Booklet-SCD1075.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Against Expression?: Avant-Garde Aesthetics in Satie's" Parade"

Against Expression?: Avant-garde Aesthetics in Satie’s Parade A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2020 By Carissa Pitkin Cox 1705 Manchester Street Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] B.A. Whitman College, 2005 M.M. The Boston Conservatory, 2007 Committee Chair: Dr. Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract The 1918 ballet, Parade, and its music by Erik Satie is a fascinating, and historically significant example of the avant-garde, yet it has not received full attention in the field of musicology. This thesis will provide a study of Parade and the avant-garde, and specifically discuss the ways in which the avant-garde creates a dialectic between the expressiveness of the artwork and the listener’s emotional response. Because it explores the traditional boundaries of art, the avant-garde often resides outside the normal vein of aesthetic theoretical inquiry. However, expression theories can be effectively used to elucidate the aesthetics at play in Parade as well as the implications for expressability present in this avant-garde work. The expression theory of Jenefer Robinson allows for the distinction between expression and evocation (emotions evoked in the listener), and between the composer’s aesthetical goal and the listener’s reaction to an artwork. This has an ideal application in avant-garde works, because it is here that these two categories manifest themselves as so grossly disparate. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

Reducing the Term of Copyright in Unpublished Works (“2039” Rule)

December 2014 Consultation on reducing the duration of copyright in unpublished (“2039”) works in accordance with section 170(2) of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 About UK Music 1. UK Music is the umbrella body representing the collective interests of the UK’s commercial music industry, from songwriters and composers to artists and musicians, studio producers, music managers, music publishers, major and independent record labels, music licensing companies and the live music sector. 2. UK Music exists to represent the UK’s commercial music sector, to drive economic growth and promote the benefits of music to British society. The members of UK Music are listed in annex 1. General 3. We see no justification to change the 2039 Rule to the extent that it impacts music, whether it is for sound recordings or musicial works. The rule constitutes a compromise achieved in 1988 in order to bring the calculation of term for unpublished works in line with the one for published works in 2039. We note that Government has not provided any evidence in the Impact Assessment which would justify their preferred Option 2a with regards to sound recordings and is otherwise very limited for other forms of works. 4. There are some important general points about the Impact Assessment that we would wish to note: a) On page 1 it is stated that the works cannot be lawfully published if copyright owners cannot be identified. The Government has recently introduced an orphan works licensing scheme to permit lawful publication of such works. In addition the Impact Assessment does not consider whether works subject to the 2039 Rule could be cleared via an extended collective licence. -

SATIE Gymnopédies

1000 YEARS OF CLASSICAL MUSIC SATIE Gymnopédies VOLUME 74 | THE MODERN ERA FAST FACTS • Erik Satie is famous for his deeply eccentric nature, which extended to his dress (at one point he bought seven identical velvet suits and then, for more than ten years, wore nothing else), his eating habits (he claimed to eat only white food: ‘eggs, sugar, shredded bones, the fat of dead animals, veal, salt, coconuts, SATIE chicken cooked in white water, mouldy fruit, rice, turnips, sausages in camphor, pastry, cheese (white Gymnopédies varieties), cotton salad, and certain kinds of fish, without their skin’), and the instructions he gave to those performing his music: his scores are full of enigmatic notes such as ‘Light as an egg’, ‘Open your head’, ERIK SATIE 1866–1925 ‘Work it out yourself’ and ‘Don’t eat too much’. Trois Gymnopédies [9’44] 1 No. 1: Lent et douloureux (Slow and full of suffering) 3’37 • His sharp wit, irreverence and refusal to do as expected led him to reject the big, lush Romantic 2 No. 2: Lent et triste (Slow and sad) 3’06 tradition of composers like Wagner, and turn instead to shorter, simpler pieces in which melody was 3 No. 3: Lent et grave (Slow and solemn) 2’54 the central element. 4 Je te veux (I Want You) 5’17 • Satie broke new ground in many different musical ways. His familiarity with the world of cabaret (he [7’16] Trois Gnossiennes supported himself for several years by working as a pianist at Le Chat Noir and other Montmartre 5 No. -

Piano Works Uspud • Le Fils Des Étoiles Duanduan Hao, Piano Erik Satie (1866–1925) Erik Satie (1866–1925) Piano Works Piano Works

SATIE Piano Works Uspud • Le Fils des étoiles Duanduan Hao, Piano Erik Satie (1866–1925) Erik Satie (1866–1925) Piano Works Piano Works 1 Allegro (1884) 0:21 & Tendrement (version for piano) (1902) 3:59 While the world of music composition has attracted some borrowings and stylistic fusions. Leit-motiv du ‘Panthée’ is 2 Leit-motiv du ‘Panthée’ (1891) 0:45 Le Fils des étoiles: 3 Preludes (1891) 13:34 ‘colourful characters’, from Mozart’s vulgar letters and cat the composer’s only monodic composition, written as a 3 Verset laïque et somptueux (1900) 1:27 * Act I: Prélude, ‘La Vocation’ 4:39 impressions to Peter Warlock’s ultimately fatal interest in contribution to Joséphin Péladan’s novel Panthée (in his ( witchcraft and sadism, surely the greatest eccentric of cycle La Décadence latine: éthopée). With its unpredictable 4 Fugue-valse (1906) 1:59 Act II: Prélude, ‘L’Initiation’ 3:51 ) Act III: Prélude, ‘L’Incantation’ 4:57 them all is the Parisian, Erik Satie (1866–1925). Always harmonic shifts, Verset laïque & somptueux seems to Cinq Grimaces pour Le Songe d’une nuit d’été appearing in one of seven identical suits, Satie would eat inhabit the world of Debussy’s more reflective piano works, (arr. Darius Milhaud for piano) (1915) 3:57 Sonatine bureaucratique (1917) 4:25 ¡ only white food, carried a hammer with him to defend though the same could not be said of the relatively 5 No. 1. Préambule 0:50 I. Allegro 1:08 ™ II. Andante 1:20 himself from any assailants, and even founded his own extensive and bizarre Fugue-Valse (surely the sole attempt 6 No. -

Erik Satie's Vexations—An Exercise in Immobility Christopher Dawson

Document généré le 23 sept. 2021 22:49 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Erik Satie's Vexations—An Exercise in Immobility Christopher Dawson Volume 21, numéro 2, 2001 Résumé de l'article La pièce pour piano Vexations d’Erik Satie comporte une « Note de l’auteur » URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014483ar où le compositeur demande apparemment aux interprètes de répéter le DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014483ar morceau 840 fois. Les opinions des biographes de Satie divergent quant à savoir si Satie voulait ou non une exécution « complète » de la pièce. Dans cet Aller au sommaire du numéro article, l’auteur évalue comment une interprétation littéraire de la Note peut jeter un éclairage sur les intentions de Satie. Il conclut que Vexations n’est pas tant un morceau de bravoure qu’un exercice : un moment musical conçu pour Éditeur(s) dégager les interprètes des notions occidentales conventionnelles de développement linéaire et de réception cumulative, en faveur d’un style Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités musical personnel d’où est absent le développement, et pour les préparer à canadiennes jouer d’autres pièces, telles une Gymnopédie ou une Gnossienne. ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Dawson, C. (2001). Erik Satie's Vexations—An Exercise in Immobility. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 21(2), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014483ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

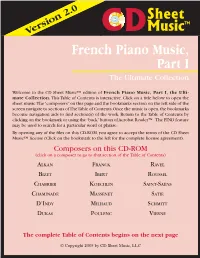

Table of Contents Is Interactive

Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 1 French Piano Music, Part I The Ultimate Collection Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ edition of French Piano Music, Part I, the Ulti- mate Collection. This Table of Contents is interactive. Click on a title below to open the sheet music. The “composers” on this page and the bookmarks section on the left side of the screen navigate to sections of The Table of Contents.Once the music is open, the bookmarks become navigation aids to find section(s) of the work. Return to the Table of Contents by clicking on the bookmark or using the “back” button of Acrobat Reader™. The FIND feature may be used to search for a particular word or phrase. By opening any of the files on this CD-ROM, you agree to accept the terms of the CD Sheet Music™ license (Click on the bookmark to the left for the complete license agreement). Composers on this CD-ROM (click on a composer to go to that section of the Table of Contents) ALKAN FRANCK RAVEL BIZET IBERT ROUSSEL CHABRIER KOECHLIN SAINT-SAËNS CHAMINADE MASSENET SATIE D’INDY MILHAUD SCHMITT DUKAS POULENC VIERNE The complete Table of Contents begins on the next page © Copyright 2005 by CD Sheet Music, LLC Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 2 VALENTIN ALKAN IV. La Bohémienne Saltarelle, Op. 23 V. Les Confidences Prélude in B Major, from 25 Préludes, VI. Le Retour Op. 31, No. 3 Variations Chromatiques de concert Symphony, from 12 Études Nocturne in D Major I. Allegro, Op. 39, No. -

Nicolas Horvath Erik Satie (1866-1925) Intégrale De La Musique Pour Piano • 3 Nouvelle Édition Salabert

comprenant DES PREMIERS ENREGISTREMENTS MONDIAUX SATIE INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT NICOLAS HORVATH ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT NICOLAS HORVATH, Piano Numéro de catalogue : GP763 Date d’enregistrement : 11 décembre 2014 Lieu d’enregistrement : Villa Bossi, Bodio, Italie Publishers: Durand/Salabert/Eschig 2016 Edition Piano : Érard de Cosima Wagner, modèle 55613, année 1881 Producteur et Éditeur : Alexis Guerbas (Les Rouages) Ingénieur du son : Ermanno De Stefani Rédaction du livret : Robert Orledge Traduction française : Nicolas Horvath Photographies de l’artiste : Laszlo Horvath Portrait du compositeur : Santiago Rusiñol Una romanza ©MNAC Couverture : Sigrid Osa L’artiste tient à remercier sincèrement Ornella Volta et la Fondation Erik Satie. 2 1 PRÉLUDE DU NAZARÉEN [EN DEUX PARTIES] ** 10:23 uspud – ballet chrétien en trois actes ** 23:53 2 Acte 1 09:33 3 Acte 2 06:20 4 Acte 3 07:53 5 EGINHARD. PRÉLUDE 02:04 6 DANSES GOTHIQUES ** 10:34 7 VEXATIONS 07:01 8 SANS TITRE, PEUT-ÊTRE POUR LA MESSE DES PAUVRES, [MODÉRÉ] 01:04 9 PRÉLUDE DE « LA PORTE HÉROÏQUE DU CIEL » ** 04:50 0 GNOSSIENNE [N° 6] 02:17 ! SANS TITRE, ?GNOSSIENNE [PETITE OUVERTURE À DANSER] ** 02:09 PIÈCES FROIDES : AIRS À FAIRE FUIR 10:00 @ D’une manière très particulière 04:30 # Modestement 01:09 $ S’inviter ** 04:19 % AIRS À FAIRE FUIR N° 2 (version plus chromatique) * 00:26 PIÈCES FROIDES : DANSES DE TRAVERS ** 06:25 ^ En y regardant à deux fois 02:02 & Passer 01:44 * Encore 02:37 ( DANSE DE TRAVERS II ** 03:12 * PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL DURÉE TOTALE: 85:03 ** PREMIER ENREGISTREMENT MONDIAL DE LA VERSION RÉVISÉE PAR ROBERT ORLEDGE 3 ERIK SATIE (1866-1925) INTÉGRALE DE LA MUSIQUE POUR PIANO • 3 NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT À PROPOS DE NICOLAS HORVATH ET DE LA NOUVELLE ÉDITION SALABERT DES « ŒUVRES POUR PIANO » DE SATIE. -

Erik Satie Bruno Fontaine Erik Satie (1866-1925)

Erik Satie Bruno Fontaine Erik Satie (1866-1925) Trois Gymnopédies Avant-dernières pensées 1. Gymnopédie no 1 3’25 22. Idylle 1’03 2. Gymnopédie no 2 2’42 23. Aubade 1’13 3. Gymnopédie no 3 2’33 24. Méditation 0’49 Enregistré les 17 et 18 juin 2015 au studio 4’33 (Ivry-sur-Seine, France) Pièces froides Nocturnes Avant toute chose, merci à Nicolas Bartholomée, pour m’avoir proposé de retrouver cet ancien compagnon- nage avec Erik Satie, une familiarité née de l’aventure théâtrale partagée avec mon cher Jean Rochefort. 25. Nocturne no 1 (Doux et calme) 3’48 Merci à l’équipe d’Aparté, Emmanuelle Gonet, Emmanuel Chollet, Ignace Hauville et Florian Bonifay, I. Airs à faire fuir 26. Nocturne no 2 (Simplement) 2’23 pour leur confiance renouvelée. 4. D’une manière très particulière 3’19 27. Nocturne no 3 Merci à Maximilien Ciup pour sa complicité artistique et attentive. 5. Modestement 1’46 (Un peu mouvementé) 3’46 Merci à Pierre Malbos, pour la superbe préparation du CFX Yamaha, et pour le plaisir que j’ai eu à enre- 6. S’inviter 3’06 28. Nocturne no 4 2’28 gistrer dans son studio 4’33. Merci à Caroline Doutre, pour la joyeuse promenade photographique à travers Montmartre. 29. Nocturne no 5 2’26 Merci à Jean-Hugues Allard pour son amitié et son soutien infaillible. II. Danse de travers Je dédie cet enregistrement, affectueusement à ma mère, Berny… 7. En y regardant à deux fois 1’44 Sept Gnossiennes Et puis, pour Françoise… de toute évidence… 8. -

SCMS Repertoire List Through 2021 Winter Festival

SEATTLE CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY REPERTOIRE LIST, 1982–2021 “FORTY YEARS OF BEAUTIFUL MUSIC” James Ehnes, Artistic Director Toby Saks (1942-2013), Founder Adams, John China Gates for Piano (2013) Arensky, Anton Hallelujah Junction for Two Pianos (2012, 2017W) Piano Quintet in D major, Op. 51 (1997, 2003, 2011W) Road Movies for Violin and Piano (2013) Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 32 (1984, 1990, 1992, 1994, 2001, 2007, 2010O, 2016W) Aho, Kalevi Piano Trio in F minor, Op. 73 (2001W, 2009) ER-OS (2018) Quartet for Violin, Viola and Two Celli in A minor, Op. 35 (1989, 1995, 2008, 2011) Albéniz, Isaac Six Piéces for Piano, Op. 53 (2013) Iberia (3 selections from) (2003) Iberia “Evocation” (2015) Arlen, Harold Wizard of Oz Fantasy (arr. William Hirtz) (2002) Alexandrov, Kristian Prayer for Trumpet and Piano (2013) Arnold, Malcolm Sonatina for Oboe and Piano, Op. 28 (2004) Applebaum "Landscape of Dreams" (1990) Babajanian, Arno Piano Trio in F sharp minor (2015) Andres, Bernard Narthex for Flute and Harp (2000W) Bach, Johann Sebastian “Aus liebe will mein Heiland sterben” from St. Matthew Passion BWV 244 Anderson, David (for flute, arr. Bennett) (2019) Capriccio No. 2 for Solo Double Bass (2006) Brandenburg Concerto No 3 in G major, BWV 1048 (2011) Four Short Pieces for Double Bass (2006) Brandenburg Concertos (Complete) BWV 1046-1051 (2013W) Capriccio “On the Departure of a Beloved Brother” in B flat major, BWV 992 Anderson, Jordan (2006) Drafts for Double Bass and Piano (2006) Chaconne, from Partita for Violin in D minor, BWV 1004 (1994, 2001, 2002) Choral Preludes for Organ (Piano) (Selections) (1998) Anonymous (arr. -

H-France Review Vol. 16 (February 2016), No. 16 Caroline Potter, Ed

H-France Review Volume 16 (2016) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 16 (February 2016), No. 16 Caroline Potter, ed., Erik Satie: Music, Art and Literature. Surrey-Burlington: Ashgate, 2013, xix + 347 pp. Notes. Musical Examples. Illustrations. £65.00. (hb). ISBN: 978-1-4094-3421-4. Compte-rendu par Michela Niccolai, Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris, Association de la Régie Théâtrale. Nous célébrons cette année l’anniversaire des quatre-vingt-dix ans de la mort d’Erik Satie (1866-1925): son humour, son mysticisme décalé et son style musical novateur ont inspiré de nombreux contemporains et, plus encore, des artistes (musiciens mais aussi plasticiens) qui lui ont succédé.[1] La silhouette de Satie est indissociable de sa production musicale: son élégant costume en velours (dont il possédait de nombreux exemplaires identiques !), le faux-col, la canne et le melon deviennent aussi célèbres que la partition des Gymnopédies. Satie lui-même a entretenu le mystère sur sa figure, ne dévoilant jamais les détails de sa vie privée, ou plutôt ne concédant jamais en avoir une. Les deux logis du compositeur--le «placard» situé 6, Cortot à Montmartre et «la chambre du crime», ainsi que l’a appelée Cocteau, au 22 de la rue Cauchy à Arcueil--sont le miroir de sa parcimonie presque obsessionnelle. Cette atmosphère sombre, poussiéreuse, contrastait évidemment avec l’image d’un compositeur mondain, comme avec la sérénité et l’ironie de ses compositions. Mais qui était Erik Satie? «Gymnopédiste» au cabaret du Chat Noir, «maître de chapelle» de l’Ordre du Temple de la Rose+Croix, élève dans la classe de contrepoint à la Schola cantorum, «précurseur» de la nouvelle génération de compositeurs guidée par Maurice Ravel… tant de facettes différentes pour une personnalité hors du commun.