Documentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kent County Rugby Football Union Limited

Kent County Rugby Football Union Limited 2018-2019 Handbook President John Nunn Contents The Rules of Kent County Rugby Football Union Ltd 3 Kent County RFU Structure 5 Officers & Executive Committee 6 Sub Committees 7 RFU Staff 10 Representatives on Other Committees 11 County Committee Meetings 11 Kent Society of Rugby Football Union Referees Limited 12 Important Dates 13 Men’s Leagues 14 Women’s Leagues 16 RFU Principal Fixtures for Season 17 County Fixtures 18 County Mini & Youth Festivals 19 Shepherd Neame Kent Competitions 20 Competition Rules & Regulations 21 Member Clubs 25 Club Internet Directory 26 Associates of KCRFU 27 Sponsors 34 Partners 37 2 The Rules of Kent County Rugby Football Union Ltd Registered under the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014 (Register Number: 29080 R) are printed separately and each Member and Member of Committee has copy available for inspection. Reg. Office, Leonard House, 5-7 Newman Road, Bromley, Kent BR1 1RJ CONSTITUENT BODY RESOLUTIONS 1. The Annual Subscription of this Union shall become due on the 31st October in every year and shall be: £50 for Members £10 for Individual Associates £20 for Associated Clubs £250 for Corporate Associates (any member failing to pay the subscription by 1st November shall cease to have a vote for any purpose whatsoever in accordance with Rule 5.8.1.) 2. The County uniform shall consist of a dark blue jersey with the County Badge in white on the left breast, dark blue shorts and dark blue stockings with light blue tops and shall be worn by players in County Match- es. -

HRC A4 Playoff Match 21.04.2018 New.Indd

Season 2017-2018 // 21st April 2018 LONDON 2 SOUTH FOR PROMOTION TO LONDON 1 SOUTH HOVE V OLD REIGATIAN SATURDAY 21ST APRIL 2018 THIS YEARS PLATINUM SPONSORS: HOVE RECREATION GROUND @HoveRugbyClub SHIRLEY DRIVE, HOVE THANK YOU TO ALLTHANK OUR SPONSORS YOU TO ALLTHANK OUR SPONSORS YOU TO ALL OUR SPONSORS www.hoverugby.club If you are interested in becoming a sponsor of Hove Rugby Club call 01273 505103 If you are interested in becoming a sponsor of Hove Rugby Club call 01273 505103 www.hoverugby.club If you are interestedwww.hoverugby.club in becoming a sponsor of Hove Rugby Club call 01273 505103 If you are interested in becoming a sponsor of Hove Rugby Club call 01273 505103 PRESIDENT’S & CHAIR’S ADDRESS Just when you thought it was all Congratulations to both Hove over – it isn’t! Last week it seemed and Old Reigatians on achieving a racing certainty that, even if we runners up position in London won and qualifi ed for the end of South East 2 and London South season play off in second place West 2 respectively and with it (London and South East Division the opportunity for promotion to 2) the play off would be an away London 1 in this winner takes all fi xture. Instead Old Reigatian lost play off fi xture. (30-29) away to London Exiles, we Richard Hopkins won and gained a bonus point, all David Forsyth We can anticipate a hard fought of which leads to this afternoon’s and competitive game between 2 eliminator for promotion back to London 1 South after a three teams that share the distinction of having the second fewest season absence. -

Kent County Rugby Football Union Limited

Kent County Rugby Football Union Limited 2019-2020 Handbook President John Nunn Contents The Rules of Kent County Rugby Football Union Ltd 3 Kent County RFU Structure 5 Officers & Executive Committee 6 Sub Committees 7 RFU Staff 10 Representatives on Other Committees 11 County Committee Meetings 11 Kent Society of Rugby Football Union Referees Limited 12 Important Dates 13 Men’s Leagues 14 Women’s Leagues 16 RFU Principal Fixtures for Season 17 County Fixtures 18 County Mini & Youth Festivals 19 Shepherd Neame Kent Competitions 20 Competition Rules & Regulations 21 Member Clubs 25 Club Internet Directory 26 Associates of KCRFU 27 Sponsors 34 Partners 37 2 The Rules of Kent County Rugby Football Union Ltd Registered under the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014 (Register Number: 29080 R) are printed separately and each Member and Member of Committee has copy available for inspection. Reg. Office, Leonard House, 5-7 Newman Road, Bromley, Kent BR1 1RJ CONSTITUENT BODY RESOLUTIONS 1. The Annual Subscription of this Union shall become due on the 31st October in every year and shall be: £50 for Members £10 for Individual Associates £20 for Associated Clubs £250 for Corporate Associates (any member failing to pay the subscription by 1st November shall cease to have a vote for any purpose whatsoever in accordance with Rule 5.8.1.) 2. The County uniform shall consist of a dark blue jersey with the County Badge in white on the left breast, dark blue shorts and dark blue stockings with light blue tops and shall be worn by players in County Match- es. -

Kent County Rugby Football Union Limited

Kent County Rugby Football Union Limited www.kent-rugby.org President Hon. Secretary Hon. Treasurer J Nunn Mrs. S C Taylor P.J. Dessent [email protected] Notice is hereby given that the Annual General Meeting will be held virtually, by a Zoom meeting on Wednesday 2nd September 2020, 7.00 pm registration for a 7.30 pm start. The members of the County Committee hope that you will be able to attend in this altered format. Agenda 1. Apologies for absence. 6. Election of Officers & Vice Presidents for 2020/21. 2. Minutes of the last AGM, held on 26th June 2019. 7. Election of Committee for season 2020/21. 3. Address of the President, who will propose the adoption of the Report. 8. Appointment of Auditors. 4. Minutes of the AFGM of 12th December 2019. 9. Any other business. 5. Proposed Rule Amendments – Paper attached. Report Executive Committee The work of the County Executive Committee in overseeing the finances and work programmes of the Kent RFU has - as with all of us - been disrupted by the season effectively concluding towards the end of March. This put paid to at least half of our programme of maintaining contact with our clubs which had been initiated with close to 50 clubs physically through our insight evenings in season 18-19. Despite this, communication we hope has continued to improve with our 70 clubs in full or associate membership in the County and we thank our Administration Manager, Tracy Pettingale, for the discipline around contributions and the presentation and content of our website which several other Counties have complimented us on and sought help to build similar sites. -

Crowborough Rugby Football Club

Crowborough Rugby Football Club 2015 Background . Recent OFSTED findings highlighted . the lack of competitive sport in schools, . the link between obesity and lack of exercise . the link between increased activity and increased concentration and academic achievements . 60% drop in time dedicated to organising school sports . Lack of specialist coaches in schools Mission Statement To provide free specialist rugby coaching to schools and clubs and to actively encourage more children to participate in rugby Plan . Establish and run a rugby development programme (Kids Active Rugby Initiative - KARI) delivered by a CRFC specialist rugby coach into 20 local schools & community groups running / facilitating after-school clubs & rugby lessons in school time . Introduce rugby and its core values to over 1,000 children in year 1 and 5,000 over 3 years Further information January 2015 Crowborough Rugby Football Club . Established in 1936 . 1,000 members . 450 players . 3 senior teams . 9 mini/junior teams . 50 qualified volunteer coaches across all age groups . Modern clubhouse, professionally run . Popular with local community for non rugby activities Our Core Values . Teamwork . Respect . Enjoyment . Discipline . Sportsmanship Club Objective . To deliver the core values in a safe, pleasant and welcoming environment for children of all ages, abilities and backgrounds Club Achievements . Awarded RFU Seal of Approval 2012 . Awarded Sussex Referees Fair Play trophy 2013 . 7 players have graduated from junior ranks to international honours . Dylan Hartley – Current full England player . Joseph Baines – England Deaf Rugby . Regular County representation at Junior / Colts and Senior level . 1st XV play in London 2 South East . Over 75% of current 1st team squad have come through the mini and junior ranks . -

A SHORT HISTORY the Club

MEDWAY RUGBY FOOTBALL CLUB – A SHORT HISTORY The club began life in 1929 as the Rolenian Sports Club when pupils at the Kings School started playing hockey and cricket to occupy themselves during the long school holidays. They rented a pitch at Priestfields from the headmaster of Allendale Prep School at a nominal rental of £4 per annum. There they built a small pavilion which was officially opened in March 1928. It was extended in 1931 when "fixed concrete plunge baths and showers were added for the rugger." Saturday 10th October 1931 saw the club play its first match when they played and beat the King's School 10-5 at the Paddock in Rochester. Interestingly Ronald Buxton, the club captain was also the school captain at the time but there is no record of which team he played for on the day. (Right) The Paddock in Rochester At the end of that season the Chatham Observer reported "the Easter Saturday fixture between the Old Williamsonians and the Rolenians, the newly formed Rochester rugby football club, on the former’s ground, aroused much local interest, a large crowd watching a thrilling game". The visitors won by 9 points to nil with the captain scoring twice. Over the next few years the club grew at pace and by the outbreak of the WW2 were running three sides and a Wednesday XV and were the only open club in the Medway towns. United Services (Chatham), Shorts Brothers (the aeroplane manufacturers), the Old Williamsonians and the Old Anchorians being the others at the time. -

TOUCHLINE JUNE 2011.Fm

STOP PRESS The draw for Round 1 of the Kent Cup has been made. Maidstone have a bye into Round 2 where they will host the winners of the tie between Sevenoaks & Medway. Annual Dinner & Awards Night...32 / Club Blazer Update...32 INSIDEBob Beney....1 / Andy Golding...3 / Andy Foly...5 / Bob Hayton’s Ups & Downs...7 / Senior XVs Reports...11 / Des Diamond - Coaching Notes...17 Carol McKenzie’s House Report...18 / Youth Section News...19 / Junior Sides’ Reports...20 / Club Shop...26 / Website News...28 / Sponsorship News...30 President’s Piece Bob Beney - Making Changes What a Season! My first year as president has certainly had many peaks and troughs. From a very sad personal beginning to a mid-table finish and then to be relegated and so on. Following the club’s final meeting with the RFU, we both agreed that it is in all our interests to move on from the eye incident. We are now putting a firm line in the sand. Looking positively forward I have some very good things to report. On the playing front we had a very commendable season. This is down to the efforts of new Director of Rugby, Andy Foley and his team. Everyone just wanted to play rugby, after all this is what we are, a rugby club. Andy has exciting plans for next season. The new flood lights have been to the benefit of all those that have been training and we have increased the playing area at the back of the first team pitch for the junior tag-rugby section. -

Sussex Fixture Bureau

SUSSEX FOOTBALL UNION HANDBOOK President Ken Nichols 2013-2014 S U Y S B SE G X RU SCHOOLS FOUNDED 1953 www.sussexrugby.co.uk Headline sponsors of Sussex Rugby Football Union www.shepherdneame.co.ukwwww..shepherdneame.co.uk SUSSEX RUGBY HANDBOOK CONTENTS GENERAL Affiliated Clubs contacts ..........................................................................................20 Appointments, Executive Officers, Representatives ..................................................8 CB Meetings and CB Fixtures ....................................................................................5 Child Safeguarding ..................................................................................................82 Club Code of Conduct ..............................................................................................3 County Coaches ......................................................................................................84 Community Rugby Development Team....................................................................79 COMPETITIONS County Championship Senior and U 20 ..........................................................70 Kick-off times ..................................................................................................37 National, London & SE League Fixtures ..........................................................45 Replacements ..................................................................................................68 Sussex Spitfire and RFU Knockouts................................................................39 -

Bishop's Stortford Rfc V Caldy

BSRFC OFFICIAL MATCH PROGRAMME THIS WEEKS FEATURES: NEW SEASON NEW CAPTAIN THE ROAD TO NATIONAL 1 THE NEW LAWS FOR THIS SEASON NATIONAL LEAGUE 1 BISHOP’S STORTFORD RFC V CALDY RFC £12 2 September 2017 Members £5 This beautiful programme has been produced using the very latest printing gizmos! It’s produced weekly... Designed Friday morning, Printed and finished Friday afternoon and in your good hands by Saturday lunchtime! Impressed? Give us a call to find out more 01279 757333 | proco.com - 2 - PRESIDENT’S WELCOME PERRY OLIVER WELCOME BACK TO SILVER LEYS FOR THE FIRST GAME OF THE 2017/18 SEASON AND OF COURSE OUR FIRST IN NATIONAL LEAGUE ONE. THE SUMMER, IF IT DESERVES TO BE CALLED THAT, SEEMS TO HAVE FLOWN BY BUT AT LEAST THE UNSEASONAL WEATHER HAS HELPED TUBBY WORK HIS MAGIC AND RESTORE ALL OF OUR PITCHES TO A1 CONDITION. I’d also like to extend a special welcome to the Thank you to everyone who helped us raise Players, Officials and Supporters of Caldy RFC the magnificent amount of £8374.43 for last on this first time our clubs would have met, and season’s Presidents Charity ‘Ellies Fund’. of course everyone associated with our Match This season we have decided to make The Day sponsors –Tees & Match Day Experience Essex & Herts Air Ambulance our club charity. sponsors - Russell Partnership. On the final weekend of last season as we Like ourselves, Caldy are new to National One. were all celebrating promotion and the Blues Like us they were promoted as Champions of winning the County cup, we learnt that one their National 2 league – the North, failing to of our youth players had sustained a serious win only 3 of their 30 games. -

Charlton Park V Medway Charltonpark

Charlton Park v Medway Saturday 12 April 2014 3pm charltonpark.org.uk ACTIVE CLUBMARK is the SPORT ENGLAND mark of high quality junior clubs ACCESSIBLE ACCREDITED Welcome am delighted to welcome you all here for the final Vice President’s Lunch of the 2013-14 season. Our guests today are Medway RFC. Medway are a strong and popular club within London 2 South East and deservedly so. Certainly, they have always welcomed ICharlton Park RFC to their ground in the Medway Towns, in a typical rugby manner - fierce and fair competition on the field, with good companionship and friendship afterward. Since their formation on 1947 they have improved and maintained their fixture list and are now justifiably a vital and strong club in this quadrant of the London Division. Both clubs have performed well this season, with Medway, lying third in the league having beaten second placed Maidstone twice. We at Charlton Park are very grateful for that, as, barring any clerical errors or untoward penalty points that we may accrue in my worst nightmares, we are the league champions. However, please do not let anyone think that this is a game which has no competitive edge, I have it from Mark Marriott, now Vice Chairman of Medway, that they are out to win today and we would not expect it any other way We are also delighted to welcome an ex-President of Kent, John Carley, who has agreed to present the winners plaque for London 2 South East, after the game, John has been a great friend to Charlton Park and indeed to Kent rugby and we are delighted to see him here once more. -

Fixtures and Results

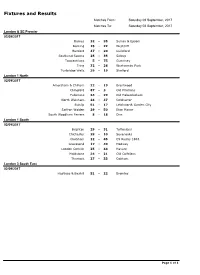

Fixtures and Results Matches From: Saturday 02 September, 2017 Matches To: Saturday 02 September, 2017 London & SE Premier 02/09/2017 Barnes 32 - 35 Sutton & Epsom Dorking 15 - 22 Westcliff Hertford 47 - 20 Guildford Southend Saxons 25 - 35 Sidcup Towcestrians 5 - 75 Guernsey Tring 32 - 26 Westcombe Park Tunbridge Wells 39 - 19 Shelford London 1 North 02/09/2017 Amersham & Chiltern 22 - 19 Brentwood Chingford 87 - 3 Old Priorians Fullerians 34 - 29 Old Haberdashers North Walsham 24 - 37 Colchester Ruislip 51 - 17 Letchworth Garden City Saffron Walden 29 - 50 Eton Manor South Woodham Ferrers 8 - 18 Diss London 1 South 02/09/2017 Brighton 29 - 31 Tottonians Chichester 28 - 10 Sevenoaks Chobham 12 - 45 CS Rugby 1863 Gravesend 17 - 40 Medway London Cornish 25 - 44 Havant Maidstone 34 - 21 Old Colfeians Thurrock 27 - 33 Cobham London 3 South East 02/09/2017 Hastings & Bexhill 51 - 22 Bromley Page 1 of 1 Fixtures and Results Matches From: Friday 08 September, 2017 Matches To: Saturday 09 September, 2017 London & SE Premier 09/09/2017 Barnes - Tunbridge Wells Guernsey - Sutton & Epsom Guildford - Dorking Shelford - Hertford Tring - Towcestrians Westcliff - Southend Saxons Westcombe Park - Sidcup London 1 North 09/09/2017 Brentwood - South Woodham Ferrers Colchester - Diss Eton Manor - Chingford Letchworth Garden City - Fullerians North Walsham - Saffron Walden Old Haberdashers - Amersham & Chiltern Old Priorians - Ruislip London 1 South 09/09/2017 Cobham - Chobham CS Rugby 1863 - London Cornish Gravesend - Thurrock Havant - Brighton Medway - Old Colfeians Sevenoaks - Maidstone Tottonians - Chichester London 2 North East 09/09/2017 Ipswich - Epping Upper Clapton Norwich - Chelmsford Old Cooperians - Cantabrigian Romford & Gidea Park - Woodford Sudbury - Rochford Hundred Wanstead - Harlow London 2 North West 09/09/2017 Belsize Park - Chiswick Hackney - Hammersmith & Fulham Hampstead - Harpenden Harrow - Enfield Ignatians Hemel Hempstead - H.A.C. -

London & South East Fixtures 2020-2021

Round 1 05-Sep-20 Round 2 12-Sep-20 Round 3 19-Sep-20 Round 4 26-Sep-20 Round 5 03-Oct-20 Hertford v North Walsham Tring v Maidenhead Sidcup v Tring Maidenhead v Sidcup Hertford v Maidenhead Maidenhead v Wimbledon CS Stags 1863 v Hertford North Walsham v CS Stags 1863 Tring v Hertford CS Stags 1863 v Wimbledon Sidcup v CS Stags 1863 Wimbledon v Sidcup Hertford v Wimbledon Wimbledon v North Walsham North Walsham v Tring Tring v BYE BYE v North Walsham Maidenhead v BYE BYE v CS Stags 1863 Sidcup v BYE 1 conf 'A' Brighton v Havant Dorking v Tunbridge Wells Tunbridge Wells v Sevenoaks Sevenoaks v Dorking Dorking v Havant Westcombe Park v Dorking Havant v Sutton & Epsom Sutton & Epsom v Brighton Havant v Tunbridge Wells Westcombe Park v Sutton & Epsom 1 conf 'B' Sutton & Epsom v Sevenoaks Sevenoaks v Westcombe Park Westcombe Park v Havant Brighton v Westcombe Park Tunbridge Wells v Brighton BYE v Tunbridge Wells Brighton v BYE BYE v Dorking Sutton & Epsom v BYE BYE v Sevenoaks Round 6 10-Oct-20 Round 7 17-Oct-20 Round 8 24-Oct-20 Round 9 31-Oct-20 Round 10 07-Nov-20 Maidenhead vNorth Walsham CS Stags 1863 vMaidenhead North Walsham vHertford Maidenhead vTring Tring vSidcup Sidcup vHertford Wimbledon vTring CS Stags 1863 vSidcup Hertford vCS Stags 1863 CS Stags 1863 vNorth Walsham Tring vCS Stags 1863 North Walsham vSidcup Wimbledon vMaidenhead Sidcup vWimbledon Wimbledon vHertford BYE vWimbledon Hertford vBYE BYE vTring North Walsham vBYE BYE vMaidenhead Brighton vDorking Dorking vSutton & Epsom Havant vBrighton Tunbridge Wells vDorking Sevenoaks