Sample Thesis Proposal: Melanie James ('12)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Article Fairy Marriages in Tolkien’S Works GIOVANNI C

article Fairy marriages in Tolkien’s works GIOVANNI C. COSTABILE Both in its Celtic and non-Celtic declinations, the motif the daughter of the King of Faerie, who bestows on him a of the fairy mistress has an ancient tradition stretching magical source of wealth, and will visit him whenever he throughout different areas, ages, genres, media and cul- wants, so long as he never tells anybody about her.5 Going tures. Tolkien was always fascinated by the motif, and used further back, the nymph Calypso, who keeps Odysseus on it throughout his works, conceiving the romances of Beren her island Ogygia on an attempt to make him her immortal and Lúthien, and Aragorn and Arwen. In this article I wish husband,6 can be taken as a further (and older) version of to point out some minor expressions of the same motif in the same motif. Tolkien’s major works, as well as to reflect on some over- But more pertinent is the idea of someone’s ancestor being looked aspects in the stories of those couples, in the light of considered as having married a fairy. Here we can turn to the often neglected influence of Celtic and romance cultures the legend of Sir Gawain, as Jessie Weston and John R. Hul- on Tolkien. The reader should also be aware that I am going bert interpret Gawain’s story in Sir Gawain and the Green to reference much outdated scholarship, that being my pre- Knight as a late, Christianised version of what once was a cise intent, though, at least since this sort of background fairy-mistress tale in which the hero had to prove his worth may conveniently help us in better understanding Tolkien’s through the undertaking of the Beheading Test in order to reading of both his theoretical and actual sources. -

Was Gawain a Gamer? Gus Forester East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 12-2014 Was Gawain a Gamer? Gus Forester East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Forester, Gus, "Was Gawain a Gamer?" (2014). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 249. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/249 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Forester 1 Department of Literature and Language East Tennessee State University Was Gawain a Gamer? Gus Forester An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the English Honors-in-Discipline Program _________________________________________ Dr. Thomas Crofts, Thesis Director 12/4/2014 _________________________________________ Dr. Mark Holland, Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dr. Leslie MacAvoy, Faculty Advisor Forester 2 Introduction The experience of playing a game can be summarized with three key elements. The first element is the actions performed by the player. The second element is the player’s hope that precedes his actions, that is to say the player’s belief that such actions are possible within the game world. The third and most interesting element is that which precedes the player’s hope: the player’s encounter with the superplayer. This encounter can come in either the metaphorical sense of the player’s discovering what is possible as he plots his actions or in the literal sense of watching someone show that it is possible, but it must, by definition, be a memorable experience. -

Distressing Damsels: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight As a Loathly Lady Tale

Distressing Damsels: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight as a Loathly Lady Tale By Lauren Chochinov A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2010 by Lauren Chochinov i Abstract At the end of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, when Bertilak de Hautdesert reveals Morgan le Fay’s involvement in Gawain’s quest, the Pearl Poet introduces a difficult problem for scholars and students of the text. Morgan appears out of nowhere, and it is difficult to understand the poet’s intentions for including her so late in his narrative. The premise for this thesis is that the loathly lady motif helps explain Morgan’s appearance and Gawain’s symbolic importance in the poem. Through a study of the loathly lady motif, I argue it is possible that the Pearl Poet was using certain aspects of the motif to inform his story. Chapter one of this thesis will focus on the origins of the loathly lady motif and the literary origins of Morgan le Fay. In order to understand the connotations of the loathly lady stories, it is important to study both the Irish tales and the later English versions of the motif. My study of Morgan will trace her beginnings as a pagan healer goddess to her later variations in French and Middle English literature. The second chapter will discuss the influential women in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and their specific importance to the text. -

An Analysis of Sexual Agency and Seduction in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Advised by Dr. Theodore Leinbaugh The Performativity of Temptation: An Analysis of Sexual Agency and Seduction in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight By Jordan Lynn Stinnett Honors Thesis Department of English and Comparative Literature University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill 2018 Approved: __________________________________________ Abstract In my analysis of the medieval romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, I focus on the paradoxical representation of female sexuality exhibited in the temptation scenes. I argue that Lady Bertilak’s sexuality is a unique synthesis of Christian and Celtic archetypes whose very construction lends her the ability to rearticulate her own sexual agency. It is only by reconciling these two theological frameworks that we can understand how she is duly empowered and disempowered by her own seduction of Gawain. Through the Christian “Eve-as-temptress” motif, the Lady’s feminine desire is cast as duplicitous and threatening to the morality of man. However, her embodiment of the Celtic sovereignty-goddess motif leads to the reclamation of her sexual power. Ultimately, the temptation scenes provide the Lady with the literary space necessary to redefine her feminine agency and reconstruct the binary paradigms of masculinity and femininity. II TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………….1 CHAPTER ONE: THE GENESIS OF TEMPTATION…………………...……………………6 CHAPTER TWO: THE SOVEREIGNTY OF TEMPTATION……………………………….23 CONCLUSION THE PERFORMATIVITY OF TEMPTATION……………..…………….38 WORKS CITED…………………………………………………………………..42 III 4 INTRODUCTION Operating under the guise of temptation, gender relations and sexual power drive the plot of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Guided by Morgan le Fay’s plans to test his honor, Lady Bertilak seduces Gawain in a series of episodes commonly referred to as the “temptation scenes”. -

Women and Magic in Medieval Literature

Women and Magic in Medieval Literature by Jessica Leigh In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in The Department of English State University of New York New Paltz, New York 12561 November 2019 WOMEN AND MAGIC IN MEDIEVAL LITERATURE Jessica Leigh State University of New York at New Paltz _______________________________________ We, the thesis committee for the above candidate for the Master of Arts degree, hereby recommend Acceptance of this thesis. _______________________________________ Daniel Kempton, Thesis Advisor Department of English, SUNY New Paltz _______________________________________ Cyrus Mulready, Thesis Committee Member Department of English, SUNY New Paltz Approved on 12/06/2019 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Master of Arts degree in English at the State University of New York at New Paltz Leigh 1 One of the defining features of medieval literature is its relationship with a particular tradition of magic. Arthurian chivalric romance stands among some of the most well-known and enduring medieval literary pieces, appearing as a staple of Renaissance medievalism, Victorian medievalism, the work of pre-Raphaelites, and in modern pop culture, as in programs like Merlin. The tropes of Arthurian chivalric romance remain major identifiers of the Middle Ages. Even other major medieval texts still largely known and commonly studied in schools and universities today incorporate elements of the Arthurian tradition, as in The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, or the wider chivalric tradition, as in the lais of Marie de France. The fictional worlds encompassed by medieval literature contain many legendary creatures, prophesied events, and magical items which give color and memorable character to these many tales. -

Medieval Mirroring: Fantastic Space and the Qualities That Native Characters Reflect

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2018 Medieval Mirroring: Fantastic Space and the Qualities that Native Characters Reflect Donald Jacob Baggett University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Recommended Citation Baggett, Donald Jacob, "Medieval Mirroring: Fantastic Space and the Qualities that Native Characters Reflect. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2018. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/5172 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Donald Jacob Baggett entitled "Medieval Mirroring: Fantastic Space and the Qualities that Native Characters Reflect." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Laura L. Howes, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary C. Dzon, Heather A. Hirschfeld Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Medieval Mirroring: Fantastic Space and the Qualities that Native Characters Reflect A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Donald Jacob Baggett August 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Donald Jacob Baggett All rights reserved. -

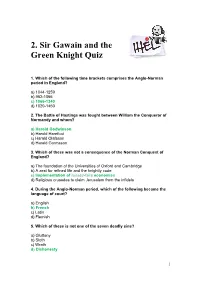

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Quiz

2. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Quiz 1. Which of the following time brackets comprises the Anglo-Norman period in England? a) 1044-1259 b) 952-1066 c) 1066-1340 d) 1020-1450 2. The Battle of Hastings was fought between William the Conqueror of Normandy and whom? a) Harold Godwinson b) Harold Harefoot c) Harald Olafsson d) Harald Gormsson 3. Which of these was not a consequence of the Norman Conquest of England? a) The foundation of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge b) A zest for refined life and the knightly code c) Implementation of laissez-faire economics d) Religious crusades to claim Jerusalem from the infidels 4. During the Anglo-Norman period, which of the following became the language of court? a) English b) French c) Latin d) Flemish 5. Which of these is not one of the seven deadly sins? a) Gluttony b) Sloth c) Wrath d) Dishonesty 1 6. The “Wheel of Fortune” was a pervasive idea throughout the Middle Ages. What did it not represent? a) The ephemeral nature of earthly things b) The stability of all things c) An evolution of the Old English “wyrd” d) That important things in life come from within 7. The Ptolemaic conception of the universe stated what? a) That the earth was located at the centre of the universe b) That the sun was located at the centre of the universe c) That the planets align once every decade d) That the Age of Aquarius would signify the end of the world 8. How many estates was medieval society divided into? a) 2 b) 3 c) 4 d) 5 9. -

Masarykova Univerzita Portrayal of Women in Arthurian Legends

Masarykova univerzita Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Portrayal of women in Arthurian legends Bachelor thesis Brno, 2012 Supervisor: Author: Mgr. Jarolslav Izavčuk Petr Crhonek 1 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou bakalářskou vypracoval samostatně, s využitím pouze citovaných literárních pramenů, dalších informací a zdrojů v souladu s disciplinárním řádem pro studenty Pedagogické fakulty Masarykovy univerzity a se zákonem č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů (autorský zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů. Souhlasím, aby tato práce byla použitá jako zdroj studijních materiálů. Blansko, 23.září 2012 Petr Crhonek ……………………………………… 2 Annotation This bachelor thesis is aimed at women characters that can be met when reading Sir Thomas Malory’s L’Morte d’Arthur and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight from an unknown author. The thesis is to describe the characters, analyse them and compare to real women that were important throughout the history. In the end of this thesis there are interviews that were carried out by the author during his stay in England in the town of Barnstaple, Devon and pictures taken by the author that are to show some famous and interesting places connected to the legends of King Arthur. Key words King Arthur, women in Arthurian legends, Different roles of women, social status of women, women’s activities, crisis of masculinity, women as warriors, women as ladies-in-waiting, Morte d’Arthur, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. 3 Acknowledgement I would like to thank to Mgr. Jaroslav Izavčuk for supervising this thesis and his useful guidance. -

Ben Mccabe. Gawain Thesis

Ben McCabe Sir Gawain and Scholasticism Department of English The University of Sydney !2 Introduction Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is perhaps today the best-known and widely-read Middle English romance, even if it is most often known and read in modern translation. The appeal of the poem lies in the anonymous poet’s skill in creating the poem’s Romance world, that mixes magical effect with the performance of the chivalric ideal, and the playful laxity of courteous morality with the earnestness of the Christian ethic. The conventions of the Arthurian tradition and characterizations are recast with disarming originality, drawing the reader into the texts complexities in a way that can be compared to the confused perceptions of Gawain himself. The richness SGGK1 offers modern readers many ways into the poem’s ideas, but I will argue in this thesis that the thought-world in which the poet lived should not be left behind in modern approaches to the romance. My focus will be on a central question of the poem—the problem of facing death—contextualized in a discussion of medieval ways of thinking about the ethical dilemmas that the poem creates for its central character, Sir Gawain. In the following thesis, I will offer a reading of the Middle English romance of SGGK2 that contextualises the poem within the framework of Scholastic thought, focusing in particular on the influence of the Scholastic discussions of moral philosophy, in order to better understand the poem’s treatment of moral indeterminacy. In the opening preface I outline my reasons for adopting this approach, while also acknowledging that such a methodology is not entirely new in the scholarship surrounding SGGK. -

Some Tales That Inform Ecolore and Ecospheric Living

Australian Folklore 32, 2017 37 Further Elements of Ecolore: Some Tales that Inform Ecolore and Ecospheric Living Julie Hawkins1 ABSTRACT: This essay delves further into two groups of mediaeval literary figures from Arthurian works, both of which were featured in a previous article on Ecolore. Both reflect upon a type of contract or bond that exists between humans and representatives of Nature and is evoked during participation in the sacred, as it is implicit in the rites of magic and worship. Texts to be discussed include Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and some sections from works that involve Merlin, written by Nennius, Geoffrey of Monmouth, and Robert de Boron. Finally, the presence of values and ethics encountered in such ancient lore is considered, with some evaluation of potential implications for our study of Ecolore. KEYWORDS: Ecolore; Mythology; Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; Geoffrey of Monmouth; Merlin Introduction Since ancient times, contracts and agreements have existed between humankind and the natural world, and were once understood implicitly as part of life. They were included in traditional culture in the forms of prayers, poetry, dance, drama, invocation and ritual, all elements involved in sacred ceremony and performance. Although largely set aside in recent times in order to facilitate modern industrial methods of production, such agreements do still exist. They are evident in the ethical systems inherited from ancient European ancestors, and are able, at any time, to be clearly stated by the world's First Nations populations. Many individuals are remembering aspects of these agreements as they explore their personal relationships with animals and the environment, but a majority of the world's business operations have thus far scarcely acknowledged their existence. -

Title of Paper

International Conference on Social Science, Education Management and Sports Education (SSEMSE 2015) Journey of Test and Self-discovery ----Chivalric Virtues and Human Nature in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Qian Wu North China Institute of Science and Technology, Hebei, China ABSTRACT: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a fourteen-century poem and generally regarded as the best poem of the Medieval Arthurian literature, featuring its beautiful language, breathtaking plots and subtle and refined characterization. It tells the story of Sir Gawain, one of the best King Arthur’s knights who answers the Green Knight’s beheading challenge and stands tests from the latter. This paper will interpret Gawain’s adventure as a journey of test as well as a journey of self-discovery by textual analysis and elaborate the humanism as well as chivalric virtues the poem reflects. KEYWORD: Chivalric virtues; Human nature; Test; Self-discovery 1 INTRODUCTION the Green Knight’s head. The supernatural Green Knight picks up his head and leaves, claiming his Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a fourteen- challenge again. In the second part, Gawain sets off century poem, which tells the story of Sir Gawain, to search for the Green Chapel as he has promised. one of the best King Arthur’s knights, who answers His determination never falters despite of harsh the Green Knight’s beheading challenge and stands natural environment and the solitude in the the test from the latter. The poem is generally adventure. In the woods, he is warmly welcomed by regarded as the best poem of the Medieval Arthurian Lord Bertilak in his castle and agrees to stay till the literature, featuring its beautiful language, upcoming New Year since he is told the Green breathtaking plots and subtle and refined Chapel is nearby. -

Feminine Quests in Arthurian Legends

Spangler, E., March 2015 www.sparksjournal.org/feminine-quests Feminine Quests in Arthurian Legends Emily Spangler, Department of English and Modern Languages, Shepherd University This paper examines the correlation between women, purpose, and power within the medieval Arthurian legends. Women had little to no power during the Middle Ages, and the patriarchal ideology that dominated the culture is reflected in literature. However, my essay shows that even though women play supporting roles in Arthurian legends, they often propel the plotline to heroism and adventure. Often nameless, they barely get credit for their characterization, but my analysis of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, a chivalric romance, and “Lanval,” one of Marie de France’s lais, illustrates how the tales’ women characters wield more power than one would expect. Lady Bertilak controls Gawain through tokens and guilt, while the fairy woman from “Lanval” becomes a heroine in her own right by “saving” Lanval from Arthur’s court. Through close textual analysis and extensive research from scholars who specialize in medieval literature, I show how powerful women can be found in Arthurian legends. Medieval literature tends to center words, what will the women gain if they around men, because men were the primary acquire these men as lovers? Three possible rulers, land owners, and knights. In most of reasons that resonate in both pieces, but in the tales that capture the stories of King different contexts, are love, reputation, and Arthur’s court, the women who influence the power. Courtly love is a significant and plotline remain nameless, thus perpetuating relevant occurrence in Arthurian legends, their limited role in a patriarchal society.