SATIE Gymnopédies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yvar Mikhashoff Collection of Transcriptions - Music Library - University at Buffalo Libraries

11/21/2017 Yvar Mikhashoff Collection of Transcriptions - Music Library - University at Buffalo Libraries University at Buffalo Music Library Yvar Mikhashoff Collection of Transcriptions: Preliminary Inventory (Mus. Arc. 1.3) List prepared by Matthew J. Sheehy as part of An Annotated Catalogue of the Yvar Emilian Mikhashoff Musical Compositions and Transcriptions in the Music Library, SUNY at Buffalo: ML410.M66AXS54 1998 Indexes of titles and authors of texts available in print version. Anonymous May 23 197? Americana Seige of Tripoli Chamber Orchestra Parts: 10 parts, 12 x 9, holographs (pencil) Sketch: 21l., 12.5 x 8.5, published score (photocopies, annotations) Federal Medley Chamber Orchestra Parts: 11 parts, 12 x 9, holograph (ink) Sketch: 11l., 12 x 9, published score (photocopy, annotations) and holographs (pencil) James Sellars is credited as a transcriber on the Federal Medley.'Marked Copenhagen. Box: T 1, no. T 1 Anonymous Folk songs. Source material: 8l., 11 x 8.5, photocopies Not annotated, appears to be Sicilian folk songs. Box: T 1, no. T 2 Bach, Johann Sebastian Es ist genug Piano 1l., 10 x 7, holograph (ink), incomplete, "Fuga a 4" 2l., 12 x 9, holograph (pencil), incomplete, "Chorale-prelude based on the choral theme" Signed "MacKay" Box: T 1, no. T 3 Bach, Johann Sebastian Suite no. 4 for flute. Allegro Piano 1l., 12.5 x 9.5, holograph (pencil), file:///Y:/Music/archives/Mikhashoff/mikhashoff_transcriptions.html 1/20 11/21/2017 Yvar Mikhashoff Collection of Transcriptions - Music Library - University at Buffalo Libraries "For William Poppmann, Xmas 1971." Box: T 1, no. T 4 Bach, Johann Sebastian Well-Tempered Clavier, book 1, fugue XVI Orchestra Score: 9l., 12 x 9, holograph (pencil) Box: T 1, no. -

Keyboard Music

Prairie View A&M University HenryMusic Library 5/18/2011 KEYBOARD CD 21 The Women’s Philharmonic Angela Cheng, piano Gillian Benet, harp Jo Ann Falletta, conductor Ouverture (Fanny Mendelssohn) Piano Concerto in a minor, Op. 7 (Clara Schumann) Concertino for Harp and Orchestra (Germaine Tailleferre) D’un Soir Triste (Lili Boulanger) D’un Matin de Printemps (Boulanger) CD 23 Pictures for Piano and Percussion Duo Vivace Sonate für Marimba and Klavier (Peter Tanner) Sonatine für drei Pauken und Klavier (Alexander Tscherepnin) Duettino für Vibraphon und Klavier, Op. 82b (Berthold Hummel) The Flea Market—Twelve Little Musical Pictures for Percussion and Piano (Yvonne Desportes) Cross Corners (George Hamilton Green) The Whistler (Green) CD 25 Kaleidoscope—Music by African-American Women Helen Walker-Hill, piano Gregory Walker, violin Sonata (Irene Britton Smith) Three Pieces for Violin and Piano (Dorothy Rudd Moore) Prelude for Piano (Julia Perry) Spring Intermezzo (from Four Seasonal Sketches) (Betty Jackson King) Troubled Water (Margaret Bonds) Pulsations (Lettie Beckon Alston) Before I’d Be a Slave (Undine Smith Moore) Five Interludes (Rachel Eubanks) I. Moderato V. Larghetto Portraits in jazz (Valerie Capers) XII. Cool-Trane VII. Billie’s Song A Summer Day (Lena Johnson McLIn) Etude No. 2 (Regina Harris Baiocchi) Blues Dialogues (Dolores White) Negro Dance, Op. 25 No. 1 (Nora Douglas Holt) Fantasie Negre (Florence Price) CD 29 Riches and Rags Nancy Fierro, piano II Sonata for the Piano (Grazyna Bacewicz) Nocturne in B flat Major (Maria Agata Szymanowska) Nocturne in A flat Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 19 in C Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 8 in D Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. -

Against Expression?: Avant-Garde Aesthetics in Satie's" Parade"

Against Expression?: Avant-garde Aesthetics in Satie’s Parade A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2020 By Carissa Pitkin Cox 1705 Manchester Street Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] B.A. Whitman College, 2005 M.M. The Boston Conservatory, 2007 Committee Chair: Dr. Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract The 1918 ballet, Parade, and its music by Erik Satie is a fascinating, and historically significant example of the avant-garde, yet it has not received full attention in the field of musicology. This thesis will provide a study of Parade and the avant-garde, and specifically discuss the ways in which the avant-garde creates a dialectic between the expressiveness of the artwork and the listener’s emotional response. Because it explores the traditional boundaries of art, the avant-garde often resides outside the normal vein of aesthetic theoretical inquiry. However, expression theories can be effectively used to elucidate the aesthetics at play in Parade as well as the implications for expressability present in this avant-garde work. The expression theory of Jenefer Robinson allows for the distinction between expression and evocation (emotions evoked in the listener), and between the composer’s aesthetical goal and the listener’s reaction to an artwork. This has an ideal application in avant-garde works, because it is here that these two categories manifest themselves as so grossly disparate. -

Things Seen on Right and Left Erik Satie

image A Derain Art & Heritage Collections Jack in the Box Projet de costume pour une danseuse, 1926 Cultural Musing Cabinet 8 31 Alfred Frueh Portrait of Erik Satie Rare Books & Special Collections in collaboration with the J M Coetzee Erik Satie, Socrates Postcard, Paris 1920 Centre for Creative Practice and Art & Heritage Collections present: and John Cage Printed on card, 14 x 9 cm In the years after the First World War, Satie’s Alfred (‘Al’) Frueh (1880 – 1968) was an style moved towards what was to become known American cartoonist and caricaturist. He studied Things seen on right and left as neo-classicism. Although his reputation was in Paris from 1909 to 1924, contributing regularly based on his humorous works, Satie’s later music to the New York World, and to New Yorker from Erik Satie in words, pictures and music sometimes has a more serious character. His neo- 1925 onwards. This portrait comes from the year classical masterpiece is the ‘symphonic drama’ that Socrate was premiered. Socrate (Socrates). Following his death in 1925, Exhibition 32 Erik Satie Marche de Cocagne. Satie’s music fell into neglect until the 1950s For three trumpets in C Level 1 & 3, Barr Smith Library when there was a revival of interest in his music Reproduction of Satie’s manuscript as in the United States, particularly due to advocacy frontispiece to Almanach de Cocagne, 9 June until 24 July 2011 of the composer John Cage. Editions de la Sirène, Paris 1920 29 Erik Satie Socrate, Symphonic Drama in 223 pages, original soft cover, 11 x 16.5 cm three parts for piano and voice, composed for the Almanach de Cocagne was an annual performances of Princess Edmond de Polignac. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

Piano Works Uspud • Le Fils Des Étoiles Duanduan Hao, Piano Erik Satie (1866–1925) Erik Satie (1866–1925) Piano Works Piano Works

SATIE Piano Works Uspud • Le Fils des étoiles Duanduan Hao, Piano Erik Satie (1866–1925) Erik Satie (1866–1925) Piano Works Piano Works 1 Allegro (1884) 0:21 & Tendrement (version for piano) (1902) 3:59 While the world of music composition has attracted some borrowings and stylistic fusions. Leit-motiv du ‘Panthée’ is 2 Leit-motiv du ‘Panthée’ (1891) 0:45 Le Fils des étoiles: 3 Preludes (1891) 13:34 ‘colourful characters’, from Mozart’s vulgar letters and cat the composer’s only monodic composition, written as a 3 Verset laïque et somptueux (1900) 1:27 * Act I: Prélude, ‘La Vocation’ 4:39 impressions to Peter Warlock’s ultimately fatal interest in contribution to Joséphin Péladan’s novel Panthée (in his ( witchcraft and sadism, surely the greatest eccentric of cycle La Décadence latine: éthopée). With its unpredictable 4 Fugue-valse (1906) 1:59 Act II: Prélude, ‘L’Initiation’ 3:51 ) Act III: Prélude, ‘L’Incantation’ 4:57 them all is the Parisian, Erik Satie (1866–1925). Always harmonic shifts, Verset laïque & somptueux seems to Cinq Grimaces pour Le Songe d’une nuit d’été appearing in one of seven identical suits, Satie would eat inhabit the world of Debussy’s more reflective piano works, (arr. Darius Milhaud for piano) (1915) 3:57 Sonatine bureaucratique (1917) 4:25 ¡ only white food, carried a hammer with him to defend though the same could not be said of the relatively 5 No. 1. Préambule 0:50 I. Allegro 1:08 ™ II. Andante 1:20 himself from any assailants, and even founded his own extensive and bizarre Fugue-Valse (surely the sole attempt 6 No. -

Picasso and Music FRANZ LISZT

Picasso and music FRANZ LISZT GUITARES GITANES MANUEL DE FALLA 1 | Fandango, El Malagueño 4’08 El amor brujo (ballet) (1919-25) 9 | Canción del amor dolido. Allegro 1’30 JOAQUÍN RODRIGO (1901-1999) 10 | Danza ritual del fuego. Allegro ma non troppo e pesante 5’08 11 | Canción del fuego fatuo. Vivo 1’47 Concierto de Aranjuez (1934, orch. 1939) Marina Heredia, cantaora (9 & 11) 2 | II. Adagio 12’04 Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Pablo Heras-Casado Fantasía para un gentilhombre (1954) © Chester Music Ltd / Bureau de Musique Mario Bois BMB 3 | Españoleta 5’08 Marco Socias, guitare Orquestra de Cambra Teatre Lliure, Josep Pons IGOR STRAVINSKY Pulcinella (ballet), suite d’orchestre (1922, version révisée de 1949) © Music Schott 12 | Tarantella. Toccata 2’07 Orquestra de Cambra Teatre Lliure, Josep Pons MANUEL DE FALLA (1876-1946) © Boosey and Hawkes Ltd 4 | Canción (1900), Andante mesto 2’19 5 | Serenata andaluza (1900), Allegretto 5’30 DARIUS MILHAUD (1892-1974) Javier Perianes, piano Scaramouche (transcription pour clarinette et piano) (1937) © Manuel de Falla Ediciones 13 | I. Vif 2’58 Ronald van Spaendonck, clarinette PABLO DE SARASATE (1844-1908) Alexandre Tharaud, piano 6 | Fantaisie de concert sur des thèmes de Carmen, op. 25 (c. 1883) 13’06 © Éditions Salabert Graf Mourja, violon Natalia Gous, piano CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918) IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882-1971) 14 | Masques (1903-1904), Très vif et fantasque 4’51 Alain Planès, piano Suite no 1 pour petit orchestre (1917, orch. 1925) 7 | Española 1’08 ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) Orquestra de Cambra Teatre Lliure, Josep Pons 15 | Les pantins dansent (1929) 1’41 © Chester Music Ltd Alexandre Tharaud, piano ENRIQUE GRANADOS (1867-1916) Goyescas (1913-1915) 8 | Final del Fandango 3’19 BBC Symphony Orchestra & Singers, Josep Pons © Tritó Edicions / Albert Guinovard, revision Cette sélection musicale a été librement inspirée de l’exposition “Les Musiques de Picasso” produite par le Musée de la musique - Philharmonie de Paris en 2020. -

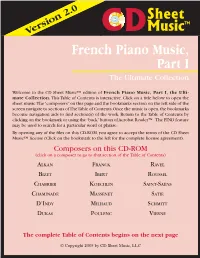

Table of Contents Is Interactive

Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 1 French Piano Music, Part I The Ultimate Collection Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ edition of French Piano Music, Part I, the Ulti- mate Collection. This Table of Contents is interactive. Click on a title below to open the sheet music. The “composers” on this page and the bookmarks section on the left side of the screen navigate to sections of The Table of Contents.Once the music is open, the bookmarks become navigation aids to find section(s) of the work. Return to the Table of Contents by clicking on the bookmark or using the “back” button of Acrobat Reader™. The FIND feature may be used to search for a particular word or phrase. By opening any of the files on this CD-ROM, you agree to accept the terms of the CD Sheet Music™ license (Click on the bookmark to the left for the complete license agreement). Composers on this CD-ROM (click on a composer to go to that section of the Table of Contents) ALKAN FRANCK RAVEL BIZET IBERT ROUSSEL CHABRIER KOECHLIN SAINT-SAËNS CHAMINADE MASSENET SATIE D’INDY MILHAUD SCHMITT DUKAS POULENC VIERNE The complete Table of Contents begins on the next page © Copyright 2005 by CD Sheet Music, LLC Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 2 VALENTIN ALKAN IV. La Bohémienne Saltarelle, Op. 23 V. Les Confidences Prélude in B Major, from 25 Préludes, VI. Le Retour Op. 31, No. 3 Variations Chromatiques de concert Symphony, from 12 Études Nocturne in D Major I. Allegro, Op. 39, No. -

Nicolas Horvath Erik Satie (1866-1925) Intégrale De La Musique Pour Piano • 3 Nouvelle Édition Salabert

comprenant DES PREMIERS ENREGISTREMENTS MONDIAUX SATIE INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT NICOLAS HORVATH ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT NICOLAS HORVATH, Piano Numéro de catalogue : GP763 Date d’enregistrement : 11 décembre 2014 Lieu d’enregistrement : Villa Bossi, Bodio, Italie Publishers: Durand/Salabert/Eschig 2016 Edition Piano : Érard de Cosima Wagner, modèle 55613, année 1881 Producteur et Éditeur : Alexis Guerbas (Les Rouages) Ingénieur du son : Ermanno De Stefani Rédaction du livret : Robert Orledge Traduction française : Nicolas Horvath Photographies de l’artiste : Laszlo Horvath Portrait du compositeur : Santiago Rusiñol Una romanza ©MNAC Couverture : Sigrid Osa L’artiste tient à remercier sincèrement Ornella Volta et la Fondation Erik Satie. 2 1 PRÉLUDE DU NAZARÉEN [EN DEUX PARTIES] ** 10:23 uspud – ballet chrétien en trois actes ** 23:53 2 Acte 1 09:33 3 Acte 2 06:20 4 Acte 3 07:53 5 EGINHARD. PRÉLUDE 02:04 6 DANSES GOTHIQUES ** 10:34 7 VEXATIONS 07:01 8 SANS TITRE, PEUT-ÊTRE POUR LA MESSE DES PAUVRES, [MODÉRÉ] 01:04 9 PRÉLUDE DE « LA PORTE HÉROÏQUE DU CIEL » ** 04:50 0 GNOSSIENNE [N° 6] 02:17 ! SANS TITRE, ?GNOSSIENNE [PETITE OUVERTURE À DANSER] ** 02:09 PIÈCES FROIDES : AIRS À FAIRE FUIR 10:00 @ D’une manière très particulière 04:30 # Modestement 01:09 $ S’inviter ** 04:19 % AIRS À FAIRE FUIR N° 2 (version plus chromatique) * 00:26 PIÈCES FROIDES : DANSES DE TRAVERS ** 06:25 ^ En y regardant à deux fois 02:02 & Passer 01:44 * Encore 02:37 ( DANSE DE TRAVERS II ** 03:12 * PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL DURÉE TOTALE: 85:03 ** PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL DE LA VERSION RÉVISÉE PAR ROBERT ORLEDGE 3 ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT À PROPOS DE NICOLAS HORVATH ET DE LA NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT DES « ŒUVRES POUR PIANO » DE SATIE. -

Pierrot Lunaire

Words and Music Liverpool Music Symposium 3 Words and Music edited by John Williamson LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2005 by LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS 4 Cambridge Street, Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © Liverpool University Press 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN 0-85323-619-4 cased Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders and the publishers will be pleased to be informed of any errors or omissions for correction in future editions. Edited and typeset by Frances Hackeson Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books, Bodmin, Cornwall Contents Notes on Contributors vii Introduction John Williamson 1 1 Mimesis, Gesture, and Parody in Musical Word-Setting Derek B. Scott 10 2 Rhetoric and Music: The Influence of a Linguistic Art Jasmin Cameron 28 3 Eminem: Difficult Dialogics David Clarke 73 4 Artistry, Expediency or Irrelevance? English Choral Translators and their Work Judith Blezzard 103 5 Pyramids, Symbols, and Butterflies: ‘Nacht’ from Pierrot Lunaire John Williamson 125 6 Music and Text in Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw Bhesham Sharma 150 7 Rethinking the Relationship Between Words and Music for the Twentieth Century: The Strange Case of Erik Satie Robert Orledge 161 vi 8 ‘Breaking up is hard to do’: Issues of Coherence and Fragmentation in post-1950 Vocal Music James Wishart 190 9 Writing for Your Supper – Creative Work and the Contexts of Popular Songwriting Mike Jones 219 Index 251 Notes on Contributors Derek Scott is Professor of Music at the University of Salford. -

THE ROCK IS STILL ROLLING FINAL.Pdf

‘THE ROCK IS STILL ROLLING’: CAMUS’ ABSURDITY AND THE MUSIC OF SATIE NIMISHI ILANGO MA by Research University of York Music December 2016 It is nigh on impossible to find examples of musicological scholarship that have correlated Western art music to the philosophical concept of absurdity as theorised by Albert Camus. Erik Satie’s music has characteristics that can be related to aspects of absurdity, despite pre- dating Camus’ theory. Much of the theory of absurdity will come from Camus’ extended essay entitled The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), which delineates his thinking on absurdity as part of the human condition: essentially that life is rendered meaningless by its unceasing, repetitive cycles. My thesis will focus on two of Satie’s works in relation to absurdity, Socrate and Vexations. Their characteristic features, such as repetition and immobility, bear a striking resemblance to the corresponding plays of the Theatre of the Absurd. The term for this category of plays and their grouping was coined by Martin Esslin, whose comparison of absurdity to another art form has been invaluable in the formulation of my own methodology. Whilst Satie may not have written in a consciously absurd way, ultimately I aim to reveal that a new and illuminating reading of Satie’s music can be generated through the lens of absurdity. LIST OF CONTENTS Abstract 2 List of Contents 3 List of Musical Examples 4 Acknowledgements 6 Declaration 7 Chapter 1: Introduction 8 Chapter 2: Absurdity 18 Chapter 3: Socrate 38 Chapter 4: Vexations 82 Chapter 5: Conclusion