Cultural Heritage Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019 Journal of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. In this issue: Variation in songs of the White-eared Honeyeater Phenotypic diversity in the Copperback Quailthrush and a third subspecies Neonicotinoid insecticides Bird Report, 2011-2015: Part 1, Non-passerines President: John Gitsham The South Australian Vice-Presidents: Ornithological John Hatch, Jeff Groves Association Inc. Secretary: Kate Buckley (Birds SA) Treasurer: John Spiers FOUNDED 1899 Journal Editor: Merilyn Browne Birds SA is the trading name of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. Editorial Board: Merilyn Browne, Graham Carpenter, John Hatch The principal aims of the Association are to promote the study and conservation of Australian birds, to disseminate the results Manuscripts to: of research into all aspects of bird life, and [email protected] to encourage bird watching as a leisure activity. SAOA subscriptions (e-publications only): Single member $45 The South Australian Ornithologist is supplied to Family $55 all members and subscribers, and is published Student member twice a year. In addition, a quarterly Newsletter (full time Student) $10 reports on the activities of the Association, Add $20 to each subscription for printed announces its programs and includes items of copies of the Journal and The Birder (Birds SA general interest. newsletter) Journal only: Meetings are held at 7.45 pm on the last Australia $35 Friday of each month (except December when Overseas AU$35 there is no meeting) in the Charles Hawker Conference Centre, Waite Road, Urrbrae (near SAOA Memberships: the Hartley Road roundabout). Meetings SAOA c/o South Australian Museum, feature presentations on topics of ornithological North Terrace, Adelaide interest. -

Southern Safari Adelaide to Ceduna and Return

8 Nights Southern Safari Adelaide to Ceduna and Return ITINERARY SOUTHERN SAFARI Itinerary Map Ceduna South Australia Coffin Bay Port Lincoln Southern Safari Kangaroo Island Terms & Conditions This is a sample itinerary only. Prevailing conditions, local arrangements and indeed, what we discover on the day, may cause variation. Charter flight between Ceduna and Adelaide is INCLUDED in the tariff. SOUTHERN SAFARI ITINERARY A safari at sea Revel in a sumptuous lunch at Maggie Beer’s Farm, sample the many delights of famed Kangaroo Island and wash down oysters with champagne in beautiful Coffi n Bay. Then mix-in cage diving with great white sharks and some of Australia’s most reliable fi shing action and, you’ve got a safari with a diff erence! Includes return fl ight from Ceduna to Adelaide. Day Welcome Aboard 01 Start your cruise with a diff erence! Our comfortable coach will collect you from the doorstep of our partner hotel and deliver you to the foothills of Adelaide. Together with stunning views of the city, Penfolds’ Magill Estate also off ers breathtaking views of its vines – the perfect setting to immerse one’s self in Australia’s most iconic wine label! Discover historic Magill Estate – the birthplace of Penfolds with a rich history dating back to 1844 and, indulge in a luxurious experience of storytelling and tasting. Continuing with a theme of iconic infl uences, next stop is The Farm Eatery - the home of Australia’s kitchen queen, Maggie Beer. In the early 1970s, Maggie and her husband moved to the Barossa Valley and established The Pheasant Farm Restaurant. -

STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS PLAN 2021-2030 Ii CITY of PORT LINCOLN – Strategic Directions Plan CONTENTS

CITY OF PORT LINCOLN STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS PLAN 2021-2030 ii CITY OF PORT LINCOLN – Strategic Directions Plan CONTENTS 1 FOREWORD 2 CITY PROFILE 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY 5 COMMUNITY ASPIRATIONS 6 VISION, MISSION and VALUES 8 GOAL 1. ECONOMIC GROWTH AND OPPORTUNITY 10 GOAL 2. LIVEABLE AND ACTIVE COMMUNITIES 12 GOAL 3. GOVERNANCE AND LEADERSHIP 14 GOAL 4. SUSTAINABLE ENVIRONMENT 16 GOAL 5. COMMUNITY ASSETS AND PLACEMAKING 18 MEASURING OUR SUCCESS 20 PLANNING FRAMEWORK 21 COUNCIL PLANS Prepared by City of Port Lincoln Adopted by Council 14 December 2020 RM: FINAL2020 18.80.1.1 City of Port Lincoln images taken by Robert Lang Photography FOREWORD On behalf of the City of Port Lincoln I am pleased to present the City's Strategic Directions Plan 2021-2030 which embodies the future aspirations of our City. This Plan focuses on and shares the vision and aspirations for the future of the City of Port Lincoln. The Plan outlines how, over the next ten years, we will work towards achieving the best possible outcomes for the City, community and our stakeholders. Through strong leadership and good governance the Council will maintain a focus on achieving the Vision and Goals identified in this Plan. The Plan defines opportunities for involvement of the Port Lincoln community, whether young or old, business people, community groups and stakeholders. Our Strategic Plan acknowledges the natural beauty of our environment and recognises the importance of our natural resources, not only for our community well-being and identity, but also the economic benefits derived through our clean and green qualities. -

Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla Grammar This Book Is Available As a Free Fully-Searchable Ebook from Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla Grammar

Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar This book is available as a free fully-searchable ebook from www.adelaide.edu.au/press Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar A commentary on the first section of A vocabulary of the Parnkalla language (revised edition 2018) by Mark Clendon Linguistics Department, Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide Clamor Wilhelm Schürmann Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press The University of Adelaide Level 14, 115 Grenfell Street South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes externally refereed scholarly books by staff of the University of Adelaide. It aims to maximise access to the University’s best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2015 Mark Clendon, 2018 for this revised edition This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. Address all inquiries to the Director at the above address. For the full Cataloguing-in-Publication data please contact the National Library of Australia: [email protected] -

TRAVEL Eyre Peninsula, South Australia

TRAVEL Eyre Peninsula, South Australia CaptionPort Lincolnhere National Park is dotted with caves. Eyre Peninsula From the Ocean to the Outback XPERIENCE THE UNTOUCHED through massive sand dunes, swimming Eand remote beauty of the Eyre with Australian sea lions and dolphins Peninsula in South Australia. From at the same time (the only place in spectacular coastal landscapes to the Australia where you can do this), wildly beautiful outback, and the visiting arguably Australia’s best native wildlife that call them home, you'll revel koala experience, seeing landscapes in the diversity of this genuine ocean-to- that only a few ever see from the raw, outback tour. rugged and natural coastline to the ep SA Unsurpassed in its beauty, this extraordinary colours of the red sands, region also teems with another truly blue skies and glistening white salt lakes AG TRAVEL special quality - genuine hospitality of the Gawler Ranges. from its colourful characters. You'll The icing on the cake of this trip is Dates: meet a host of locals during your visit the opportunity to sample the bounty of 10–18 Feb 2021 to Port Lincoln, the seafood capital of the ocean here, including taking part in 26 Feb–7 March 2021 Australia, and the stunning, ancient and a seafood masterclass with marron and 24 ApriL–2 May 2021 geologically fuelled Gawler Ranges. oysters direct from the local farms. 9–17 Oct 2021 Each day you'll enjoy memorable Accommodation is on Port Lincoln’s email: and unique wildlife, geological, foreshore overlooking Boston Bay, and [email protected] culinary, photographic and educational then, in the outback, at Kangaluna phone: 0413 560 210 experiences, including a 4WD safari Luxury Bush Camp. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

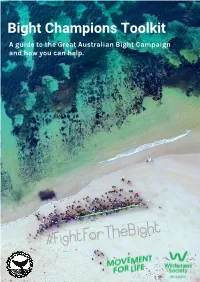

Bight Champions Toolkit a Guide to the Great Australian Bight Campaign and How You Can Help

Bight Champions Toolkit A guide to the Great Australian Bight Campaign and how you can help. Contents Great Australian Bight Campaign in a nutshell 2 Our Vision 2 Who is the Great Australian Bight Alliance? 3 Bight Campaign Background 4 A Special Place 5 The Risks 6 Independent oil spill modelling 6 Quick Campaign Snapshot 7 What do we want? 8 What you can do 9 Get the word out there 10 How to be heard 11 Writing it down 12 Comments on articles 13 Key Messages 14 Media Archives 15 Screen a film 16 Host a meet-up 18 Setting up a group 19 Contacting Politicians 20 Become a leader 22 Get in contact 23 1 Bight campaign in a nutshell THE PLACE, THE RISKS AND HOW WE SAVE IT “ The Great Australian Bight is a body of coast Our vision for the Great and water that stretches across much of Australian Bight is for a southern Australia. It’s an incredible place, teaming with wildlife, remote and unspoiled protected marine wilderness areas, as well as being home to vibrant and thriving coastal communities. environment, where marine The Bight has been home to many groups of life is safe and healthy. Our Aboriginal People for tens of thousands of years. The region holds special cultural unspoiled waters must be significance, as well as important resources to maintain culture. The cliffs of the Nullarbor are valued and celebrated. Oil home to the Mirning People, who have a special spills are irreversible. We connection with the whales, including Jidarah/Jeedara, the white whale and creation cannot accept the risk of ancestor. -

EPLGA Draft Minutes 4 Sep 15.Docx 1

Minutes of the Eyre Peninsula Local Government Association Board Meeting held at Wudinna Community Club on Friday 4 September 2015 commencing at 10.10am. Delegates Present: Bruce Green (Chair) President, EPLGA Roger Nield Mayor, District Council of Cleve Allan Suter Mayor, District Council of Ceduna Kym Callaghan Chairperson, District Council of Elliston Eddie Elleway Councillor, District Council of Franklin Harbour Dean Johnson Mayor, District Council of Kimba Julie Low Mayor, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula Neville Starke Deputy Mayor, City of Port Lincoln Sherron MacKenzie Mayor District Council of Streaky Bay Sam Telfer Mayor District Council of Tumby Bay Tom Antonio Deputy Mayor, City of Whyalla Eleanor Scholz Chairperson, Wudinna District Council Guests/Observers: Tony Irvine Executive Officer, EPLGA Geoffrey Moffatt CEO, District Council of Ceduna Peter Arnold CEO, District Council of Cleve Phil Cameron CEO, District Council of Elliston Dave Allchurch Councillor, District Council of Elliston Eddie Elleway Councillor, District Council of Franklin Harbour Daryl Cearns CEO, District Council of Kimba Debra Larwood Manager Corporate Services, District Council of Kimba Leith Blacker Acting CEO, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula Rob Donaldson CEO, City of Port Lincoln Chris Blanch CEO, District Council of Streaky Bay Trevor Smith CEO, District Council of Tumby Bay Peter Peppin CEO, City of Whyalla Adam Gray Director, Environment, LGA of SA Matt Pinnegar CEO, LGA of SA Jo Calliss Regional Risk Coordinator, Western Eyre -

Extract from the National Native Title Register

Extract from the National Native Title Register Determination Information: Determination Reference: Federal Court Number(s): SAD6011/1998 NNTT Number: SCD2016/001 Determination Name: Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia Date(s) of Effect: 6/04/2018 Determination Outcome: Native title exists in parts of the determination area Register Extract (pursuant to s. 193 of the Native Title Act 1993) Determination Date: 23/06/2016 Determining Body: Federal Court of Australia ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: Note 1: On 6 April 2018 Justice White of the Federal Court of Australia (the Court) ordered that: 1. The Determination of native title made on 23 June 2017 [sic] in Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia (No 2) [2016] FCA 724 be amended in accordance with the Amended Determination attached as Annexure A to this order, noting that because of the size of the Determination Annexure A comprises only: a. pages i to xv inclusive of the Amended Determination; b. the first page of any Schedule which is amended; and c. the particular pages within each Schedule which are amended. 2. Order 2 made on 23 June 2016 be vacated. 3. In its place there be an order that the Determination as amended take effect from the date of this order. Note 2: In the Determination orders of 23 June 2016, Order 22 deals with the nomination of a prescribed body corporate. On 19 December 2016 the applicant nominated to the Court in accordance with sections 56 and 57 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) that: (a) native title is not to be held in trust; National Native Title Tribunal Page 1 of 20 Extract from the National Native Title Register SCD2016/001 and, accordingly, pursuant to Order 22(b) of 23 June 2016: (b) the Barngarla Determination Aboriginal Corporation is nominated as the prescribed body corporate for the purpose of section 57(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). -

Port Neill Structure Plan from July 2013 to August 2013

INTERIM REPORT MASTERPLAN IN ASSOCIATION WITH IAN ROBERTSON DESIGN PORT NEILL SUSTAINABLE FUTURE STRUCTURE PLAN PORT NEILL SUSTAINABLE FUTURE STRUCTURE PLAN INTERIM REPORT in association with Ian Robertson Design Prepared by MasterPlan SA Pty Ltd ABN 30 007 755 277, ISO 9001:2008 Certified 33 Carrington Street, Adelaide SA 5000 Telephone: 8221 6000, masterplan.com.au December 2013 Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 4 1.1 Structure Planning Process.....................................................4 1.2 Public Consultation Process ...................................................7 1.3 Study Area and Strategic Direction .......................................7 2.0 BACKGROUND AND REGIONAL CONTEXT ............. 14 2.1 Tumby Bay & Port Neill ........................................................14 2.2 Demographic Data ................................................................15 2.3 Growth Scenarios ..................................................................17 2.4 Land Supply Analysis ............................................................19 3.0 VISION AND DESIGN PRINCIPLES ............................ 28 3.1 Port Neill Vision .....................................................................28 3.2 Guiding Design Principles .....................................................29 4.0 STRUCTURE PLAN ...................................................... 34 4.1 Port Neill Township ...............................................................34 4.2 Town Centre and Foreshore -

Southern Eyre Subregional Description

Southern Eyre Subregional Description Landscape Plan for Eyre Peninsula - Appendix C Southern Eyre comprises a land area of around 6,500 square kilometres, along with a large marine area. The southern boundary extends east from Spencer Gulf to the Southern Ocean, while the northern boundary extends along the agricultural plains north of Cummins. QUICK STATS Population: Approximately 23,500 Major towns (population): Port Lincoln (16,000), Tumby Bay (1,474), Cummins (719), Coffin Bay (615) Traditional Owners: Barngarla and Nauo nations Local Governments: Port Lincoln City Council, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula and District Council of Tumby Bay Land Area: Approximately 6,500 square kilometres Main land uses (% of land area): Cropping and grazing (63%), conservation (34%) Main industries: Fishing, aquaculture, agriculture, retail trade, health and community services, tourism, construction, mining Annual Rainfall: 340 – 560mm Highest elevation: Marble Range (436 metres AHD) Coastline length: 710 kilometres (excludes islands) Number of Islands: 113 2 Southern Eyre Subregional Description Southern Eyre What’s valued in Southern Eyre enjoy camping, 4WD adventures and walking. The pristine environment at Memory Cove and Coffin The Southern Eyre community is intrinsically linked Bay’s remoteness and wildness, provide a sense of to the natural environment with its identity ingrained adventure and place. in the “great outdoors”. Many people have their own favourite spot where they go to unwind and feel a Sir Joseph Banks Group are magic sense of place. For some it is their own patch, for parts of the world. They have an others it is a secluded beach or an adventure in the abundance of marine and birdlife bush. -

Port Spencer Grain Export Facility Peninsula Ports

Port Spencer Grain Export Facility Peninsula Ports Amendment to Public Environmental Report IW219900-0-NP-RPT-0003 | 2 8 November 2019 Amend ment to Pu blic Envir onm ental Rep ort Peninsula P orts Amendment to Public Environmental Report Port Spencer Grain Export Facility Project No: IW219900 Document Title: Amendment to Public Environmental Report Document No.: IW219900-0-NP-RPT-0003 Revision: 2 Date: 8 November 2019 Client Name: Peninsula Ports Client No: Client Reference Project Manager: Scott Snedden Author: Alana Horan File Name: J:\IE\Projects\06_Central West\IW219900\21 Deliverables\AMENDMENT TO THE PER\Amendment to PER_Rev 2.docx Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited ABN 37 001 024 095 Level 3, 121 King William Street Adelaide SA 5000 Australia www.jacobs.com © Copyright 2020 Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Limitation: This document has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Jacobs’ client, and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between Jacobs and the client. Jacobs accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this document by any third party. Document history and status Revision Date Description By Review Approved H 31.10.2019 Draft AH NB SS 0 1.11.2019 Draft issued to DPTI AH SS DM 1 8.11.2019 Issued to DPTI AH SS DM 2 13.1.2020 Re-issued Volume 1 to DPTI.