Resources and Energy Quarterly June 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

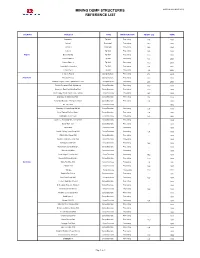

Mining Dump Structures Reference List

MINING DUMP STRUCTURES UPDATE OCTOBER 2012 REFERENCE LIST COUNTRY PROJECT TYPE MAIN FUNCTION HEIGHT [m] YEAR Luzamba Tip Wall Processing 11,4 1992 Catoca I Dump wall Processing 19,0 1995 Catoca II Dump wall Processing 16,0 1995 Catoca Tip Wall Processing 10,5 1996 Angola Escom Mining Tip Wall Processing 11,0 2002 Catoca Phase 1 Tip Wall Processing 13,6 2006 Catoca Phase 2 Tip Wall Processing 13,0 2006 Jopro 004 – Consulmet Tip Wall Processing 9,0 2007 Consulmet 2 Tip Wall Processing 9,0 2008 Veladero Project Dump structure Processing 27,8 2005 Argentina Pirquitas Project Dump structure Processing 18,0 2009 Veladero Project - Plant Expansion 85 KTPD Dump structure Processing 28,5 2009 Eastern Deepdale Pocket/Abutment Dump Structure Processing 16,0 1980 Saxonvale Raw Coal Handling Plant Dump Structure Processing 12,0 1981 Rom Hopper Walls Pacific Coal - Tarong Dump Structure Processing 19,5 1982 Boundary Hill Inpit Dump Wall - Dump Structure Processing 7,8 1982 Load Out Structure - Kangaroo Island Dump Structure Processing 6,0 1982 Mt. Tom Price Dump Structure - - 1982 Boundary Hill Inpit Dump Wall #2 Dump Structure Processing 8,0 1983 Kress Tipping Platform Stage I Dump Structure Processing 4,9 1984 Paddington Gold Project Dump Structure Processing 14,3 1984 Cork Tree Well Gold Mine Dump Wall Dump Structure Processing - 1985 Dump Wall - Cue Dump Structure Processing 8,3 1986 Telfer Mine Dump Structure Processing - 1986 Howick Colliery Temp Dump Wall Dump Structure Processing 8,4 1986 Wiluna Mine Dump Wall Dump Structure Processing - 1986 -

Telfer W with Pr 800,000 Copper Signific Resourc

4420 Newcrest Cover 04 6pp 16/9/04 9:52 AM Page 2 Telfer will be the largest gold mine in Australia, with projected annual production of more than 800,000 ounces of gold and 30,000 tonnes of copper for 24 years, positioning Newcrest as a significant and profitable Australian-based resources business. Newcrest Mining Limited Newcrest – The Sustainable Section 5 Resource Business 1 Sustainability and People 38 Section 1 Health and Safety 40 Our Results 2 Environment 42 Human Resources 43 Performance in Brief 2 Chairman’s Review 4 Section 6 ABN: 20 005 683 625 ABN: Managing Director and Corporate Governance 44 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 5 Board of Directors 45 Newcrest Senior Management 10 Corporate Governance 46 Financial Report 11 Section 7 Section 2 Concise Annual Report 2004 Financials 49 Operations 12 Directors’ Report 50 Cadia Valley Operations 14 Management Discussion and Analysis Ridgeway Gold/Copper Mine 14 of the Financial Statements 56 Cadia Hill Gold/Copper Mine 16 Statement of Financial Performance 58 Toguraci Gold Mine 19 Statement of Financial Position 59 Section 3 Statement of Cash Flows 60 Projects 22 Notes to the Concise Financial Report 61 Directors’ Declaration 68 Telfer Gold/Copper Project 24 Independent Audit Report 69 Cracow 26 Cadia East 28 Shareholder Information 70 Boddington Expansion Project 29 Five Year Summary 72 Section 4 Corporate Directory IBC Exploration 30 Strategy and Review 32 Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves 34 Newcrest Mining Limited Newcrest ABN: 20 005 683 625 Notice of Meeting Notice is hereby given that the 24th Annual General Newcrest Mining Limited Meeting will be held at the Hyatt Regency Hotel, Concise Annual Report 2004 99 Adelaide Terrace, Perth, Western Australia on Wednesday 27 October 2004 at 9.30am. -

A Case Study of Newmont Boddington Gold Mine in Western Australia

Mine Closure 2012 — A.B. Fourie and M. Tibbett (eds) © 2012 Australian Centre for Geomechanics, Perth, ISBN 978-0-9870937-0-7 doi:10.36487/ACG_rep/1208_24_Amoah Long term closure planning for an evolving mine site – a case study of Newmont Boddington Gold Mine in Western Australia K. De Sousa Newmont Asia Pacific, Australia N. Amoah Newmont Asia Pacific, Australia Abstract Newmont Boddington Gold (NBG) mine is located 12 km northwest of the town of Boddington and about 120 km southeast of Perth in Western Australia (WA). Open pit mining of an oxide gold resource commenced at the operations in 1987. In 2008, NBG undertook an expansion program to increase future gold production to one million ounces per annum, potentially becoming the largest gold mine in Australia. Critical to the life cycle of such a large mining operation is the need to ensure that mine closure is well planned in advance and consistently managed throughout operation to minimise future liabilities. For example, the large quantities of waste (waste rock estimated to be over one billion tonnes over the life of the mine), vast open pits and areas for tailings storage and site operational facilities, geographically and ecologically sensitive location and socio-economic issues will all become significant legacy factors during mine closure and post closure stages. To mitigate closure liabilities, Newmont’s internal guidelines have strict requirements for the development and review of closure plans at all stages of mine life with annual analyses of closure liability costs. This is to ensure consistency with life of mine (LOM) plans, changes in operations, stakeholder expectations, regulatory requirements etc. -

Boddington Gold Mine - Extended Basement Operation and Changes to Existing Environmental Conditions

Boddington gold mine - Extended basement operation and changes to existing environmental conditions Worsley Alumina Pty Ltd Report and recommendations of the Environmental Protection Authority Environmental Protection Authority Perth, Western Australia Bulletin 850 April 1997 ISBN. 0 7309 8027 8 ISSN. 1030 - 0120 Summary This report is to provide Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) advice and recommendations to the Minister for the Environment on the environmental factors relevant to a proposal by Worsley Alumina Ply Ltd (Worsley), through the Boddington Gold Mine (BGM) joint venture, to modify the approvals relating to the company's existing mining operations and to mine basement ore in the same location as Worsley's Boddington Gold Mine. The proposal envisages substantial extension of basement ore mining, the mining of minor oxide ore deposits outside the existing mining area, the construction of an additional residue disposal area, an increase in ore processing and the release of excess water to the Hotham River and Thirty-Four Mile Brook. It is the EPA's opinion that the following are the environmental factors relevant to the proposal: a) declared rare flora, priority flora and vegetation communities; b) threatened fauna, specially protected fauna and priority fauna; c) water resource quality; d) water resource quantity; e) gaseous emissions including greenhouse gases and odours; f) System 6 recommendation area C42 (Duncan MPA); g) landform; and h) mechanisms for environmental management. The EPA is of the view that the proposal should be subject to the environmental conditions which cunently apply to the existing gold mine except where the following recommendations or procedures supersede those conditions. -

Newmont Boddington Gold Closure Plan

Newmont Boddington Gold Closure Plan M70/21, M70/22, M70/23, M70/24, M70/25, M70/564, M70/799, M70/1031, ML264SA(1), ML264SA(2), G70/215, G70/218, G70/219, L70/28, L70/95, L70/96 Submission Date December 2012 Version Number CR35945 Contact Details Javier Brodalka, Environment Manager Phone: (08) 9883 4251 Email: [email protected] Date Revision Description of Originator Reviewer(s) Approval Revision December ‐ ‐ K. De Sousa M. Durack, S. J. Brodalka 2012 Myles, R. Kok, A. James Newmont Boddington Gold – Closure Plan Closure Plan Checklist No. Mine Closure Plan Checklist Y/N/NA Section Comments 1 Has the Checklist been endorsed by a senior Y Checklist representative within the tenement holder/ operating company? 2 How many copies were submitted to DMP? Hard copies = 2 Electronic copies = 1 Cover Page, Table of Contents 3 Does the cover page include: Y Cover Page Project title Company name Contact details (including telephone numbers and email addresses) Document ID and version number Date of submission 4 Has a Table of Contents been provided? Y Table of Contents Scope and Project Summary 5 State why the MCP is submitted. Y 1.2 6 Does the project summary include: Y Section 2 Land ownership details 2.2 Location of the project 2.1 Comprehensive site plans 2.4 Background information on the history 2.3 and status of the project Legal Obligations and Commitments 7 Has a consolidated summary or registers of Y Section 3 Appendices 1‐3 closure obligations and commitments been included? Data Collection and Analysis 8 Has information -

Independent Specialist Report on the Mineral Assets Held by Avenira Limited

Independent Specialist Report on the mineral assets held by Avenira Limited Report Prepared for RSM Corporate Australia Pty Ltd Report Prepared by SRK Consulting (Australasia) Pty Ltd AVE001 August 2019 SRK Consulting Page i Independent Specialist Report on the mineral assets held by Avenira Limited Avenira Limited Suite 19, 100 Hay Street, Subiaco WA 6008 RSM Corporate Australia Pty Ltd Level 32/2, The Esplanade, Perth WA 6000 SRK Consulting (Australasia) Pty Ltd Level 1, 10 Richardson Street, West Perth WA 6005 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.asia-pacific.srk.com Tel: +61 8 9288 2000 Fax: +61 8 9288 2001 SRK Project Number: AVE001 August 2019 Compiled by Peer Reviewed by Jeames McKibben Karen Lloyd Principal Consultant Principal Associate Consultant Email: [email protected] Authors: I Baidoo; L Collin; S McEwing; S Walsh; R Getty; M Davis MCKI/LLOY/wulr AVE001_RSM_Avenira ISR_Rev2 15 August 2019 SRK Consulting Page ii Executive Summary Avenira Limited (Avenira or the Company) has entered into an agreement for the proposed sale of the Baobab Phosphate Project (the Project) in the Republic of Senegal to related parties of the Company (Proposed Transaction). The Wonarah Project in Australia’s Northern Territory is to remain with the Company post transaction. Once the proposed sale is complete, the Company intends to review its holding in the Wonarah Project, including whether to commence a Scoping Study during the December 2019 quarter. RSM Corporate Australia Pty Ltd (RSM) has been appointed by Avenira to provide an Independent Expert Report (IER) in relation to the Proposed Transaction. -

Decoding Mafic Dykes in Southern Yilgarn and East Antarctica: Implications for the Supercontinent Cycle

Faculty of Science and Engineering School of Earth and Planetary Sciences Decoding Mafic Dykes in Southern Yilgarn and East Antarctica: Implications for the Supercontinent Cycle Jutta Camilla Stark This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University November 2018 DECLARATION To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgement has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. The author acknowledges that copyright of published works contained within this thesis resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I warrant that I have obtained, where necessary, permission from the copyright owners to use any third- party copyright material reproduced in the thesis (e.g. questionnaires, artwork, unpublished letters), or to use any of my own published work (e.g. journal articles) in which the copyright is held by another party (e.g. publisher, co-author). 22 November 2018 Jutta Camilla Stark Date i ABSTRACT Mafic dyke swarms are ubiquitous in cratons worldwide and preserve snapshots of their tectonic and magmatic evolution. Mafic dykes also provide important targets for paleomagnetic studies and act as barcodes in paleogeographic reconstructions. Their utility is often hampered by the lack of high precision geochronology because dating mafic rocks can be difficult due to their mineralogy. This PhD study applies a two-step U-Pb geochronology technique to date suboptimal samples and presents the discoveries of three previously unknown mafic dykes swarms in southwestern Yilgarn Craton and the first U-Pb age for a mafic dyke swarm at Bunger Hills in East Antarctica. -

Boddington Report

SHIRE OF BODDINGTON SUB-REGIONAL ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY ANALYSIS Shire of Boddington Sub-regional Economic Opportunity Analysis Executive Summary The Peel Regional Investment Framework sets out the vision, objectives and strategies for the Peel region to 2050. Identified within the Framework is the need for sub-regional economic analysis to aid sub-regions of the Peel to engage in innovation, economic diversification and to continue to meet the needs of a growing population. This report provides sub-regional data and preliminary economic opportunity analysis for the Shire of Boddington to aid in identifying specific opportunities for development in this locality and potential related projects across the region. Key Findings • Population & Demographics: While Boddington’s population has grown by roughly 28% over the last decade, resident numbers have been in decline since 2012. Boddington has a younger population compared to the wider region, with a median age of 39 (two years younger than the Peel average) and a higher instance of young families. By current growth rates Boddington’s population will increase by 25% in 2031, exceeding WAPC population projections. • Employment & Labour Force: Boddington is characterised by very low unemployment and healthy labour force participation. 80% of Boddington residents are employed within the Shire, this is partly attributable to a large percentage of Boddington residents being employed in the mining industry. The Mining and Construction industries provide 70% of all available jobs in the LGA, attracting residents of other localities to work in Boddington. A very high self-containment rate in Health Care implies there is a skills mismatch between the residents’ skills and available employment in this industry in the Shire. -

UG Ore Mined 60 14 50 12 40 10 8

Consistently Delivering On Commitments For personal use only November 26, 2015 Waihi Site Visit Innovation • Performance • Growth Cautionary and Technical Statements Cautionary Notes - Information Purposes Only The information contained in this presentation is provided by OceanaGold Corporation (“OGC”) for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to issue or arrange to issue, or the solicitation of an offer to issue, securities of OGC or other financial products. The information contained herein is not investment or financial product advice and has been prepared without taking into account the investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any particular person. The views, opinions and advice provided in this presentation reflect those of the individual presenters only. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the fairness, accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information, opinions and conclusion contained in this presentation. To the maximum extent permitted by law, none of OGC or any of its directors, officers, employees or agents accepts any liability, including, without limitation, any liability arising out of fault or negligence, for any loss arising from the use of the information contained in this presentation. Furthermore, this presentation does not constitute an offer of shares for sale in the United States or to any person that is, or is acting for the account or benefit of, any U.S. person (as defined in Regulation S under the United States Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the "Securities Act")) ("U.S. Person"), or in any other jurisdiction in which such an offer would be illegal. OGC’s shares have not been and will not be registered under the Securities Act. -

High-Grade Gold Underexplored Terrain

Craton Gold High-Grade Gold Underexplored Terrain JulyCraton 2016 Gold Craton Gold Pty Ltd www.corporategeosciencegroup.com Disclaimer. Cautionary Statement This Document provides a summary of Craton Gold Pty Ltd (ACN 609 094 653) (“CRT”). This Document is not, and should not be, construed to represent any form of prospectus or formal support to any capital raising activities as outlined in Section 708 of the Corporations Act. It is supplied for the benefit of those with an interest in CRT, not as specific investment advice to any particular party or person. Forward Looking Statement Whilst based on information from sources considered reliable, CRT does not represent, warrant or guarantee, expressly or impliedly, that the information in this document and presentation is complete or accurate. To the maximum extent permitted by law, CRT disclaims any responsibility to inform any recipient of this document and presentation of any matter that subsequently comes to our notice, which may affect any of the information contained in this document and presentation. Competent Person Statement Information herein relating to Exploration Targets and Results is based on information compiled by Drs Oliver Kreuzer and Kris Butera, who Members of The Australian Institute of Geoscientists (AIG) and The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (AusIMM), and Dr Amanda Buckingham, who is a Member of The Australian Society of Exploration Geophysicists (ASEG). Drs Kreuzer, Butera and Buckingham have more than 15 years experience relevant to the style of mineralisation and type of deposit being reported and to the activity which they are undertaking to qualify as a Competent Persons as defined in the 2012 Edition of the 'Australasian Code for Reporting of exploration Results, Minerals Resources and Ore Reserves' (the JORC Code). -

Prospect Magazine March

WESTERN AUSTRALIA’S INTERNATIONAL RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT MAGAZINE March 2014 – May 2014 $3 (inc GST) SETTING THE STANDARD Roy Hill continues to break new ground Print post approved PP 665002/00062 DEPARTMENT OF STATE DEVELOPMENT International Trade and Investment 1 Adelaide Terrace East Perth, Western Australia 6004 • AUSTRALIA Tel: +61 8 9222 0566 • Fax: +61 8 9222 6151 Email: [email protected] www.dsd.wa.gov.au INTERNATIONAL OFFICES Europe European Office • 5th floor, The Australia Centre Corner of Strand and Melbourne Place London WC2B 4LG • UNITED KINGDOM Tel: +44 20 7240 2881 • www.watoindia.in In recent years Africa has become an increasingly popular destination for resources investment, with major mining companies attracted by the continent’s rich mineral India — Mumbai reserves and affordable operating environment. Western Australian Trade Office 93 Jolly Maker Chambers No 2 This growth presents Western Australia with an exciting opportunity to become a 9th floor, Nariman Point • Mumbai 400 021 • INDIA leading exporter in mining skills, technology and knowledge. Already, more than Tel: +91 22 6630 3973 • Fax: +91 22 6630 3977 160 Western Australian mining companies operate hundreds of projects across 33 African countries. Indonesia — Jakarta Early this year I travelled to South Africa to speak at the annual Investing in African Western Australia Trade Office Level 48, Wisma 46, Jalan Jenderal Sudirman Kavling 1, Mining Indaba conference, and the central message I delivered to leaders from the Jakarta Pusat 10220 • INDONESIA many African nations in attendance was to ensure they receive a fair return for their country’s minerals (story page 2). -

AUSTRALIAN ARCHEAN MAFIC-ULTRAMAFIC MAGMATIC EVENTS Sheet 1 of 2 Broome

AUSTRALIAN ARCHEAN MAFIC-ULTRAMAFIC MAGMATIC EVENTS Sheet 1 of 2 Broome 114° 120° 126° 132° 138° 120° 130° 140° 150° 120° Sheet 1: Map of Australian Archean Mafic-Ultramafic Magmatic Events, Archean Mafic-Ultramafic Magmatic Events 18° 10° Time–Space–Event Chart 10° Sheet 2: Maps of Interpreted Distribution, Characterisation, and Nickel Archean Magmatic Events (AME) are defined from the published ages of mafic and AME 17 Resources of Archean Mafic-Ultramafic Rocks in the ultramafic rocks in each province and their temporal and spatial relationships are A AME 6 Port Hedland Yilgarn Craton summarised in the 'Time–Space–Event' Chart. Time-equivalent magmatism in different AME 6 a e an provinces does not necessarily imply cogenetic magmatism. The informal event names are rr Undefined AME 3 B Te AME 3 West Pilbara Mount Isa Locations of additional ages and other geological data e ra C taken from dated examples n AME 2 ba a C Terrane NORTHERNil TERRITORY r P East Pilbara (arranged on 1:5 000 000 map from north to south) r Dampier AME 13 AME 8 l AME 2 AME 17 AME 6 e D AME 6 a D T tr Terrane AME 16 Bradley Event AME 6 (mu): ~3115 Ma; a Port Hedland Undefined en A ra AME 16 C PILBARA a Dominantly mafic-ultramafic rock units are shown with bold colours a AME 4 b Undefined AME 4 3117 ± 3 Ma (SHRIMP U-Pb zircon) tuff interbedded with basalt of Woodbrook Formation, ilb CRATON AME 6 AME 16 AME 6 AME 6 West Pilbara P East Pilbara F Woodbrook Homestead, Pilbara Craton b Terrane AME 8 F Terrane B al PILBARA ntr AME 13 HAMERSLEY 20° Subordinate mafic-ultramafic