Hydrographic Data As Indicators of Physical Development on the Trinidad West Coast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrimp Fishing in Mexico

235 Shrimp fishing in Mexico Based on the work of D. Aguilar and J. Grande-Vidal AN OVERVIEW Mexico has coastlines of 8 475 km along the Pacific and 3 294 km along the Atlantic Oceans. Shrimp fishing in Mexico takes place in the Pacific, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, both by artisanal and industrial fleets. A large number of small fishing vessels use many types of gear to catch shrimp. The larger offshore shrimp vessels, numbering about 2 212, trawl using either two nets (Pacific side) or four nets (Atlantic). In 2003, shrimp production in Mexico of 123 905 tonnes came from three sources: 21.26 percent from artisanal fisheries, 28.41 percent from industrial fisheries and 50.33 percent from aquaculture activities. Shrimp is the most important fishery commodity produced in Mexico in terms of value, exports and employment. Catches of Mexican Pacific shrimp appear to have reached their maximum. There is general recognition that overcapacity is a problem in the various shrimp fleets. DEVELOPMENT AND STRUCTURE Although trawling for shrimp started in the late 1920s, shrimp has been captured in inshore areas since pre-Columbian times. Magallón-Barajas (1987) describes the lagoon shrimp fishery, developed in the pre-Hispanic era by natives of the southeastern Gulf of California, which used barriers built with mangrove sticks across the channels and mouths of estuaries and lagoons. The National Fisheries Institute (INP, 2000) and Magallón-Barajas (1987) reviewed the history of shrimp fishing on the Pacific coast of Mexico. It began in 1921 at Guaymas with two United States boats. -

Sea Level Rise and Land Use Planning in Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Pará

Water, Water Everywhere: Sea Level Rise and Land Use Planning in Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Pará Thomas E. Bassett and Gregory R. Scruggs © 2013 Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper The findings and conclusions of this Working Paper reflect the views of the author(s) and have not been subject to a detailed review by the staff of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Contact the Lincoln Institute with questions or requests for permission to reprint this paper. [email protected] Lincoln Institute Product Code: WP13TB1 Abstract The Caribbean and northern coastal Brazil face severe impacts from climate change, particularly from sea-level rise. This paper analyses current land use and development policies in three Caribbean locations and one at the mouth of the Amazon River to determine if these policies are sufficient to protect economic, natural, and population resources based on current projections of urbanization and sea-level rise. Where policies are not deemed sufficient, the authors will address the question of how land use and infrastructure policies could be adjusted to most cost- effectively mitigate the negative impacts of climate change on the economies and urban populations. Keywords: sea-level rise, land use planning, coastal development, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Pará, Brazil About the Authors Thomas E. Bassett is a senior program associate at the American Planning Association. He works on the Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas grant from the U.S. Department of State as well as the domestic Community Assistance Program. Thomas E. Bassett 1030 15th Street NW Suite 750W Washington, DC 20005 Phone: 202-349-1028 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Gregory R. -

Observations of Pelagic Seabirds Wintering at Sea in the Southeastern Caribbean William L

Pp. 104-110 in Studies in Trinidad and Tobago Ornithology Honouring Richard ffrench (F. E. Hayes and S. A. Temple, Eds.). Dept. Life Sci., Univ. West Indies, St. Augustine, Occ. Pap. 11, 2000 OBSERVATIONS OF PELAGIC SEABIRDS WINTERING AT SEA IN THE SOUTHEASTERN CARIBBEAN WILLIAM L. MURPHY, 8265 Glengarry Court, Indianapolis, IN 46236, USA ABSTRACT.-I report observations, including several the educational cruise ship Yorktown Clipper between significant distributional records, of 16 species of Curaçao and the Orinoco River, traversing seabirds wintering at sea in the southeastern Caribbean approximately 2,000 km per trip (Table 1). Because during cruises from Bonaire to the Orinoco River (5-13 the focus was on visiting islands as well as on cruising, January 1996, 3-12 March 1997, and 23 December many of the longer passages were traversed at night. 1997 - 1 January 1998). A few scattered shearwaters While at sea during the day, fellow birders and I (Calonectris diomedea and Puffinus lherminieri) were maintained a sea watch, recording sightings of bird seen. Storm-Petrels (Oceanites oceanicus and species and their numbers. Oceanodroma leucorhoa), particularly the latter species, were often seen toward the east. Most The observers were all experienced birders with tropicbirds (Phaethon aethereus) and gulls (Larus binoculars, some of which were image-stabilised. The atricilla) were near Tobago. Boobies were common; number of observers at any given time ranged from Sula leucogaster outnumbered S. sula by about 4:1 and one to 15, averaging about five. Observations were S. dactylatra was scarce. Frigatebirds (Fregata made from various points on three decks ranging from magnificens) were strictly coastal. -

C-Map by Jeppesen Mm3d Coverage

C-MAP BY JEPPESEN MM3D COVERAGE NORTH AMERICA WVJNAM021MAP – Canada North & East MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM021MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide WVJNAM022MAP – USA East Coast and Bahamas MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM022MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide 9 WVJNAM023MAP – Gulf of Mexico, Great Lakes & Rivers MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM023MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide WVJNAM024MAP – West Coast & Hawaii MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM024MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide 10 WVNJNAM025MAP – Canada West MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM025MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide WVJNAM026MAP – Great Lakes & Canadian Maritimes MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM026MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide 11 WVJNAM027MAP – Central America & Caribbean MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM027MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide WVJNAM028MAP - Alaska MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM028MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 – Wide 12 MWVJNAM033MAP – Atl. Coast, Gulf of MX & Caribbean MM3D File Name: (2files) SDVJNAM033NMAP0x.dbv and SDVJNAM033SMAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $600.00 – MegaWide MWVJNAM035MAP – Pacific Coast and Central America MM3D File Name: SDVJNAM035NMAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $600.00 –MegaWide 13 SOUTH AMERICA WVJSAM500MAP – Costa Rica to Chile to Falklands MM3D File Name: SDVJSAM500MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 –Wide WVJSAM501MAP – Gulf of Paria to Cape Horn MM3D File Name: SDVJSAM501MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $300.00 –Wide 14 MWVJSAM504MAP – South America & US Gulf Coast MM3D File Name: SDVJSAM504MAP0x.dbv Retail Price: $600.00 –MegaWide MAX LAKES WVJNAM017MAP – MAX Lakes North MM3D File Name: -

Experimental Investigations Into Manufacturing Processes

K. Hall and G. Shrivastava.: Marine Current Power Generation in Trinidad: A Case Study 15 ISSN 0511-5728 The West Indian Journal of Engineering Vol.39, No.2, January 2017, pp.15-24 Marine Current Power Generation in Trinidad: A Case Study Kashawn Hall a,Ψ, and Gyan Shrivastavab Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies; aE-mail: [email protected] b E-mail: [email protected] Ψ Corresponding Author (Received 19 April 2016; Revised 22 August 2016; Accepted 6 December 2016) Abstract: Development of alternative energy sources has attracted worldwide interest given the adverse effects of fossil fuels on the global climate as well as its unsustainability. It is in this context that this report examines the feasibility of marine power generation at the 14 km wide Serpent’s Mouth in Trinidad. It is part of the narrow Columbus Channel which lies between Trinidad and Venezuela. At this location, depth varies between 30 - 48 m and a marine current of approximately 1.5 m/s suggests the possibility of generating power through submerged turbines.The conditions are similar to those at Strangford Lough in the Irish Sea, where the world’s first marine current turbine was installed in 2008 for generating 2 MW of power. After taking into account the technical, environmental, and economic factors, this paper concludes it is feasible to use The Serpent’s Mouth location for Power Generation. Keywords: Columbus Channel, Marine Current Turbines (MCTs), Power Generation, Marine Renewable Energy (MRE) 1. -

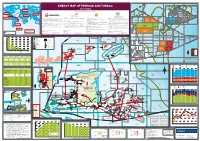

View the Energy Map of Trinidad and Tobago, 2017 Edition

Trinidad and Tobago LNG export destinations 2015 (million m3 of LNG) Trinidad and Tobago deepwater area for development 60°W 59°W 58°W Trinidad and Tobago territorial waters ENERGY MAP OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 1000 2000 m m 2017 edition GRENADA BARBADOS Trinidad and Tobago 2000m LNG to Europe A tlantic Ocean 2.91 million m3 LNG A TLANTIC Caribbean 2000m 20 Produced by Petroleum Economist, in association with 00 O CEAN EUROPE Sea m Trinidad and Tobago 2000m LNG to North America NORTH AMERICA Trinidad and Tobago 5.69 million m3 LNG LNG to Asia 3 GO TTDAA 30 TTDAA 31 TTDAA 32 BA 1.02 million m LNG TO Trinidad and Tobago OPEN OPEN OPEN 12°N LNG to MENA 3 1.90 million m LNG ASIA Trinidad and Tobago CARIBBEAN TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 2000m LNG to Caribbean Atlantic LNG Company profile Company Profile Company profile Company Profile 3 Established by the Government of Trinidad and Tobago in August 1975, The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) is an BHP Billiton is a leading global resources company with a Petroleum Business that includes exploration, development, production and marketing Shell has been in Trinidad and Tobago for over 100 years and has played a major role in the development of its oil and gas industry. Petroleum Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (Petrotrin) is an integrated Oil and Gas Company engaged in the full range of petroleum 3.84 million m LNG internationally investment-graded company that is strategically positioned in the midstream of the natural gas value chain. -

![Weber Et Al., 2001A; Pérez Et Al., 2001]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9412/weber-et-al-2001a-p%C3%A9rez-et-al-2001-2439412.webp)

Weber Et Al., 2001A; Pérez Et Al., 2001]

PUBLICATIONS Tectonics RESEARCH ARTICLE Tectonic inversion in the Caribbean-South American 10.1002/2014TC003665 plate boundary: GPS geodesy, seismology, Key Points: and tectonics of the Mw 6.7 22 April • The 22 April 1997 Mw 6.7 Tobago earthquake inverted a low-angle 1997 Tobago earthquake thrust fault • Seismology, GPS, and modeling John C. Weber1, Halldor Geirsson2, Joan L. Latchman3, Kenton Shaw1, Peter La Femina2, resolve coseismic slip, fault geometry, 4 3 1 4,5 and moment Shimon Wdowinski , Machel Higgins , Christopher Churches , and Edmundo Norabuena • Coseismic slip subsided Tobago and 1 2 moved it NNE Department of Geology, Grand Valley State College, Allendale, Michigan, USA, Department of Geosciences, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA, 3Seismic Research Centre, University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, 4RSMAS-Geodesy Lab, University of Miami, Miami, Florida, USA, 5Now at Instituto Geofisica del Peru, Lima, Peru Correspondence to: J. C. Weber, [email protected] Abstract On 22 April 1997 the largest earthquake recorded in the Trinidad-Tobago segment of the Caribbean-South American plate boundary zone (Mw 6.7) ruptured a shallow (~9 km), ENE striking (~250° Citation: azimuth), shallowly dipping (~28°) dextral-normal fault ~10 km south of Tobago. In this study, we describe Weber, J. C., H. Geirsson, J. L. Latchman, this earthquake and related foreshock and aftershock seismicity, derive coseismic offsets using GPS data, K. Shaw, P. La Femina, S. Wdowinski, M. Higgins, C. Churches, and E. Norabuena and model the fault plane and magnitude of slip for this earthquake. Coseismic slip estimated at our episodic (2015), Tectonic inversion in the GPS sites indicates movement of Tobago 135 ± 6 to 68 ± 6 mm NNE and subsidence of 7 ± 9 to 0 mm. -

Latin America & the Caribbean

LATIN AMERICA & THE CARIBBEAN Monthly Humanitarian Snapshot As of 1 November 2018 1. CENTRAL AMERICA - FLOODING 2. MEXICO - SEVERE STORMS AND FLOODING 3. COLOMBIA - FLOODING 6 Atlantic Ocean 2 MEXICO HAITI PEOPLE THROUGHOUT CENTRAL PEOPLE EVACUATED BY THE PEOPLE AFFECTED THROUGHOUT 4 AMERICAN COUNTRIES GOVERNMENT OF MEXICO DUE TO LA GUAJIRA DUE TO HEAVY 201K AFFECTED BY SEVERE FLOODS 13K HURRICANE WILLA 64K RAINFALL AND FLOODING HONDURAS TRINIDAD GUATEMALA AND TOBAGO NICARAGUA Caribbean Sea EL SALVADOR MEXICO 1001+ 3 5 BELIZE VENEZUELA VENEZUELA MEXICO HONDURAS PEOPLE AFFECTED 601 - 1000 1 GUYANA COLOMBIA BY FLOODS 301 - 600 COSTA RICA COLOMBIA 7 1 - 300 BRAZIL Guatemala SINALOA ECUADOR Tegucigalpa ECUADOR San Salvador Océano Pacífico ALBANIA NAYARIT BRAZIL CaribbeanYUCATÁN Sea GUATEMALA URIBIA Pacific Ocean NICARAGUA Mexico PERU EL SALVADOR City VERACRUZ Mar Caribe QUINTANA MICHOACAN ROO Managua CAMPECHE FONSECA Departments affected OAXACA BELICE by long term droughts States affected by Hurricane Willa RIOHACHA ISLAS DE LA BAHÍA States affected by Tropical Storm Vicente Departments affected by floods San Jose TEGUCIGALPA HONDURAS States affected by floods VENEZUELA Departments affected COSTA RICA both by floods and droughts PANAMA EL SALVADOR Source: Ministry of the Interior Source: DepartmentalNICARAGUA Council for Disaster Risk Management Intense flooding throughout Central America 1 has caused losses to livelihoods and lives $117M 5.3K 38 30K 10K 11 2K 80% 19 Flooding, a tropical cyclone and a tropical IN ECONOMIC LOSSES PEOPLE IN 47 -

The Shrimp and Groundfish Fisheries of Trinidad and Tobago

55 NATIONAL REPORT OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO The shrimp and groundfish fisheries of Trinidad and Tobago by Fisheries Division, Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Marine Resources Trinidad and Tobago7 1. DESCRIPTION OF THE SHRIMP TRAWL FISHERY The demersal trawl fishery has been described as the country’s most valuable fishery in terms of landings, dollar value and foreign exchange earnings (Fabres, 1989; Amos, 1990). The principal exploited species are the Penaeids: Penaeus brasiliensis (hoppers), P. notialis (pink shrimp), P. schmitti (white/cork shrimp), P. subtilis (brown shrimp) and Xiphopenaeus kroyeri (honey/jinga shrimp). The latter species is also targeted by bait trawlers. A significant quantity of finfish, crabs and squid are landed as by-catch. There are four trawler fleets: two inshore, artisanal fleets; an offshore, semi-industrial fleet; and an offshore industrial fleet. Major trawling activities are centered around the Gulf of Paria in the west, the Columbus Channel in the south and seasonally in areas off the north coast. Several species of groundfish exploited incidentally in the demersal trawl fishery are also targeted by an inshore gillnet fishery. The most commercially important and abundant species are Micropogonias furnieri and Cynoscion jamaicensis. 1.1 Fleet Description and Fishing Zones A census of fishing vessels conducted in November 1991 identified some two hundred and nine (209) active, locally registered trawlers. These vessels are categorised into four (4) types (Types I - IV) according to their lengths, engine horsepower and degree of mechanisation (Maharaj et al., 1993). Nine (9) trawlers currently comprise the semi-industrial fleet (Type III) and twenty one (21) the industrial (Type IV) fleet. -

Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem Regional Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

Sustainable Management of the Shared Living Marine Resources of the Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem & Adjacent Regions CLME REGIONAL TRANSBOUNDARY DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS Peter Whalley July 2011 Sustainable Management of the Shared Living Marine Resources of the Caribbean Sea Large Marine Ecosystem (CLME) and Adjacent Regions Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem Regional Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis Prepared by the UNDP/GEF CLME Project July 2011 Acknowledgements The UNDP/GEF CLME Project acknowledges the considerable effort in preparing this Regional Transboundary Analysis and the contributions from both regional and international experts. In particular, the CLME Project wishes to acknowledge the preparation of the three fisheries ecosystem and governance reports by Sherry Heileman, Terrence Philips and Robin Mahon, together with their support to Peter Whalley in the synthesis of these reports in to this Regional TDA. In addition the CLME Project wishes to thank input and advice from: The National Focal Points: James C. Gumbs , Cheryl Appleton , Mr. Michael T Braynen , Lorna Inniss , Beverly Wade, Lucia Maria Maierá., Xiomara L. Sanclemente M., Jenny Asch Corrales , Derrick Theophille , Ydalia Acevedo , Francis Calliste , Mario Abel Díaz Anzueto , Robin Austin , Lucienna Exil , Rafael Amaro García , Sheries Simpson , Salomón Díaz Mondragón, Albert Martis , Carlos Ramiro Mejía Urbina , Ingrid Sainz , Ralph Wilkins , Rufus George , Raymond Joel Ryan , Ellis Wendly , Elizabeth Mohammed , Wesley Clerveaux , Marco Aurelio Fernández , James Azueta, Zoraida Fajardo Rodríguez , Andrea Ramírez , Joseph Astrel , Lara Ferreira, José Ramón Delgado. The Technical Task Team James Berkson, Fabian Blachard, Angelique Braithwaite, Georgina Bustamente, Lucia Fanning, Sarah George, Terrence Philips, Juan Carlos Seijo, Bevely Wade, Nestor Windevoxhel The Stakeholder Advisory Group John Agard, Mitchell Lay, Adolfo Lopez Belando, Patrick McConney, Sarah McIntosh, Manuel Perez Moreno, Michele Picou-Gill, Xiomara Sanclemente, Deirde Shurland The Project Co-ordination Unit G. -

Sea Turtles of the Caribbean

SWOT report Volume XV The State of the World’s Sea Turtles SPECIAL FEATURE Sea Turtles of the Caribbean INSIDE: INDIAN OCEAN LOGGERHEADS DRONES FOR CONSERVATION JAGUARS AND MORE … A bubble forms as a green turtle exhales at the surface. © Ben J. Hicks/benjhicks.com. FRONT COVER: A leatherback turtle finishes her nesting process as day breaks in Grande Riviere, Trinidad. © Ben J. Hicks/benjhicks.com 2 | SWOT REPORT SEATURTLESTATUS.ORG | 1 2 | SWOT REPORT Editor’s Note No Sea Turtle Is an Island ise men and women throughout history have shown us that, “there is Wpower in unity and there is power in numbers” (Martin Luther King Jr., 1963). That is certainly the case with the State of the World’s Sea Turtles (SWOT) program, the world’s largest volunteer network of sea turtle researchers, conservationists, and enthusiasts. This volume of SWOT Report unifies an enormous cast: from the hundreds of researchers in more than 20 countries, whose collective efforts can be seen in the first-ever global-scale map of loggerhead sea turtle telemetry (pp. 32–33), to the beach workers from the Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST) and beyond, whose labors are seen in this issue’s maps of sea turtle biogeography (pp. 24–27). As you peruse these cartographic works of art, reflect for a moment on the time, effort, and passion that went into each of those tiny, tinted polygons of telemetry data or the myriad multicolored circles of nest abundance. Together they represent the labors of a multitude of beach workers, synergistically amassed to bring big-picture visualizations of sea turtle natural history to life as never before. -

Maritime Investment Guide for the Gulf of Paria, Trinidad and Tobago

LOCATE NOW - SAFE HARBOUR FOR YOUR INVESTMENT MARITIME INVESTMENT GUIDE FOR THE GULF OF PARIA, TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Transshipment and Lay-ups (Cold-stacking & Warm Stacking) #1 CARIBBEAN LOCATION FOR MARITIME OPERATIONS Trinidad’s 2,940 km2 of naturally sheltered harbor is considered the best on the Atlantic Coast and elevates the destination to the number one location in the Caribbean region for maritime businesses and the ideal site for Transshipment operations and Lay-ups – Cold and Warm Stacking. Maritime Investment Guide 1 EUROPE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA TRINIDAD AFRICA AND PANAMA TOBAGO VENEZUELA COLOMBIA GUYANA PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Trinidad and Tobago’s navigational location is Latitude The Gulf of Paria, designated as the site for 10° 20’ 00” and Longitude 62° 00’ 00” which places it transshipment and layup operations, is a 7,989 km2 well at the southernmost end of the hurricane belt, with sheltered inland sea of which Trinidad and Tobago a historically low risk of direct hurricane impact. The has legal jurisdiction over 2,940km2. It encompasses twin island republic lies just 11km off the coast of the western coast of Trinidad with a total of 156km South America and is the southernmost island in the of coastline. Caribbean Basin. There are two international container ports, a The country is approximately 19km away from port serving one of the largest LNG facilities in the international shipping lanes used by vessels going to western hemisphere and another serving oil and fuel and from the USA and European Union and 2,011km shipment operations. east of the Panama Canal.