Full Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Book (PDF)

M o Manual on IDENTIFICATION OF SCHEDULE MOLLUSCS From India RAMAKRISHN~~ AND A. DEY Zoological Survey of India, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkota 700 053 Edited by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA KOLKATA CITATION Ramakrishna and Dey, A. 2003. Manual on the Identification of Schedule Molluscs from India: 1-40. (Published : Director, Zool. Surv. India, Kolkata) Published: February, 2003 ISBN: 81-85874-97-2 © Government of India, 2003 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any from or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. • -This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher's consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. • The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price indicated by a rubber stamp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. PRICE India : Rs. 250.00 Foreign : $ (U.S.) 15, £ 10 Published at the Publication Division by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, 234/4, AJ.C. Bose Road, 2nd MSO Building (13th Floor), Nizam Palace, Kolkata -700020 and printed at Shiva Offset, Dehra Dun. Manual on IDENTIFICATION OF SCHEDULE MOLLUSCS From India 2003 1-40 CONTENTS INTRODUcrION .............................................................................................................................. 1 DEFINITION ............................................................................................................................ 2 DIVERSITY ................................................................................................................................ 2 HA.B I,.-s .. .. .. 3 VAWE ............................................................................................................................................ -

CONE SHELLS - CONIDAE MNHN Koumac 2018

Living Seashells of the Tropical Indo-Pacific Photographic guide with 1500+ species covered Andrey Ryanskiy INTRODUCTION, COPYRIGHT, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION Seashell or sea shells are the hard exoskeleton of mollusks such as snails, clams, chitons. For most people, acquaintance with mollusks began with empty shells. These shells often delight the eye with a variety of shapes and colors. Conchology studies the mollusk shells and this science dates back to the 17th century. However, modern science - malacology is the study of mollusks as whole organisms. Today more and more people are interacting with ocean - divers, snorkelers, beach goers - all of them often find in the seas not empty shells, but live mollusks - living shells, whose appearance is significantly different from museum specimens. This book serves as a tool for identifying such animals. The book covers the region from the Red Sea to Hawaii, Marshall Islands and Guam. Inside the book: • Photographs of 1500+ species, including one hundred cowries (Cypraeidae) and more than one hundred twenty allied cowries (Ovulidae) of the region; • Live photo of hundreds of species have never before appeared in field guides or popular books; • Convenient pictorial guide at the beginning and index at the end of the book ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The significant part of photographs in this book were made by Jeanette Johnson and Scott Johnson during the decades of diving and exploring the beautiful reefs of Indo-Pacific from Indonesia and Philippines to Hawaii and Solomons. They provided to readers not only the great photos but also in-depth knowledge of the fascinating world of living seashells. Sincere thanks to Philippe Bouchet, National Museum of Natural History (Paris), for inviting the author to participate in the La Planete Revisitee expedition program and permission to use some of the NMNH photos. -

Shell Working Industries of the Indus Civilization: a Summary

PALEORIENT, vol. 1011· 1984 SHELL WORKING INDUSTRIES OF THE INDUS CIVILIZATION: A SUMMARY J. M. KENOYER ABSTRACT. - The production and use of marine shell objects during the Mature Indus Civilization (2500-1700 B.C.) is used as a framework within which to analyse developments in technology, regional variation and the stratification of socio-economic systems. Major species of marine mollusca used in the shell industry are discussed in detail and possible ancient shelt"source areas are identified. Variations in shell artifacts within and between various urban, rural and coastal sites are presented as evidence for specialized production, hierarchical internal trade networks and regional interaction spheres. On the basis of ethnographic continuities, general socio-ritual aspects of shell use are discussed. RESUME. - Production et utilisation d'objets confectionnes apartir de coqui//es marines pendant la periode harappeenne (2500-1700) servent ;ci de cadre a une analyse des developpements technolog;ques, des variations regionales et de la stratification des systemes socio-economiques. Les principales especes de mollusques marins utilises pour l'industrie sur coqui//age et leurs origines possibles soht identifiees. Les variations observees sur les objets en coqui//age a/'interieur des sites urbains, ruraux ou cotiers sont autant de preuves des differences existant tant dans la production specialisee que dans les reseaux d'echange hierarchises et dans l'interaction des spheres regionales. Certains aspects socio-rituels de l'utilisation des coqui//ages sont egalement discutes en prenant appui sur les donnees ethnographiques. INTRODUCfION undeciphered writing system. The presence of cer tain diagnostic artifacts in the neighboring regions of Afghanistan, the Persian Gulf, and Mesopotamia In recent years the Indus Civilization· of Pakistan indicates that the Indus peoples also had contacts and Western India has been the focus of important with other contemporaneous civilizations. -

Biolphilately Vol-64 No-3

Vol. 67 (4) Biophilately December 2018 327 MARINE INVERTEBRATES Editor Ian Hunter, BU1619 New Listings Scott# Denom Common Name/Scientific Name Family/Subfamily Code AUSTRALIA 2018 August 1 (Reef Safari) (Set/5, SS/5, Bklts) 4827 $1 Chambered Nautilus, Nautilus pompilius Nautilidae A 4827a Bklt/4 (Sc#4827) (w/ white frames) (perf 14×14¾) 4832 SS/5 (Sc#4832a–e) (w/o white frames) 4832a $1 Chambered Nautilus, Nautilus pompilius Nautilidae A 4833 $1 Chambered Nautilus, Nautilus pompilius Nautilidae A 4836a Bklt/10 (3ea Sc#4833–34, 2ea Sc#4835–36) (die cut 11¼) (s/a) (w/ white frame) 4836b Bklt/20 (5ea Sc#4833–36) (die cut 11¼) (s/a) (w/ white frame) CARIBBEAN NETHERLANDS 2018 April 3 (Tropical Shells) (MS/4) (inscr. “Bonaire”) 97a 99c U/I shells (two shells-large shell on top) (also on Bot margin) U Z 97b 99c U/I shells (four shells) (also on Bot margin) U Z 97c 99c U/I shells (three shells) (also on Bot margin) U Z 97d 99c U/I shells (two shells-large shell on bottom) (also on Bot margin) U Z CARIBBEAN NETHERLANDS 2018 April 3 (Tropical Shells) (MS/4) (inscr. “Saba”) 98a 99c U/I shells (four shells-two on third row) (also on Bot margin) U Z 98b 99c U/I shells (four shells-zigzag pattern) (also on Bot margin) U Z 98c 99c U/I shells (two small shells) (also on Bot margin) U Z 98d 99c U/I shells (two large shells) (also on Bot margin) U Z CARIBBEAN NETHERLANDS 2018 April 3 (Tropical Shells) (MS/4) (inscr. -

Age and Growth of Muricid Gastropods Chicoreus Virgineus (Roading 1798) and Muricanthus Virgineus (Roading 1798) from Thondi Coast, Palk Bay, Bay of Bengal

Nature Environment and Pollution Technology Vol. 8 No. 2 pp. 237-245 2009 An International Quarterly Scientific Journal Original Research Paper Age and Growth of Muricid Gastropods Chicoreus virgineus (Roading 1798) and Muricanthus virgineus (Roading 1798) from Thondi Coast, Palk Bay, Bay of Bengal C. Stella and C. Raghunathan* Department of Oceanography and Coastal Area Studies, Alagappa University, Thondi Campus, Thondi-623 409, T. N., India *Zoological Survey of India, Andaman and Nicobar Regional Station, Haddo, Port Blair-744 102, Andaman & Nicobar Islands, India ABSTRACT Key Words: Muricid gastropods Age and growth of the Chicoreus virgineus (Roading 1798) and Muricanthus virgineus Chicoreus virgineus (Roading 1798) species were determined using different methods such as size Muricanthus virgineus frequency method, probability plot method and Von Bertalanffy’s growth equation. Using Palk bay Peterson’s method, male of Chicoreus virgineus was found to attain a maximum length of 7.25cm and the female a length of 10.2cm in the 4th year. In Muricanthus virgineus male and female attained a length of 8.5cm and 11.4cm respectively in 4th year. The results of probability plot method revealed that the male of Chicoreus virgineus reached a maximum length of 8.55cm, and the female 10.35cm in the 4th year. However, in Muricanthus virgineus, the maximum length of 9.4cm in male and 11.00cm in female were found in 4th year. Using Von Bertalanffy’s equation, Chicoreus virgineus male was found to attain a length of 8.85cm, and the female a length of 10.35cm while the male of Muricanthus virgineus calculated as 9.4cm, and the female 11.00cm of lengths in 4th year. -

Check List and Occurrence of Marine Gastropoda Along the Palk Bay Region, Southeast Coast of India

Available online at www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2013, 4(1): 195-199 ISSN: 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Check list and occurrence of marine gastropoda along the palk bay region, southeast coast of India Elaiyaraja C, Rajasekaran R* and Sekar V. Centre of Advanced Study in Marine Biology, Faculty of Marine Sciences, Annamalai University, Parangipettai, Tamil Nadu, India _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT The marine biodiversity of the southeast coast of India is rich and much of the world’s wealth of biodiversity is found in highly diverse coastal habitats. A present study was carried out on marine gastropod accessibility among Palk Bay region of Tamilnadu coastline to identify, quantify and assess the shell resources potential for development of a small-scale shell industry. A large collection of marine gastropod was made among the coastal line of Mallipattinam and Kottaipattinam found 61 species (25 families) of marine gastropods over a 12 months period from Aug- 2011 to July- 2012. A totally of 61 species belonging to 55 species of 40 genera were recorded at station 1 and 56 species belonging to 41 genera were identified at station 2. Most of the species were common in both landings centre with slight differences but some species like Turritella duplicate, Strombus canarium, Cyprae onyxadusta, Marginella angustata, and Harpa major were available in station 1 not available in station 2. The present study revealed that the occurrence of marine gastropods species along the Palk Bay region of Tamilnadu coastline. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Though marine science has established much attention in Tamilnadu coastline in the recent years, marine mollusks studies are still overseen by many researchers. -

A New Record of Morula Anaxares with a Description of the Radula of Three Other Species from Goa, Central West Coast of India (Gastropoda

www.trjfas.org ISSN 1303-2712 Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 12: 189-197 (2012) DOI: 10.4194/1303-2712-v12_1_22 PROOF SHORT PAPER A New Record of Morula anaxares with a Description of the Radula of Three Other Species from Goa, Central West Coast of India (Gastropoda: Muricidae) Jyoti V. Kumbhar1, Chandrashekher U. Rivonker2,* 1 National Institute of Oceanography (CSIR), Dona Paula, Goa, 403-004, India. 2 Department of Marine Sciences, Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa 403206, India. * Corresponding Author: Tel.: +91.832 6519352; Fax: +91.832 2451184; Received 10 February 2011 E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 18 October 2011 Abstract The present paper describes a new record of Morula anaxares (Kiener 1835) (Muricidae) from Goa, Central West coast of India aided by spiral cord ontogeny, aperture morphology of shell and SEM of radula. This species was previously reported from Andaman, Nicobar, Lakshadweep and Madras coasts. In addition, detailed structures of radula of other three species namely Orania subnodulosa (Melvill 1893), Semiricinula konkanensis (Melvill 1893) and Purpura bufo Lamarck 1822 from Goa are described for the first time using SEM photographs. Ke ywords: Muricidae, Goa, new record, taxonomic diagnosis, radula, SEM. Introduction (Yamamoto, 1997) and deposit large aggregates of egg masses to avoid predation. Further, their high The Muricidae (Gastropoda: Neogastropoda) is a densities coupled with a voracious feeding habit serve large group comprising almost 2500 Cenozoic and to regulate the population dynamics of diverse prey Recent species (Merle, 2005). Among the gastropods, such as corals, polychaetes, bivalves, chitons and this group exhibits highest degree of radiation with barnacles (Tan, 2003) and often endanger the prey regards to shell morphology and sculptural patterns, population. -

Common Molluscs of Gulf of Mannar

GOMBRT Publication No. 23 Empowered lives. Resilient nations. COMMON MOLLUSCS OF GULF OF MANNAR GULF OF MANNAR BIOSPHERE RESERVE TRUST RAMANATHAPURAM - 623 504 Tamil Nadu GOMBRT Publication No. 23 Empowered lives. Resilient nations. COMMON MOLLUSCS OF GULF OF MANNAR November 2012 Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve Trust Ramanathapuram - 623 504, Tamil Nadu, India Citation : Anbalagan, T. and V. Deepak Samuel 2012. Common Molluscs of Gulf of Mannar, Publication No. 23, 66 p. This Publication has no commercial value It is for circulation among various stakeholders and researchers November 2012 Compiled by Dr. T. Anbalagan Biodiversity Programme Officer Dr. V. Deepak Samuel Programme Specialist Energy & Environment Unit United Nations Development Programme Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve Trust Ramanathapuram - 623 504, Tamil Nadu, India Published by Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve Trust Ramanathapuram - 623 504, Tamil Nadu, India Typeset and Printed by Rehana Offset Printers, Srivilliputtur - 626 125 Phone : 04563-260383, E-mail : [email protected] GULF OF MANNAR BIOSPHERE RESERVE TRUST (GoMBRT) (A Stautory Trust of the Government of Tamil Nadu) S. Balaji, I.F.S. Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve Trust Chief Conservator of Forests and 102/26, Jawan Bhavan First Floor Trust Director Kenikarai Ramanathapuram - 623 503 FOREWORD Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve Trust, a State Government owned "Special purpose Vehicle" Agency, spearheads a movement of conservation of coastal and marine biodiversity in Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve Region, located in south eastern India. This Reserve has the richest faunal and floral repository in the entire South east Asia, in terms of both diversity and density, numbering about 4223 species. -

Radular Morphology by Using SEM in Pugilina Cochlidium (Gastropoda

Brazilian Journal of Biology https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.220076 ISSN 1519-6984 (Print) Original Article ISSN 1678-4375 (Online) Radular morphology by using SEM in Pugilina cochlidium (Gastropoda: Melongenidae) populations, from Thondi coast-Palk Bay in Tamil Nadu-South East coast of India Patricio De los Ríosa,b , Laksmanan Kanaguc , Chokkalingam Lathasumathic and Chelladurai Stellac* aDepartamento de Ciencias Biológicas y Químicas, Facultad de Recursos Naturales, Universidad Católica de Temuco, Casilla 15-D, Temuco, Chile bNúcleo de Estudios Ambientales, Universidad Católica Temuco, Casilla 15-D, Temuco, Chile cDepartment of Oceanography and Coastal Area Studies, Alagappa University, Thondi Campus, 623409, Tamil Nadu, India *e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: February 17, 2019 – Accepted: June 19, 2019 – Distributed: November 30, 2019 (With 8 figures) Abstract Radula in all melongeninae species is rather uniform and characterized by bicuspid lateral teeth with strongly curved cusps and sub rectangular rachidians, bearing usually 3 cusps. The aim of the present study was to describe the radula of 2 Pugilina cochlidium populations using SEM. The radula in 2 species proves itself as a rachiglossate type showing the radular formula of 1 + R + 1. The first population hasthe central tooth wide with sharp cusps equal in length, emanate from posterior margin of tooth base. The lateral teeth have 2 cusps and are long, sharp, pointed and bent towards the rachidian tooth. Whereas the second population, the central tooth is narrow with sharp cusps equal in length, emanate from posterior margin of tooth base. The lateral teeth have 2 cusps and are broad, longer, sharp, pointed and bent towards the rachidian tooth. -

An Analysis of the West Nggela (Solomon Islands) Fish Taxonomy

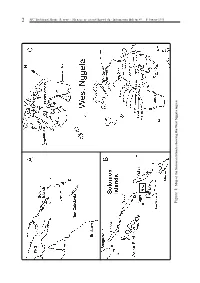

2 SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin #9 – February 1998 Map of the Solomon Islands showing West Nggela region Figure 1: Figure SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin #9 – February 1998 3 What’s in a name? An analysis of the West Nggela (Solomon Islands) fish taxonomy. by Simon Foale 1 Introduction Lobotidae, Gerreidae, Sparidae, Ephippidae, Chaetodontidae, Pomacentridae, Cirhitidae, Accurate knowledge about the behaviour, biol- Polynemidae, Labridae, Opistognathidae, ogy and ecology of organisms comprising marine Trichonotidae, Pinguipedidae, Blenniidae, fisheries is a vital prerequisite for their manage- Gobiidae, Microdesmidae, Zanclidae, Bothidae, ment. Before beginning any study on local knowl- Pleuronectidae, and Soleidae. edge of marine fauna, a working knowledge of The English names of many species of fish vary their local names must be obtained. Moreover, a quite a bit, even within one country such as great deal of local knowledge can often emerge in Australia. For most of the species listed in the very process of obtaining names (Ruddle, Appendix 1, I have used the English names given 1994). A detailed treatment of the local naming by Randall et al. (1990). For species not included in system of West Nggela marine fauna is given in Randall et al. (1990), names from Kailola (1987a, b, this paper. 1991) were used. Methods Results Local names of fish were collected by asking Appendix 1 contains 350 unique Nggela folk people to provide the Nggela names for fishes taxa for cartilaginous and bony fishes, together from photographs in books featuring most of the with the scientific (Linnean) taxa they correspond common Indo-Pacific species (Randall et al., 1990 to and, where available, a brief note describing an and Myers, 1991). -

A Review of Australian Helmet Shells (Family Cassididae— Phylum Mollusca)

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Iredale, T., 1927. A review of Australian helmet shells (family Cassididae— phylum Mollusca). Records of the Australian Museum 15(5): 321–354, plates xxxi–xxxii. [6 April 1927]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.15.1927.819 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney nature culture discover Australian Museum science is freely accessible online at http://publications.australianmuseum.net.au 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia A REVIEW OF AUSTRALIAN HELMET SHELLS (FAMILY CASSIDIDAE-PHYLUM MOLLUSCA) By TOM IREDALl~, Conchologist, The Australian Museum. (Plates xxxi-xxxii.) No connected account of the shells known as Helmet Shells has yet appeared in Australian literature, though many species have been listed by Hedley, Verco, May, Pritchard, Gatliff and Gabriel. The majority of these occur in temperate Australian waters, and many different inter pretations of the species exist. An attempt is here made to correlate the information available by means of the material gathered together in the Australian Museum, supplemented by loan of specimens from the workers above named, and to supply a criticism of literature. This review was begun some years ago and has proved of a very complex nature, both as regards the literary side and the conchological aspect. True Helmet Shells ,are common to the tropics, one or two species reaching into northern Australia, but in Australia, more numerously in the southern parts, many species of what may be termed" False Helmet" shells occur. Hitherto these two main groups have been commonly recognized, but sometimes only subgeneric rank has been allowed the latter. Many sub-groups have been accepted, but generally authors have differed as to the extent and nomination of these groups. -

Part 5. Mollusca, Gastropoda, Muricidae

Results of the Rumphius Biohistorical Expedition to Ambon (1990) Part 5. Mollusca, Gastropoda, Muricidae R. Houart Houart, R. Results of the Rumphius Biohistorical Expedition to Ambon (1990). Part 5. Mollusca, Gas• tropoda, Muricidae. Zool. Med. Leiden 70 (26), xx.xii.1996: 377-397, figs. 1-34.— ISSN 0024-0672. Roland Houart, research associate, Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Rue Vautier, 29, B-1000 Bruxelles. Key words: Rumphius expedition; Indonesia; Ambon; Mollusca; Gastropoda; Muricidae. This report deals with the species of Muricidae collected during the Rumphius Biohistorical Expedi• tion on Ambon. At 44 stations, a total of 58 species in 23 genera of the prosobranch gastropod family Muricidae were obtained. The identity and the classification of several nominal taxa is revised. Four species are new to science and are described here: Pygmaepterys cracentis spec. nov. (Muricopsinae), Pascula ambonensis spec. nov. (Ergalataxinae), Thais hadrolineae spec. nov. and Morula rumphiusi spec, nov. (Rapaninae). Some comments are included on the Muricidae described by Rumphius and on their identification. In his "Amboinsche Rariteitkamer" (1705) 21 species of muricids were included, of which 16 were illu• strated by Rumphius or Schijnvoet. The identity of those species is determined. During the Rumphius Biohistorical Expedition seven of these species have been refound. Introduction The Rumphius Biohistorical Expedition in Ambon (Moluccas, Indonesia) was held from 4 November till 14 December, 1990. The primary goal of the expedition was to collect marine invertebrates on the localities mentioned by Rumphius (1705). The general account, with a list of stations, was published by Strack (1993); it con• tains the history of the expedition and a detailed description of each station, with photographs.