King Arthur's "Draconarius" Author(S): LINDA A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 6-10-2019 The Creation of a King: How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur Marcos Morales II [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Cultural History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Morales II, Marcos, "The Creation of a King: How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur" (2019). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 276. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/276 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. The Creation of a King: How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur. By: Marcos Morales II Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor David Doellinger Western Oregon University June 05, 2019 Readers Professor Elizabeth Swedo Professor Bau Hwa Hsieh Copyright © Marcos Morales II Arthur, with a single division in which he had posted six thousand, six hundred, and sixty-six men, charged at the squadron where he knew Mordred was. They hacked a way through with their swords and Arthur continued to advance, inflicting terrible slaughter as he went. It was at this point that the accursed traitor was killed and many thousands of his men with him.1 With the inclusion of this feat between King Arthur and his enemies, Geoffrey of Monmouth shows Arthur as a mighty warrior, one who stops at nothing to defeat his foes. -

A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz's Spanish Suite Op

A COMPARISON OF THE PIANO AND GUITAR VERSIONS OF ISAAC ALBÉNIZ'S SPANISH SUITE OP. 47 by YI-YIN CHIEN A LECTURE-DOCUMENT Presented to the School of Music and Dance of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts November 2016 2 “A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz’s Spanish Suite, Op. 47’’ a document prepared by Yi-Yin Chien in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance. This document has been approved and accepted by: Jack Boss, Chair of the Examining Committee Date: November 20th, 2016 Committee in Charge: Dr. Jack Boss, Chair Dr. Juan Eduardo Wolf Dr. Dean Kramer Accepted by: Director of Graduate Studies, School of Music and Dance © 2016 Yi-Yin Chien 3 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Yi-Yin Chien PLACE OF BIRTH: Taiwan DATE OF BIRTH: November 02, 1986 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Tainan National University of Arts DEGREES AWARDED: Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016, University of Oregon Master of Music, 2011, Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Bachelor of Music, 2009, Tainan National University of Arts AREAS OF SPECIAL INTEREST: Piano Pedagogy Music Theory PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: College Piano Teaching, University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance, 09/2014 - 06/2015 Taught piano lessons for music major and non-major college students Graduate Teaching -

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight As a Loathly Lady Tale by Lauren Chochinov a Thesis Submitted to the Facult

Distressing Damsels: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight as a Loathly Lady Tale By Lauren Chochinov A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2010 by Lauren Chochinov Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70110-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70110-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Nennius' Historia Brittonum

Nennius’ ‘Historia Brittonum’ Translated by Rev. W. Gunn & J. A. Giles For convenience, this text has been assembled and composed into this PDF document by Camelot On-line. Please visit us on-line at: http://www.heroofcamelot.com/ The Historia Brittonum Table of Contents Acknowledgements....................................................................................................................................4 Preface........................................................................................................................................................5 I. THE PROLOGUE..................................................................................................................................6 1.............................................................................................................................................................6 2.............................................................................................................................................................7 II. THE APOLOGY OF NENNIUS...........................................................................................................7 3.............................................................................................................................................................7 III. THE HISTORY ...................................................................................................................................8 4,5..........................................................................................................................................................8 -

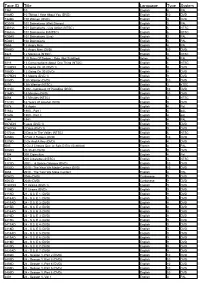

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

A New Fantasy of Crusade : Sarras in the Vulgate Cycle. Christopher Michael Herde University of Louisville

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2019 A new fantasy of crusade : Sarras in the vulgate cycle. Christopher Michael Herde University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Herde, Christopher Michael, "A new fantasy of crusade : Sarras in the vulgate cycle." (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3226. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3226 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NEW FANTASY OF CRUSADE: SARRAS IN THE VULGATE CYCLE By Christopher Michael Herde B.A., University of Louisville, 2016 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2019 Copyright 2019 by Christopher Michael Herde All Rights Reserved A NEW FANTASY OF CRUSADE: SARRAS IN THE VUGLATE CYCLE By Christopher Michael Herde B.A., University of -

Introduction: the Legend of King Arthur

Department of History University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire “HIC FACET ARTHURUS, REX QUONDAM, REXQUE FUTURUS” THE ANALYSIS OF ORIGINAL MEDIEVAL SOURCES IN THE SEARCH FOR THE HISTORICAL KING ARTHUR Final Paper History 489: Research Seminar Professor Thomas Miller Cooperating Professor: Professor Matthew Waters By Erin Pevan November 21, 2006 1 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire with the consent of the author. 2 Department of History University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Abstract of: “HIC FACET ARTHURUS, REX QUONDAM, REXQUE FUTURUS” THE ANALYSIS OF ORIGINAL MEDIEVAL SOURCES IN THE SEARCH FOR THE HISTORICAL KING ARTHUR Final Paper History 489: Research Seminar Professor Thomas Miller Cooperating Professor: Matthew Waters By Erin Pevan November 21, 2006 The stories of Arthurian literary tradition have provided our modern age with gripping tales of chivalry, adventure, and betrayal. King Arthur remains a hero of legend in the annals of the British Isles. However, one question remains: did King Arthur actually exist? Early medieval historical sources provide clues that have identified various figures that may have been the template for King Arthur. Such candidates such as the second century Roman general Lucius Artorius Castus, the fifth century Breton leader Riothamus, and the sixth century British leader Ambrosius Aurelianus hold high esteem as possible candidates for the historical King Arthur. Through the analysis of original sources and authors such as the Easter Annals, Nennius, Bede, Gildas, and the Annales Cambriae, parallels can be established which connect these historical figures to aspects of the Arthur of literary tradition. -

The Arthurian Legend Now and Then a Comparative Thesis on Malory's Le Morte D'arthur and BBC's Merlin Bachelor Thesis Engl

The Arthurian Legend Now and Then A Comparative Thesis on Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur and BBC’s Merlin Bachelor Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University Student: Saskia van Beek Student Number: 3953440 Supervisor: Dr. Marcelle Cole Second Reader: Dr. Roselinde Supheert Date of Completion: February 2016 Total Word Count: 6000 Index page Introduction 1 Adaptation Theories 4 Adaptation of Male Characters 7 Adaptation of Female Characters 13 Conclusion 21 Bibliography 23 van Beek 1 Introduction In Britain’s literary history there is one figure who looms largest: Arthur. Many different stories have been written about the quests of the legendary king of Britain and his Knights of the Round Table, and as a result many modern adaptations have been made from varying perspectives. The Cambridge Companion to the Arthurian Legend traces the evolution of the story and begins by asking the question “whether or not there ever was an Arthur, and if so, who, what, where and when.” (Archibald and Putter, 1). The victory over the Anglo-Saxons at Mount Badon in the fifth century was attributed to Arthur by Geoffrey of Monmouth (Monmouth), but according to the sixth century monk Gildas, this victory belonged to Ambrosius Aurelianus, a fifth century Romano-British soldier, and the figure of Arthur was merely inspired by this warrior (Giles). Despite this, more events have been attributed to Arthur and he remains popular to write about to date, and because of that there is scope for analytic and comparative research on all these stories (Archibald and Putter). The legend of Arthur, king of the Britains, flourished with Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain (Monmouth). -

Tolkien's Treatment of Dragons in Roverandom and Farmer Giles of Ham

Volume 34 Number 1 Article 8 10-15-2015 "A Wilderness of Dragons": Tolkien's Treatment of Dragons in Roverandom and Farmer Giles of Ham Romuald I. Lakowski MacEwan University in Edmonton, Canada Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lakowski, Romuald I. (2015) ""A Wilderness of Dragons": Tolkien's Treatment of Dragons in Roverandom and Farmer Giles of Ham," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 34 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol34/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract An exploration of Tolkien’s depictions of dragons in his stories for children, Roverandom and Farmer Giles of Ham. Draws on “On Fairy-stories,” the Beowulf lecture, the Father Christmas letters, and a little-known “Lecture on Dragons” Tolkien gave to an audience of children at the University Museum in Oxford, as well as source Tolkien would have known: Nennius, The Fairy Queene, and so on. -

Die Fledermaus by JOHANN STRAUSS September 14 - 29, 2019 PRESS KIT

Opera SAN JOSÉ 2019 | 2020 SEASON Die Fledermaus BY JOHANN STRAUSS September 14 - 29, 2019 PRESS KIT Die Fledermaus OPERETTA IN THREE ACTS MUSIC by Johann Strauss LIBRETTO by Karl Haffner and Richard Genée First performed April 5, 1874 in Vienna SUNG IN GERMAN WITH ENGLISH DIALOGUE AND ENGLISH SUPERTITLES. Performances of Die Fledermaus are made possible in part by a Cultural Affairs grant from the City of San José. PERFORMANCE SPONSORS 9/14: Michael & Laurie Warner 9/22: Jeanne L. McCann PRESS CONTACT Chris Jalufka Communications Manager Box Office (408) 437-4450 Direct (408) 638-8706 [email protected] OPERASJ.ORG For additional information go to https://www.operasj.org/about-us/press-room/ CAST Adele Elena Galván Rosalinde Maria Natale Alfredo Alexander Boyer von Eisenstein Eugene Brancoveanu Dr. Blind Mason Gates Dr. Falke Brian James Myer Frank Nathan Stark Ida Ellen Leslie Prince Orlofsky Stephanie Sanchez Frosch Jesse Merlin COVERS Amy Goymerac, Adele Jesse Merlin, Frank Marc Khuri-Yakub, Alfredo Melissa Sondhi, Ida Andrew Metzger, von Eisenstein Anna Yelizarova, Prince Orlofsky Jeremy Ryan, Dr. Blind Lance LaShelle, Frosch J. T. Williams, Dr. Falke *Casting subject to change without notice 4 Opera San José CHORUS SOPRANOS ALTOS Jannika Dahlfort Megan D'Andrea Rose Taylor Taylor Dunye Angela Jarosz Amy Worden Deanna Payne Anna Yelizarova Melissa Sondhi TENORS BASS Nicolas Gerst Carter Dougherty Marc Khuri-Yakub Michael Kuo Andrew Metzger James Schindler AJ Rodriguez J. T. Williams Jeremy Ryan SUPERNUMERARIES Torie Charvez Samuel Hoffman Hannah Fuerst Chris Tucker DANCERS Lance LaShelle AJ Rodriguez Deanna Payne Alysa Grace Reinhardt courtesy of The New Ballet Company Sally Virgilo Emmett Rodriguez courtesy of The New Ballet Company Die Fledermaus Press Kit 5 ARTISTIC TEAM CONDUCTORS Michael Morgan Christopher James Ray (conducts 9/19 & 9/22) STAGE DIRECTOR Marc Jacobs ASSISTANT STAGE DIRECTOR Tara Branham SET DESIGNER Charlie Smith COSTUME DESIGNER Cathleen Edwards LIGHTING DESIGNER Pamila Z. -

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci Filozofická

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Michaela Švachová The Evolution of Merlin: Changing Views in Literature and Film Bakalářská práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. David Livingstone, Ph.D. Olomouc 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím literatury a pramenů uvedených v bibliografii. V Olomouci dne: Podpis: ............................................... Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. David Livingstone, Ph.D. for his kind support, guidance and patience. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 6 2 MERLIN IN LITERATURE AND ON THE SCREEN ......................................... 8 2.1 Merlin in High and Late Medieval Chronicles ............................................. 8 2.2 Merlin in Medieval Romance ....................................................................... 9 2.3 Merlin from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries ...................... 11 2.4 Merlin in the Twentieth Century ................................................................ 12 2.5 Merlin on the Screen................................................................................... 14 3 GEOFFREY OF MONMOUTH ........................................................................... 16 3.1 The Origin of Merlin and His Name .......................................................... 17 3.2 Merlin in The History of the Kings of Britain............................................ -

LEGENDS of the ROUND TABLE by JEFF POSSON

LEGENDS OF THE ROUND TABLE by JEFF POSSON 2 LEGENDS OF THE ROUND TABLE SETTING The forests of England in the Middle Ages. A Lake with magic in its waters. CHARACTERS Merlin – A wizard Morgan Le Fay – An enchantress who likes to make fun of Merlin King Arthur- A king, Morgan Le Fey’s brother Sir Bedivere- A knight The Black Knight- A knight, a bit of a bully Sir Gawain- A knight The Green Knight- A knight, has a magical talent Sir Galahad- A knight The Lady of the Lake- A mystical goddess of the water Villager- Running from a dragon Scene 1 MERLIN Oh a legend is sung! Of when England was young And Knights were brave and.... (MORGAN runs on because she is tired of MERLIN’S singing.) MORGAN STOP! MERLIN What? MORGAN !Stop singing! I’m trying to cast a spell and it is INCREDIBLY distracting. MERLIN! Oh come now Morgan, it is not that distracting. MORGAN! It is, it really is. You may be the most famous wizard in history, Merlin, but your pitch is all over the place. MERLIN! 3 Fine, I’ll stop.... wait, what spell are you casting, Morgan Le Fey? Are you up to mischief again? MORGAN Oh yes, without a doubt. Mischief is what I do. MERLIN Well, you should stop it. ! MORGAN Pardon me? Do youth think I need your permission to do anything? MERLIN Well... no but...! MORGAN! No buts Merlin. This is my island you’re currently sitting on. Avalon, the isle of Apples. My island, my rules, I can do what I want.