Rubber Stamp AG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birmingham, Alabama Event Hosted by Bill & Linda Daniels Re

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu April 8, 1994 TO: SENATOR DOLE FROM: MARCIE ADLER RE: BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA EVENT HOSTED BY BILL & LINDA DANIELS RE: ELIEHUE & NANCY BRUNSON ELIEHUE BRUNSON, FORMER KC REGIONAL ADMINISTRATOR, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR, HAS ADVISED ME THAT HE IS ATTENDING THIS EVENT AND HAS OFFERED TO HELP US IN THE ALABAMA AREA. (I'M SENDING THAT INFO TO C.A.) ELIEHUE WAS APPOINTED BY PRESIDENT BUSH AND DROVE MRS. DOLE DURING THE JOB CORPS CENTER DEDICATION IN MANHATTAN. ALTHOUGH LOW-KEY, HE DID WATCH OUT FOR OUR INTERESTS DURING THE JOB CORPS COMPLETION. HE ALSO DEFUSED A POTENTIAL RACIALLY SENSITIVE SITUATION IN KCK WHEN GALE AND I WERE STUMPED AND CALLED HIM FOR ADVICE. ELIEHUE AND NANCY MOVED TO BIRMINGHAM AFTER TCI - COMMUNICATIONS HIRED HIM TO SERVE AS REGIONAL GENERAL COUNSEL. YOUR LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION WAS A KEY FACTOR IN HIS HIRE. Page 1 of 55 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 111 AP 04-08-94 12:06 EST 29 Lines. Copyright 1994. All rights reserved. PM-AL-ELN--Governor-James,200< URGENT< Fob James to Run for Governor Again as Republican< BIRMINGHAM, Ala. (AP) Former Gov. Fob James decided toda to make a fourth bid fo s a Re ublican. Jack Williams, executive director of the Republican Legislative Caucus and chairman of the Draft Fob James Committee, said James would qualify at 3 p.m. today at the State Republicans Headquarters in Birmingham. -

![Presidential Files; Folder: 9/25/78 [2]; Container 92](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8687/presidential-files-folder-9-25-78-2-container-92-168687.webp)

Presidential Files; Folder: 9/25/78 [2]; Container 92

9/25/78 [2] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 9/25/78 [2]; Container 92 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) FORM OF CORRESPONDENTS OR TiTLE DAliE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT Memo Harold Brown to Pres. Carter, w/attachments 4 pp., ·r!=!:Defense Summary 9/22/78 A , ' Cabinet Summari. s Andrew Ypung to Pres. Carter~ 1 pg., re:UN activities 9/15/78 9/22/78 A Capinet' Summa:ri s Cal.ifq:no . to Pres. Carter, 3 pp. , re: Personnel "changes 9/22/7.$ c .:~ 0 '· i ~"d. 'I ".'' ' a ~~~·.0 .:t'' '~ ,, 11 , .. "~ •) •· ·~· ',,• \:l,. ,j; ~··~-·< ·-·... • 1 ' .} "I. " 1~ •: , dJ~ ·, '0 ·., " ~ ~r-~ 1\ ~ '·;P. , .. " . ,, ~ 1 , .. ··~ ·:. •·,· '"" <':'• :..·) .,0 / ~ ;w . • '' .• ~ U',• "·',, If' ~' • ·~ ~ ~· • ~ c , " ill" : " ,·, "''t> ''., ' : "."" ~:~~.,,~ . .. r " ·i ' '· ·: ., .~.~ ' 1. ~. ' , .. ;, ~, (• '• ·f." J '',j> '~~'!, ~' -o," :~ ~ ~ e' . " ' ~ ,· J ', I I. FIWE LOCATION Carter Presidenti,al Pap.ers-Staff Offices, Office .of Staff Sec. -Presidenti?l HandwritiRg File, 9/25/78 [2] Box-103 R.ESTRICTtiON CODES (AI Closed by Executive Order 1235S'governing access to national security information. (6) .Closed by statute or by the agency Which originated tine document. (C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gif,t. ~. NATIONAL ARCHIV.S AND RECORDS AOMINISTRA TION. NA FORM 1429 (6-8,5) ' . THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON 9/25/78 Tim Kraft The attached was returned in the President's outbox: It is forwarded to you for appropriate han<D:ing. Rick Hutcheson cc: Frank Moore THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON 9/25/78 rick-~- although pr.esident is sending note to tim ... -

Drowning in Data 15 3

BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE WHAT THE GOVERNMENT DOES WITH AMERICANS’ DATA Rachel Levinson-Waldman Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law about the brennan center for justice The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is a nonpartisan law and policy institute that seeks to improve our systems of democracy and justice. We work to hold our political institutions and laws accountable to the twin American ideals of democracy and equal justice for all. The Center’s work ranges from voting rights to campaign finance reform, from racial justice in criminal law to Constitutional protection in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution — part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group, part communications hub — the Brennan Center seeks meaningful, measurable change in the systems by which our nation is governed. about the brennan center’s liberty and national security program The Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program works to advance effective national security policies that respect Constitutional values and the rule of law, using innovative policy recommendations, litigation, and public advocacy. The program focuses on government transparency and accountability; domestic counterterrorism policies and their effects on privacy and First Amendment freedoms; detainee policy, including the detention, interrogation, and trial of terrorist suspects; and the need to safeguard our system of checks and balances. about the author Rachel Levinson-Waldman serves as Counsel to the Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program, which seeks to advance effective national security policies that respect constitutional values and the rule of law. -

Who Is the Attorney General's Client?

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\87-3\NDL305.txt unknown Seq: 1 20-APR-12 11:03 WHO IS THE ATTORNEY GENERAL’S CLIENT? William R. Dailey, CSC* Two consecutive presidential administrations have been beset with controversies surrounding decision making in the Department of Justice, frequently arising from issues relating to the war on terrorism, but generally giving rise to accusations that the work of the Department is being unduly politicized. Much recent academic commentary has been devoted to analyzing and, typically, defending various more or less robust versions of “independence” in the Department generally and in the Attorney General in particular. This Article builds from the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Co. Accounting Oversight Board, in which the Court set forth key principles relating to the role of the President in seeing to it that the laws are faithfully executed. This Article draws upon these principles to construct a model for understanding the Attorney General’s role. Focusing on the question, “Who is the Attorney General’s client?”, the Article presumes that in the most important sense the American people are the Attorney General’s client. The Article argues, however, that that client relationship is necessarily a mediated one, with the most important mediat- ing force being the elected head of the executive branch, the President. The argument invokes historical considerations, epistemic concerns, and constitutional structure. Against a trend in recent commentary defending a robustly independent model of execu- tive branch lawyering rooted in the putative ability and obligation of executive branch lawyers to alight upon a “best view” of the law thought to have binding force even over plausible alternatives, the Article defends as legitimate and necessary a greater degree of presidential direction in the setting of legal policy. -

Honesty Won't Aid Enemies; CIA INTERROGATION TACTICS

Honesty won’t aid enemies; CIA INTERROGATION TACTICS The National Law Journal (Online) November 26, 2007 Monday Copyright 2007 ALM Media Properties, LLC All Rights Reserved Further duplication without permission is prohibited Length: 949 words Byline: Andrew Kent / Special to The National Law Journal, Special to the national law journal Body The Bush administration maintains that it cannot publicly discuss or even name the harsh interrogation techniques used by the CIA to break the silence of ″high value″ al-Queda captives like Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who devised the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. Recently, Michael Mukasey’s nomination to be attorney general ran into trouble when he declined senators’ requests for his opinion on the legality of waterboarding ? forced inhalation of water, causing choking and asphyxiation ? a technique reportedly used by the CIA on Mohammed and a few others. Mukasey was confirmed, but controversy about the CIA’s methods of interrogating al-Queda leadership, and the official secrecy about them, continues. The Bush administration and its supporters typically offer two reasons why the CIA’s interrogation methods must be secret. Neither is convincing. The principal justification is a variation on the tune the administration has played for years ? opposing us means aiding the enemy. The other justification is protecting CIA interrogators from potential liability. President Bush has repeated that the administration cannot discuss specific methods because ″it doesn’t make any sense to broadcast to the enemy what they ought to prepare for and not prepare for.″ As another official put it, the government cannot ″publicize to the enemy what practices may be on the table and what practices may be off the table. -

Franklin 2010

SAMPLE BALLOT ABSENTEE This is a common ballot, however, BACK OF BALLOT OFFICIAL BALLOT FRANKLIN COUNTY GENERAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT ELECTION some offices will appear only in FRANKLIN COUNTY, ALABAMA NOVEMBER 2, 2010 certain precincts which will apply to your districts. TO VOTE, COMPLETE THE ARROW(S) POINTING TO YOUR CHOICE(S), LIKE THIS: PROPOSED STATEWIDE "Shall the following Amendments be AMENDMENT NUMBER FOUR (4) adopted to the Constitution of Alabama?" Relating to Blount County, proposing an PROPOSED AMENDMENTS WHICH amendment to the Constitution of Alabama FOR ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OF THE FOR PUBLIC SERVICE of 1901, to prohibit any municipality located APPLY TO THE STATE AT LARGE STRAIGHT PARTY VOTING SUPREME COURT, PLACE NO. 1 COMMISSION, PLACE NO. 1 entirely outside of Blount County from (Vote for One) (Vote for One) imposing any municipal ordinance or ALABAMA RHONDA CHAMBERS JAN COOK regulation, including, but not limited to any Democrat Democrat DEMOCRATIC PROPOSED STATEWIDE KELLI WISE TWINKLE ANDRESS CAVANAUGH THESE OFFICES WILL NOT RUN IN ALL PRECINCTS tax, zoning, planning, or sanitation PARTY Republican Republican AMENDMENT NUMBER ONE (1) regulations, and any inspection service in ALABAMA Write-in Write-in Proposing an amendment to the its police jurisdiction located in Blount REPUBLICAN Constitution of Alabama of 1901, to provide County and to provide that a municipality PARTY FOR ASSOCIATE JUSTICE OF THE FOR PUBLIC SERVICE that the provision in Amendment 778, now prohibited from imposing any tax or SUPREME COURT, PLACE NO. 2 COMMISSION, PLACE NO. 2 appearing as Section 269.08 of the Official regulation under this amendment shall not FOR GOVERNOR (Vote for One) (Vote for One) provide any regulatory function or police or (Vote for One) Recompilation of the Constitution of TOM EDWARDS SUSAN PARKER Alabama of 1901, as amended, which fire protection services in its police Democrat Democrat jurisdiction located in Blount County, other RON SPARKS MICHAEL F. -

Open Mcgehrin Drew State of Faith.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES THE STATE OF FAITH: RELIGION AND RACE IN THE 1985 ALABAMA CASE OF WALLACE V. JAFFREE DREW MCGEHRIN Spring 2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Religious Studies and History with interdisciplinary honors in Religious Studies and History Reviewed and approved* by the following: Anne C. Rose Distinguished Professor of History and Religious Studies Thesis Supervisor On-cho Ng Professor of History, Asian Studies, and Philosophy Honors Adviser in Religious Studies Michael Milligan Director of Undergraduate Studies Head of Undergraduate History Intern Program Senior Lecturer in History Second Reader and Honors Adviser in History * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the 1985 Supreme Court decision Wallace v. Jaffree. The case originated in a lawsuit against the State of Alabama by Ishmael Jaffree, an agnostic African American who challenged Governor George Wallace and two Alabama school prayer statutes. The first, enacted in 1981, instructed public schools to allocate time during the school day for a moment of silence for “voluntary prayer.” The second, passed in 1982, instructed teachers to lead their classes in a specific prayer approved by the Alabama State Legislature. Jaffree argued that these laws violated the First Amendment rights of his children, who were students in the Mobile public school system. In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court declared the Alabama statutes unconstitutional under the Establishment Clause. The Court rejected Wallace’s states’ rights argument against the incorporation of the First Amendment. -

Office of the Attorney General the Honorable Mitch Mcconnell

February 3, 2010 The Honorable Mitch McConnell United States Senate Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Senator McConnell: I am writing in reply to your letter of January 26, 2010, inquiring about the decision to charge Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab with federal crimes in connection with the attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 near Detroit on December 25, 2009, rather than detaining him under the law of war. An identical response is being sent to the other Senators who joined in your letter. The decision to charge Mr. Abdulmutallab in federal court, and the methods used to interrogate him, are fully consistent with the long-established and publicly known policies and practices of the Department of Justice, the FBI, and the United States Government as a whole, as implemented for many years by Administrations of both parties. Those policies and practices, which were not criticized when employed by previous Administrations, have been and remain extremely effective in protecting national security. They are among the many powerful weapons this country can and should use to win the war against al-Qaeda. I am confident that, as a result of the hard work of the FBI and our career federal prosecutors, we will be able to successfully prosecute Mr. Abdulmutallab under the federal criminal law. I am equally confident that the decision to address Mr. Abdulmutallab's actions through our criminal justice system has not, and will not, compromise our ability to obtain information needed to detect and prevent future attacks. There are many examples of successful terrorism investigations and prosecutions, both before and after September 11, 2001, in which both of these important objectives have been achieved -- all in a manner consistent with our law and our national security interests. -

Gay Liberation Comes to Dixie—Slowly

Alabama: Commandments, Amendments, and Defendants Patrick R. Cotter Alabama’s 2004 election was a quiet affair. Signs that a presidential campaign was occurring—candidate visits, partisan rallies, hard-hitting tele- vision commercials, or get-out-the-vote efforts—were largely missing from the state. The outcome of Alabama’s U.S. Senate race was a forgone conclu- sion from the beginning of the year. All of the state’s congressmen were easily reelected. Contests for the few state offices up for election in 2004 were generally both invisible and uncompetitive. The only part of the ballot that generated any interest—and even here it was limited—involved a pro- posed amendment to Alabama’s already long state constitution. Alabama’s 2004 election was also a clear Republican victory. Republi- cans George W. Bush and Richard Shelby easily carried the state in the presidential and U.S. Senate elections. The GOP kept it 5-to-2 advantage in Congressional seats. Republicans swept all the contested positions on the state Supreme Court. Alabama’s 2004 election campaign was not the first time the state had experienced a quiet presidential campaign. Nor was it the first in which Republicans did quite well. Both the 1988 and 2000 campaigns were also low-key affairs. Both were also campaigns that the GOP clearly won. These earlier low-key, Republican-winning, presidential campaigns did not significantly alter the state’s partisan politics. Rather, the close partisan balance that has characterized the state since the 1980s continued beyond these elections. (For descriptions of these earlier campaigns and analyses of recent Alabama politics see Cotter 1991; Cotter 2002; Ellington 1999; Cotter and Gordon 1999 and Stanley 2003). -

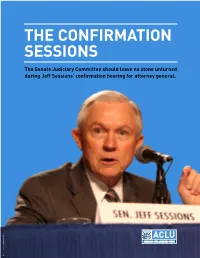

The Confirmation Sessions

THE CONFIRMATION SESSIONS The Senate Judiciary Committee should leave no stone unturned during Jeff Sessions’ confirmation hearing for attorney general. Photo: . Gage Skidmore/Flickr Photo: CONTENTS 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WOULD JEFF SESSIONS CONTINUE THE PUSH FOR POLICE REFORM? 7 WOULD JEFF SESSIONS PROTECT VOTING RIGHTS? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS PROVIDE DUE PROCESS TO IMMIGRANTS 9 AS WELL AS PREVENT THE STATES FROM ENFORCING FEDERAL IMMIGRATION LAW? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS WORK TO REFORM THE POLICIES OF MASS 11 INCARCERATION? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS RESPECT RELIGIOUS LIBERTY, ENSURE 13 THAT RELIGIOUS DISCRIMINATION DOES NOT INFECT U.S. LAWS, AND PROTECT AMERICAN MUSLIMS FROM RELIGIOUS DISCRIMINATION? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS CONTINUE THE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT’S FIGHT 15 FOR LGBT EQUALITY? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS PROTECT VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 16 AND SEXUAL ASSAULT? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS PROTECT U.S. CITIZENS FROM MASS 17 SURVEILLANCE AND FIGHT TO KEEP THEIR SENSITIVE DATA SAFE? 18 WOULD SESSIONS FOLLOW THE LAW ON TORTURE? WOULD JEFF SESSIONS ENFORCE FEDERAL LAW TO PROTECT 19 ABORTION CLINICS? 20 CONCLUSION 21 ENDNOTES 2 THE CONFIRMATION SESSIONS ore than thirty years ago, Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, President-elect Donald Trump’s pick M for Attorney General, was in a similar situation as he will be on January 10 when he goes before the Senate Judiciary Committee for his confirmation hearing. Tapped by President Ronald Reagan for a federal judgeship in 1986, Sessions sat before the very same committee for his previous confirmation hearing. Things did not go well. Witnesses accused Sessions, then the U.S. attorney for the southern district of Alabama, of repeat- edly making racially insensitive and racist remarks. -

Lieutenant Governors: Significant and Visible by Julia Hurst

HEADER RIGHT Lieutenant Governors: Significant and Visible By Julia Hurst Forty-five states now have an officeholder using the title “lieutenant governor.” The experience and profile of the candidates for the office have grown for two years, and that trend continues in the 2006 elections. The duties of the office are also increasing:USA Today newspaper reported in August 2005 that the office of lieutenant governor is a significant, visible and often controversial office. As the office gains attention, future trends indicate state officials will examine the most effective uses of the office. Introduction Likewise, Alabama and South Carolina may have In the November 2005 elections, New Jersey voters showdowns of famous political families within the changed the state constitution creating an office of states through the office of lieutenant governor. In lieutenant governor. The first New Jersey lieutenant Alabama, George Wallace Jr., son of an Alabama governor will be elected on a ticket with the governor governor, is expected to face Jim Folsom Jr., son in 2009. Forty-three states have a statewide elected of a two-term Alabama governor, for election to lieutenant governor. In Tennessee and West Virginia, the office of lieutenant governor. In South Carolina, the Senate president is first in line of gubernatorial incumbent Lt. Gov. Andre Bauer is being challenged succession and both officeholders are statutorily in a primary by Mike Campbell, son of the late and empowered to use the title “lieutenant governor” in former Gov. Carroll Campbell. In addition, Michael recognition of that vital function. In Arizona, Ore- Hollings, son of South Carolina U.S. -

Aspiring to a Model of the Engaged Judge

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2019 Aspiring To A Model of the Engaged Judge Ellen Yaroshefsky Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ellen Yaroshefsky, Aspiring To A Model of the Engaged Judge, 74 N.Y.U. Ann. Surv. Am. L. 393 (2019) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/1251 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASPIRING TO A MODEL OF THE ENGAGED JUDGE ELLEN YAROSHEFSKY* In 1967, within months of his appointment by President Lyn- don Johnson to the Federal Bench in Detroit, Judge Damon Keith, [a] rookie judge and an African American . faced contro- versy almost immediately when, in an unusual confluence of circumstance, four divisive cases landed on his docket-all of which concerned hidden discriminatory practices that were deeply woven into housing, education, employment, and po- lice institutions. Keith shook the nation as he challenged the status quo and faced off against angry crowds, the KKK, corpo- rate America, and even a sitting U.S. President.' In 1970, Judge Keith ordered citywide busing in Pontiac, Mich- igan, to help integrate the city's schools-a ruling that prompted death threats against him and intense resistance by some white par- ents.