Some Tales That Inform Ecolore and Ecospheric Living

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Article Fairy Marriages in Tolkien’S Works GIOVANNI C

article Fairy marriages in Tolkien’s works GIOVANNI C. COSTABILE Both in its Celtic and non-Celtic declinations, the motif the daughter of the King of Faerie, who bestows on him a of the fairy mistress has an ancient tradition stretching magical source of wealth, and will visit him whenever he throughout different areas, ages, genres, media and cul- wants, so long as he never tells anybody about her.5 Going tures. Tolkien was always fascinated by the motif, and used further back, the nymph Calypso, who keeps Odysseus on it throughout his works, conceiving the romances of Beren her island Ogygia on an attempt to make him her immortal and Lúthien, and Aragorn and Arwen. In this article I wish husband,6 can be taken as a further (and older) version of to point out some minor expressions of the same motif in the same motif. Tolkien’s major works, as well as to reflect on some over- But more pertinent is the idea of someone’s ancestor being looked aspects in the stories of those couples, in the light of considered as having married a fairy. Here we can turn to the often neglected influence of Celtic and romance cultures the legend of Sir Gawain, as Jessie Weston and John R. Hul- on Tolkien. The reader should also be aware that I am going bert interpret Gawain’s story in Sir Gawain and the Green to reference much outdated scholarship, that being my pre- Knight as a late, Christianised version of what once was a cise intent, though, at least since this sort of background fairy-mistress tale in which the hero had to prove his worth may conveniently help us in better understanding Tolkien’s through the undertaking of the Beheading Test in order to reading of both his theoretical and actual sources. -

A New Fantasy of Crusade : Sarras in the Vulgate Cycle. Christopher Michael Herde University of Louisville

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2019 A new fantasy of crusade : Sarras in the vulgate cycle. Christopher Michael Herde University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Herde, Christopher Michael, "A new fantasy of crusade : Sarras in the vulgate cycle." (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3226. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3226 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NEW FANTASY OF CRUSADE: SARRAS IN THE VULGATE CYCLE By Christopher Michael Herde B.A., University of Louisville, 2016 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2019 Copyright 2019 by Christopher Michael Herde All Rights Reserved A NEW FANTASY OF CRUSADE: SARRAS IN THE VUGLATE CYCLE By Christopher Michael Herde B.A., University of -

Was Gawain a Gamer? Gus Forester East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 12-2014 Was Gawain a Gamer? Gus Forester East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Forester, Gus, "Was Gawain a Gamer?" (2014). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 249. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/249 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Forester 1 Department of Literature and Language East Tennessee State University Was Gawain a Gamer? Gus Forester An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the English Honors-in-Discipline Program _________________________________________ Dr. Thomas Crofts, Thesis Director 12/4/2014 _________________________________________ Dr. Mark Holland, Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dr. Leslie MacAvoy, Faculty Advisor Forester 2 Introduction The experience of playing a game can be summarized with three key elements. The first element is the actions performed by the player. The second element is the player’s hope that precedes his actions, that is to say the player’s belief that such actions are possible within the game world. The third and most interesting element is that which precedes the player’s hope: the player’s encounter with the superplayer. This encounter can come in either the metaphorical sense of the player’s discovering what is possible as he plots his actions or in the literal sense of watching someone show that it is possible, but it must, by definition, be a memorable experience. -

Distressing Damsels: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight As a Loathly Lady Tale

Distressing Damsels: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight as a Loathly Lady Tale By Lauren Chochinov A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2010 by Lauren Chochinov i Abstract At the end of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, when Bertilak de Hautdesert reveals Morgan le Fay’s involvement in Gawain’s quest, the Pearl Poet introduces a difficult problem for scholars and students of the text. Morgan appears out of nowhere, and it is difficult to understand the poet’s intentions for including her so late in his narrative. The premise for this thesis is that the loathly lady motif helps explain Morgan’s appearance and Gawain’s symbolic importance in the poem. Through a study of the loathly lady motif, I argue it is possible that the Pearl Poet was using certain aspects of the motif to inform his story. Chapter one of this thesis will focus on the origins of the loathly lady motif and the literary origins of Morgan le Fay. In order to understand the connotations of the loathly lady stories, it is important to study both the Irish tales and the later English versions of the motif. My study of Morgan will trace her beginnings as a pagan healer goddess to her later variations in French and Middle English literature. The second chapter will discuss the influential women in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and their specific importance to the text. -

The Theme of the Magical Weapon 1. Excalibur

The Theme of the Magical Weapon Below, you will find three stories or portions of stories from different myths, movies, and legends. All three are tales about a magical sword or a wand. They all have similarities and differences. Focus on the similarities. Use the chart below to compare these items to one another. 1. Excalibur Excalibur is the mythical sword of King Arthur, sometimes attributed with magical powers or associated with the rightful sovereignty of Great Britain. Sometimes Excalibur and the Sword in the Stone (the proof of Arthur's lineage) are said to be the same weapon, but in most versions they are considered separate. The sword was associated with the Arthurian legend very early; in Welsh, the sword was called Caledfwlch. Excalibur and the Sword in the Stone In surviving accounts of Arthur, there are two originally separate legends about the sword's origin. The first is the "Sword in the Stone" legend, originally appearing in Robert de Boron's poem Merlin, in which Excalibur can only be drawn from the stone by Arthur, the rightful king. The second comes from the later Post-Vulgate Suite du Merlin, which was taken up by Sir Thomas Malory. Here, Arthur receives Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake after breaking his first sword, called Caliburn, in a fight with King Pellinore. The Lady of the Lake calls the sword "Excalibur, that is as to say as Cut-steel," and Arthur takes it from a hand rising out of the lake. As Arthur lay dying, he tells a reluctant Sir Bedivere (Sir Griflet in some versions) to return the sword to the lake by throwing it into the water. -

An Analysis of Sexual Agency and Seduction in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Advised by Dr. Theodore Leinbaugh The Performativity of Temptation: An Analysis of Sexual Agency and Seduction in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight By Jordan Lynn Stinnett Honors Thesis Department of English and Comparative Literature University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill 2018 Approved: __________________________________________ Abstract In my analysis of the medieval romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, I focus on the paradoxical representation of female sexuality exhibited in the temptation scenes. I argue that Lady Bertilak’s sexuality is a unique synthesis of Christian and Celtic archetypes whose very construction lends her the ability to rearticulate her own sexual agency. It is only by reconciling these two theological frameworks that we can understand how she is duly empowered and disempowered by her own seduction of Gawain. Through the Christian “Eve-as-temptress” motif, the Lady’s feminine desire is cast as duplicitous and threatening to the morality of man. However, her embodiment of the Celtic sovereignty-goddess motif leads to the reclamation of her sexual power. Ultimately, the temptation scenes provide the Lady with the literary space necessary to redefine her feminine agency and reconstruct the binary paradigms of masculinity and femininity. II TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………….1 CHAPTER ONE: THE GENESIS OF TEMPTATION…………………...……………………6 CHAPTER TWO: THE SOVEREIGNTY OF TEMPTATION……………………………….23 CONCLUSION THE PERFORMATIVITY OF TEMPTATION……………..…………….38 WORKS CITED…………………………………………………………………..42 III 4 INTRODUCTION Operating under the guise of temptation, gender relations and sexual power drive the plot of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Guided by Morgan le Fay’s plans to test his honor, Lady Bertilak seduces Gawain in a series of episodes commonly referred to as the “temptation scenes”. -

Women and Magic in Medieval Literature

Women and Magic in Medieval Literature by Jessica Leigh In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in The Department of English State University of New York New Paltz, New York 12561 November 2019 WOMEN AND MAGIC IN MEDIEVAL LITERATURE Jessica Leigh State University of New York at New Paltz _______________________________________ We, the thesis committee for the above candidate for the Master of Arts degree, hereby recommend Acceptance of this thesis. _______________________________________ Daniel Kempton, Thesis Advisor Department of English, SUNY New Paltz _______________________________________ Cyrus Mulready, Thesis Committee Member Department of English, SUNY New Paltz Approved on 12/06/2019 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Master of Arts degree in English at the State University of New York at New Paltz Leigh 1 One of the defining features of medieval literature is its relationship with a particular tradition of magic. Arthurian chivalric romance stands among some of the most well-known and enduring medieval literary pieces, appearing as a staple of Renaissance medievalism, Victorian medievalism, the work of pre-Raphaelites, and in modern pop culture, as in programs like Merlin. The tropes of Arthurian chivalric romance remain major identifiers of the Middle Ages. Even other major medieval texts still largely known and commonly studied in schools and universities today incorporate elements of the Arthurian tradition, as in The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, or the wider chivalric tradition, as in the lais of Marie de France. The fictional worlds encompassed by medieval literature contain many legendary creatures, prophesied events, and magical items which give color and memorable character to these many tales. -

The Symbolism of the Holy Grail

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 1962 The symbolism of the Holy Grail : a comparative analysis of the Grail in Perceval ou Le Conte del Graal by Chretien de Troyes and Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach Karin Elizabeth Nordenhaug Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Nordenhaug, Karin Elizabeth, "The symbolism of the Holy Grail : a comparative analysis of the Grail in Perceval ou Le Conte del Graal by Chretien de Troyes and Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach" (1962). Honors Theses. 1077. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1077 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND LIBRARIES ~lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll3 3082 01028 5079 r THE SYMBOLISM OF THE HOLY GRAIL A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GRAIL In PERCEVAL ou LE CONTE del GRAAL by CHRETIEN de TROYES and PARZIVAL by WOLFRAM von ESCHENBACH by Karin Elizabeth Nordenhaug A Thesis prepared for Professor Wright In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Honors Program And in candidacy for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Westhampton College University of Richmond, Va. May 1962 P R E F A C E If I may venture to make a bold comparison, I have often felt like Sir Perceval while writing this thesis. Like. him, I set out on a quest for the Holy Grail. -

Medieval Mirroring: Fantastic Space and the Qualities That Native Characters Reflect

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2018 Medieval Mirroring: Fantastic Space and the Qualities that Native Characters Reflect Donald Jacob Baggett University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Recommended Citation Baggett, Donald Jacob, "Medieval Mirroring: Fantastic Space and the Qualities that Native Characters Reflect. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2018. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/5172 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Donald Jacob Baggett entitled "Medieval Mirroring: Fantastic Space and the Qualities that Native Characters Reflect." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Laura L. Howes, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary C. Dzon, Heather A. Hirschfeld Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Medieval Mirroring: Fantastic Space and the Qualities that Native Characters Reflect A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Donald Jacob Baggett August 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Donald Jacob Baggett All rights reserved. -

Britanniae (12Th-15Th C.)

Royal adultery and illegitimacy: moral and political issues raised by the story of Utherpandragon and Ygerne in the French rewritings of the Historia Regum Britanniae (12th-15th c.) Irène Fabry-Tehranchi British Library In the widely spread Historia Regum Britanniae by Geoffrey of Monmouth (1138),1 which survives in about 200 manuscripts, Merlin's magic helps King Utherpandragon to fulfill his love for the duchess of Tintagel, by giving him the duke's appearance. Ygerne is deceived, but this union eventually leads to the conception of Arthur. The episode has been discussed in relation with its sources: according to E. Faral, the story could be inspired by the love of Jupiter, who with the help of Mercury takes the shape of Amphitryon to deceive his wife Alcmene, who gives birth to Hercules.2 For L. Mathey-Maille, the story of the conception of Arthur could come from a legendary or folkloric source from Celtic origins with a later moralising addition of a biblical reference.3 The passage has also been analysed through mythical structures like the three Dumezilian indo-european functions which involve fertility, war and religion. J. Grisward has shown that in order to lie with Ygerne, Uther successively offers her gold and jewelry, engages in military conflict, and eventually resorts to magic.4 Politically, because of Merlin's essential participation and privileged connection with the supernatural, Uther cannot assume alone a full sovereignty, but he needs Merlin's assistance.5 The change brought by the author of the prose Merlin to the story of Arthur's conception makes it fit even better with the myth of the hero's birth examined by O. -

FLLG 440.02: the Grail Quest - Studies in Comparative Literature Paul A

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Fall 9-1-2003 FLLG 440.02: The Grail Quest - Studies in Comparative Literature Paul A. Dietrich University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Recommended Citation Dietrich, Paul A., "FLLG 440.02: The Grail Quest - Studies in Comparative Literature" (2003). Syllabi. 9549. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/9549 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Grail Quest Studies in Comparative Literature (LS 455.02/ FLLG 440.02/ ENLT 430.02) Paul A Dietrich Fall,2003 Office: LA 101 A TR 2:10-3:30 Phone: x2805 LA303 (paul. dietrich@mso. umt. edu) 3 credits Hours: MWF 10-11 & by appointment An introduction to the major medieval English, French, Welsh and German romances ofthe grail. One group focuses on the hero/ knight/ fool who undertakes the quest, e.g., Chretien ofTroyes' Perceval, the Welsh Peredur, the French Perlesvaus, and Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival. A second group emphasizes the object ofthe quest, the grail and other talismans, and contextualizes the quest within universal history, or the wider Arthurian world; e.g., Robert de Boron's Joseph ofArimathea, The Quest ofthe Holy Grail, and Malory's Le Mo rte D 'Arthur. -

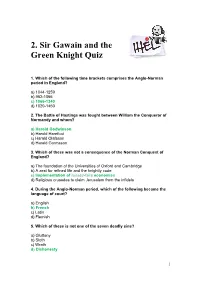

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Quiz

2. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Quiz 1. Which of the following time brackets comprises the Anglo-Norman period in England? a) 1044-1259 b) 952-1066 c) 1066-1340 d) 1020-1450 2. The Battle of Hastings was fought between William the Conqueror of Normandy and whom? a) Harold Godwinson b) Harold Harefoot c) Harald Olafsson d) Harald Gormsson 3. Which of these was not a consequence of the Norman Conquest of England? a) The foundation of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge b) A zest for refined life and the knightly code c) Implementation of laissez-faire economics d) Religious crusades to claim Jerusalem from the infidels 4. During the Anglo-Norman period, which of the following became the language of court? a) English b) French c) Latin d) Flemish 5. Which of these is not one of the seven deadly sins? a) Gluttony b) Sloth c) Wrath d) Dishonesty 1 6. The “Wheel of Fortune” was a pervasive idea throughout the Middle Ages. What did it not represent? a) The ephemeral nature of earthly things b) The stability of all things c) An evolution of the Old English “wyrd” d) That important things in life come from within 7. The Ptolemaic conception of the universe stated what? a) That the earth was located at the centre of the universe b) That the sun was located at the centre of the universe c) That the planets align once every decade d) That the Age of Aquarius would signify the end of the world 8. How many estates was medieval society divided into? a) 2 b) 3 c) 4 d) 5 9.