The Last Cowboy in Sussex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Word Version

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Adur in West Sussex Report to The Electoral Commission July 2002 THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND © Crown Copyright 2002 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. Report No: 306 2 THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? 5 SUMMARY 7 1 INTRODUCTION 11 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 13 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 17 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 19 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 21 6 WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? 37 A large map illustrating the proposed ward boundaries for Adur is inserted at the back of this report. THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND 3 4 THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. The functions of the Local Government Commission for England were transferred to The Electoral Commission and its Boundary Committee on 1 April 2002 by the Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (SI 2001 No. 3692). The Order also transferred to The Electoral Commission the functions of the Secretary of State in relation to taking decisions on recommendations for changes to local authority electoral arrangements and implementing them. -

Tuesday, February 4, 2014

22016 2014.FEMMY.Covers_Layout 1 1/30/14 11:33 AM Page 1 Supporting Education Today for A Better Industry Tomorrow The Underfashion Club, Inc 326 Field Road Clinton Corners, NY 12514 P: 845.758.6405 Presented by F: 845.758.2546 [email protected] www.underfashionclub.org Tuesday, February 4, 2014 22016 2014.FEMMY.Covers_Layout 1 1/30/14 11:33 AM Page 2 22016 2014.FEMMY.Pages.1-32_47443-Femmy PG 1-24 1/30/14 11:26 AM Page 1 WE ARE PROUD TO BE RECOGNIZED BY THE THE UNDERFASHION CLUB, INC. AND APPLAUD ALL OF THIS EVENING’S HONOREES 22016 2014.FEMMY.Pages.1-32_47443-Femmy PG 1-24 1/30/14 11:26 AM Page 2 22016 2014.FEMMY.Pages.1-32_47443-Femmy PG 1-24 1/30/14 11:26 AM Page 3 22016 2014.FEMMY.Pages.1-32_47443-Femmy PG 1-24 1/30/14 11:26 AM Page 4 FASHION FORMS SALUTES FEMMY HONOREES: Hudson Bay Company Lord & Taylor Delta Galil Industries, Ltd. Iluna USA LLC INNOVATION AWARD RECIPIENT Jockey International, Inc. LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD RECIPIENT Seth Morris & A special congratulations from Ann & your friends at Fashion Forms to PRESIDENT’S AWARD RECIPIENT ROSLYN HARTE THE MOST INNOVATIVE BRAND FOR BRA SOLUTIONS www.FASHIONFORMS.com 22016 2014.FEMMY.Pages.1-32_47443-Femmy PG 1-24 1/30/14 11:26 AM Page 5 The Underfashion Club, Inc. Karen Bromley and Barbara Lipton Femmy Gala Chairpersons welcome you to the FEMMY GALA 2014 HONORING HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY l LORD & TAYLOR Accepted by MARYANNE MORIN Group Senior Vice President _______________________________ DELTA GALIL INDUSTRIES, LTD. -

East Worthing Flood Alleviation Scheme Teville Stream – Hydraulic Modelling Report

East Worthing Flood Alleviation Scheme Teville Stream – Hydraulic Modelling Report November 2011 Environment Agency EW FAS Teville Stream Model Build Report November 2011 Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 2 1.1 Background 2 1.2 Objectives 2 1.3 Location 2 1.4 Catchment Description 2 1.5 Topography 3 1.6 Geology 3 2 QUALITATIVE DESCRIPTION OF FLOOD RISK 4 2.1 Sources 4 2.2 Pathways 4 2.3 Receptors 4 3 MODELLING APPROACH AND JUSTIFICATION 6 3.1 Modelling Approach 6 3.2 Modelling Limitations and Uncertainty 6 3.3 Model Accuracy and Appropriateness 6 3.4 Model Verification 6 4 INPUT DATA PLAN 7 4.1 Data Used 7 4.2 Data Quality 7 4.3 Data Uncertainties 7 4.4 Previous Studies 8 5 TECHNICAL METHOD AND IMPLEMENTATION 9 5.1 Hydrology 9 5.2 Hydraulic Modelling 9 5.2.1 Surface Water Modelling 10 5.2.2 Fluvial Modelling 11 5.3 Modelling Results Post-processing 13 6 MODEL PROVING 14 6.1 Run Performance 14 6.1.1 Surface Water Model 14 6.1.2 Fluvial hydraulic model 14 6.2 Model Calibration and Verification 14 6.2.1 Surface Water Model 14 6.2.2 Fluvial hydraulic model 15 6.3 Sensitivity Analysis 15 7 MODEL RESULTS 16 7.1 Model Runs 16 7.2 Model results and flood risk summary 17 8 LIMITATIONS 22 8.1 Model Shortcomings 22 8.2 Model Improvements 22 8.2.1 Surface Water Model 22 8.2.2 Fluvial Model 22 8.3 Further Uses for the Model 23 9 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 24 EW FAS Teville Stream Hydraulic Modelling Report v01.doc ii Environment Agency EW FAS Teville Stream Model Build Report November 2011 Appendices Appendix A – Model User Report Appendix B – Tabulated -

Nursery-Leaflet.Pdf

Why parents say they chose Sompting Abbotts Preparatory School for their child Why do we like Sompting Abbotts? The grounds, relaxed “atmosphere and sense of adventure created by the school. Plus, children are actually allowed to climb trees! ” “ We love the free wrap-around care (7.30am to 6pm). ” I knew the incredible grounds and outside country Education that future-proofs the magic of childhood “lifestyle would capture my children’s sense of fun and adventure. No other school in our area encourages den building, conkers and exploring copses. My children can now identify Sparrow Hawks and Buzzards; they know the sound of a Song Thrush and Blackbirds. ” Children are free to be children, while learning “ traditional values of empathy, respect and kindness. I like the traditional values and family feel. ” “The grounds are beautiful and give the children plenty of room to let off steam. Parking is easy for drop off. I liked that during our first visit we saw different children working on different things Children learn more quickly in their early within a class, depending on ability. “ years than at any other time ” Testimonials reproduced from Sompting Abbotts 2017 School-wide ” Parent Satisfaction Survey Our youngest pupils join the Early Years Foundation Stage and stay in our nursery until Reception Year. Sompting Abbotts Nursery They enjoy an exciting play-based When they’re ready, they take their first curriculum, with a mix of child- and steps in learning to read and write. We’ll teacher-led activities. Our Nursery introduce your child to phonics, reading children have a weekly singing lesson with and number and topic-based learning. -

DIRECTIONS from the East and North East

DIRECTIONS From the East and North East From the M25 (clockwise), exit at J7 (M23/A23) towards Gatwick and Brighton. Continue south along the M23/A23 toward Brighton for approximately 30 miles. At the roundabout, take the left lane for the slip road, joining the A27 (Worthing) About a mile beyond the Southwick Tunnel on the A27, there is a three lane traffic light intersection (opposite Shoreham Airport). Take the right hand slip road at the traffic lights signposted to Lancing College. From the North West From the M25 (anti-clockwise), exit at J9 (A243 Leatherhead/A24 Dorking) towards Dorking. Follow the A24 south for approximately 30 miles, until you reach the Washington roundabout. Take the first exit left signposted A283 Steyning and Bramber. Stay on the A283 for five miles until you reach the roundabout under the A27 flyover. Take the second exit marked A27 Worthing. On joining the A27, immediately take the right hand lane. You will come to a three lane traffic light intersection (opposite Shoreham Airport). Turn right at the traffic lights signposted to Lancing College, into Coombes Road. From the West Follow the A27 through Arundel and Worthing. 3 miles east of Worthing, approximately half a mile after the Lancing Manor roundabout on the A27, you will come to a three lane traffic light intersection. Turn left at the traffic lights signposted to Lancing College, into Coombes Road. ALL TRAFFIC From Coombes Road Drive 200m and take the first turning on the left. After 100m turn right into the College Drive - signposted. The Pavilion is a thatched building halfway up the drive on the right. -

155 04 SD397 NEECA 2 Schedule 19 Appendix A

Project Title: East Worthing FAS – Teville Stream Hydraulic Study Project Number: IMSO001181 Project Stage: Initial Assessment Environment Agency Project Manager: Contact Details for EAPM: Address: Telephone: E-mail: BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF PROBLEM: The Teville Stream lies within the town of Worthing, West Sussex. The River Adur Catchment Flood Management Plan (Capita Symonds, 2008) identified possible areas of flood risk, but did not carry out broadscale modelling of the catchment and instead based it’s assessment of risk on the Flood Zone maps. The CFMP states that the current baseline is insufficient to appropriately determine fluvial flood risk within the system. This project seeks to accurately determine the level of fluvial flood risk within the Teville Stream catchment area. The catchment is densely populated with much of the upper area being culverted and integrated with the surface water of the town. The semi-natural part of the upper watercourse is not very well defined, having several tributary streams and agricultural drainage channels. The main channel is a mixture of culverts and open sections, running under and alongside a pharmaceutical works, an industrial estate, historic landfill sites, a public amenity tip and a sewage works, finally emerging in an open channel which enters Brooklands Lake, a public leisure facility/boating lake occupying the area of the former tidal basin. This freshwater lake is maintained artificially by a terminal control structure at the seaward end, which drains into the sea after passing under the A259 seafront road. Flow from the north is augmented by runoff from the A27 highway and is discharged from a retention structure constructed on one of the tributaries. -

TARRING FLOOD ACTION GROUP Rain Garden Proposals

Active Community Fund GRANT APPLICATION FORM Section D: Your funding application Community Group Tarring Flood Action Group SuDs retro solutions to surface water flooding Project Title recommendations from earlier Feasibility study. Description of issues, needs and/or initiatives Within the West Tarring Conservation Area (See attached supplementary paper -map Appendix 1) there are a number of areas that large amounts of water collects on a regular basis, and more importantly, there have been a number of occasions in the recent past (2000, 2012) when flash floods have badly affected the area, resulting in flooding of, and damage to, a number of residential and commercial properties. Tarring High Street, in the conservation area, has had several floods in recent years and old buildings at the south end of the street and at the north end of South Street / Priory Close have suffered in particular. Following discussions at a TFAG Multi-Agency Meeting, the general consensus is that the floods were caused by a number of contributing factors:- • Climate Change impacting on localised intensity of rainfall • An inability of the network of drains and gullies to cope with heavy downpour events • Blocked drains and gullies • An aging, predominantly combined, surface water and sewage system • Discharge of roof water directly on to pavements/roads • Bow-wave surges caused by uncontrolled through-traffic • The influence of the Teville Stream and its confluence with Broadwater Brook, although this factor is subject to debate. • The lack of empirical data on problem areas of pooling and flooding in the Worthing area. • The dominance of a hard landscape and the lack of any ‘natural’ means of absorbing excessive rainwater before it can develop into flooding. -

Worthing Core Strategy?

Core Strategy April 2011 Foreword Foreword This Core Strategy was adopted by Worthing Borough Council on 12th April 2011. The document, part of the Local Development Framework (LDF), will help guide planning and development in the Borough for the next 15 years and will be used to inform decision making on all planning applications. Regeneration is the key focus of the document with the strategic development at West Durrington and 12 areas of change identified as major regeneration opportunities. The Core Strategy also outlines how development needs will be met with a series of policies on key issues such as housing, employment, retail and environmental protection. An independent examination of the plan was carried out and the Inspector concluded that, ‘There is a clear vision at the heart of the Core Strategy of a thriving, prosperous and healthy town that plays a central role in the wider sub region.’ The document is the result of a number of years of preparation and consultation and we are really pleased that all the hard work has paid off and the Inspector has approved our plan and has confirmed it is deliverable. The Core Strategy is incredibly important, as it helps us work towards delivering a thriving and stronger Borough. Bryan Turner Cabinet Member for Regeneration Adopted Core Strategy April 2011 1 Foreword 2 Adopted Core Strategy April 2011 Contents Section A - Introduction, Context and Vision 1 Introduction 6 2 Characteristics of the Borough 12 3 Issues and Challenges 20 4 The Vision and Strategic Objectives 32 Section B - -

Sompting Court, St. Giles Close, Shoreham-By-Sea, BN43

SHOREHAM OFFICE 31 Brunswick Road, Shoreham-By-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5WA Tel. 01273 441341 [email protected] Sompting Court, St. Giles Close, Shoreham-by-Sea, BN43 6GY | £225,000 2 Double Bedroom First Floor Flat Large 21' Double Aspect Lounge Diner Modern Fitted Kitchen Modern Fitted Bathroom Ideal For First Time Buyers And Investors Pvcu Double Glazed Windows Long Lease And Low Maintenance Close To Local Shops And Amenities Viewing Is Advised Popular Residential Location JACOBS STEEL Are Delighted To Offer For Sale This Communal front door through to:- Deceptively Spacious 2 Double Bedroom First Floor Flat In This Popular Residential Location Benefiting COMMUNAL ENTRANCE HALL: From A Large 21' Double Aspect Lounge Diner And Stairs to:- Modern Fitted Kitchen. FIRST FLOOR LANDING: Conveniently situated off Middle Road, being on level Private front door through to:- ground and within easy walking distance of local shops and schools. The centre of Shoreham, with its more 'L' SHAPED ENTRANCE HALL: comprehensive shopping facilities, health centre, Comprising cupboard housing factory lagged emersion library and mainline railway station, is just under 1 heater with slatted shelving, further cupboard with mile away. shelving, directable ceiling spotlights, further cupboard with hanging rail and shelving, door through to:- SPACIOUS DUAL ASPECT LOUNGE DINER: 21' 0" x 11' 10" (6.4m x 3.61m) East and South aspect. Comprising two pvcu double glazed windows, TV point, telephone point, directable ceiling spotlights, doors through to:- MODERN KITCHEN: 11' 10" x 7' 4" (3.61m x 2.24m) West aspect. Comprising pvcu double glazed window, roll edge laminate work surfaces with cupboards below, matching eye level cupboards, inset one and a half bowl stainless steel drainer sink unit with mixer tap, inset four ring ceramic hob with matching oven below and extractor over, built in fridge/ freezer, built in "Hotpoint" washing machine, tiled splashbacks, directable ceiling spotlights. -

The Lingerie Salesmen

The Lingerie Salesmen Gary chases his dream job, to become a sales rep for a lingerie wholesaler. The story is set in 1968. 1 | P a g e As Gary Jones sat in the hotel restaurant in Norwich eating his steak and chips he reflected on what had been a good week so far for sales. It was a Thursday night in October 1968. He had secured several big orders from customers in his patch. He had been on the road for three days and was looking forward to getting home and seeing his wife in Peterborough tomorrow. Perhaps he might sit at the bar for a drink after dinner. There only seemed to be one other man at the bar, nursing a beer. Nine months ago, he had been working for a tractor dealer in Peterborough. Sometimes he had to travel round Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire and Norfolk, selling spare parts. Although he was a successful salesman he found it slightly dull. He had been looking for a new job that paid bonuses based on sales as he knew he would make more money that way. It was his wife who had pointed out the advert in the local paper for a sales rep for a local firm, called Webbers. He had seen the ad but had skipped over it. The sales rep would be selling women’s lingerie and hosiery to department stores and family run businesses anywhere in the UK. Although the firm was also based in Peterborough it would probably mean being away from home most weeks. “But I don’t know anything about women’s clothes, “he said in protest. -

Part C Infrastructure Delivery Plan

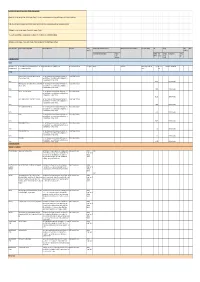

Residential and or Employment / Commercial use - PDL Sites: Durrington Station 8) Martlets Way - Developer Capacity = 50 units - Realistic Capacity = 50 units. The site also has potential to accommodate 12,000 sqm of office floorspace and 12,000 sqm of industrial space. 9) HMRC Offices, Barrington Road - Developer Capacity = 500 units - Realistic Capacity = 150 units. The site could potneitally accommodated complementary employment. 10) Worthing Leisure Centre - Developer Capacity = 160 units - Realistic Capacity = 160 units * Please note that a windfall allowance / extant planning permissions figure of 2,967 residential units have been identified for the Borough Total Residential - Developer Capacity = 710 units - Realistic Capacity = 360 units Total Employment / Commercial floorspace = 24,000 sqm Scheme / Project Name Scheme description including location Reason for improvement Delivery Lead Delivery Importance to the Local Plan / Prioritisation Status of scheme as at 17 / 18 and commitment Delivery time / phasing Cost Funding Risk / Notes Partner(s) Contingency Critical (C) Essential (E) Desirable (D) Requires Estimated Cost Estimated Funding sources Funding further total Cost reference funding gap information available SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE HEALTH Improvements to Primary Provision of additional Primary Care healthcare facilities at 1 or more GP Required to meet demand arising from development NHS Coastal West Sussex CCG NHS England Critical (C) New schemes Phasing will depend on housing 420,744 NHS health 420,744 Developer contribution 0 Care healthcare facilities surgeries according to patient choice delivery tariff POLICING Officer start-up costs (work stations, radios, protective equipment, The impacts of the proposed quantum of development in the borough is so Police and Crime Commissioner uniforms and bespoke training). -

Sompting Conservation Area Report

~a■' IMPORTANT -AMENDMENT TO $pUNDARY At its meeting on 24th November 1992, Adur District Council amended the boundary of Sompting Conservation Area. The new Conservation Area boundary is shown on the map inserted inside the front cover. ~ `~ ~ ~ ~ '~ ♦ ~ ~ ~;~; Eo r' 'd~~d NOIld~~3SN0~ ~NI1dWOS <' u ~ ~~~ ~~ ~ ~ Q~ ~~ Oa' V Qi :' ~~• .~` f,r ,r ., ~.~ ...~ ... _ ,o ~ ~.._~:—^'`~`~~'yn• .... `~• ~ :l:tuU3LL.......uw::li:.nu:iliG:iu:ULiI::~~.:::::•~ ........... ... :~:.+ d w 't'Vl {~t~.......f...........:nu .s •.....M o O wiles w~~ uu .. .... ... i i t ~ ~ ~'~ ~ ° „~i,., ~~er. ~ .0 .... f o I O i •• ' i.::;;fi:;;W;i(~ ; ~,.~...rw'~ n •. i ~ ~ ~ MMrf i j Kiwi "~!~~ .' Y~. •. ~Y1 ,.. ~ ~ r~~~ O O !r+r Sy~~ ..~:t ~... Va%'~ ~, ~NJI•'' ...... ' .. ' 7 _~_ - I~ s~ '~, O win .~ '~~ O ~ S ^-:r-zzs.a.~..~~~~ ~ '~[~ ~ 1 ~ ~ •' ~~ f l..i.^' .Y~ t w,..• «.w~e'~I, DSO ~.1.. i w. ~7 _ o ~M, ~~ ~5.~ w~~."'~ ~ ~~~~ •~.~_1 ~',, insaeasas::as :ui:1 ",~ ' !~~{ ~ ~ _ ~ ,~~' Oo n1. ~ v Z= y ai ~r \0 ~ ° '''' ~1-'i !: ~ .................. V r i ~. .S: n t ~r ~1. ~u~1wM ` /~w^.Y i`^T"11 :~ ~:~~ l t 'I, ~~'~~~ii ' 1 ~ C ~ ~{ _ ~~ w • p - f t i O O o O ., ~r~~ i Yt2 f ~.u~ b ~ ~O O e 7 e _ ~ ..... ~~~o O r . ...-~.--. _. _. ,.. .r___. ~ ... ... •,:. •. •" i r i ~ y.•o ..... I r O O 0 O 9 ..••' 7 O O O 7 O O C '`~ ~ i1i .. *t ~ ~ o ...8 . _ i ~ ? o +~'''r ~!,~.~`' `.f:t cP n------~j-db _--~-~__ P p 0 ~ O ...M K,{..:.U~y4~ ;.i ~wwnr ~ ~.. ~` ':•~ ~ i• i0 ... ;..,. iii •-..,_ .. .... '...• ., ~; .. ......~• rt L, ..- .