APOCALYPSE Setting 1995(Quarkx)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rosenbauer Magazine 2021

€ 6,50 The Rosenbauer Magazine 2021 RETHINKING WORK. The fire department is a trailblazer for new collaborative work. ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE. How machines are getting smarter and how teamwork functions with AI. IN FOCUS: DIGITALIZATION How a fully networked vehicle is revolutionizing the fire service. Which digital technologies will make future assignments easier? And, do we still need a human workforce? 2 | The Rosenbauer Magazine IN BRIEF | 3 editorialDear readers, We are thrilled to introduce to you the new Rosenbauer magazine, ready. The current, fi rst edition of ready is dedicated to digitalization. Increasingly penetrating every corner of our lives, digitalization is gradually but steadily changing our everyday lives. Depend- ing on individual views on the matter, the term is frequently used in conjunction with words like ‘transformation’ or ‘revo- lution'. One thing is certain: the fi re service’s working environ- ment will change forever. The digitalized fi re service will be an organization with greater capabilities and new opportunities. In ready, we cast our gaze to the future of the emergency ser- vices, analyze the eff ects of societal trends on the fi re service, and highlight the relevance of new scientifi c fi ndings for work at fi re departments. Each future edition will focus on a specifi c topic and unpack its eff ects on the emergency services. Our aim is to think outside the box and show diverse perspectives to provide food for thought, provoking wider discussion and awareness within the fi re-service sector. We hope you will enjoy the read! Rethinking work. The simple click of a button reveals all the mission data and a clear overview of the Tiemon Kiesenhofer, Editor in Chief situation – the RT is Group Communication, Rosenbauer International AG revolutionizing day-to- day operations at the fi re department. -

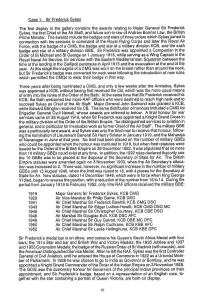

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes the First Display in the Gallery Contains

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes The first display in the gallery contains the awards relating to Major General Sir Frederick Sykes, the first Chief of the Air Staff, and future son-in-law of Andrew Bonnar Law, the British Prime Minister. The awards include the badges and stars of three orders which Sykes joined in connection with his services in command of the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force, with the badge of a CMG, the badge and star of a military division KCB, and the sash badge and star of a military division GBE. Sir Frederick was appointed a Companion in the Order of St Michael and St George on 1 January 1916, while serving as a Wing Captain in the Royal Naval Air Service, for services with the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron between the time of the landing in the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915 and the evacuation at the end of the year. At this stage the insignia of a CMG was worn on the breast rather than around the neck, but Sir Frederick’s badge was converted for neck wear following the introduction of new rules which permitted the CMGs to wear their badge in that way. Three years after being nominated a CMG, and only a few weeks after the Armistice, Sykes was appointed a KCB, without having first received the CB, which was the more usual means of entry into the ranks of the Order of the Bath. At the same time that Sir Frederick received his KCB, the Bath welcomed two more RAF officers who were destined to reach high rank and to succeed Sykes as Chief of the Air Staff: Major General John Salmond was granted a KCB, while Edward Ellington received his CB. -

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Fire Management Working Papers Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005 – Report on fires in the Baltic Region and adjacent countries by Ilkka Vanha-Majamaa March 2006 Forest Resources Development Service Working Paper FM/7/E Forest Resources Division FAO, Rome, Italy Forestry Department Disclaimer The Fire Management Working Papers report on issues addressed in the work programme of FAO. These working papers do not reflect any official position of FAO. Please refer to the FAO website (www.fao.org/forestry) for official information. The purpose of these papers is to provide early information on on-going activities and programmes, and to stimulate discussion. Comments and feedback are welcome. For further information please contact: Mr. Petteri Vuorinen, Forestry Officer (Forest Fire Management) Mr. Peter Holmgren, Chief Forest Resources Development Service Forest Resources Division, Forestry Department FAO Viale delle Terme di Caracalla I-00100 Rome, Italy e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] or: FAO Publications and Information Coordinator: [email protected] For quotation: FAO (2006). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005 – Report on fires in the Baltic Region and adjacent countries. Fire Management Working Paper 7. www.fao.org/forestry/site/fire-alerts/en © FAO 2006 FOREWORD Fires impact upon livelihoods, ecosystems and landscapes. Despite incomplete and inconsistent data, it is estimated that 350 million hectares burn each year; however, -

Plauen 1945 Bis 1949 – Vom Dritten Reich Zum Sozialismus

Plauen 1945 bis 1949 – vom Dritten Reich zum Sozialismus Entnazifizierung und personell-struktureller Umbau in kommunaler Verwaltung, Wirtschaft und Bildungswesen Promotion zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. phil. der Philosophischen Fakultät der Technischen Universität Chemnitz eingereicht von Dipl.-Lehrer Andreas Krone geboren am 26. Februar 1957 in Plauen angefertigt an der Technischen Universität Chemnitz-Zwickau Fachbereich Regionalgeschichte Sachsen betreut von: Dr. sc. phil. Reiner Groß Professor für Regionalgeschichte Sachsen Beschluß über die Verleihung des akademischen Grades Doktor eines Wissenschaftszweiges vom 31. Januar 2001 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite 0. Einleitung 4 1. Die Stadt Plauen am Ende des 2. Weltkrieges - eine Bilanz 9 2. Zwischenspiel - die Amerikaner in Plauen (April 1945 - Juni 1945) 16 2.1. Stadtverwaltung und antifaschistischer Blockausschuß 16 2.2. Besatzungspolitik in der Übergangsphase 24 2.3. Anschluß an die amerikanische Zone? 35 2.4. Resümee 36 3. Das erste Nachkriegsjahr unter sowjetischer Besatzung 38 (Juli 1945 - August 1946) 3.1. Entnazifizierung unter der Bevölkerung bis Ende 1945 38 3.2. Stadtverwaltung 53 3.2.1. Personalreform im Stadtrat 53 3.2.2. Strukturelle Veränderungen im Verwaltungsapparat 66 3.2.3. Verwaltung des Mangels 69 a) Ernährungsamt 69 b) Wohnungsamt 72 c) Wohlfahrtsamt 75 3.2.4. Eingesetzte Ausschüsse statt gewähltes Parlament 78 3.2.5. Abhängigkeit der Stadtverwaltung von der Besatzungsmacht 82 3.2.6. Exkurs: Überwachung durch „antifaschistische“ Hauswarte 90 3.3. Wirtschaft 93 3.3.1. Erste personelle Maßnahmen zur Bereinigung der Wirtschaft 93 3.3.2. Kontrolle und Reglementierung der Unternehmen 96 3.3.3. Entnazifizierung in einer neuen Dimension 98 a) Die Befehle Nr. -

Nightfighter Scenario Book

NIGHTFIGHTER 1 NIGHTFIGHTER Air Warfare in the Night Skies of World War Two SCENARIO BOOK Design by Lee Brimmicombe-Wood © 2011 GMT Games, LLC P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308, USA www.GMTGames.com © GMTGMT Games 1109 LLC, 2011 2 NIGHTFIGHTER CONTENTS SCENARIO 1: Cat’S EYE How to use this book 2 Background. September 1940. Early nightfighting relied on single-seat day fighters cruising the skies in the hope that they SCENARIO 1: Cat’S EYE 2 might find the enemy. Pilots needed “cat’s eyes” to pick out Scenario 1 Variant 2 bombers in the dark. In practice the technique resulted in SCENARIO 2: DUNAJA 3 few kills and more defending aircraft were lost due to night- flying accidents than enemy aircraft were shot down. Scenario 2 Variants 3 This scenario depicts a typical “cat’s eye” patrol during the SCENARIO 3: THE KAMMHUBER LINE 4 German Blitz on Britain. A lone Hurricane fighter is flying Scenario 3 Variants 4 over southern England on a moonlit night. SCENARIO 4: HIMMELBETT 5 Difficulty Level. Impossible. Game Length. The game ends when all bombers have exited Scenario 4 Variants 5 the map, or a bomber is shot down. SCENARIO 5: WILDE SAU 7 Sequence of Play. Ignore the Flak Phase, Radar Search Phase, Scenario 5 Variants 7 AI Search Phase and Searchlight Phase. SCENARIO 6: ZAHME SAU 8 Attacker Forces. (German) Scenario 6 Variants 8 Elements of KG 100, Luftwaffe. The attacker has three He111H bombers. SCENARIO 7: Serrate 11 Attacker Entry. One bomber enters on Turn 1, another on Scenario 7 Variants 11 Turn 5 and a final one on Turn 10. -

Imperial Airways

IMPERIAL AIRWAYS 1 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW.XV Atlanta, G-ABPI, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 2 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. G-ADSR, Ensign Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 3 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW15 Atlanta, G-ABPI, Imperial Airways, air to air, 1932. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 4 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Argosy I, G-EBLF, Imperial Airways, 1929. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 5 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, 1937. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 6 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Atlanta, G-ABTL, Astraea Imperial Airways, Royal Mail GR. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 7 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Atalanta, G-ABTK, Athena, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 8 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW Argosy, G-EBLO, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 9 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 10 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 11 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Argosy I, G-EBOZ, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 12 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW 27 Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 13 AVRO. 652, G-ACRM, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 14 AVRO. 652, G-ACRN, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 15 AVRO. Avalon, G-ACRN, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 16 BENNETT, D. C. -

Vorbemerkung

5 Vorbemerkung Im Kreis der 43 Gauleiter des „Großdeutschen Reiches“ zählte Martin Mutsch- mann zu den mächtigsten: Es gab nur wenige „politische Generale“ (Karl Höffkes), die neben der politischen Führung des Gaus auch die entscheidenden staatlichen Führungspositionen in den Händen hielten und überdies zu Hitlers frühesten Ge- folgsleuten zählten. Seit 1925 war er Gauleiter der sächsischen NSDAP, seit 1933 Reichsstatthalter und seit 1935 Ministerpräsident in Sachsen. 1939 kam der einfluss- reiche Posten eines Reichsverteidigungskommissars hinzu. Noch Anfang 1945, aus Anlass seines 20-jährigen Gauleiter-Jubiliäums, ließ sich Mutschmann von der ei- genen Presse als ein „Vorbild an Treue und Tatkraft“ würdigen. „Damals schon“, von den „Anfängen der NSDAP an“1, so verkündete ein Dresdner Blatt in Super- lativen, sei er einer der „bewährtesten und mutigsten, treuesten und einsatzbereites- ten, tatkräftigsten und fanatischsten Gefolgsmänner des Führers“ gewesen, eben: Hitlers „getreuer Paladin“. Das, was da zu Anfang 1945 etwas unfreiwillig wie ein Nachruf klang, erscheint nicht in allen Punkten übertrieben oder gar erdichtet. Mutschmann war tatsächlich ein „perfekter Nazi-Gauleiter“. Ein Urteil, das der deutsch-britische Historiker Claus-Christian W. Szejnmann so begründete: „Er war Hitler besonders treu ergeben, ein gewalttätiger Antisemit, extrem skrupellos und entschlossen.“2 Gerade weil der sächsische „Gaufürst“ vor 1945 so allgegenwärtig schien, wirkte sein beinahe spurloses Ende seltsam unbefriedigend. Dass er noch im Mai 1945 in sowjetische -

Welcome to Kunsan Air Base

Welcome to Kunsan Air Base "Home of the Wolf Pack" Dear Guest, Welcome to Wolf Pack Lodge, the newest AF Lodging facility in the ROK. Kunsan Air Base is home to the 8th Fighter Wing, also known as the "Wolf Pack," a nickname given during the command of Colonel Robin Olds in 1966. Our mission is; "Defend the Base, Accept Follow on Forces, and Take the Fight North," the warriors here do an amazing job ensuring mission success. Kunsan AB plays host to many personnel, in all branches of the service, in support of our numerous peninsula wide exercises each year. We are proud to serve all the war fighters who participate in these exercises and ensure our "Fight Tonight" capability. To ensure you have a great stay with us, I would ask that you report any problem with your room to our front desk staff immediately, so we can try to resolve the issue, and you can focus on your mission here. If any aspect of your stay is less than you would hope for, please call me at 782-1844 ext. 160, or just dial 160 from your room phone. You may also e-mail me at [email protected] , I will answer you as quickly as possible. We are required to enter each room at least every 72 hours, this is not meant to inconvenience you, but to make sure you are okay, and see if there is anything you need. If you will be working shift work while here and would like to set up a time that is best for you to receive housekeeping service, please dial 157 from your room phone, and the Housekeeping Manager would be happy to schedule your cleaning between 0800 and 1600. -

Hidden in Plain Sight: the Secret History of Silicon Valley the Genesis of Silicon Valley Entrepreneurship

Hidden in Plain Sight: The Secret History of Silicon Valley The Genesis of Silicon Valley Entrepreneurship Marc Andressen Internet Steve Jobs Personal Computers Gordon Moore Integrated Circuits Innovation Networks Hewlett & PackardDefense 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Hidden in Plain Sight: The Secret History of Silicon Valley A few caveats • Not a professional historian • Some of this is probably wrong • All “secrets” are from open-source literature Hidden in Plain Sight: The Secret History of Silicon Valley Six Short Stories Hidden in Plain Sight: The Secret History of Silicon Valley Story 1: WWII The First Electronic War Hidden in Plain Sight: The Secret History of Silicon Valley Strategic Bombing of Germany The Combined Bomber Offensive • British bombed at Night – Area Bombing • Lancaster's • Halifax • Flew at 7 - 17 thousand feet • The American’s by Day – Precision Bombing • B-17’s • B-24’s • Flew at 15 - 25 thousand feet Hidden in Plain Sight: The Secret History of Silicon Valley British and American Air War in Europe 28,000 Active Combat Planes 40,000 planes lost or damaged beyond repair: 18,000 American and 22,000 British 79,265 Americans and 79,281 British killed Hidden in Plain Sight: The Secret History of Silicon Valley Hidden in Plain Sight: The Secret History of Silicon Valley The German Air Defense System The Kammhuber Line • Integrated Electronic air defense network – Covered France, the Low Countries, and into northern Germany • Protection from British/US bomber raids – Warn and Detect – Target and Aim – Destroy Hidden -

Cr^Ltxj

THE NAZI BLOOD PURGE OF 1934 APPRCWBD": \r H M^jor Professor 7 lOLi Minor Professor •n p-Kairman of the DeparCTieflat. of History / cr^LtxJ~<2^ Dean oiTKe Graduate School IV Burkholder, Vaughn, The Nazi Blood Purge of 1934. Master of Arts, History, August, 1972, 147 pp., appendix, bibliography, 160 titles. This thesis deals with the problem of determining the reasons behind the purge conducted by various high officials in the Nazi regime on June 30-July 2, 1934. Adolf Hitler, Hermann Goring, SS leader Heinrich Himmler, and others used the purge to eliminate a sizable and influential segment of the SA leadership, under the pretext that this group was planning a coup against the Hitler regime. Also eliminated during the purge were sundry political opponents and personal rivals. Therefore, to explain Hitler's actions, one must determine whether or not there was a planned putsch against him at that time. Although party and official government documents relating to the purge were ordered destroyed by Hermann GcTring, certain materials in this category were used. Especially helpful were the Nuremberg trial records; Documents on British Foreign Policy, 1919-1939; Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918-1945; and Foreign Relations of the United States, Diplomatic Papers, 1934. Also, first-hand accounts, contem- porary reports and essays, and analytical reports of a /1J-14 secondary nature were used in researching this topic. Many memoirs, written by people in a position to observe these events, were used as well as the reports of the American, British, and French ambassadors in the German capital. -

Gesamtinhaltsverzeichnis Über Die Bände 64-87 (1993-2016)

Neues Archiv für sächsische Geschichte Gesamtinhaltsverzeichnis über die Bände 64-87 (1993–2016) bearbeitet von Jens Klingner, Frank Metasch, André Thieme und Lutz Vogel unter Mitarbeit von Christian Gründig, Kerstin Mühle, Pia Heine, Bettina Pahl, Robin Richter und Martin Schwarze Institut für Sächsische Geschichte und Volkskunde e. V. Dresden 2017 Neues Archiv für sächsische Geschichte Herausgeber Bd. 64- 69 Karlheinz Blaschke Bd. 70-72 Karlheinz Blaschke in Verbindung mit dem Institut für Sächsische Geschichte und Volkskunde e. V. Bd. 73-86 Karlheinz Blaschke; Enno Bünz; Winfried Müller; Martina Schattkowsky; Uwe Schirmer im Auftrag des Instituts für Sächsische Geschichte und Volkskunde e. V. Schriftleitung/Redaktion Bd. 64, 65 Uwe John (redaktionelle Mitarbeit) Bd. 66-69 Uwe John (Redaktion) Bd. 70-72 Uwe John (Schriftleitung) Bd. 73-80 André Thieme (Redaktion) Bd. 81 André Thieme/Frank Metasch (Redaktion) Bd. 82-86 Frank Metasch (Schriftleitung), Lutz Vogel (Rezensionen) Verlag Bd. 64-69 Verlag Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger Weimar Bd. 70-86 Verlag Ph. C. W. Schmidt Neustadt an der Aisch 2 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS A. Alphabetisches Verzeichnis der Mitarbeiter und ihrer Beiträge 4 B. Systematische Inhaltsübersicht 20 I. Quellenkunde und Forschung a. Quellen 20 b. Bibliografie 24 c. Tätigkeitsberichte 24 d. Projekte 25 II. Landesgeschichte: chronologisch a. Allgemeines 26 b. Mittelalter bis 1485 27 c. 1485 bis 1648 30 d. 1648 bis 1830 33 e. 1830 bis 1945 37 f. 1945 bis zur Gegenwart 40 III. Landesgeschichte: thematisch a. Archäologie 41 b. Siedlungsgeschichte und Landeskunde 42 c. Namenkunde 43 d. Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 44 e. Kultur- und Mentalitätsgeschichte 47 f. Geschlechtergeschichte 51 g. Schul-, Universitäts- und Bildungsgeschichte 52 h. -

England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions >> Irving V

[Home ] [ Databases ] [ World Law ] [Multidatabase Search ] [ Help ] [ Feedback ] England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions >> Irving v. Penguin Books Limited, Deborah E. Lipstat [2000] EWHC QB 115 (11th April, 2000) URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2000/115.html Cite as: [2000] EWHC QB 115 [New search ] [ Help ] Irving v. Penguin Books Limited, Deborah E. Lipstat [2000] EWHC QB 115 (11th April, 2000) 1996 -I- 1113 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION Before: The Hon. Mr. Justice Gray B E T W E E N: DAVID JOHN CADWELL IRVING Claimant -and- PENGUIN BOOKS LIMITED 1st Defendant DEBORAH E. LIPSTADT 2nd Defendant MR. DAVID IRVING (appered in person). MR. RICHARD RAMPTON QC (instructed by Messrs Davenport Lyons and Mishcon de Reya) appeared on behalf of the first and second Defendants. MISS HEATHER ROGERS (instructed by Messrs Davenport Lyons) appeared on behalf of the first Defendant, Penguin Books Limited. MR ANTHONY JULIUS (instructed by Messrs Mishcon de Reya) appeared on behalf of the second Defendant, Deborah Lipstadt. I direct pursuant to CPR Part 39 P.D. 6.1. that no official shorthand note shall be taken of this judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. Mr. Justice Gray 11 April 2000 Index Paragraph I. INTRODUCTION 1.1 A summary of the main issues 1.4 The parties II. THE WORDS COMPLAINED OF AND THEIR MEANING 2.1 The passages complained of 2.6 The issue of identification 2.9 The issue of interpretation or meaning III.