orientations. This year (2021), the Dobbs Ferry Public Schools have teamed up to mark an intersectional Pride Month by creating a resource list in partnership with the Dobbs Ferry Public Library. Springhurst librarian Lauren Rodriguez, Middle/High School media specialist Ellen Elsen, and K-8 Literacy Coordinator Michelle Yang-Kaczmarek have teamed up with Dobbs Ferry Public Library children’s librarian Gina Elbert and teen librarian Allee Manning to create this resource list to help you dive deeper into queer literature for kindergarten through 12th grade. This is a sampling of available resources and not an exhaustive list. If you would like help finding more, please contact your librarian(s). Online Resources “9 LGBTQ+ People Explain How They Love, Hate, and Understand the Word ‘Queer’.” https://www.them.us/story/what-does-queer-mean "Queer" is used by more people — and more variously defined — than ever before. In their own words, nine LGBTQ+ people explain what this divisive, liberating term means to them. “Building Diverse Collections of LGBTQ-Inclusive Children’s Literature to Expand Windows and Mirrors for Youth” by Stephen Adam Crawley https://ncte.org/blog/2019/03/lgbtq-inclusive-childrens-literature/ This blog post can help guide teachers in making selections for their classroom libraries that represent the totality of the population of children that they serve. -

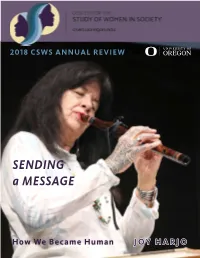

SENDING a MESSAGE

2018 CSWS ANNUAL REVIEW SENDING a MESSAGE How We Became Human JOY HARJO 2018-19 CSWS Events FALL 2018 WINTER 2019 September 24 January 30 – February 1 Race, Ethnicities, and Inequalities Colloquium Common Reading Program: Author Thi Bui. “The Invisible #MeToos: The fight to end Public Talk: “The Best We Could Do.” Jan. sexual violence against America’s most 31. Time & location: TBD. vulnerable workers.” Investigative reporter Bernice Yeung. 2 pm Knight Law Center. Bernice Yeung February 11–12 Thi Bui October 3 ALLYSHIP TRAININGS: Attorney Janée Woods. Many Nations Longhouse. 1630 PANEL: “Trans* Law: Columbia St. 8:30 am – 1 pm on 2/11/18. 9 Opportunities and am – 3 pm on 2/12/18 Must pre-register. Futures.” Attorney Asaf Orr & Prof. Paisley Janée Woods Currah. Beatrice Dohrn, moderator. 12 pm Room February 26 –28 Paisley Currah Asaf Orr, Esq. 175, Knight Law Center. “Why Aren’t There More Black People in Oregon?: A Hidden History.” Author October 17 Walidah Imarisha. Public Lecture: Feb. 27. “Written/Unwritten: On the Promise and Time & location TBD. Limits of Diversity and Inclusion.” Patricia Walidah Imarisha Matthew, Montclair State University. 3:30 March 7 pm EMU 230, Swindells Room. Race, Ethnicities, and Inequalities Colloquium: “Facing the Dragon.” Christen October 25 Smith, University Texas, Austin. Knight Law “Surviving State Patricia Matthew Center. Terror: Women’s Testimonies of Repression and Resistance Christen Smith in Argentina.” Barbara Sutton, University at Albany, SUNY, 12:30 pm Gerlinger Lounge. SPRING 2019 Barbara Sutton April 25 November 30 2019 Acker-Morgen Lecture: “Masculinity Raka Ray “Gender and Climate Change.” Joane Nagel, and Capitalism: A Brief History of the Rise University of Kansas. -

A Queer History of the United States for Young People Discussion Guide

A Queer History of the United States for Young People Discussion Guide Note to Educators: In the prologue to A Queer History of the United States for Young People, Michael Bronski notes that the “official” history of our nation often ignores certain groups of people, or erases parts of their identity, when they are mentioned in textbooks. He states, “For LGBTQ people—and especially youth and people just coming out—it’s not as easy to find out our true history. It’s not taught in schools” (p. xviii). It is extremely important for all students to understand the accomplishments, achievements, and contributions that lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and other queer (LGBTQ) individuals have made to United States history. LGBTQ students need role models that reinforce it is okay to be queer and that they are not alone. For the non-queer student, it is equally essential to learn that LGBTQ individuals were fighting for many social justice and issues throughout US history. Bronski acknowledges, “If we are erased from the history books, then how can we ever know who we are? This absence, this erasure, denies us the right and the ability to use our history as a guide, to feel pride in the heroism and accomplishments of the LGBTQ people who came before us. And it denies us the ability to use this history as a guide to the future so we can follow in their footsteps” (p. xix). A Queer History of the United States for Young People, adapted by Richie Chevat, provides a glimpse into some of the many contributions that queer people have made throughout our history. -

June 4, 2021 Hello Wauwatosa Community, Please Find This Week's

June 4, 2021 Hello Wauwatosa Community, Please find this week’s updates below. LGBTQ+ Pride Month Pride Month started as a tribute to those involved in the Stonewall Riots in New York in 1969 and today is celebrated globally. One goal of Pride Month is to achieve equal justice and equal opportunity for people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ). To learn more about the history of Pride Month, please click here. Please also click here to access the MKE LGBT Community Center Resource Center, which is a one-stop-shop for valuable information including counseling programs, hotlines, clinics, support groups and more! We also encourage elementary students and their families to explore the following books, which are available at your elementary school library! • Celebrating Transgender & Non Binary Identities o When Aidan Became a Big Brother by Kyle Lukoff o Jack (Not Jackie) by Erica Silverman o It Feels Good to Be Yourself: A Book About Gender Identity by Theresa Thorn o Call Me Tree: Llȧmame Ȧrbol by Maya Christina Gonzalez • Celebrating Gender Expression o Juliȧn is a Mermaid by Jessica Love o The Boy and the Bindi by Vivek Shraya • Celebrating All Families o One Family by George Shannon o And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson o My Footprints by Bao Phi o The Family Book by Todd Parr • Celebrating Pride Month: History & History Makers o Pride: The Story of Harvey Milk and the Rainbow Flag by Rob Sanders o Queer There and Everywhere: 23 People Who Changed the World by Sarah Prager [available at Wauwatosa High School libraries] The Wauwatosa School District is committed to further deepen our work to provide safe, welcoming, inclusive, affirming environments for LGBTQ+ staff, students, family members, and community members. -

New Picture Book Makes Trans and Nonbinary Inclusion As Fundamental As the Abcs

New Picture Book Makes Trans and Nonbinary Inclusion as Fundamental as the ABCs With the current presidential administration rolling back protections for transgender and nonbinary students and adults, it’s more important than ever to instill in children a respect for and celebration of gender diversity. A new picture book, They, She, He easy as ABC dismantles rigid gender stereotypes and assumptions and encourages very young readers to practice using inclusive pronouns right alongside learning the alphabet. Written and illustrated by Pura Belpre Honor Award winner Maya Christina Gonzalez and joined by her partner Matthew, They, She, He easy as ABC is a playful rhyming celebration of children’s naturally diverse and exuberantly fluid expression. https://vimeo.com/330911530?loop=0 “Pronouns are one of the first ways that kids are taught to gender themselves and others. By linking gender inclusive pronouns with something as fundamental as learning the ABCs, we can model that gender inclusion is as essential as language acquisition.” – Maya Gonzalez, co-author & illustrator They, She, He easy as ABC continues the work started by Maya & Matthew in their previous debut book together, They She He Me: Free to Be! released in 2017 which School Library Journal gave a starred review saying“the authors have succeeded in creating a gorgeous and much-needed picture book about pronouns and gender fluidity. A beautiful and gentle exploration of identity and kindness.” Both books are part of theGender Wheel curriculum and published through Reflection Press, an independent publishing house founded by Maya and Matthew in 2009 with the intention to create the books about their communities they feel are missing from the traditional publishing scene.