Paul Ehrlich and the Origins of His Receptor Concept

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nobel Prize in Medicine 1952 Was Awarded to Selman A

History of Мedicine of the Newest period (XX-XXI centuries). EHRLICH AND ARSPHENAMINE Paul Ehrlich In 1910, with his colleague Sahachiro Hata, conducted tests on arsphenamine, once sold under the commercial name Salvarsan. Salvarsan, a synthetic preparation containing arsenic, is lethal to the microorganism responsible for syphilis. SULFONAMIDE DRUGS In 1932 the German bacteriologist Gerhard Domagk announced that the red dye Prontosil is active against streptococcal infections in mice and humans. Soon afterward French workers showed that its active antibacterial agent is sulfanilamide. In 1928 ALEXANDER FLEMING noticed the PENICILLIN inhibitory activity of a stray mold on a plate culture of staphylococcus bacteria. In 1938 HOWARD FLORY, ERNEST CHAIN received pure penicillin. In 1945 ALEXANDER FLEMING, HOWARD FLORY, ERNEST CHAIN won the Noble Prize for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases. ANTITUBERCULOSIS DRUGS •In 1944, SELMAN WAXMAN announced the discovery of STREPTOMYCIN from cultures of a soil organism Streptomyces griseus, and stated that it was active against M. tuberculosis. •Clinincal trials confirmed this claim. •The Nobel Prize in Medicine 1952 was awarded to Selman A. Waksman •In Paris, Élie Metchnikoff had already detected the role of white blood cells in the IMMUNOLOGY immune reaction, •Jules Bordet had identified antibodies in the blood serum. •The mechanisms of antibody activity were used to devise diagnostic tests for a number of diseases. •In 1906 August von Wassermann gave his name to the blood test for syphilis, and in 1908 the tuberculin test— the skin test for tuberculosis— came into use. INSULIN •In 1921, Frederick Banting and Charles H. -

Wassermann, August Paul Von (1866-1925)

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Cumming School of Medicine Cumming School of Medicine Research & Publications 2007 Wassermann, August Paul von (1866-1925) Stahnisch, Frank W. Greenwood Stahnisch, F.: ,,Wassermann, August Paul von (1866-1925)". In: Dictionary of Medical Biography (DMB). W. F. Bynum and Helen Bynum (eds.). Westport, CO, London: Greenwood 2007, Vol. 5, p. 1290f. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/48269 Other Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca WASSERMANN, AUGUST PAUL VON (b. Bamberg, Germany, 21 February 1866; d. Berlin, Germany, 16 March 1925), clinical chemistry, serology. Wassermann was born in Bamberg and began to study medicine in the nearby university town of Erlangen, before heading to Munich, Vienna, and Strassburg. In 1888 Wassermann graduated MD at the German university of Strassburg and began to work as research assistant to Robert Koch in the Institute for Infectious Diseases of Friedrich- Wilhelms-University of Berlin. Here he was introduced to the methods of laboratory experimentation and to Koch's concept of the relevance of bacteriology for clinical medi• cine. At the Institute for Infectious Diseases, Wassermann worked on immunity phenomena related to cholera infec• tion and tried to develop antitoxins against diphtheria. As a result of these experimental investigations, he received the 'venia legendi' for hygiene in 1901. Following Paul Ehrlich's advice, Wassermann began to study the binding of toxin and antitoxin in the blood. He then investigated the differing reactions of blood groups in response to various precipitat• ing blood sera. In 1902 Wassermann was made 'Extraordi- narius' at the institute and in 1906 received the directorship of the division of experimental therapy and biochemistry. -

SCIENTIFIC REPORT 2020 for the Years 2016 to 2019 Table of Contents

SCIENTIFIC REPORT 2020 For the years 2016 to 2019 Table of Contents 3 Foreword 4 Research in Numbers 7 Strategic Vision 9 Research Pillars 10 Pillar I: Dissecting Tumour Survival Mechanisms and Tumour Microenvironment 18 Pillar II: Tracking and Targeting Minimal Residual Disease 22 Pillar III: Next Generation Molecular Imaging to Better Personalise Treatment 27 Pillar IV: Accelerating Anticancer Drug Development 33 Pillar V: Developing New Approaches to Patient Empowerment and Well-being 40 New facilities will bring new opportunities for research 41 Organisation of Research Governance Research Support Units 48 Collaborations 51 Funding Les Amis de l’Institut Bordet Research Grants 54 Visiting Medical Research Fellows (2016-2019) 55 Awards 56 Publications 2016-2019 2016-2019 (Selected Papers) Publications 2019 79 Abbreviations 2 Foreword Dominique de Valeriola General Medical Director Institut Jules Bordet is a public and academic OECI*-certified comprehensive cancer center playing an important role in cancer care, research and education, both in Belgium and internationally. Entirely dedicated to adult cancer patients since its creation in 1939, it belongs to the City of Brussels and the Université Libre de Bruxelles. Both translational and clinical research are part of the Institute’s DNA, aiming to bring research discoveries to the patient’s bedside quickly. The present 2016-2019 scientific report reflects the spirit of commitment and collaboration of the Institute’s healthcare professionals, researchers, and administrative support teams and, above all, of the patients who trust our teams and volunteer to participate in clinical trials. A concerted and well-rewarded effort has been made during these recent years to build a stronger partnership with patients in developing our clinical trials, and to establish more efficient, centralised governance and operational support for our research activities. -

Balcomk41251.Pdf (558.9Kb)

Copyright by Karen Suzanne Balcom 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Karen Suzanne Balcom Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Committee: E. Glynn Harmon, Supervisor Julie Hallmark Billie Grace Herring James D. Legler Brooke E. Sheldon Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine by Karen Suzanne Balcom, B.A., M.L.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2005 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my first teachers: my father, George Sheldon Balcom, who passed away before this task was begun, and to my mother, Marian Dyer Balcom, who passed away before it was completed. I also dedicate it to my dissertation committee members: Drs. Billie Grace Herring, Brooke Sheldon, Julie Hallmark and to my supervisor, Dr. Glynn Harmon. They were all teachers, mentors, and friends who lifted me up when I was down. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee: Julie Hallmark, Billie Grace Herring, Jim Legler, M.D., Brooke E. Sheldon, and Glynn Harmon for their encouragement, patience and support during the nine years that this investigation was a work in progress. I could not have had a better committee. They are my enduring friends and I hope I prove worthy of the faith they have always showed in me. I am grateful to Dr. -

THE BLUE CARD CALENDAR 5 7 8 1 the BLUE CARD Is a Charitable Organization That Has Been Aiding Holocaust Survivors Since 1934

THE BLUE CARD CALENDAR 5 7 8 1 THE BLUE CARD is a charitable organization that has been aiding Holocaust survivors since 1934. It is dedicated to the support of European Jewish survivors and their descendants in this country, who still suffer from the aftereffects of Nazi persecution, are sick or emotionally unstable, have been unable to achieve economic independence, or have lost it through sickness or old age; in many cases the Holocaust has deprived them of family. The Blue Card’s activities aren’t duplicated by any other Jewish welfare agencies. During the year 2019, The Blue Card distributed nearly $2.7 million. This brings the grant total since The Blue Card’s inception to over $40 million. THE BLUE CARD continues to receive four-star ratings from Charity Navigator, a distinction awarded to only four percent of all charities. The Blue Card is Better Business Bureau (BBB) accredited. THE BLUE CARD mirrors the social conscience of our community. We hope it will be important to you, and that you will remember it in your last will. Your contribution is fully tax deductible. THE BLUE CARD has been publishing this calendar for its friends and friends-to-be for more than 50 years in order to remind them, throughout the year, that there is an organization which is always ready to render assistance to our neediest. PLEASE SEE the inside back cover of this calendar for more information about The Blue Card. A copy of the most recent financial report may be obtained from The Blue Card, Inc., 171 Madison Ave. -

August Von Wassermann

August von Wassermann August Paul von Wassermann (* 21. Februar 1866 in Bamberg; † 16. März 1925 in Berlin) war ein deutscher Immunologe und Bakteriologe. Er veröffentlichte 1906 ein serologisches Verfahren zum Nachweis der Syphilis, den Wassermann-Test. Inhaltsverzeichnis Familie Leben Wissenschaftliches Werk Schriften Wassermann in der Literatur Ehrungen Literatur Weblinks August von Wassermann Einzelnachweise Familie August von Wassermann wurde als zweiter Sohn des 1910 in den erblichen Adelsstand erhobenen bayerischen Hofbankiers Angelo von Wassermann geboren und heiratete am 3. Dezember 1895[1] Alice Taussig (1874–1943), die Tochter von Theodor von Taussig und Schwester der Malerin Helene von Taussig (1879–1942). Alice von Wassermann wurde – wie auch ihre Schwestern Clara von Hatvany-Deutsch und Helene von Taussig – Opfer des Holocaust. Leben Er absolvierte sein Medizinstudium von 1884 bis 1889 an den Universitäten Erlangen, Wien, München und Straßburg, wo er 1888 promoviert wurde. Nach seiner Approbation ging er 1890 als Volontär nach Berlin und trat 1891 in das neu gegründete Preußische Institut für Infektionskrankheiten ein, das von Robert Koch geleitet wurde und später als Robert-Koch-Institut für Infektionskrankheiten dessen Namen erhielt. Er wurde nach seiner Habilitation 1901 Assistenzarzt, dann Oberarzt und später – als Nachfolger Ludwig Briegers (1849–1919) – Leitender Arzt der Klinischen Abteilung des Instituts. 1902 war er zum Extraordinarius ernannt worden. Im Jahr 1906 übernahm er die Leitung der selbständigen Abteilung für experimentelle Therapie und Serumforschung. Im gleichen Jahr veröffentlichte er zusammen mit Albert Neisser und Carl Bruck die später nach ihm benannte Reaktion zur Serodiagnostik der Syphilis. Von 1913 bis zu seinem Tode war Wassermann Direktor des neu gegründeten Kaiser-Wilhelm- Instituts für experimentelle Therapie in Berlin-Dahlem. -

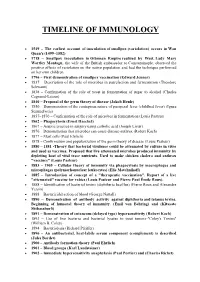

Timeline of Immunology

TIMELINE OF IMMUNOLOGY 1549 – The earliest account of inoculation of smallpox (variolation) occurs in Wan Quan's (1499–1582) 1718 – Smallpox inoculation in Ottoman Empire realized by West. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the wife of the British ambassador to Constantinople, observed the positive effects of variolation on the native population and had the technique performed on her own children. 1796 – First demonstration of smallpox vaccination (Edward Jenner) 1837 – Description of the role of microbes in putrefaction and fermentation (Theodore Schwann) 1838 – Confirmation of the role of yeast in fermentation of sugar to alcohol (Charles Cagniard-Latour) 1840 – Proposal of the germ theory of disease (Jakob Henle) 1850 – Demonstration of the contagious nature of puerperal fever (childbed fever) (Ignaz Semmelweis) 1857–1870 – Confirmation of the role of microbes in fermentation (Louis Pasteur) 1862 – Phagocytosis (Ernst Haeckel) 1867 – Aseptic practice in surgery using carbolic acid (Joseph Lister) 1876 – Demonstration that microbes can cause disease-anthrax (Robert Koch) 1877 – Mast cells (Paul Ehrlich) 1878 – Confirmation and popularization of the germ theory of disease (Louis Pasteur) 1880 – 1881 -Theory that bacterial virulence could be attenuated by culture in vitro and used as vaccines. Proposed that live attenuated microbes produced immunity by depleting host of vital trace nutrients. Used to make chicken cholera and anthrax "vaccines" (Louis Pasteur) 1883 – 1905 – Cellular theory of immunity via phagocytosis by macrophages and microphages (polymorhonuclear leukocytes) (Elie Metchnikoff) 1885 – Introduction of concept of a "therapeutic vaccination". Report of a live "attenuated" vaccine for rabies (Louis Pasteur and Pierre Paul Émile Roux). 1888 – Identification of bacterial toxins (diphtheria bacillus) (Pierre Roux and Alexandre Yersin) 1888 – Bactericidal action of blood (George Nuttall) 1890 – Demonstration of antibody activity against diphtheria and tetanus toxins. -

Albert Claude, 1899-1983 with the Determined Intent to Fmd out Whatever There Was in It in Terms of Isolatable from Christian De Duve and George E

~·~-------------------------NME~W~S~AMNO~V~IE;vW~S:---------------------------- Obituary 'microsomes'. That was the beginning of a rather long side voyage that led him into the heart of the cell, not in search of a virus, but Albert Claude, 1899-1983 with the determined intent to fmd out whatever there was in it in terms of isolatable from Christian de Duve and George E. Palade particles, and to account for them in a careful quantitative manner. It was a ALBERT CLAUDE, who died in Brussels on Having failed in his first project, Claude glorious voyage during which he worked out Sunday 22 May, belonged to that small group went on to study the fate of the mouse sar his now classic cell-fractionation procedure. of truly exceptional individuals who, drawing coma S-37 when grafted in rats. The thesis Most of what we know today about the almost exclusively on their own resources and he wrote on his observations earned him a chemistry and activities of subcellular com following a vision far ahead of their time, government scholarship which he used to ponents is based on his quantitative ap opened single-handedly an entirely new field go to Berlin. There he frrst worked at the proach. Claude enjoyed isolating whatever of scientific investigation. Cancer Institute of the University, but was was isolatable: from microsomes to 'large He was born on 23 August 1899, in forced to leave prematurely after showing granules' (later recognized as mitochondria), Longlier, a hamlet of some 800 inhabitants that the bacterial theory of cancer genesis chromatin threads and zymogen granules. -

Federation Member Society Nobel Laureates

FEDERATION MEMBER SOCIETY NOBEL LAUREATES For achievements in Chemistry, Physiology/Medicine, and PHysics. Award Winners announced annually in October. Awards presented on December 10th, the anniversary of Nobel’s death. (-H represents Honorary member, -R represents Retired member) # YEAR AWARD NAME AND SOCIETY DOB DECEASED 1 1904 PM Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (APS-H) 09/14/1849 02/27/1936 for work on the physiology of digestion, through which knowledge on vital aspects of the subject has been transformed and enlarged. 2 1912 PM Alexis Carrel (APS/ASIP) 06/28/1873 01/05/1944 for work on vascular suture and the transplantation of blood vessels and organs 3 1919 PM Jules Bordet (AAI-H) 06/13/1870 04/06/1961 for discoveries relating to immunity 4 1920 PM August Krogh (APS-H) 11/15/1874 09/13/1949 (Schack August Steenberger Krogh) for discovery of the capillary motor regulating mechanism 5 1922 PM A. V. Hill (APS-H) 09/26/1886 06/03/1977 Sir Archibald Vivial Hill for discovery relating to the production of heat in the muscle 6 1922 PM Otto Meyerhof (ASBMB) 04/12/1884 10/07/1951 (Otto Fritz Meyerhof) for discovery of the fixed relationship between the consumption of oxygen and the metabolism of lactic acid in the muscle 7 1923 PM Frederick Grant Banting (ASPET) 11/14/1891 02/21/1941 for the discovery of insulin 8 1923 PM John J.R. Macleod (APS) 09/08/1876 03/16/1935 (John James Richard Macleod) for the discovery of insulin 9 1926 C Theodor Svedberg (ASBMB-H) 08/30/1884 02/26/1971 for work on disperse systems 10 1930 PM Karl Landsteiner (ASIP/AAI) 06/14/1868 06/26/1943 for discovery of human blood groups 11 1931 PM Otto Heinrich Warburg (ASBMB-H) 10/08/1883 08/03/1970 for discovery of the nature and mode of action of the respiratory enzyme 12 1932 PM Lord Edgar D. -

Jules Bordet (1870-1961): Pioneer of Immunology

Singapore Med J 2013; 54(9): 475-476 M edicine in S tamps doi:10.11622/smedj.2013166 Jules Bordet (1870-1961): Pioneer of immunology Jonathan Dworkin1, MD, Siang Yong Tan2, MD, JD t the time when Jules Bordet began his ground- THE TRANSFORMATION OF IMMUNOLOGY breaking experiments at the Pasteur Institute, the field Bordet began work at the Pasteur Institute in 1894, and of immunology was shrouded in pseudoscientific despite being part of Metchnikoff’s lab, he was more interested uncertainty. The lifting of this veil, through the in studying serum than white cells. The arrangement was Apersistent and patient process of experimentation, was Bordet’s an awkward one in which Bordet was compelled to put into great contribution to medicine in the 20th century. writing his research findings regarding the role of phagocytes, although in reality, his work had little to do with phagocytosis. BACKGROUND Jules Bordet was born in 1870 in Bordet possessed a reserved temperament and shunned the Soignies, a small town in Belgium. In 1874, his family moved to cult of personality that then existed around the brilliant but Brussels, and he attended a primary school in the Ecole unstable Metchnikoff. Given the contrast with his fiery Russian Moyenne, where his father taught. In secondary school, Bordet mentor, it was no surprise that Bordet evolved into a careful became interested in chemistry, and at the age of sixteen, he scientist, skeptical of broad principles derived from scant enrolled into medical school at the Free University of Brussels. data and content to draw conclusions on as narrow a basis as His early promise as a researcher earned him a scholarship the facts supported. -

Nobel Laureates in Physiology Or Medicine

All Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine 1901 Emil A. von Behring Germany ”for his work on serum therapy, especially its application against diphtheria, by which he has opened a new road in the domain of medical science and thereby placed in the hands of the physician a victorious weapon against illness and deaths” 1902 Sir Ronald Ross Great Britain ”for his work on malaria, by which he has shown how it enters the organism and thereby has laid the foundation for successful research on this disease and methods of combating it” 1903 Niels R. Finsen Denmark ”in recognition of his contribution to the treatment of diseases, especially lupus vulgaris, with concentrated light radiation, whereby he has opened a new avenue for medical science” 1904 Ivan P. Pavlov Russia ”in recognition of his work on the physiology of digestion, through which knowledge on vital aspects of the subject has been transformed and enlarged” 1905 Robert Koch Germany ”for his investigations and discoveries in relation to tuberculosis” 1906 Camillo Golgi Italy "in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system" Santiago Ramon y Cajal Spain 1907 Charles L. A. Laveran France "in recognition of his work on the role played by protozoa in causing diseases" 1908 Paul Ehrlich Germany "in recognition of their work on immunity" Elie Metchniko France 1909 Emil Theodor Kocher Switzerland "for his work on the physiology, pathology and surgery of the thyroid gland" 1910 Albrecht Kossel Germany "in recognition of the contributions to our knowledge of cell chemistry made through his work on proteins, including the nucleic substances" 1911 Allvar Gullstrand Sweden "for his work on the dioptrics of the eye" 1912 Alexis Carrel France "in recognition of his work on vascular suture and the transplantation of blood vessels and organs" 1913 Charles R. -

Elie Metchnikoff – Founder of Longevity Science – 2015

ISSN 20790570, Advances in Gerontology, 2015, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 201–208. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2015. Published in Russian in Uspekhi Gerontologii, 2015, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 207–217. Elie Metchnikoff—The Founder of Longevity Science and a Founder of Modern Medicine: In Honor of the 170th Anniversary1 Ilia Stambler Department of Science, Technology and Society, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel email: [email protected] Abstract—The years 2015–2016 mark a double anniversary—the 170th anniversary of birth and the 100th anni versary of death—of one of the greatest Russian scientists, a person that may be considered a founding figure of modern immunology, aging, and longevity science—Elie Metchnikoff (May 15, 1845–July 15, 1916). At this time of rapid aging of the world population and the rapid development of technologies that may amelio rate degenerative aging processes, Metchnikoff’s pioneering contribution to the search for antiaging and healthspanextending means should be recalled and honored. Keywords: Elie Metchnikoff, medical history, aging and longevity research DOI: 10.1134/S2079057015040219 ELIE1 METCHNIKOFF—THE FOUNDER OF GERONTOLOGY The world is rapidly aging, threatening grave con sequences for the global society and economy, while the rapid development of biomedical science and technology stand as the first line of defense against the potential threat. These two everincreasing forces bring gerontology, which describes the challenges of aging while at the same time seeking means to address those challenges, to the center stage of the global sci entific, technological, and political discourse. At this time, it may be fit to honor the persons who stood at the origin of gerontological discourse, not just as a sci entific field but as a social and intellectual movement.