Dsti/Eas/Ind/Wpia(2016)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

User Guide for the Envoy Data Link

User Guide for the Envoy Data Link SLC Doc Number UG-15000 Revision A 12335 134th Court NE Redmond, WA 98052 USA Tel: (425) 285-3000 Fax: (425) 285-4200 Email: [email protected] Preparer: Engineer: Program Manager: Quality Assurance: RESTRICTION ON USE, PUBLICATION, OR DISCLOSURE OF PROPRIETARY INFORMATION This document contains information proprietary to Spectralux Corporation, or to a third party to which Spectralux Corporation may have a legal obligation to protect such information from unauthorized disclosure, use, or duplication. Any disclosure, use, or duplication of this document or of any of the information contained herein for other than the specific purpose for which it was disclosed is expressly prohibited, except as Spectralux Corporation may otherwise agree to in writing. Spectralux™ Avionics Export Notice All information disclosed by Spectralux is to be considered United States (U.S.) origin technical data, and is export controlled. Accordingly, the receiving party is responsible for complying with all U.S. export regulations, including the U.S. Department of State International Traffic in Arms (ITAR), 22 CFR 120-130, and the U.S. Department of Commerce Export Administration Regulations (EAR), 15 CFR 730-774. Violations of these regulations are punishable by fine, imprisonment, or both. User Guide for the Envoy Data Link CHANGE RECORD APPROVAL/ PARAGRAPH DESCRIPTION OF CHANGE DATE REV Jenelle Anderson - All Initial Release July 31, 2019 All Updated with engineering feedback for terminology, implemented feeatured; Jenelle Anderson A deferred features are hidden. See ECO 15403 April 1, 2020 Document Number: UG-15000 Rev. A Page 2 of 173 User Guide for the Envoy Data Link TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... -

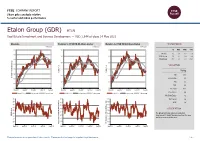

FTSE Factsheet

FTSE COMPANY REPORT Share price analysis relative to sector and index performance Etalon Group (GDR) ETLN Real Estate Investment and Services Development — USD 1.644 at close 14 May 2021 Absolute Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Sector Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Index PERFORMANCE 14-May-2021 14-May-2021 14-May-2021 1.9 150 150 1D WTD MTD YTD Absolute -0.5 -0.5 1.1 -5.0 1.8 140 140 Rel.Sector -1.2 3.1 2.8 -7.6 Rel.Market -1.6 0.9 0.4 -13.0 1.7 130 130 1.6 VALUATION 1.5 120 120 Trailing Relative Price Relative Price Relative 1.4 110 110 PE 45.3 Absolute Price (local currency) (local Price Absolute 1.3 EV/EBITDA 8.5 100 100 PB 0.7 1.2 PCF 3.4 1.1 90 90 Div Yield 10.4 May-2020 Aug-2020 Nov-2020 Feb-2021 May-2021 May-2020 Aug-2020 Nov-2020 Feb-2021 May-2021 May-2020 Aug-2020 Nov-2020 Feb-2021 May-2021 Price/Sales 0.4 Absolute Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Net Debt/Equity 1.0 90 90 90 Div Payout +ve 80 80 80 ROE 1.4 70 70 70 Share Index) Share Share Sector) Share - 60 - 60 60 DESCRIPTION 50 50 50 40 40 The Group's principal activity is residential 40 RSI RSI (Absolute) 30 30 development in Saint-Petersburg metropolitan area and Moscow metropolitan area. -

East Capital Sustainable Investment Report 2018

Sustainable investment report: ESG — a key tool for emerging and frontier market investments Sustainable investment report About East Capital East Capital is an independent asset manager Long-term specialised in emerging and frontier We focus on companies with long-term markets, founded in Sweden in 1997, with growth prospects and position our strategies offices in Dubai, Hong Kong, Luxembourg, to outperform their respective benchmarks Moscow, Oslo, Stockholm and Tallinn. We within three to five years. While we can make manage public equity funds, real estate funds some short-term adjustments, we do so with- and separate accounts, for a broad out sacrificing the overall long-term focus and international client base, including the low core turnover of the portfolios. leading institutions. Our investment strategy is based on in-depth Local company knowledge gained through Meeting frequently with company owners, proprietary fundamental analysis and management teams and policymakers is an frequent company meetings. We care fully integral part of the investment process. Such consider ESG-related risks and opportunities meetings give us in-depth local knowledge in our investment process, and favour that help us make better informed investment companies with long-term, sustainable decisions. growth prospects and responsible owners. Since day one, we have set out to be a long- Research-driven term, active and responsible investor. Over Diligent research is essential for identifying the years, our investment teams have key performance drivers and correctly interacted with thousands of companies, assessing risk. We rely on our own research, management teams, regulators, governments including risk scenarios and a proprietary and other investors. -

And Ground-Based CO Total Column Observations Over 2010 Russian Fires

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 7925–7942, 2011 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/11/7925/2011/ Atmospheric doi:10.5194/acp-11-7925-2011 Chemistry © Author(s) 2011. CC Attribution 3.0 License. and Physics Satellite- and ground-based CO total column observations over 2010 Russian fires: accuracy of top-down estimates based on thermal IR satellite data L. N. Yurganov1, V. Rakitin2, A. Dzhola2, T. August3, E. Fokeeva2, M. George4, G. Gorchakov2, E. Grechko2, S. Hannon1, A. Karpov2, L. Ott5, E. Semutnikova6, R. Shumsky2, and L. Strow1 1Joint Center for Earth Systems Technology, University of Maryland Baltimore County, Baltimore, MD, USA 2Obukhov Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Moscow, Russia 3EUMETSAT, Darmstadt, Germany 4UPMC, Univ. Paris 06, Univ. Versailles St-Quentin, CNRS/INSU, LATMOS-IPSL, Paris, France 5NASA, Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, USA 6Mosecomonitoring, Moscow, Russia Received: 18 March 2011 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 19 April 2011 Revised: 22 July 2011 – Accepted: 1 August 2011 – Published: 4 August 2011 Abstract. CO total column data are presented from three 1 Introduction space sounders and two ground-based spectrometers in Moscow and its suburbs during the forest and peat fires Carbon monoxide (CO) is recognized as a useful tracer of that occurred in Central Russia in July–August 2010. Also biomass burning and anthropogenic pollution (Logan et al., presented are ground-based in situ CO measurements. The 1981; Edwards et al., 2004, 2006; McMillan et al., 2010). Moscow area was strongly impacted by the CO plume from CO total source is estimated by Holloway et al. (2000) as these fires. -

Organizing Bicycle Traffic in Moscow to Reduce Air Pollutant Concentrations

E3S Web of Conferences 164, 04007 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf /202016404007 TPACEE-2019 Organizing bicycle traffic in Moscow to reduce air pollutant concentrations Igor Pryadko1,* 1 Moscow State University of Civil Engineering, 129337, 26 Yaroslavskoye sh., Moscow, Russia Abstract. The objective of this article is to assess the prospects for development of cycling as a mode of transport in major cities in Russia and worldwide. Towards this end, the author addresses bicycle traffic organization patterns in the cities of Europe, South Eastern Asia and South America. The methods, employed in this research project, include sociological data collection, or the polling of urban residents (residents of the Russian capital), the retrospective analysis of sources, including news articles, the comparative historical method and forecasting. In the article, the impact produced on the urban environment, namely, on the surface layers of the urban atmosphere, by the motor traffic is compared with the one produced by the bicycle traffic. The mission of this research project is to analyze development of cycling network routes, parking lots, and accompanying small architectural forms in Moscow. The author employs methods of environmental monitoring to assess the impact produced by the motor transport on the environmental situation in the city. The conclusion is that there is a need to develop the urban walking infrastructure, to expand the urban cycling network, and to convert to the biosphere compatible urban transport. 1 Introduction More often than not urban planners and architects face the challenge of limiting pollutant emissions caused by human economic activities and designing a clean and biosphere compatible urban space. -

Franco-Russian Decentralized Cooperation Year 2021

1 19 March 2021 The French and Russian Governments have decided to make 2021 a “Franco-Russian Decentralized Cooperation Year”. The aim of this Year is to bring a new perspective in each country on the other, to give new impetus between French and Russian cities and regions, to strengthen ties between French and Russian citizens, and to highlight the assets and diversity of our respective territories. The Franco-Russian Decentralized Cooperation Year will last throughout 2021 and end with the fifth “Franco-Russian meeting of local government bodies” in Russia (the last one took place in Nice in 2012). In the meantime, a number of events will take place in various parts of France and Russia, bearing the Year’s “label”. They will be organized either by local authorities themselves or by other local stakeholders, which may work with local government bodies. They may concern various fields, such as linguistic cooperation, exchanges for young people, sport, businesses, tourism, sustainable development, and cooperation between institutions. This document lists all the events held in the framework of the Franco-Russian Year. Published at the official launch of the Year on 19 March, it may later be updated with further initiatives. 2 19 March 2021 Events by theme: Theme: partnerships and twinning programmes .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Theme: Academic cooperation and research ................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Annual Report 2019

Annual Report 20 19 Beiersdorf worldwide 2019 1882 founded in Hamburg > 20,000 employees worldwide > 170 subsidiaries worldwide Beiersdorf products are available in nearly all countries worldwide 98 € 7,653 million patent applications Group sales in the Consumer Business Segment Production Locations Consumer Research & Development Locations Consumer Production Locations and Research & Development Locations Consumer Listed on the tesa Production Locations DAX since Corporate Headquarters 2008 As of: December 31, 2019 We are Beiersdorf At Beiersdorf we have been caring about segment, and LA PRAIRIE at the selective skin since 1882. Beiersdorf’s success is based cosmetics market. With its HANSAPLAST on its strong portfolio of internationally and ELASTOPLAST brands, Beiersdorf also leading brands. It is thanks to them that has a global presence in the field of plasters millions of people around the world choose and wound care. Renowned brands such Beiersdorf day after day. Our brands boast as LABELLO, AQUAPHOR, FLORENA, 8X4, innovative strength, outstanding quality, and HIDROFUGAL, GAMMON, COPPERTONE, exceptional closeness to our consumers. By ATRIX, FLORENA FERMENTED SKINCARE, responding quickly and flexibly to regional SKIN STORIES, and MAESTRO round off our needs, we are winning the hearts of con- extensive portfolio in the Consumer Busi- sumers in nearly all countries worldwide. ness Segment. Through the tesa brand, which Our successful skin and body care brands has been managed since 2001 by Beiersdorf’s form the focus of our successful brand independent tesa subgroup, we also offer portfolio and each brand serves very highly innovative self-adhesive system and different segments: NIVEA is aimed at the product solutions for industry, craft busi- mass market, EUCERIN at the dermocosmetics nesses, and consumers. -

City/Airport Country IATA Codes

City/Airport Country IATA Codes Aarhus Denmark AAR Abadan Iran ABD Abeche Chad AEH Aberdeen United Kingdom ABZ Aberdeen (SD) USA ABR Abidjan Cote d'Ivoire ABJ Abilene (TX) USA ABI Abu Dhabi - Abu Dhabi International United Arab Emirates AUH Abuja - Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport Nigeria ABV Abu Rudeis Egypt AUE Abu Simbel Egypt ABS Acapulco Mexico ACA Accra - Kotoka International Airport Ghana ACC Adana Turkey ADA Addis Ababa - Bole International Airport Ethiopia ADD Adelaide Australia ADL Aden - Aden International Airport Yemen ADE Adiyaman Turkey ADF Adler/Sochi Russia AER Agades Niger AJY Agadir Morocco AGA Agana (Hagåtña) Guam SUM Aggeneys South Africa AGZ Aguadilla Puerto Rico BQN Aguascaliente Mexico AGU Ahmedabad India AMD Aiyura Papua New Guinea AYU Ajaccio France AJA Akita Japan AXT Akron (OH) USA CAK Akrotiri - RAF Cyprus AKT Al Ain United Arab Emirates AAN Al Arish Egypt AAC Albany Australia ALH Albany (GA) USA ABY Albany (NY) - Albany International Airport USA ALB Albi France LBI Alborg Denmark AAL Albuquerque (NM) USA ABQ Albury Australia ABX Alderney Channel Islands ACI Aleppo Syria ALP Alesund Norway AES Alexander Bay - Kortdoorn South Africa ALJ Alexandria - Borg el Arab Airport Egypt HBH Alexandria - El Nhouza Airport Egypt ALY Alexandria - Esler Field USA (LA) ESF Alfujairah (Fujairah) United Arab Emirates FJR Alghero Sassari Italy AHO Algiers, Houari Boumediene Airport Algeria ALG Al Hoceima Morocco AHU Alicante Spain ALC Alice Springs Australia ASP Alldays South Africa ADY Allentown (PA) USA ABE Almaty (Alma -

Sustainable Development in Russia

Russian-German Environmental Information Bureau Russisch-Deutsches Büro für Umweltinformation Sustainable Development in Russia edited by Sergei Bobylev and Renat Perelet Sustainable Development in Russia Sustainable Development Sustainable Development in Russia edited by Sergei Bobylev and Renat Perelet Berlin–St. Petersburg 2013 Contents Forewords 4 1. Economic, political and institutional frameworks 1.1. Sustainable development and the “green economy” in Russia: the current situation, problems and perspectives | Sergei Bobylev, Renat Perelet 11 1.2. Legal Aspects: The state of legislation and legal practice | Ekaterina Khmeleva 18 1.3. Certifi cation and standardisation | Semyon Gordyshevsky, Yulia Grachyova, Anna Matyagina 22 1.4. Oversight and supervision of compliance with environmental legislation and environmental standards in the Russian Federation: a summary of judicial practice | Nina Popravko 28 2. Economic prerequisites for sustainable development and environmental economics 2.1. The energy sector in the context of sustainable development. Greening of the oil and gas sector problems and perspectives | Alexei Knizhnikov 37 2.2. Energy effi ciency: legislation, state policy and economic and business practice | Yevgeny Gasho, Maria Stepanova 42 2.3. Renewable energy: legislation, state support and business and civil society initiatives | Ivan Yegorov 52 2.4. The industrial sector and problems of economic development | Alexander Shabaldin 63 2.5. The waste management sector: the current situation, legislative framework, regional experience, perspectives and civil society initiatives | Marina Asadcheva, Anna Sycheva 70 3. Sustainable development of cities and regions 3.1. City and regional planning: problems of city growth, urban ecology, perspectives for sustainable urban development and civil society initiatives | Daniyar Yusupov 79 3.2. -

Investment Strategy of the City of Moscow for the Period up to 2025 (Updated Version)

Version of 2016 signed by the Mayor of Moscow Investment Strategy of the City of Moscow for the period up to 2025 (updated version) I. General provisions, principles, and sphere of application of the Investment Strategy of the City Moscow for the period up to 2025 .................................................... 2 II. Moscow’s Investment Declaration ..................................................................... 3 III. Specific features of implementing the Investment Strategy in 2016–2018 ...... 4 IV. Current status of investment activities, Moscow’s competitive positions and strategic investment policy goals ...................................................................................... 9 V. Trends in the development of the world and the global economy, and assessment of the factors determining Moscow’s investment appeal ............................. 11 VI. Investment policy tasks ................................................................................... 20 VII. The system of measures for implementing the Investment Strategy: systemic measures .......................................................................................................................... 21 VIII. Sector and territory priorities ....................................................................... 26 XI. System of measures for implementing the Investment Strategy: specific sector support measures ............................................................................................................. 31 X. Anticipated results -

Community Resilience and Vulnerability to Disasters: Qualitative Models and Megacities – a Comparison with Small Towns BORIS PORFIRIEV*

research paper Community resilience and vulnerability to disasters: Qualitative models and megacities – a comparison with small towns BORIS PORFIRIEV* Risk and Crisis Research Center at the Institute of Economics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Novocheriomushkinskaia, 42a 117418 Moscow, Russia This paper contrasts the resilience to disasters of megacities with small towns, using vulnerability as a key variable. As an instrument of this comparison a formal model of the communities’ vulnerability, further deconstructed into a set of specific modules, is developed and used. It is argued that the megacities’ high resilience capacity in the main ensures only a debilitating (although undoubtedly major) effect on them by disaster agents. Meanwhile, the impact on the small towns is often disastrous and sometimes turns into a real catastrophe with some communities totally devastated. However, this observation does not preclude some notable exceptions. To corroborate and highlight the key findings above, empirical data from the Russian experience of the late twentieth to early twenty-first centuries are provided, supplemented by some international illustrations. Keywords: natural hazards; disasters; vulnerability; resilience; megacities; small towns; models 1. Introduction and to the perception of the disaster/hazard by different communities can show important It is argued in the disaster literature that metropo- differences. litan regions with their large and rapidly growing This paper attempts to compare the resilience populations and concentration of wealth, to disasters of megacities and small towns using especially those located on the coastline or vulnerability as a key variable. To substantiate seismic zones, are most susceptible and worst the investigation and the proposition about hit by disasters (see, for instance, Sylves and differences, it starts with an interpretation of resi- Waugh, 1990; Institute of Civil Engineers, 1995; lience. -

Chicago, IL Convention Theme: Transgressions

ASSOCIATION FOR SLAVIC, EAST EUROPEAN, & EURASIAN STUDIES November 9-12, 2017 Chicago, IL Convention Theme: Transgressions The 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution inspires the 2017 theme and invites us to rethink the ways in which cultural, economic, political, social, and international orders are undermined, overthrown, and recast. Anna Grzymala-Busse, Stanford University ASEEES Board President 2 CONVENTION SPONSORS ASEEES thanks all of our sponsors whose generous contributions and support help to promote the continued growth and visibility of the Association during our Annual Convention and throughout the year. PLATINUM SPONSOR: Cambridge University Press; Williams College GOLD SPONSORS: Harriman Institute at Columbia U; Natasha Kozmenko Booksellers; American Councils for International Education SILVER SPONSOR: Indiana U Russian and East European Institute; Stanford U Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies; U of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Russia, East Europe, and Central Asia BRONZE SPONSORS: U of Michigan Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies; U of Texas-Austin Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies ASSOCIATE SPONSORS: New York U, Department of Russian and Slavic Studies; Ukrainian Jewish Encounter; U of Chicago, Center for East European, Russian and Eurasian Studies MOBILE APP SPONSOR: American Councils for International Education 3 Contents Convention Schedule Overview .......................................................................... 4 Program Committee for the Chicago,