Dress Codes and School Uniforms in Victorian Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Cunning Isobel Meets Nanny”

© 2015 Angela M. Bauer All Rights Reserved Isobel Chapter 3 “Cunning Isobel Meets Nanny” Fiction by Angela Bauer Once Valery and Isobel were towel-dried after their Sunday night bath, their mommy Sylvia had them sit on their potties. Isobel produced nothing, but Valery managed to void a significant amount of pee and a moderate-size soft stool. They were wiped, diapered, given pacifiers and tucked into their cribs. During the night Sylvia checked and found Isobel’s diaper was nearly saturated, so she changed her older daughter. Then she decided to prophylactically change Valery’s diaper. Monday morning she let her girls sleep late in the nursery. Shortly before 8:00 A.M. she carried Valery and led Isobel downstairs while they were still wearing their night diapers and Onesies. She had just buckled the girls into their highchairs when the tallish and beautiful twenty-six year-old Nanny Carmen arrived. Sylvia had a bowl of the Pablum/Metamucil mixture in each hand. Hurriedly she put those on the respective highchair trays so she could properly greet Nanny Carmen. What impressed Carmen was that without fuss the smaller Valery picked up her own spoon and began eating her mixture. The far larger Isobel stared at her. After an exchange of greetings Sylvia hurried to bring Valery a Sippy cup of milk and a baby bottle of milk to Isobel. Only after holding that so Isobel could eagerly suckle a couple of ounces of milk did her mother begin to spoon-feed her the mixture. Page 1 © 2015 Angela M. -

A Blitz on Bugs in the Bedding

THE MAGAZINE OF THE INSTITUTE OF CONSERVATION • SEPTEMBER 2011 • ISSUE 36 A blitz on bugs in the bedding Also in this issue PACR news and the new Conservation Register Showcasing intern work in Ireland A 16th century clock WILLARD CONSERVATION EQUIPMENT visit us online at www.willard.co.uk Willard Conservation manufactures and supplies a unique range of conservation tools and equipment, specifically designed for use in the conservation and preservation of works of art and historic cultural media. Our product range provides a premier equipment and technology choice at an affordable price. Visit our website at www.willard.co.uk to see our wide range of conservation equipment and tools and to find out how we may be able to help you with your specific conservation needs. Willard Conservation Limited By Appointment To Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II Leigh Road, Terminus Industrial Estate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8TS Conservation Equipment Engineers Willard Conservation Ltd, T: +44 (0)1243 776928 E: [email protected] W: www.willard.co.uk Chichester 2 inside SEPTEMBER 2011 Issue 36 It is an autumn of welcomes. 2 NEWS First, welcome to the new version of the Conservation Interesting blogs and Register which went live at the end of August. Do take a look websites , research projects, at it at www.conservationregister.com and help with putting uses for a municipal sculpture right any last minute glitches by filling in the feedback survey and a new bus shelter form. 7 Welcome, too, to the latest batch of Accredited members. 4 PROFESSIONAL UPDATE Becoming accredited and then sustaining your professional Notice of Board Elections and credentials is no walk in the park, so congratulations for the next AGM, PACR updates, completing the first stage and good luck in your future role as training and library news the profession’s exemplars and ambassadors. -

“The Answer to Laundry in Outer Space”: the Rise and Fall of The

Archived thesis/research paper/faculty publication from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ University of North Carolina Asheville “The Answer to Laundry in Outer Space”: The Rise and Fall of the Paper Dress in 1960s American Fashion A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History In Candidacy for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History By Virginia Knight Asheville, North Carolina November 2014 1 A woman stands in front of a mirror in a dressing room, a sales assistant by her side. The sales assistant, with arms full of clothing and a tape measure around her neck, beams at the woman, who is looking at her reflection with a confused stare. The woman is wearing what from the front appears to be a normal, knee-length floral dress. However, the mirror behind her reveals that the “dress” is actually a flimsy sheet of paper that is taped onto the woman and leaves her back-half exposed. The caption reads: “So these are the disposable paper dresses I’ve been reading about?” This newspaper cartoon pokes fun at one of the most defining fashion trends in American history: the paper dress of the late 1960s.1 In 1966, the American Scott Paper Company created a marketing campaign where customers sent in a coupon and shipping money to receive a dress made of a cellulose material called “Dura-Weave.” The coupon came with paper towels, and what began as a way to market Scott’s paper products became a unique trend of American fashion in the late 1960s. -

Narration on Ethnic Jewellery of Kerala-Focusing on Design, Inspiration and Morphology of Motifs

Journal of Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology Review Article Open Access Narration on ethnic jewellery of Kerala-focusing on design, inspiration and morphology of motifs Abstract Volume 6 Issue 6 - 2020 Artefacts in the form of Jewellery reflect the essence of the lifestyle of the people who Wendy Yothers,1 Resmi Gangadharan2 create and wear them, both in the historic past and in the living present. They act as the 1Department of Jewellery Design, Fashion Institute of connecting link between our ancestors, our traditions, and our history. Jewellery is used- Technology, USA -both in the past and the present-- to express the social status of the wearer, to mark 2School of Architecture and Planning, Manipal Academy of tribal identity, and to serve as amulets for protection from harm. This paper portrays the Higher Education, Karnataka, India ethnic ornaments of Kerala with insights gained from examples of Jewellery conserved in the Hill Palace Museum and Kerala Folklore Museum, in Cochin, Kerala. Included are Correspondence: Wendy Yothers, Department of Jewellery Thurai Balibandham, Gaurisankara Mala, Veera Srunkhala, Oddyanam, Bead necklaces, Design, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, USA, Nagapadathali and Temple Jewellery. Whenever possible, traditional Jewellery is compared Email with modern examples to illustrate how--though streamlined, traditional designs are still a living element in the Jewellery of Kerala today. Received: October 17, 2020 | Published: December 14, 2020 Keywords: ethnic ornaments, Kerala jewellery, sarpesh, gowrishankara mala, veera srunkhala Introduction Indian cultures have used Jewellery as a strong medium to reflect their rituals. The design motifs depicted on the ornaments of India Every artifact has a story to tell. -

Line Count/Costumes PDF Click Here to View

Character information for ______________________________________________________________ NB – for larger schools, extra speaking characters can easily be added to scenes and the existing lines shared out between them. Equally, for smaller schools, because many characters only appear in one scene, multiple parts can be played by a single actors. ______________________________________________________________ 37 speaking characters order of appearance. ______________________________________________________________ * A ‘line’ is defined as each time a character speaks - usually between one and five actual lines of text each time. Number of Speaking Character spoken lines * Costume Suggestions Rudolph 13 A red nose, a reindeer ‘onesie’ or brown top, leggings and antlers. Gabriel 14 Traditional nativity angel costume, with wings and halo. Charles Dickens 10 Victorian look – bow-tie, waistcoat and jacket. Long goatee beard. Erika Winterbörn 9 Viking tunic and helmet. Fur shawl or wrap. Festivius Maximus 10 Roman toga, laurel crown and red cloak. Senilius 11 Roman toga and red cloak. White beard. Tipsius 6 Plain brown or grey tunic, belted. Violentia 2 Armour breast plate over a white tunic, greaves and a helmet. Bratius 2 Plain brown or grey tunic, belted. Moodica 2 Plain brown or grey tunic, belted. Lavatoria 1 Long, belted elegant dress, tiara and jewellery. Olaf 6 Viking tunic and helmet. Fur shawl or wrap. Astrid 5 Viking tunic and helmet. Fur shawl or wrap. Hair in plaits. Cow 1 1 Cow ‘onesie’ or brown/black & white, leggings and a mask or horns. Cow 2 1 Cow ‘onesie’ or brown/black & white, leggings and a mask or horns. Cow 3 1 Cow ‘onesie’ or brown/black & white, leggings and a mask or horns. -

Use and Applications of Draping in Turkey's

USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION DUYGU KOCABA Ş MAY 2010 USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF IZMIR UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS BY DUYGU KOCABA Ş IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENTOF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DESIGN IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MAY 2010 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Cengiz Erol Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Prof. Dr. Tevfik Balcıoglu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adaquate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Design. ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz Supervisor Examining Committee Members Asst. Prof. Dr. Duygu Ebru Öngen Corsini ..................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Nevbahar Göksel ...................................................... Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen Kipöz ...................................................... ii ABSTRACT USE AND APPLICATIONS OF DRAPING IN TURKEY’S CONTEMPORARY FASHION Kocaba ş, Duygu MDes, Department of Design Studies Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Şölen K İPÖZ May 2010, 157 pages This study includes the investigations of the methodology and applications of draping technique which helps to add creativity and originality with the effects of experimental process during the application. Drapes which have been used in different forms and purposes from past to present are described as an interaction between art and fashion. Drapes which had decorated the sculptures of many sculptors in ancient times and the paintings of many artists in Renaissance period, has been used as draping technique for fashion design with the contributions of Madeleine Vionnet in 20 th century. -

Where We Are in Place and Time – 1St Oct 2019 Save Nature

Where we are in place and time – 1st Oct 2019 Save Nature – 3rd Oct 2019 Magazine by Ajooni Kaur – 3rd Oct 2019 Learn & Play – Kindergarten 4th October 4, 2019 A Step Towards Global Warming – Myp 2 & 3 Differences in Kinetic and Potential Energy – PYP 1 & 3 – 9th Oct 2019 ART FORMS-Song composition by students – 10th Oct 2019 Learning is Fun – PYP 4 – 10th Oct 2019 MUN training Session – 10th Oct 2019 Sorting the basket: Kindergarten Activity – 14th Oct 2019 Travel and Origin – PYP 3 – 15th Oct 2019 Landforms – PYP 1 – 15th Oct 2019 Egmore Museum Field Trip (MYP1 to DP1) – 16th Oct 2019 Eldrok Awards – 16th Oct 2019 Save Nature - An Awareness Program – 16th Oct 2019 Element Card Games – 16th Oct 2019 Class Debate-”Performance Art vs Visual Art -PYP 5 – 17th Oct 2019 ART FORM-WALL MURAL – 17th Oct 2019 Seminar of Population – 18th Oct 2019 Cookery Club – 18th Oct 2019 Skype Meeting – 18th Oct 2019 Waldrof Teaching Methodology – 19th Oct 2019 Kindergarten Activities – 21st Oct 2019 Grammar and Vocabulary – 22nd Oct 2019 Effervescence – Kindergarten – 22nd Oct 2019 Types of Soil – PYP 4 – 24th Oct 2019 TOK – 24th Oct 2019 Presentation On Extended Essay – Oct 24th A live demonstration by fire fighters – Oct 25th Exploration and Observation by PYP – 29th Oct 2019 Where we are in place and time – 1st Oct 2019 The learners of PYP 1, 2 and 3 started with their 2nd unit "Where we are in place and time.” Each grade has started exploring this as per their understanding. PYP 1 explored the concept of rotation and revolution, the different seasons, and the changes that occur with the seasons. -

The Morgue File 2010

the morgue file 2010 DONE BY: ASSIL DIAB 1850 1900 1850 to 1900 was known as the Victorian Era. Early 1850 bodices had a Basque opening over a che- misette, the bodice continued to be very close fitting, the waist sharp and the shoulder less slanted, during the 1850s to 1866. During the 1850s the dresses were cut without a waist seam and during the 1860s the round waist was raised to some extent. The decade of the 1870s is one of the most intricate era of women’s fashion. The style of the early 1870s relied on the renewal of the polonaise, strained on the back, gath- ered and puffed up into an detailed arrangement at the rear, above a sustaining bustle, to somewhat broaden at the wrist. The underskirt, trimmed with pleated fragments, inserting ribbon bands. An abundance of puffs, borders, rib- bons, drapes, and an outlandish mixture of fabric and colors besieged the past proposal for minimalism and looseness. women’s daywear Victorian women received their first corset at the age of 3. A typical Victorian Silhouette consisted of a two piece dress with bodice & skirt, a high neckline, armholes cut under high arm, full sleeves, small waist (17 inch waist), full skirt with petticoats and crinoline, and a floor length skirt. 1894/1896 Walking Suit the essential “tailor suit” for the active and energetic Victorian woman, The jacket and bodice are one piece, but provide the look of two separate pieces. 1859 zouave jacket Zouave jacket is a collarless, waist length braid trimmed bolero style jacket with three quarter length sleeves. -

JEWELLERY TREND REPORT 3 2 NDCJEWELLERY TREND REPORT 2021 Natural Diamonds Are Everlasting

TREND REPORT ew l y 2021 STATEMENT J CUFFS SHOULDER DUSTERS GENDERFLUID JEWELLERY GEOMETRIC DESIGNS PRESENTED BY THE NEW HEIRLOOM CONTENTS 2 THE STYLE COLLECTIVE 4 INDUSTRY OVERVIEW 8 STATEMENT CUFFS IN AN UNPREDICTABLE YEAR, we all learnt to 12 LARGER THAN LIFE fi nd our peace. We seek happiness in the little By Anaita Shroff Adajania things, embark upon meaningful journeys, and hold hope for a sense of stability. This 16 SHOULDER DUSTERS is also why we gravitate towards natural diamonds–strong and enduring, they give us 20 THE STONE AGE reason to celebrate, and allow us to express our love and affection. Mostly, though, they By Sarah Royce-Greensill offer inspiration. 22 GENDERFLUID JEWELLERY Our fi rst-ever Trend Report showcases natural diamonds like you have never seen 26 HIS & HERS before. Yet, they continue to retain their inherent value and appeal, one that ensures By Bibhu Mohapatra they stay relevant for future generations. We put together a Style Collective and had 28 GEOMETRIC DESIGNS numerous conversations—with nuance and perspective, these freewheeling discussions with eight tastemakers made way for the defi nitive jewellery 32 SHAPESHIFTER trends for 2021. That they range from statement cuffs to geometric designs By Katerina Perez only illustrates the versatility of their central stone, the diamond. Natural diamonds have always been at the forefront of fashion, symbolic of 36 THE NEW HEIRLOOM timelessness and emotion. Whether worn as an accessory or an ally, diamonds not only impress but express how we feel and who we are. This report is a 41 THE PRIDE OF BARODA product of love and labour, and I hope it inspires you to wear your personality, By HH Maharani Radhikaraje and most importantly, have fun with jewellery. -

The Jewellery Market in the Eu

CBI MARKET SURVEY: THE JEWELLERY MARKET IN THE EU CBI MARKET SURVEY THE JEWELLERY MARKET IN THE EU Publication date: September 2008 CONTENTS REPORT SUMMARY 2 INTRODUCTION 5 1 CONSUMPTION 6 2 PRODUCTION 18 3 TRADE CHANNELS FOR MARKET ENTRY 23 4 TRADE: IMPORTS AND EXPORTS 32 5 PRICE DEVELOPMENTS 44 6 MARKET ACCESS REQUIREMENTS 48 7 OPPORTUNITY OR THREAT? 51 APPENDICES A PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 53 B INTRODUCTION TO THE EU MARKET 56 C LIST OF DEVELOPING COUNTRIES 57 This survey was compiled for CBI by Searce Disclaimer CBI market information tools: http://www.cbi.eu/disclaimer Source: CBI Market Information Database • URL: www.cbi.eu • Contact: [email protected] • www.cbi.eu/disclaimer Page 1 of 58 CBI MARKET SURVEY: THE JEWELLERY MARKET IN THE EU Report summary This survey profiles the EU market for precious jewellery and costume jewellery. The precious jewellery market includes jewellery pieces made of gold, platinum or silver all of which can be in plain form or with (semi-) precious gemstones, diamonds or pearls. The costume jewellery market includes imitation jewellery pieces of base metal plain or with semi-precious stones, glass, beads or crystals. It also includes imitation jewellery of any other material, cuff links and hair accessories. This survey excludes second-hand jewellery and luxury goods such as gold and silver smith’s ware (tableware, toilet ware, smokers’ requisites etc.) and watches. Consumption Being the second largest jewellery market after the USA, the EU represented 20% of the world jewellery market in 2007. EU consumers spent € 23,955 million with Italy, UK, France and Germany making up the lion’s share (70%). -

GEORGE W. BROWN the BRUNSWICK Hotel Lenox

BOSTON, MASS., FRIDAY. APRIL 14. 1905 1 0 GEORGE W.BROWN SHIRTINGS FOR 1905 ARE READY Copley Square All the Newest Ideas for.Men's Negligee and Nvlercbant Summer Wear in Hotel SHIRTS tailor Made from English, Scotch and French Fabrics. Huntington Aoe. & Exeter St. Private Designs. BUSINESS AND DRESS 110 TREMONT STREET SUITS PATRONAGE of "Tech" students $1.50, $2.00, $3.50, $4.50, $5.50 and solicited in our Cafe and Lunch Upward Room All made 27he attention of Secretaries Makes up-to-date students' in our own workrooms. Consult us to ana know the Linen, the Cravet and Gloves to Wear. Banquet Committees of Dining clothes at very reasonable Clubs, Societies, Lodges, etc., is GLOVES called to the fact that the Copley Fownes' Heavy Square prl;r., Street Gloves, hand Hotel has exceptionally I lStitched, $1.50. Better ones, $2.00, ood facilities $2.50 and $3.00. Men's and Women's for serving Breakfasts, Luncheons or Dinners and will cater NECKWEAR out of the ordinary-shapes strictly especially to Suits and Overcoats from $35 new-8-1.00 to $4.50. this trade. Amos H. Whipple, Proprietor This is the best time of the ENTIRE YEAR, N oy s Oi /ros.' Summer Streets, for you to have your FULL DRESS, Tuxedo, Boston, U. S. A. or Double-Breasted Frock Suit made. We make a Specialty of these garments and make Special Established I874 Prices during the slack season. Then again, we SPRING OPENING have an extra large assortment at this time, and DURGIN, PARK & CO,. -

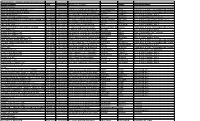

New Licenses

New Licenses - ALLIssued from 01/01/2021 to 09/01/2021 as of 09/01/2021 8:13 am Business Name Lic # IssuedDate Business Location Owner Type of Business Alcohol License 1800 MEXICAN RESTAURANT, LLC ALC13606 06/28/2021 5296 New Jesup Hwy Brunswick DURAN MARIN RAUL Liquor Beer & Wine Consumption On Premis BEACHCOMBER BBQ & GRILL ALC14200 08/25/2021 319 Arnold Rd St Simons Island PARROTT THOMAS Liquor Beer & Wine Consumption On Premis BPR BRUNSWICK LLC ALC13776 04/07/2021 116 Gateway Center Blvd BrunswickPATEL PANKAJ Beer & Wine Package Sales COBBLESTONE WHOLESALE ALC14190 08/25/2021 262 Redfern Vlg St Simons Island STEGER RHONDA Wine Consumption On Premises CRACKER BARREL OLD COUNTRY STORE, INC.ALC14060 07/26/2021 211 Warren Mason Blvd Brunswick CHRISTENSEN WILLIAM Beer & Wine Consumption On Premises DOLGENCORP,LLC ALC13837 05/13/2021 461 Palisade Dr Brunswick GILLIS MATIE Beer & Wine Package Sales DOLGENCORP,LLC ALC13923 05/12/2021 25 Cornerstone Ln Brunswick REID FEATHER Beer & Wine Package Sales DOROTHY'S COCKTAIL & OYSTER BAR ALC13687 03/19/2021 12 Market St St Simons Island AUFFENBERG JR. DANIEL Liquor Beer & Wine Consumption On Premis ELI CAIRO LLC ALC13631 01/07/2021 72 Altama Village Dr Brunswick MAZON ELI Beer & Wine Package Sales FRANCIE & MARTI LLC ALC13953 07/08/2021 295 Redfern Vlg A St Simons Island TOLLESON MARTI Wine Consumption On Premises FRANCIE & MARTI LLC ALC13954 07/08/2021 295 Redfern Vlg A St Simons Island TOLLESON MARTI Wine Package Sales GEORGIA CVS PHARMACY, LLC ALC13711 03/23/2021 1605 Frederica Rd St Simons Island