Bulgaria's Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia

XII. The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia by Iakovos D. Michailidis Most of the reports on Greece published by international organisations in the early 1990s spoke of the existence of 200,000 “Macedonians” in the northern part of the country. This “reasonable number”, in the words of the Greek section of the Minority Rights Group, heightened the confusion regarding the Macedonian Question and fuelled insecurity in Greece’s northern provinces.1 This in itself would be of minor importance if the authors of these reports had not insisted on citing statistics from the turn of the century to prove their points: mustering historical ethnological arguments inevitably strengthened the force of their own case and excited the interest of the historians. Tak- ing these reports as its starting-point, this present study will attempt an historical retrospective of the historiography of the early years of the century and a scientific tour d’horizon of the statistics – Greek, Slav and Western European – of that period, and thus endeavour to assess the accuracy of the arguments drawn from them. For Greece, the first three decades of the 20th century were a long period of tur- moil and change. Greek Macedonia at the end of the 1920s presented a totally different picture to that of the immediate post-Liberation period, just after the Balkan Wars. This was due on the one hand to the profound economic and social changes that followed its incorporation into Greece and on the other to the continual and extensive population shifts that marked that period. As has been noted, no fewer than 17 major population movements took place in Macedonia between 1913 and 1925.2 Of these, the most sig- nificant were the Greek-Bulgarian and the Greek-Turkish exchanges of population under the terms, respectively, of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and the 1923 Lausanne Convention. -

CULTURAL HERITAGE in MIGRATION Published Within the Project Cultural Heritage in Migration

CULTURAL HERITAGE IN MIGRATION Published within the project Cultural Heritage in Migration. Models of Consolidation and Institutionalization of the Bulgarian Communities Abroad funded by the Bulgarian National Science Fund © Nikolai Vukov, Lina Gergova, Tanya Matanova, Yana Gergova, editors, 2017 © Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Studies with Ethnographic Museum – BAS, 2017 © Paradigma Publishing House, 2017 ISBN 978-954-326-332-5 BULGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ETHNOLOGY AND FOLKLORE STUDIES WITH ETHNOGRAPHIC MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE IN MIGRATION Edited by Nikolai Vukov, Lina Gergova Tanya Matanova, Yana Gergova Paradigma Sofia • 2017 CONTENTS EDITORIAL............................................................................................................................9 PART I: CULTURAL HERITAGE AS A PROCESS DISPLACEMENT – REPLACEMENT. REAL AND INTERNALIZED GEOGRAPHY IN THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MIGRATION............................................21 Slobodan Dan Paich THE RUSSIAN-LIPOVANS IN ITALY: PRESERVING CULTURAL AND RELIGIOUS HERITAGE IN MIGRATION.............................................................41 Nina Vlaskina CLASS AND RELIGION IN THE SHAPING OF TRADITION AMONG THE ISTANBUL-BASED ORTHODOX BULGARIANS...............................55 Magdalena Elchinova REPRESENTATIONS OF ‘COMPATRIOTISM’. THE SLOVAK DIASPORA POLITICS AS A TOOL FOR BUILDING AND CULTIVATING DIASPORA.............72 Natália Blahová FOLKLORE AS HERITAGE: THE EXPERIENCE OF BULGARIANS IN HUNGARY.......................................................................................................................88 -

1 Curriculum Vitae by Konstantinos Moustakas 1. Personal Details

Curriculum vitae by Konstantinos Moustakas 1. Personal details Surname : MOUSTAKAS Forename: KONSTANTINOS Father’s name: PANAGIOTIS Place of birth: Athens, Greece Date of birth: 10 October 1968 Nationality: Greek Marital status: single Address: 6 Patroklou Str., Rethymnon GR-74100, Greece tel. 0030-28310-77335 (job) e-mail: [email protected] 2. Education 2.1. Academic qualifications - PhD in Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK), 2001. - MPhil in Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK), 1993. - First degree in History, University of Ioannina (Greece), 1990. Mark: 8 1/52 out of 10. 2.2. Education details 1986 : Completion of secondary education, mark: 18 9/10 out of 20. Registration at the department of History and Archeology, University of Ioannina (Greece). 1990 (July) : Graduation by the department of History and Archeology, University of Ioannina. First degree specialization: history. Mark: 8 1/52 out of 10. 1991-1992 : Postgraduate studies at the Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK). Program of study: MPhil by research. Dissertation title: Byzantine Kastoria. Supervisor: Professor A.A.M. Bryer. Examinors: Dr. J.F. Haldon (internal), Dr. M. Angold (external). 1 1993 (July): Graduation for the degree of MPhil. 1993-96, 1998-2001: Doctoral candidate at the Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK). Dissertation topic: The Transition from Late Byzantine to Early Ottoman Southeastern Macedonia (14th – 15th centuries): A Socioeconomic and Demographic Study Supervisors: Professor A.A.M. Bryer, Dr. R. Murphey. Temporary withdrawal between 30-9-1996 and 30-9-1998 due to compulsory military service in Greece. -

Béatrice Knerr (Ed.) Transfers from International Migration

U_IntLabMig8_neu_druck 17.12.12 08:19 Seite 1 8 Béatrice Knerr (Ed.) Over the early 21st century the number of those living in countries in which they were not born has strongly expanded. They became international mi- grants because they hope for jobs, livelihood security, political freedom, or a safe haven. Yet, while the number of those trying to settle in richer coun- tries is increasing, entry hurdles mount up, and host countries become more selective. While low-skilled migrants meet rejection, highly qualified are welcome. All this hold significant implications for the countries and families the migrants come from, even more so as most of them keep close relations to their origin, and many return after a longer or shorter period of time. Some settle down comfortably, others struggle each day. Some return to their home country, others stay for good. Some loose connection to rel- atives and friends, others support them by remittances for livelihood secu- International Labor Migration/// Series edited by Béatrice Knerr 8 rity and investment. In any case, most of these international migrants are – explicitly or not–involved in various stabilization strategies, be it by house- hold/family agreements, government efforts to attract valuable human capital, or sheer expectations by different actors. Transfers from This volume intends to span this spectrum by presenting impressive case studies covering essential facets of international migrants’ relationships International Migration: within their families and societies of origin. Each case study represents an essential type of linkage, starting with financial remittances, for livelihood security or investment purposes, over social remittances, up to political in- fluence of the Diaspora, covering the family/household, community and A Strategy of Economic and Social Stabilization country level. -

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-Linguistic Status : a Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-linguistic Status: A Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany by Ted Cicholi RN (Psych.), MA. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Political Science School of Government 22 September 2004 Disclaimer Although every effort has been taken to ensure that all Hyperlinks to the Internet Web sites cited in this dissertation are correct at the time of writing, no responsibility can be taken for any changes to these URL addresses. This may change the format as being either underlined, or without underlining. Due to the fickle nature of the Internet at times, some addresses may not be found after the initial publication of an article. For instance, some confusion may arise when an article address changes from "front page", such as in newspaper sites, to an archive listing. This dissertation has employed the Australian English version of spelling but, where other works have been cited, the original spelling has been maintained. It should be borne in mind that there are a number of peculiarities found in United States English and Australian English, particular in the spelling of a number of words. Interestingly, not all errors or irregularities are corrected by software such as Word 'Spelling and Grammar Check' programme. Finally, it was not possible to insert all the accents found in other languages and some formatting irregularities were beyond the control of the author. Declaration This dissertation does not contain any material which has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any tertiary institution. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

FEBRUARY 2015 ISSUE 21 Dear Readers, Welcome to Issue 21 Of

FEBRUARY 2015 ISSUE 21 Dear Readers, Welcome to issue 21 of the Think Tank Review compiled by the EU Council Library*. It references papers published in January 2015. As usual, we provide the link to the full text and a short abstract. This month's Review marks two years since we started this project. The TTR began as a quick tour through the websites of a handful of think tanks in EU affairs, in order to provide Council staff with a product more structured than the occasional, and often over-looked, e-mail alert from the library. It gained ground by word of mouth, encouraging us to enlarge the range of think tanks we monitor, finding valuable sources outside Brussels and networking with fellow information specialists in EU institutions and elsewhere. To celebrate the anniversary, we look back to our virtual shelves: the Special Focus this month puts side-by-side recent publications and papers on the same subjects from early 2013. The picture that emerges, from the crisis to Euromaidan, from the Arab Spring to Brexit, is one of persistent challenges but also incremental progress, painstakingly achieved through negotiation by the EU institutions and Member States, in what some scholars now call 'deliberative intergovernmentalism'. The library team takes some pride in contributing to feed this process with diverse sources and ideas. Further in this issue, as typical at this time of the year, various organizations set out global scenarios for 2015: notably the German Marshall Fund, CIDOB, ECFR, EUISS, FRIDE; but we also found a survey of expectations for 2025 held by French and German businesspeople. -

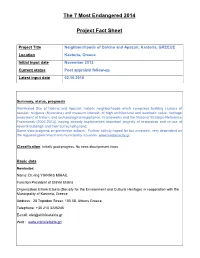

The 7 Most Endangered 2014 Project Fact Sheet

The 7 Most Endangered 2014 Project Fact Sheet Project Title Neighbourhoods of Dolcho and Apozari, Kastoria, GREECE Location Kastoria, Greece Initial input date November 2013 Current status Post appraisal follow-up Latest input date 02.10.2018 Summary, status, prognosis Nominated Site of Dolcho and Apozari, historic neighborhoods which comprises building clusters of secular, religious (Byzantine) and museum interest, of high architectural and aesthetic value, heritage monument of historic and archaeological importance. Frameworks and the National Strategic Reference Framework (2007-2013), having already implemented important projects of restoration and re-use of several buildings and their surrounding land. Some slow progress on preventive actions. Further activity hoped for but uncertain, very dependent on the regional government and municipality situation. www.kastoriacity.gr Classification: Initially good progress. No news about present times. Basic data Nominator: Name: Dr.-Ing YIANNIS MIHAIL Function President of Elliniki Etairia Organization Elliniki Etairia (Society for the Environment and Cultural Heritage) in cooperation with the Municipality of Kastoria, Greece Address : 28 Tripodon Street, 105 58, Athens Greece Telephone: +30 210 3225245 E-mail: [email protected] Web : www.ellinikietairia.gr/ Brief description: Historic neighborhoods with relevant examples of residential small buildings growing around small byzantine chapels and churches. Landscape and surrounding area with high heritage value. Owner: Public. (&Private), Bishopric (churches). 2013 data: Name: Municipality of Kastoria Administrator: (2013 data). The Municipality of Kastoria, with its own funds and resources and with European funds. Other partners: • The Regional Authority of Western Macedonia. Website: www.pdm.gov.gr • The 16th ΕΒΑ (Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities). • The Technical Chamber of Greece (ΤΕΕ). -

Kinship Terminology in Karashevo (Banat, Romania) // Slověne

Patterns and Паттерны и Mechanisms of механизмы Lexical Changes in the лексических Languages of Symbiotic изменений в языках Communities: симбиотических Kinship Terminology сообществ: термины in Karashevo родства в Карашево (Banat, Romania) (Банат, Румыния) Daria V. Konior Дарья Владимировна Конёр The Institute for Linguistic Studies Институт лингвистических исследований of the Russian Academy of Sciences Российской академии наук St. Petersburg, Russia С.-Петербург, Россия Abstract This article deals with the ethnolinguistic situation in one of the most archaic areas of language and cultural contact between South Slavic and Eastern Ro- mance populations—the Karashevo microregion in Banat, Romania. For the fi rst time, the lexical-semantic group of kinship terms in the Krashovani dia- lects from the Slavic-speaking village of Carașova and the Romanian-speak- ing village of Iabalcea is being analysed in a comparative perspective as two Цитирование: Konior D. V. Patterns and Mechanisms of Lexical Changes in the Languages of Symbiotic Communities: Kinship Terminology in Karashevo (Banat, Romania) // Slověne. 2020. Vol. 9, № 1. C. 381–411. Citation: Konior D. V. (2019) Patterns and Mechanisms of Lexical Changes in the Languages of Symbiotic Communities: Kinship Terminology in Karashevo (Banat, Romania). Slověne, Vol. 9, № 1, p. 381–411. DOI: 10.31168/2305-6754.2020.9.1.14 This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International 2020 №1 Slověne Patterns and Mechanisms of Lexical Changes in the Languages of Symbiotic Communities: 382 | Kinship Terminology in Karashevo (Banat, Romania) separate linguistic codes which “serve” the same local culture. The main goal of the research was to investigate patterns of borrowing mechanisms which could link lexical (sub)systems of spiritual culture under the conditions of in- timate language contact in symbiotic communities. -

The Rise of Bulgarian Nationalism and Russia's Influence Upon It

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it. Lin Wenshuang University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wenshuang, Lin, "The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it." (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1548. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1548 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Lin Wenshuang All Rights Reserved THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Approved on April 1, 2014 By the following Dissertation Committee __________________________________ Prof. -

The Attitude of the Communist Party of Greece and the Protection of the Greek-Yugoslav Border

Spyridon Sfetas Autonomist Movements of the Slavophones in 1944: The Attitude of the Communist Party of Greece and the Protection of the Greek-Yugoslav Border The founding of the Slavo-Macedonian Popular Liberation Front (SNOF) in Kastoria in October 1943 and in Florina the following November was a result of two factors: the general negotiations between Tito's envoy in Yugoslav and Greek Macedonia, Svetozar Vukmanovic-Tempo, the military leaders of the Greek Popular Liberation Army (ELAS), and the political leaders of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) in July and August 1943 to co-ordinate the resistance movements; and the more specific discussions between Leonidas Stringos and the political delegate of the GHQ of Yugoslav Macedonia, Cvetko Uzunovski in late August or early September 1943 near Yannitsa. The Yugoslavs’ immediate purpose in founding SNOF was to inculcate a Slavo- Macedonian national consciousness in the Slavophones of Greek Macedonia and to enlist the Slavophones of Greek Macedonia into the resistance movement in Yugoslav Macedonia; while their indirect aim was to promote Yugoslavia's views on the Macedonian Question. The KKE had recognised the Slavophones as a "SlavoMacedonian nation" since 1934, in accordance with the relevant decision by the Comintern, and since 1935 had been demanding full equality for the minorities within the Greek state; and it now acquiesced to the founding of SNOF in the belief that this would draw into the resistance those Slavophones who had been led astray by Bulgarian Fascist propaganda. However, the Central Committee of the Greek National Liberation Front (EAM) had not approved the founding of SNOF, believing that the new organisation would conduce more to the fragmentation than to the unity of the resistance forces.