Kosovo by Krenar Gashi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dayton Accords and the Escalating Tensions in Kosovo

Berkeley Undergraduate Journal 68 THE DAYTON ACCORDS AND THE ESCALATING TENSIONS IN KOSOVO By Christopher Carson Abstract his paper argues that the Dayton Accords, which ended the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, were the primary cause of the outbreak of violence in Kosovo in 1998. While the Accords were regarded as successful in neighboring Bosnia, the agreement failed to mention the Texisting situation in Kosovo, thus perpetuating the ethnic tensions within the region. Following the Dayton Accords, the response by the international community failed to address many concerns of the ethnically Albanian population living in Kosovo, creating a feeling of alienation from the international political scene. Finally, the Dayton Accords indirectly contributed to the collapse of the Albanian government in 1997, creating a shift in the structure of power in the region. This destabilization triggered the outbreak of war between Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo the following year. The Dayton Accords 69 I. Introduction For many years, the territory of Kosovo functioned as an autonomous region within the state of Yugoslavia. During that time, Kosovo was the only Albanian-speaking territory within Yugoslavia, having been home to a significant Albanian population since its creation. The region also had a very important meaning for the Serb community, as it was the site of the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, which defined Serbian nationalism when Serbian forces were defeated by the Ottoman Empire. In the 1980s, tensions began to arise between the two communities, initially resulting in protests against the centralized government in Belgrade and arrests of Albanian Kosovars. Under the presidency of Slobodan Milošević, these ethnic tensions intensified both in Kosovo and elsewhere in Yugoslavia. -

Toponyms of Albania As Personal Names Among Kosovo Albanians

Toponyms of Albania as personal names among Kosovo Albanians Bardh Rugova University of Prishtina, Kosovo Toponyms of Albania as personal names among Kosovo Albanians Abstract: This paper aims at analyzing the trend among Kosovo Albanians to create given names using toponyms of Albania in various social and political circumstances. The research is conducted from a sociolinguistic perspective. During the years of non-communication between Albania and Yugoslavia, Albanians in Kosovo have expressed their Albanian identity by naming their children using names of towns, provinces, islands and rivers from Albania. Data taken from birth registrars’ offices through the years show the Kosovar Albanians’ point of view towards the state of Albania. It reflects the symbolic role that Albania had/ has for Albanians beyond its geographical borders. Keywords: given names, identity, sociolinguistics, toponyms. This paper aims at analyzing the trend among Kosovo Albanians to give names to children using toponyms of Albania in various social and political circumstances. The research is conducted from the sociolinguistic perspective. During the years of severance of relations between Albania and Yugoslavia, Albanians in Yugoslavia, most of whom were inhabitants of Kosovo, have expressed their Albanian identity, inter alia, also by naming their children using town names of Albania (Vlora, Elbasan, Berat, Milot, Saranda), province names (Mirdita, Mat), river names (Drin, Drilon, Vjosa, Shkumbin, Erzen), island names (Sazan), the names of the two seas (Adriatic and Jon), and a mountain name (Tomor). The trend of giving such names reflects also the social context of Kosovo Albanians. In Albania1 such names have not been given at all, with few exceptions. -

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order Online

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order online Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Glossary 1. Executive Summary The 1999 Offensive The Chain of Command The War Crimes Tribunal Abuses by the KLA Role of the International Community 2. Background Introduction Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Kosovo in the 1990s The 1998 Armed Conflict Conclusion 3. Forces of the Conflict Forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Yugoslav Army Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs Paramilitaries Chain of Command and Superior Responsibility Stucture and Strategy of the KLA Appendix: Post-War Promotions of Serbian Police and Yugoslav Army Members 4. march–june 1999: An Overview The Geography of Abuses The Killings Death Toll,the Missing and Body Removal Targeted Killings Rape and Sexual Assault Forced Expulsions Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions Destruction of Civilian Property and Mosques Contamination of Water Wells Robbery and Extortion Detentions and Compulsory Labor 1 Human Shields Landmines 5. Drenica Region Izbica Rezala Poklek Staro Cikatovo The April 30 Offensive Vrbovac Stutica Baks The Cirez Mosque The Shavarina Mine Detention and Interrogation in Glogovac Detention and Compusory Labor Glogovac Town Killing of Civilians Detention and Abuse Forced Expulsion 6. Djakovica Municipality Djakovica City Phase One—March 24 to April 2 Phase Two—March 7 to March 13 The Withdrawal Meja Motives: Five Policeman Killed Perpetrators Korenica 7. Istok Municipality Dubrava Prison The Prison The NATO Bombing The Massacre The Exhumations Perpetrators 8. Lipljan Municipality Slovinje Perpetrators 9. Orahovac Municipality Pusto Selo 10. Pec Municipality Pec City The “Cleansing” Looting and Burning A Final Killing Rape Cuska Background The Killings The Attacks in Pavljan and Zahac The Perpetrators Ljubenic 11. -

Statement by Herman Van Rompuy President of the European Council Following His Meeting with Atifete Jahjaga President of Kosovo

EUROPEAN COUNCIL THE PRESIDENT EN Brussels, 6 September 2011 EUCO 66/11 PRESSE 298 PR PCE 39 Statement by Herman Van Rompuy President of the European Council following his meeting with Atifete Jahjaga President of Kosovo I am pleased to welcome President Jahjaga in Brussels today. Her visit takes place only a few days after the latest round of the Pristina - Belgrade dialogue, so allow me to start on that topic. Let me emphasise that the EU is very satisfied with the latest agreements on Customs Stamps and Cadastre. The agreements reached last Friday are truly European solutions to some very difficult issues. In particular, the agreement on customs stamps is crucial, since it will result in the lifting of the mutual trade embargoes. This is a significant step in improving relations in the region and ensuring freedom of movement of goods in accordance with European values and standards. However, there is more to do. Discussions need to continue and further progress needs to be made on the remaining issues. We need to find equally creative and pragmatic solutions for the issues of telecommunication, energy, and representation in regional fora. Dialogue, compromise and consensus seeking are the European way. Both sides have everything to gain from these deals, as the aim of this dialogue is to bring both sides closer to the EU, to improve mutual cooperation, and to improve the lives of ordinary people. This brings me to the other topic of our discussion today, namely the relations between the European Union and Kosovo, and related developments in Kosovo itself. -

Expressing Politeness and Politeness Strategies in Spoken Albanian Konuşulan Arnavutçada Nezaket Ve Nezaket Stratejileri

Doi Number :http://dx.doi.org/10.12981/motif.432 Orcid ID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3047-1500 Orcid ID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5346-3186 Motif Akademi Halkbilimi Dergisi, 2018, Cilt: 11, Sayı: 21, 78-86. EXPRESSING POLITENESS AND POLITENESS STRATEGIES IN SPOKEN ALBANIAN ♦ KONUŞULAN ARNAVUTÇADA NEZAKET VE NEZAKET STRATEJİLERİNİ İFADE ETME Bardh RUGOVA* Lindita SEJDIU RUGOVA** ABSTRACT: The present study aims at treating the linguistic devices of politeness in the spoken formal and informal communication of Albanians of Kosovo and Albania as one of the variables that display the changes in the dynamics of Albanian spoken in the two countries. The current research treats formal situations of communication and those less formal ones of linguistic devices of politeness. The research has been conducted using two different measurement. The first one treats two television political debates, one in Kosovo with Kosovar speakers of Albanian, and one in Albania with Albanian speakers. The second measuring treats the informal situation, and for this purpose, a direct observation in the “Albi Mall” (a city mall), specifically in five stores (shoe store, clothing store, and grocery store) in Prishtina has been conducted. In this research, linguistic choices used by the consumers who address the sellers and sellers who address the consumers have been observed. Keywords: Politeness, strategies, formulaic expressions. ÖZ: Bu çalışmanın amacı, iki ülkede konuşulan Arnavutça dinamiklerindeki değişimleri gösteren değişkenlerden biri olarak Kosova ve Arnavutluk Arnavutlarının sözlü resmî ve gayriresmî iletişimde sözlü dil bilgisi araçlarını ele almaktır. Araştırma, resmî iletişim durumlarını ve nazik dilsel araçlardan daha az resmî olanları ele almaktadır. Araştırma iki farklı ölçme kullanılarak gerçekleştirildi. -

Politiska Partier I Europa

STVA22: Statsvetenskap fortsättningskurs, delkurs: Hur stater styrs VT 2013 Politiska partier i Europa En jämförelse mellan finska Sannfinländarna och kosovoalbanska Lëvizja Vetëvendosje Algot Pihlström & Berat Meholli Lunds universitet 2013-05-21 Meholli & Pihlström Sannfinländarna & Lëvizja Vetëvendosje Lunds universitet 2013-05-21 Abstract With the current political climate in Europe and certain European countries as a background our essay compares the Finnish Sannfinländarna and Kosovo-Albanian Lëvizja Vetëvendosje. The aim of this essay is to examine whether similarities between these political parties exists or not. Political programs related to the Finnish and Kosovo- Albanian party is the essay´s empirical data and foundation. Our essay is conducted as a case study research where the empirical data is analysed on the basis of a theoretical framework about the classification of political parties. The analysis indicates that there are similarities between these political parties and that these similarities can also be considered as differences because their articulation (and context) varies. The analysis indicates also that Sannfinländarna and Lëvizja Vetëvendosje are to be considered as centre parties where the difference between them is insignificant. 2 Meholli & Pihlström Sannfinländarna & Lëvizja Vetëvendosje Lunds universitet 2013-05-21 Innehållsförteckning Disposition .................................................................................................................................. 4 Kapitel 1 .................................................................................................................................... -

Kosovo's New Political Leadership

ASSEMBLY SUPPORT INITIATIVE asiNEWSLETTER Kosovo’s new political leadership ASSEMBLYasi SUPPORT INITIATIVE NEWSLETTER юѦȱŘŖŖŜǰȱќȱŘŘ Strengthening the oversight role of the Kosovo Assembly oces Mission in Kosovo ASSEMBLY SUPPORT INITIATIVE 2 NEWSLETTERasi Editorial Editorial 2 Kosovo has a new political leadership. Within one Mr. Kolë Berisha’s speech on the occasion ǰȱȱ ȱǰȱ ȱȱȱȱ of assuming the Assembly Presidency 3 ȱȱȱȱ¢ȱȱĜǯȱȱ Fatmir Sejdiu succeeded the late President Ibrahim President Fatmir Sejdiu talks to BBC 6 Rugova. Former TMK Commander Agim Ceku succeeded Bajram Kosumi as prime minister. Mr. “There is no full freedom in Kosovo Kole Berisha succeeded Nexhat Daci as president unless all of Kosovo’s citizens can enjoy it” 7 ȱȱ¢ǯȱ¢ǰȱȱ ȱȱȱȱȱ ȱȱ ȱǯȱȱŘŚȱȱŘŖŖŜǰȱȱ¢ȱȱ Kosovo Serb Leaders Meet Premier Çeku, ȱ¡ȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱęȱ ȱ Consider Joining Government 9 rounds of talks on decentralization. Recent Developments in the Assembly 10 ȱȱȱȱȱȱȱĴȱȱȱȱ¢ȱ sessions in the Assembly on various policy issues. The new president Let’s learn to hear the voice of the citizen 12 ȱȱ¢ǰȱǯȱ ȱǰȱȱȱȱȱȱ¢ȱ a new democratic atmosphere and to strengthen co-operation with Presidency of the Assembly 14 international institutions. Transparency and full adherence to Rules Why we asked for a new dynamic in of Procedure are high on his agenda. Assembly’s Work 16 In light of the current changes at the Assembly one can hope that this ȱǰȱȱȱȱ¢ȱȱȱĴǰȱ Our Vision of an Independent Kosovo 17 to further enhance their role in overseeing the work of the government ȱ ¡ȱ ęȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ Pay off Time 18 Consolidated Budget (KCB). -

PUBLIC Date Original: 26/10/2020 19:18:00 Date Corrected Version: 28/10/2020 14:39:00 Date Public Redacted Version: 05/11/2020 16:53:00

KSC-BC-2020-06/F00027/A08/COR/RED/1 of 5 PUBLIC Date original: 26/10/2020 19:18:00 Date corrected version: 28/10/2020 14:39:00 Date public redacted version: 05/11/2020 16:53:00 In: KSC-BC-2020-06 Before: Pre-Trial Judge Judge Nicolas Guillou Registrar: Dr Fidelma Donlon Date: 26 October 2020 Language: English Classification: Public Public Redacted Version of Corrected Version of Order for Transfer to Detention Facilities of the Specialist Chambers Specialist Prosecutor Defence for Jakup Krasniqi Jack Smith To be served on Jakup Krasniqi KSC-BC-2020-06/F00027/A08/COR/RED/2 of 5 PUBLIC Date original: 26/10/2020 19:18:00 Date corrected version: 28/10/2020 14:39:00 Date public redacted version: 05/11/2020 16:53:00 I, JUDGE NICOLAS GUILLOU, Pre-Trial Judge of the Kosovo Specialist Chambers, assigned by the President of the Specialist Chambers pursuant to Article 33(1)(a) of Law No. 05/L-53 on Specialist Chambers and Specialist Prosecutor’s Office (“Law”); BEING SEISED of the strictly confidential and ex parte “Submission of Indictment for Confirmation”, dated 24 April 2020, “Request for Arrest Warrants and Related Orders”, dated 28 May 2020, and “Submission of Revised Indictment for Confirmation”, dated 24 July 2020, of the Specialist Prosecutor’s Office (“SPO”); HAVING CONFIRMED, in the “Decision on the Confirmation of the Indictment Against Hashim Thaçi, Kadri Veseli, Rexhep Selimi and Jakup Krasniqi”, dated 26 October 2020, the Revised Indictment (“Confirmed Indictment”) and having found therein that there is a well-grounded suspicion that -

Downloaded 4.0 License

Security and Human Rights (2020) 1-5 Book Review ∵ Daan W. Everts (with a foreword by Jaap de Hoop Scheffer), Peacekeeping in Albania and Kosovo; Conflict response and international intervention in the Western Balkans, 1997 – 2002 (I.B.Tauris, July 2020), 228p. £. 13,99 paperback Fortunately, at the international scene there are those characters who venture into complex crises and relentlessly work for their solution. Sergio Viero de Melo seems to be their icon. Certainly, Daan Everts, the author of Peacekeeping in Albania and Kosovo belongs to this exceptional group of pragmatic crisis managers in the field. Between 1997 and 2002 he was the osce’s represent- ative in crisis-hit Albania and Kosovo. Now, twenty years later, Mr Everts has published his experiences, and luckily so; the book is rich in content and style, and should become obligatory reading for prospective diplomats and military officers; and it certainly is interesting material for veterans of all sorts. Everts presents the vicissitudes of his life in Tirana and Pristina against the background of adequate introductions to Albanian and Kosovar history, which offer no new insights or facts. All in all, the book is a sublime primary source of diplomatic practice. The largest, and clearly more interesting part of the book is devoted to the intervention in Kosovo. As a matter of fact, the 1999 war in Kosovo deepened ethnic tensions in the territory. Therefore, the author says, the mission in Kosovo was highly complex, also because the mandate was ambivalent with regard to Kosovo’s final status. Furthermore, the international community (Everts clearly does not like that term) for the time being had to govern Kosovo as a protectorate. -

Report Between the President and Constitutional Court and Its Influence on the Functioning of the Constitutional System in Kosovo Msc

Report between the President and Constitutional Court and its influence on the functioning of the Constitutional System in Kosovo MSc. Florent Muçaj, PhD Candidate Faculty of Law, University of Prishtina, Kosovo MSc. Luz Balaj, PhD Candidate Faculty of Law, University of Prishtina, Kosovo Abstract This paper aims at clarifying the report between the President and the Constitutional Court. If we take as a starting point the constitutional mandate of these two institutions it follows that their final mission is the same, i.e., the protection and safeguarding of the constitutional system. This paper, thus, will clarify the key points in which this report is expressed. Further, this paper examines the theoretical aspects of the report between the President and the Constitutional Court, starting from the debate over this issue between Karl Schmitt and Hans Kelsen. An important part of the paper will examine the Constitution of Kosovo, i.e., the contents of the constitutional norm and its application. The analysis focuses on the role such report between the two institutions has on the functioning of the constitutional system. In analyzing the case of Kosovo, this paper examines Constitutional Court cases in which the report between the President and the Constitutional Court has been an issue of review. Such cases assist us in clarifying the main theme of this paper. Therefore, the reader will be able to understand the key elements of the report between the President as a representative of the unity of the people on the one hand and the Constitutional Court as a guarantor of constitutionality on the other hand. -

Introduction

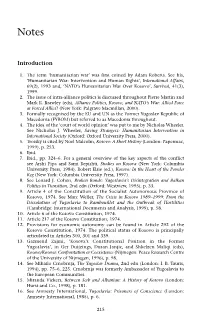

Notes Introduction 1. The term ‘humanitarian war’ was first coined by Adam Roberts. See his, ‘Humanitarian War: Intervention and Human Rights’, International Affairs, 69(2), 1993 and, ‘NATO’s Humanitarian War Over Kosovo’, Survival, 41(3), 1999. 2. The issue of intra-alliance politics is discussed throughout Pierre Martin and Mark R. Brawley (eds), Alliance Politics, Kosovo, and NATO’s War: Allied Force or Forced Allies? (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000). 3. Formally recognised by the EU and UN as the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) but referred to as Macedonia throughout. 4. The idea of the ‘court of world opinion’ was put to me by Nicholas Wheeler. See Nicholas J. Wheeler, Saving Strangers: Humanitarian Intervention in International Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). 5. Trotsky is cited by Noel Malcolm, Kosovo: A Short History (London: Papermac, 1999), p. 253. 6. Ibid. 7. Ibid., pp. 324–6. For a general overview of the key aspects of the conflict see Arshi Pipa and Sami Repishti, Studies on Kosova (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), Robert Elsie (ed.), Kosovo: In the Heart of the Powder Keg (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997). 8. See Lenard J. Cohen, Broken Bonds: Yugoslavia’s Disintegration and Balkan Politics in Transition, 2nd edn (Oxford: Westview, 1995), p. 33. 9. Article 4 of the Constitution of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, 1974. See Marc Weller, The Crisis in Kosovo 1989–1999: From the Dissolution of Yugoslavia to Rambouillet and the Outbreak of Hostilities (Cambridge: International Documents and Analysis, 1999), p. 58. 10. Article 6 of the Kosovo Constitution, 1974. -

The Letter of Support to the Initiative For

President of Kosovo, Mrs. Atifete Jahjaga Member of Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mr. Bakir Izetbegovic President of Serbia, Mr. Boris Tadic President of Slovenia, Mr. Danilo Turk President of Macedonia, Mr. Djordje Ivanov President of Montenegro, Mr. Filip Vujanovic President of Croatia, Mr. Ivo Josipovic Member of Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mr. Nebojsa Radmanovic Member of Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mr. Zeljko Komsic Subject: Establishment of RECOM Sarajevo, Belgrade, Prishtina, Zagreb, Skopje, Podgorica, Ljubljana October 2011 Your Excellencies, Presidents and Members of Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, We believe that citizens of the countries of the former Yugoslavia have a need and the right to know all the facts about war crimes and other massive human rights violations committed during the wars of the 1990s. They also have the right and a need, we believe, to know the consequences of those wars. This is why we are writing to you. For over a decade, since the weapons have been muted, post-Yugoslav societies have not been able to cope with the heavy legacy of the war past, largely because the fate of a number of those killed, forcibly disappeared, tortured, and persecuted – the people who suffered in so many different, horrible ways – remains unknown to date. Only a few names of those who died are known, but more than 13,000 families of forcibly disappeared persons are still searching for their loved ones. On top of this, there is no organized, systematic mechanism for the victims to seek and obtain fair reparation; and the lack of reliable facts about the victims is continually used for political manipulation, nationalist promotion, hatred and intolerance.