No Coward Plays Hockey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HMCS Montréal Achieves Significant Milestone with the CH-148 Cyclone by Slt Olivia Clarke, HMCS Montréal

A maritime Anzac Day milestone in Halifax First Cyclone flight RNZN sailors get a PSP fitness instructor trials at sea taste of home making waves at sea Pg. 7 Pg. 8 Pg. 9 Monday, May 16, 2016 Volume 50, Issue 10 Clearance Divers and Port Inspection Divers from FDU(A) take down the dive site after completing the fresh water pipe inspections at Ca- nadian Forces Station ALERT during Operation NUNALIVUT, April 9, 2016. CPL CHRIS RINGIUS, FIS HALIFAX Clearance Divers and Port Inspection Divers from FDU(A) dive un- der the ice to inspect fresh water intake pipes for Canadian Forces Clearance Divers and Port Inspection Divers from FDU(A)dive under the ice in the Arctic Ocean at Cana- Station ALERT during Operation NUNALIVUT, April 8, 2016. dian Forces Station ALERT during Operation NUNALIVUT, April 15, 2016. CPL CHRIS RINGIUS, FIS HALIFAX CPL CHRIS RINGIUS, FIS HALIFAX Building Arctic capabilities on Op NUNALIVUT 2O16 By Ryan Melanson, which is something people don’t eight divers from FDU(A) get- our equipment, because there’s Trident Staff get the opportunity to do often.” ting a chance. no local shop where we can go “People got their hands on “Just to be able to dive and borrow supplies or anything,” Operation NUNALIVUT 2016 experience, continuing to set up spend 20 minutes or a half hour, PO2 Beaton added. recently wrapped up in and the same gear for ice diving and cycle everyone through, “With the high pace of the unit around Resolute Bay and CFS again and again. It’s something that’s a success. -

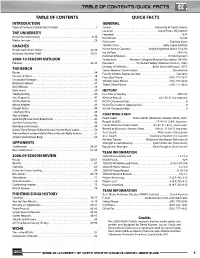

Table of Contents/Quick Facts Table Of

TABLE OF CONTENTS/QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS QUICK FACTS INTRODUCTION GENERAL Table of Contents/Quick Facts/Credits . .1 School . .University of North Dakota Location . Grand Forks, ND (58202) THE UNIVERSITY Founded . 1883 University Information . .2-25 Enrollment . 12,748 Media Services . .26 Nickname . .Fighting Sioux COACHES School Colors . Kelly Green & White Head Coach Brian Idalski . 28-29 Home Arena (Capacity) . Ralph Engelstad Arena (11,634) Assistant Coaches/Sta . 30-31 Ice Surface . .200 x 85 National A liation . .NCAA Division I 2009-10 SEASON OUTLOOK Conference . Western Collegiate Hockey Association (WCHA) Preview . 32-33 President . .Dr. Robert Kelley (Abilene Christian, 1965) Director of Athletics . Brian Faison (Missouri, 1972) THE BENCH Senior Woman Administrator . Daniella Irle Roster . .34 Faculty Athletic Representative . Sue Jeno Susanne Fellner . .35 Press Box Phone . (701) 777-3571 Cassandra Flanagan . .36 Athletic Dept. Phone . (701) 777-2234 Brittany Kirkham . .37 Ticket O ce Phone . (701) 777-0855 Alex Williams . .38 Kelly Lewis . .39 HISTORY Stephanie Roy . .40 First Year of Hockey . 2002-03 Sara Dagenais. .41 All-time Record . 62-150-21 (six seasons) Ashley Holmes . .42 NCAA Championships . .0 Kelsey Ketcher . .43 NCAA Tournament Appearances . .0 Margot Miller . .44 WCHA Championships . .0 Stephanie Ney . .45 Alyssa Wiebe . .46 COACHING STAFF Jorid Dag nrud/Janet Babchishin . .47 Head Coach . Brian Idalski (Wisconsin-Stevens Point, 2001) Jocelyne Lamoureux . .48 Record at UND . .17-41-10 (.324), two years Monique Lamoureux . .49 Career Record as Head Coach . 125-62-21 (.651), seven years Ashley Furia/Megan Gilbert/Jessica Harren/Mary Loken . .50 Record at Wisconsin-Stevens Point . .108-21-11 (.811), ve years Alanna Moir/Candace Molle/Allison Parizek/Holly Perkins . -

Hockeycanada.Ca/CENTENNIALCUP Hockeycanada.Ca/COUPEDUCENTENAIRE

MARITIME HOCKEY LEAGUE LIGUE DE HOCKEY JUNIOR (MHL) AAA DU QUÉBEC (LHJAAAQ) MHL Amherst Ramblers Forts de Chambly MHL Campbellton Tigers L’Everest de la Côte-du-Sud 131 TEAMS, 10 LEAGUES | 131 ÉQUIPES, 10 LIGUES Edmundston Blizzard Flames de Gatineau MHL Fredericton Red Wings Inouk de Granby Grand Falls Rapids Collège Français de Longueuil Miramichi Timberwolves Rangers de Montréal-Est Pictou County Crushers Arctic de Montréal-Nord South Shore Lumberjacks Titan de Princeville MANITOBA JUNIOR HOCKEY SASKATCHEWAN JUNIOR Summerside Western Capitals Prédateurs de Saint-Gabriel-de-Brandon LEAGUE (MJHL) HOCKEY LEAGUE (SJHL) LHJAAAQ Truro Bearcats Panthères de Saint-Jérôme SJHL Valley Wildcats Cobras de Terrebonne LHJAAAQ Yarmouth Mariners Braves de Valleyfield Dauphin Kings Battlefords North Stars Shamrocks du West Island Neepawa Natives Estevan Bruins SJHL OCN Blizzard Flin Flon Bombers LHJAAAQ Portage Terriers Humboldt Broncos COUPE ANAVET CUP COUPE FRED PAGE CUP SJHL Selkirk Steelers Kindersley Klippers Steinbach Pistons La Ronge Ice Wolves Swan Valley Stampeders Melfort Mustangs CENTRAL CANADA HOCKEY LEAGUE (CCHL) Virden Oil Capitals Melville Millionaires WEST/OUEST EAST/EST Waywayseecappo Wolverines Nipawin Hawks Winkler Flyers Notre Dame Hounds CCHL Winnipeg Blues Weyburn Red Wings MJHL Brockville Braves Navan Grads Yorkton Terriers CCHL Carleton Place Canadians Nepean Raiders Cornwall Colts Ottawa Jr. Senators MJHL Hawkesbury Hawks Pembroke Lumber Kings CCHL Kanata Lasers Rockland Nationals Kemptville 73’s Smiths Falls Bears MJHL PANTHÈRES -

2010-11 WCHA Women's Season-In-Review

WCHA Administrative Office Bruce M. McLeod Commissioner Carol LaBelle-Ehrhardt Assistant Commissioner of Operations Greg Shepherd Supervisor of Officials Mailing Address Western Collegiate Hockey Association 2211 S. Josephine Street, Room 302, Denver, CO 80210 p: 303 871-4223. f: 303 871-4770. [email protected] April 22, 2011 WCHA Women’s Office; Public Relations 2010-11 WCHA Women’s Season-in-Review Sara R. Martin Associate Commissioner University of Wisconsin Secures Record 12th Consecutive p: 608 829-0104. f: 608 829-0105. [email protected] National Championship for WCHA; Badgers Defeat BC & BU Doug Spencer Associate Commissioner for Public Relations to Claim 2011 NCAA Women’s Frozen Four in Erie, PA p: 608 829-0100. f: 608 829-0200. No. 1-Ranked Wisconsin Completes Trophy Hat Trick as Conference Regular Season Champions, [email protected] League Playoff Champions, Div. 1 National Champions; Badgers Conclude Campaign on 27- Bill Brophy Women’s Public Relations Director Game Unbeaten Streak; Wisconsin’s Meghan Duggan Named Patty Kazmaier Memorial Award p: 608-277-0282. Winner; Duggan Honored as WCHA Player of the Year to Highlight League Individual Awards; [email protected] Mailing Address Four WCHA-Member Teams Ranked Among Nation’s Top 10 in Final National Polls … Wisconsin Western Collegiate Hockey Association No. 1, Minnesota Duluth No. 5, Minnesota No. 6/7, North Dakota No. 9; WCHA Teams Combine 559 D’Onofrio Drive, Suite 103 Madison, WI 53719-2096 for 26-12-3 (.671) Non-Conference Record in 2010-11 WCHA Women’s League MADISON, Wis. – The University of Wisconsin made sure the streak continues for the Western Collegiate Hockey Bemidji State University Association. -

2018 Four Nations Cup Game Notes 2018 Four Nations Cup | Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada | Nov

2018 FOUR NATIONS CUP GAME NOTES 2018 FOUR NATIONS CUP | SASKATOON, SASKATCHEWAN, CANADA | NOV. 6-10, 2018 GAME ONE • USA (0-0-0-0) VS. FINLAND (0-0-0-0) • SASKTEL CENTRE • NOVEMBER 6, 2018 TODAY'S GAME 2018 FOUR NATIONS CUP Today is the first meeting between the U.S. and Finland at the The Four Nations Cup is an annual tournament that has been 2018 Four Nations Cup. The game will take place at 1 p.m. held in varying forms since 1996. This year marks the 23rd year (ET) at SaskTel Centre in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. of the tournament (previously the Three Nations Cup). Games Today's game will be streamed live on HockeyTV.com. Follow will be held at SaskTel Centre in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, the updates on Twitter @USAHockey and join the conversation Canada. The United States has competed in the tournament 21 by using #FourNations. The two teams last met in the semifinals times, having not participated in 2001. Team USA has captured at the 2018 Olympic Winter Games when the U.S. defeated the the title eight times (1997, 2003, 2008, 2011-12, 2015-17), fin- Fins, 5-0. Dani Cameranesi (Plymouth, Minn.) led the way for ished second 12 times and third in the tournament in 2013. The Team USA with two goals and an assist while Maddie Rooney Americans hold an overall record of 51-5-5-23-2 (W-OTW-OTL- (Andover, Minn.) made 14 saves on as many shots to advance L-T) in 86 Three/Four Nations Cup games. -

Télécharger La Page En Format

Portail de l'éducation de Historica Canada Canada's Game - The Modern Era Overview This lesson plan is based on viewing the Footprints videos for Gordie Howe, Bobby Orr, Father David Bauer, Bobby Hull,Wayne Gretzky, and The Forum. Throughout hockey's history, though they are not presented in the Footprints, francophone players like Guy Lafleur, Mario Lemieux, Raymond Bourque, Jacques Lemaire, and Patrick Roy also made a significant contribution to the sport. Parents still watch their children skate around cold arenas before the sun is up and backyard rinks remain national landmarks. But hockey is no longer just Canada's game. Now played in cities better known for their golf courses than their ice rinks, hockey is an international game. Hockey superstars and hallowed ice rinks became national icons as the game matured and Canadians negotiated their role in the modern era. Aims To increase student awareness of the development of the game of hockey in Canada; to increase student recognition of the contributions made by hockey players as innovators and their contributions to the game; to examine their accomplishments in their historical context; to explore how hockey has evolved into the modern game; to understand the role of memory and commemoration in our understanding of the past and present; and to critically investigate myth-making as a way of understanding the game’s relationship to national identity. Background Frozen fans huddled in the open air and helmet-less players battled for the puck in a -28 degree Celsius wind chill. The festive celebration was the second-ever outdoor National Hockey League game, held on 22 November 2003. -

Complimentary Contributor Copy Complimentary Contributor Copy PSYCHOLOGY of EMOTIONS, MOTIVATIONS and ACTIONS

Complimentary Contributor Copy Complimentary Contributor Copy PSYCHOLOGY OF EMOTIONS, MOTIVATIONS AND ACTIONS POSITIVE HUMAN FUNCTIONING FROM A MULTIDIMENSIONAL PERSPECTIVE VOLUME 3 PROMOTING HIGH PERFORMANCE No part of this digital document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means. The publisher has taken reasonable care in the preparation of this digital document, but makes no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assumes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of information contained herein. This digital document is sold with the clear understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, medical or any other professional services. Complimentary Contributor Copy PSYCHOLOGY OF EMOTIONS, MOTIVATIONS AND ACTIONS Additional books in this series can be found on Nova‟s website under the Series tab. Additional E-books in this series can be found on Nova‟s website under the E-book tab. Complimentary Contributor Copy PSYCHOLOGY OF EMOTIONS, MOTIVATIONS AND ACTIONS POSITIVE HUMAN FUNCTIONING FROM A MULTIDIMENSIONAL PERSPECTIVE VOLUME 3 PROMOTING HIGH PERFORMANCE A. RUI GOMES RUI RESENDE AND ALBERTO ALBUQUERQUE EDITORS New York Complimentary Contributor Copy Copyright © 2014 by Nova Science Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means: electronic, electrostatic, magnetic, tape, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the Publisher. For permission to use material from this book please contact us: Telephone 631-231-7269; Fax 631-231-8175 Web Site: http://www.novapublishers.com NOTICE TO THE READER The Publisher has taken reasonable care in the preparation of this book, but makes no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assumes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. -

Hockey Players Chosen Good — They Need Red-Hot Goaltend but They Also Tired out Their Keydale Hunter, Regarded by Many As Ing

The Prince George Citizen — Wednesday, April 20, 1988 — 13 MARK ALLAN S p o r t s Sports editor CALG ARY STIFLED IN FIRST-GAME LOSS S trategy sw itch beneficial for O ilers CALGARY (CP) — Successor the Edmonton Oilers used to de pend almost solely on their explosive offence. Poor series Tuesday night it was discipline, defence and penalty killing that enabled them to subdue the Calgary Flames 3-1 in the first game of the Sm ythe D ivision best-of-seven final. forgotten “Defensive hockey isn’t something we’re accustomed to, but we have to play Calgary this way,” said Craig MacTavish, who worked tirelessly killing off nine Calgary power plays. as Gallant In a reversal of past seasons, it was the Oilers who played strong defence and tne Flames who had the better offence. scores two “I don’t know if we’ve had a big ger win in our history,” saidC a p i t a l s ' DETROIT (AP) — Detroit for Wayne Gretzky, who scored on a ward Gerard Gallant, who felt he breakaway about three minutes af played poorly in the Norris Divi ter linemate Jari Kurri got the captain sion semi-finals, is making amends game-winning goal in the 13th min in the final. ute of the final period. i n j u r e d Gallant’s fourth playoff goal “It’s a big confidence builder. LANDOVER, Md. (AP) - Wash proved to be the margin of victory After all, they were first overall . ington defenceman Rod Langway Tuesday night as the Red Wings . -

Le Canada & Les Jeux Olympiques D‟Hiver „En Bref‟

Le Canada & les Jeux Olympiques d‟hiver „En bref‟ Introduction Le 12 février 2010, Vancouver sera la ville hôte des XXIes Jeux Olympiques d’hiver, elle accueillera les athlètes du monde et ceux du Canada. Cette célébration marquera un nouveau chapitre dans la longue et riche histoire de la participation canadienne aux Jeux d’hiver. Le Comité Olympique Canadien a envoyé des athlètes à toutes les éditions des Jeux Olympiques d’hiver et James Merrick, membre du Comité International Olympique (CIO) au Canada, fut un supporter passionné de l’idée de créer des Jeux d’hiver séparés. Lorsque la « Semaine de sports d’hiver », qui devait plus tard être reconnue rétroactivement par le CIO comme les premiers Jeux Olympiques d’hiver, eut lieu à Chamonix (France), du 25 janvier au 5 février 1924, un petit groupe de Canadiens étaient présents pour écrire les débuts de cette histoire. Les sports et les disciplines que pratiquent les Canadiens Aux Iers Jeux Olympiques d‟hiver, les hommes canadiens participèrent à trois des neuf sports et disciplines au programme : patinage de vitesse, hockey sur glace et patinage artistique. L’équipe canadienne de patinage de vitesse se composait d’un athlète : Charles Gorman. La délégation féminine était également limitée puisqu’elle ne comptait que Cecil Eustace. Eustace concourut en patinage artistique, dans l’épreuve individuelle et avec Melville Rogers dans l’épreuve par couple. Le programme olympique et la délégation canadienne se sont grandement développés au cours des vingt éditions des Jeux d’hiver célébrés jusqu’à présent. Aux XXes Jeux Olympiques d‟hiver à Turin en 2006, les athlètes canadiens ont pris part à l’ensemble des 15 sports et disciplines pour les hommes et aux 13 pour les femmes figurant au programme. -

Orientation and Training – Determined by Branch and Association

ORIENTATION AND TRAINING – DETERMINED BY BRANCH AND ASSOCIATION It is recommended that Association’s provide orientation and training sessions relevant to the position. Coaches - Hockey Canada’s National Coach Certification Program (NCCP) is a competency- Team Safety People / Board of based program. The program Officials Officials Officials enables coaches to build their Managers Trainers Directors coaching tools and knowledge of the game, so they can work effectively with their players. LEVEL I Purpose to LEVEL IV Purpose Hockey Canada Safety Managers Manual - See Association prepare a young or new to prepare hockey Program/HockeyTrainers LEVEL VI Purpose Appendix official to officiate minor officials capable of Certification Program Orientation To prepare hockey refereeing Senior, competent officials Coach Stream Junior A, B, C, D, capable of minor hockey refereeing at regional and LEVEL 2 Purpose to national further enhance the national championships and Association Meetings Association Meetings training and skills of championships, designated IIHF minor hockey officials. female hockey competition (i.e. Developmental Stream national Memorial Cup, RBC championships and Cup, Allan Cup, LEVEL III Purpose to designated minor Hardy Cup, prepare officials hockey IIHF University Cup, capable of refereeing competition, or CCAA finals, world minor hockey being a linesman in championships, playoffs, minor Major Junior, High Performance hockey regional Olympics, FISU Stream Junior A, Senior, playoffs and female Games). national CIS, CCAA, inter- championships, or branch and IIHF being linesmen in competition Junior B, C, D, Senior Association Meetings and Bantam or Association Midget regional LEVEL V Purpose to championships prepare meetings competent officials to referee Major Junior, Junior A, Senior, CIS, and inter-branch playoffs ORIENTATION AND TRAINING – DETERMINED BY BRANCH AND ASSOCIATION It is recommended that Association’s provide orientation and training sessions relevant to the position. -

Hockey Apparel Free Shipping

Hockey apparel free shipping Discounts average $11 off with a NHL Shop promo code or coupon. 34 NHL Shop coupons now on RetailMeNot. NHL Draft Hats Available 2, - Dec 31, Discounts average $10 off with a Gongshow Lifestyle Hockey Apparel promo code or coupon. 37 Gongshow Lifestyle Hockey Apparel coupons now on May 4, - Dec 31, No Sales Tax. Except CA. Free Same Day Shipping. On all orders over $ & before 4PM EST. Day Returns. Now easier than ever! Contact · Login. Discount Hockey carries the best selection of hockey equipment, ice skates, sticks, helmets, gloves, accessories, custom jerseys, goalie equipment, and more!Clearance · Skates · Sticks · Helmets. 50 best Gongshow Lifestyle Hockey Apparel coupons and promo codes. Save big on apparel and accessories. Today's top deal: $30 off. 8 verified NHL coupons and promo codes as of Oct Shop NHL Kid's Apparel The Hot Off The Ice sales section has discount merchandise of all types. Shop clearance hockey apparel & gear at DICK'S Sporting Goods today. Check out customer reviews and learn more about these great products. 29 Promo Codes for | Today's best offer is: Free Shipping on orders San Jose Sharks Western Conference Champions Fan Gear starting at $ women and kids. Get the latest NHL clothing and exclusive gear at hockey fan's favorite shop. Adidas Authentic NHL Jerseys; 9. NHL Coupons & Promos. Save up to 60% on select merchandise from ! Buy discounted shirts, hats, sweatshirts, and more apparel from the official store of the NHL. with coupon code ITP. coupons and deals also available for October Shop vintage NHL apparel with prices starting at $ NHL Shop Coupons, Promo Codes, and Discounts. -

Team China Vs

For immediate release Thursday, March 7, 2013 www.CWHL.ca CWHL CHAMPIONSHIP TROPHY THE CLARKSON CUP TO BE HOUSED PERMANENTLY IN HOCKEY HALL OF FAME TORONTO, Ont. – The Canadian Women’s Hockey League is excited to announce that the Clarkson Cup, awarded annually to the team that wins the CWHL championship, has a new home at the Hockey Hall of Fame in downtown Toronto. The Clarkson Cup, named after former Governor General of Canada Adrienne Clarkson, who served from 1999 to 2005, was officially donated to the Hockey Hall of Fame during a ceremony this morning in the Hockey Hall of Fame’s Spotlight Theatre. Special guests in attendance included The Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson herself, director of public affairs and assistant to the president of the Hockey Hall of Fame Ron Ellis, vice-president and curator of the Hockey Hall of Fame Phil Pritchard, Ontario Women’s Hockey Association president Fran Rider, CWHL commissioner Brenda Andress, 2013 Clarkson Cup chair Cathy Pin and CWHL players including Brampton Thunder forward Gillian Apps and Toronto Furies goaltender Sami Jo Small, who are both two-time Olympic gold medallists and accomplished alumnae of Canada’s National Women’s Team “I’m thrilled that the Clarkson Cup will be on display at the Hockey Hall of Fame to inspire women to play hockey to the best of their abilities,” the Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson said. “Women’s hockey has been a part of our nation for close to 100 years,” vice-president and curator of the Hockey Hall of Fame Phil Pritchard said.