Bauhaus Beginnings Reexamines the Founding Principles of This Landmark Institution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Große Berliner , Junge Und 'Alte in Den Galerien W Erner Scholz, Geor~E Gro&Z, Corpora, Emil Schumacher

11 "Große Berliner , Junge und 'Alte in den Galerien W erner Scholz, Geor~e Gro&z, Corpora, Emil Schumacher "Groß~' ist die ,.Berliner" vorläufig nur der ren und Uniformen, mit dem Hakenkreuz auf und daß diese ohne weiteres erkennbar wür• Zahl nach (ca. 1200 Werke), aber es kann dem Schlips und anderem Zierat, dann fragt den. Corpora ist trotz der Titel ·(Dunkler noch werden. Das Niveau der Münchner man sich. wieso diese Schießbudenfiguren Frühling. Schlaf. Halblaut) kein Lyriker, er müßte auch für Berlin erreichbar sein. wenn innerhalb eines demokratischen Staates das ist wie die meisten seiner Landsleute span man mehrGäste einlüde und gelegentlich eine 'Rennen gewinnen konnten. Die Frage, wie nungsreich und dramatisch, nur sehr indirekt, Sonderschau ausländischer Kollegen in Be weit Grosz heute noch aktuell ist, stellt sich und in seinen Mitteln gewählt. Er hat ein tracht zöge; es bliebe für die Berliner noch jeder Besucher der Ausstellung. wunderbares Nachtblau, das vielen seiner genug Platz in den großen Messehallen am Eine andere Frage ist, ob gegenwärtige Bilder (alle von 1957 bis 1958) einen Zug von Funkturm. Immerhin, was sich aus der wie Maler wie Corpora und Schumacher sich Heiterkeit nach überstandenen Katastrophen dergegründeten · "Juryfreien" unter Leitung außerhalb der Welt fühlen und art pur ve:c1eiht. des .. Berufsverbandes bildender Künstler machen oder ob in diesen Arbeiten genau so Für Schumacher ist die Farbe kein ästhe• Berlin" (Walter Wellenstein) entwickelt hat, viel Stellungnahme steckt wie bei Grosz. Nun, tisches Phänomen, eher ein konstruktives.. ist gut und notwendig, vielleicht weniger für Grosz war ein Einzelfall, neben ihm malten Seine Bilder sind oft hell wie eine sonnenooo~ die Kunst als für die nicht arrivierten Künst• Kandinsky und Klee, Max Ernst und Joan beschienene Felswand oder schwarz wie ein ler und dasPublikum, das immer noch glaubt, Miro6, und bei ihnen war in denselben zwan Bahrtuch oder rot wie eine Feuersbrunst. -

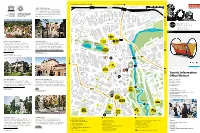

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

Ragioni E Sentimenti

RAGIONI E SENTIMENTI a cura di MARINA D’AMATO 2016 Università degli Studi Roma Tre Dipartimento di Scienze della Formazione RAGIONI E SENTIMENTI a cura di MARINA D’AMATO 2016 Desidero ringraziare tutti coloro che hanno contribuito con la loro disponibilità e professionalità a quest’opera, in modi diversi, ma tutti indispensabili: Katiuscia Carnà, Francesca Cubeddu, Milena Gammaitoni, Valentina Punzo e, in particolare, Edmondo Grassi che, quotidianamente, ha tenuto i contatti con gli autori e ha effettuato l’editing complessivo dell’opera. “A Gregorio” Coordinamento editoriale: Gruppo di Lavoro Edizioni: © Roma, dicembre 2016 ISBN: 978-88-97524-90-8 http://romatrepress.uniroma3.it Quest’opera è assoggettata alla disciplina Creative Commons attribution 4.0 International Licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) che impone l’attribuzione della paternità dell’opera, proibisce di alterarla, trasformarla o usarla per produrre un’altra opera, e ne esclude l’uso per ricavarne un profitto commerciale. Immagine di copertina: Federico Marcoaldi, Alla ricerca dell’azzurro (2015). Indice MARINA D’AMATO, Introduzione 5 PER UNA TEORIA DEI SENTIMENTI MONIQUE HIRSCHHORN, Quelle place pour l’affectivité en sociologie? 23 MARC-HENRY SOULET, La compassion: un faux ami pour l’analyse sociologique 33 VITTORIO COTESTA, Le Muse di Max Weber 47 ANNA DE STEFANO PERROTTA, Sorokin e i sentimenti dimenticati 65 BERNARDO CATTARINUSSI, Le espressioni dell’eudemonia 75 ADELE BIANCO, Ragioni e regole – sentimenti e capacità. L’attualità di un dualismo costante e problematico nella storia -

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

Sculptural Cubism in Product Design: Using Design History As a Creative Tool

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ENGINEERING AND PRODUCT DESIGN EDUCATION 3 & 4 SEPTEMBER 2015, LOUGHBOROUGH UNIVERSITY, DESIGN SCHOOL, LOUGHBOROUGH, UK SCULPTURAL CUBISM IN PRODUCT DESIGN: USING DESIGN HISTORY AS A CREATIVE TOOL Augustine FRIMPONG ACHEAMPONG and Arild BERG Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences ABSTRACT In Jan Michl's "Taking down the Bauhaus Wall: Towards living design history as a tool for better design", he explains how the history of design can become a tool for future design practices. He emphasizes how the aesthetics of the past still exist in the present. Although there have been a great deal of studies on the history of design, not much emphasis has been placed on Cubism, which is a very important part of design history. Many designs of the past, such as in the field of architecture and jewellery design, took their inspiration from sculptural cubism. The research question is therefore "How has sculptural Cubism influenced contemporary student product-design practices?" One research method used was the literature review, which was chosen to investigate what has been done in the past. Other methods used were interviews and focus groups, which were chosen to investigate what some contemporary design students knew about cubism. The researcher will also look to solicit knowledge from people outside the design community regarding designers and the work they do, as well as the general impression they have concerning design history and cubism. The concept of Cubism has been used in branding and as a marketing tool and in communication. Keywords: Design history, contemporary design practice, sculptural cubism, aesthetics. -

Irrational / Rational Production-Surrealism Vs The

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D/CI) Spring 2012 Professor Caroline A. Jones Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section. Department of Architecture Lecture 14 PRODUCTION AND (COMMODITY) FETISH: key dates: Lecture 14: Irrational Rational Production: Bauhaus 1919 (Sur)realism vs. the Bauhaus Idea Surrealism 1924 “The ultimate, if distant, objective of the Bauhaus is the Einheitskunstwerk- the great building in which there will be no boundary between monumental and decorative art.” -Walter Gropius (Bauhaus Manifesto. 1919) “Little by little the contradictory signs of servitude and revolt reveal themselves in all things.” - the Surrealist. Georges Bataille, 1929 “Bauhaus is the name of an artistic inspiration.” - Asger Jom, writing to Max Bill, 1954. “Bauhaus is not the name of an artistic inspiration, but the meaning of a movement that represents a well-defined doctrine.” -Bill to Jorn. 1954 “If Bauhaus is not the name of an artistic inspiration. it is the name of a doctrine without inspiration - that is to say. dead.'” - Jom 's riposte. 1954 “Issues of surrealist heterogeneity will be resolved around the semiological functions of photography rather than the formal properties … of style.” -Rosalind Krauss, 1981 I. Review: Duchamp, Readymade as fetish? Fountain by “R. Mutt,” 1917 II. Rational Production: the Bauhaus, 1919 - 1933 A. What's in a name? (Bauhaus” was a neologism coined by its founder, Walter Gropius, after medieval “Bauhütte”) The prehistory of Reform. B. Walter Gropius's goal: “to create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftstnan and artist. [...] painting and sculpture rising to heaven out of the hands of a million craftsmen, the crystal symbol of the new faith of the future.” C. -

The Archive of Renowned Architectural Photographer

DATE: August 18, 2005 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE GETTY ACQUIRES ARCHIVE OF JULIUS SHULMAN, WHOSE ICONIC PHOTOGRAPHS HELPED TO DEFINE MODERN ARCHITECTURE Acquisition makes the Getty one of the foremost centers for the study of 20th-century architecture through photography LOS ANGELES—The Getty has acquired the archive of internationally renowned architectural photographer Julius Shulman, whose iconic images have helped to define the modern architecture movement in Southern California. The vast archive, which was held by Shulman, has been transferred to the special collections of the Research Library at the Getty Research Institute making the Getty one of the most important centers for the study of 20th-century architecture through the medium of photography. The Julius Shulman archive contains over 260,000 color and black-and-white negatives, prints, and transparencies that date back to the mid-1930s when Shulman began his distinguished career that spanned more than six decades. It includes photographs of celebrated monuments by modern architecture’s top practitioners, such as Richard Neutra, Frank Lloyd Wright, Raphael Soriano, Rudolph Schindler, Charles and Ray Eames, Gregory Ain, John Lautner, A. Quincy Jones, Mies van der Rohe, and Oscar Niemeyer, as well as images of gas stations, shopping malls, storefronts, and apartment buildings. Shulman’s body of work provides a seminal document of the architectural and urban history of Southern California, as well as modernism throughout the United States and internationally. The Getty is planning an exhibition of Shulman’s work to coincide with the photographer’s 95th birthday, which he will celebrate on October 10, 2005. The Shulman photography archive will greatly enhance the Getty Research Institute’s holdings of architecture-related works in its Research Library, which -more- Page 2 contains one of the world’s largest collections devoted to art and architecture. -

Spring 2015 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

theGETTY A WORLD OF ART, RESEARCH, CONSERVATION, AND PHILANTHROPY | Spring 2015 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE theGETTY Spring 2014 TABLE OF President’s Message 3 by James Cuno President and CEO, the J. Paul Getty Trust CONTENTS New and Noteworthy 4 Earlier this year I attended the World Economic Forum in Keeping it Modern 6 Davos, Switzerland, during which government officials and corporate, education, and cultural leaders gather to explore Darkroom Alchemists Reinvent Photography 14 the economic and political prospects for the coming year. I gave a presentation about the ways in which digital technol- A Sense of Place in the City of Angels 20 ogy is transforming the museum experience—from initial dis- covery, to visiting, to research and collaboration, to the ways Thousands of Rare Books on your Desktop 24 in which visitors can engage more deeply with the collection through digital resources. This issue of The Getty expands Book Excerpt: J. M. W. Turner: Painting Set Free 27 on our previous coverage of how the Getty is “going digital” through projects like the HistoricPlacesLA initiative from the New from Getty Publications 28 Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) and the many digital fac- ets that are accessible to researchers and patrons around the From The Iris 30 world from the Getty Research Institute Library. Last month, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti joined GCI New Acquisition 31 Director Tim Whalen, Foundation Director Deborah Marrow, and me to launch HistoricPlacesLA, the city’s groundbreaking Getty Events 32 new system for mapping and inventorying historic resources in Los Angeles. HistoricPlacesLA contains information gath- Exhibitions 34 ered through SurveyLA—a citywide survey of LA’s significant historic resources—a public/private partnership between the From the Vault 35 City of Los Angeles and the Getty, including both the GCI and Foundation. -

David Quigley Learning to Live: Preliminary Notes for a Program Of

David Quigley In an essay published in 2009, Boris could play in a broader social context influenced the founding director John Groys makes the claim that “today art beyond the narrow realm of the art Andrew Rice, as well as the professors Learning to Live: education has no definite goal, no world. Josef Albers, Merce Cunningham, Robert Preliminary Notes method, no particular content that can Motherwell, John Cage, and the poets be taught, no tradition that can be Performing Pragmatism: Robert Creeley and Charles Olson. for a Program of Art transmitted to a new generation—which Art as Experience Unlike other trajectories of the critique Education for the is to say, it has too many.”69 While one On the first pages of Dewey’s Art as of the art object, the Deweyian tradition might agree with this diagnosis, one Experience from 1934, we read: did not deny the special status of art in 21st Century. immediately wonders how we should itself but rather resituated it within a Après John Dewey assess it. Are we to merely tacitly “By one of the ironic perversities that continuum of human experience. Dewey, acknowledge this situation or does this often attend the course of affairs, the as a thinker of egalitarianism and critique imply a call for change? Is this existence of the works of art upon which democracy, created a theory of art lack (or paradoxical overabundance) of the formation of an aesthetic theory based on the fundamental continuity goals, methods or content inherent to depends has become an obstruction of experience and practice, making the very essence of art education, or is to theory about them. -

"Pictures Made of Wool": the Gender of Labor at the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop (1919-23)

Tai Smith - "Pictures made of wool": The Gender of Labor at the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop (1919-23) Back to Issue 4 "Pictures made of wool": The Gender of Labor at the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop (1919-23) by T'ai Smith © 2002 In 1926, one year after the Bauhaus had moved to Dessau, the weaving workshop master Gunta Stölzl dismissed the earlier, Weimar period textiles, such as Hedwig Jungnik’s wall hanging from 1922 [Fig. 1], as mere “pictures made of wool.”1 In this description she differentiated the early weavings, from the later, “progressivist” textiles of the Dessau workshop, which functioned industrially and architecturally: to soundproof space or to reflect light. The weavings of the Weimar years, by contrast, were autonomous, ornamental pieces, exhibited in the fashion of paintings. Stölzl saw this earlier work as a failure because it had no progressive aim. The wall hangings of the Weimar workshop were experimental—concerned with the pictorial elements of form and color—yet at that they were still inadequate, without the larger, transcendental goals of painting, as in the Bauhaus painter Wassily Kandinsky’s Red Spot II from 1921. Stölzl assessed the earlier, “aesthetic” period of weaving as unsuccessful, because its specific strengths were neither developed nor theorized. Weaving in the early Bauhaus lacked its own discursive parameters, just as it lacked a disciplinary history. Evaluated against the “true” picture, painting, weaving appeared a weaker, ineffectual medium. Stölzl’s remark references a fundamental problem that goes unquestioned in the literature concerning the Weimar Bauhaus weaving workshop and the feminized status of the medium. -

Johannes Itten Wieder in Bern : Eine Ausstellung Über Das Frühe Bauhaus

Johannes Itten wieder in Bern : eine Ausstellung über das frühe Bauhaus Autor(en): Höhne, Günter Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Hochparterre : Zeitschrift für Architektur und Design Band (Jahr): 8 (1995) Heft 1-2 PDF erstellt am: 29.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-120140 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch dem Gesamtkunstwerk strebenden Aufbruchjahre des Bauhauses. Nun Johannes Itten wird das «vergessene» Bauhaus zugänglich, anschaulich erfahrbar gemacht. Und da ist an grossen Namen und Werken wahrlich kein Mangel: Neben Itten-Originalen sind viele wieder in Bern weitere, unter anderem von Muche, Klee, Feininger, Kandinsky, Schlemmer und Marcks präsentiert.