Bottles on the Border

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunrise Beverage 2021 Craft Soda Price Guide Office 800.875.0205

SUNRISE BEVERAGE 2021 CRAFT SODA PRICE GUIDE OFFICE 800.875.0205 Donnie Shinn Sales Mgr 704.310.1510 Ed Saul Mgr 336.596.5846 BUY 20 CASES GET $1 OFF PER CASE Email to:[email protected] SODA PRICE QUANTITY Boylan Root Beer 24.95 Boylan Diet Root Beer 24.95 Boylan Black Cherry 24.95 Boylan Diet Black Cherry 24.95 Boylan Ginger Ale 24.95 Boylan Diet Ginger Ale 24.95 Boylan Creme 24.95 Boylan Diet Creme 24.95 Boylan Birch 24.95 Boylan Creamy Red Birch 24.95 Boylan Cola 24.95 Boylan Diet Cola 24.95 Boylan Orange 24.95 Boylan Grape 24.95 Boylan Sparkling Lemonade 24.95 Boylan Shirley Temple 24.95 Boylan Original Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Raspberry Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Lime Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Lemon Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Heritage Tonic 10oz 29.95 Uncle Scott’s Root Beer 28.95 Virgil’s Root Beer 26.95 Virgil’s Black Cherry 26.95 Virgil’s Vanilla Cream 26.95 Virgil’s Orange 26.95 Flying Cauldron Butterscotch Beer 26.95 Bavarian Nutmeg Root Beer 16.9oz 39.95 Reed’s Original Ginger Brew 26.95 Reed’s Extra Ginger Brew 26.95 Reed’s Zero Extra Ginger Brew 26.95 Reed’s Strongest Ginger Brew 26.95 Virgil’s Zero Root Beer Cans 17.25 Virgil’s Zero Black Cherry Cans 17.25 Virgil’s Zero Vanilla Cream Cans 17.25 Virgil’s Zero Cola Cans 17.25 Reed’s Extra Cans 26.95 Reed’s Zero Extra Cans 26.95 Reed’s Real Ginger Ale Cans 16.95 Reed’s Zero Ginger Ale Cans 16.95 Maine Root Mexican Cola 28.95 Maine Root Lemon Lime 28.95 Maine Root Root Beer 28.95 Maine Root Sarsaparilla 28.95 Maine Root Mandarin Orange 28.95 Maine Root Spicy Ginger Beer 28.95 Maine Root Blueberry 28.95 Maine Root Lemonade 12ct 19.95 Blenheim Regular Ginger Ale 28.95 Blenheim Hot Ginger Ale 28.95 Blenheim Diet Ginger Ale 28.95 Cock & Bull Ginger Beer 24.95 Cock & Bull Apple Ginger Beer 24.95 Double Cola 24.95 Sunkist Orange 24.95 Vernor’s Ginger Ale 24.95 Red Rock Ginger Ale 24.95 Cheerwine 24.95 Diet Cheerwine 24.95 Sundrop 24.95 RC Cola 24.95 Nehi Grape 24.95 Nehi Orange 24.95 Nehi Peach 24.95 A&W Root Beer 24.95 Dr. -

Bottles on the Border: the History and Bottles of the Soft Drink Industry In

Bottles on the Border: The History and Bottles of the Soft Drink Industry in El Paso, Texas, 1881-2000 © Bill Lockhart 2010 [Revised Edition – Originally Published Online in 2000] Chapter 5d Chapter 5d Later Empire Companies, Part II, and Duffy’s Draft Beverages Grapette Bottling Company (1941-1969) History Grapette was a relative latecomer to the El Paso bottling industry, although the company began shortly after franchises were first offered by the Grapette Company of Camden, Arkansas, in 1940. The founder of Grapette, Benjamin T. Fooks, originally opened a service station in Camden, Arkansas, but had left the business to begin a bottling plant by 1926. He expanded over the next few years and experimented with flavors including a grape drink. He purchased the registered trademarks, Grapette, Lemonette, and Orangette from Rube Goldstein in 1940 and officially began marketing Grapette in the Spring of that year as the B.T. Fooks Mfg. Co. In 1946, he renamed the business the Grapette Co. He sold the company in 1972 to the Rheingold Corp., a group that became the victim of a hostile takeover by PepsiCo in 1975. Pepsi sold the Grapette line to Monarch in 1977, and the brand was discontinued in the U.S. The drink is still available overseas in 1998 (Magnum 1998). The Grapette Bottling Co. opened its doors in El Paso in 1941, during the World War II sugar rationing period and survived until 1969. In its earliest days, Grapette actually bottled Seven-Up for A.L. Randle who then distributed the product from the Seven-Up Bottling Company next door. -

Box O' Sandwiches

Name ___________________________________________________________ 300 Ren Center , Ste 1304 Page of (Renaissance Center) Company _________________________________________________________ Address __________________________________________________________ (313) 566-0028 (313) 567-6527 City ___________________________ Phone ____________________________ Fax your order, then call to confirm your order. Fax your order ahead for pick-up. No need to wait in line — go right to the register. Desired date __________ Desired time ________ am / pm PICK-UP or DELIVERY Order online at * Payment: Cash Credit (please have credit card info ready when calling to confirm) *Delivery varies by location, call your local shop for more info. Potbelly.com ORIGINALS SKINNYS Drinks Shakes /Malts /Smoothies Turkey Breast CANNED SODA LOW_FAT A Wreck® How many of FLAVOR ShAKE MALT Circle your choice Less meat & cheese Coke Diet SmoothIE 1 Italian on“Thin-Cut” bread 2 each sandwich? Box O’ Sandwiches Chocolate Roast Beef with 25% less fat REGULAR OR Wheat BOTTLED DRINKS of Box below Meatball than Originals 20oz Coke Diet Chicken Salad Strawberry T-K-Y TURKEY BREAST ______R _____ W Smoked Ham 20oz Coke Zero Mushroom Melt ® Tuna Salad A WRECK ______R _____ W Vanilla Hammie 20oz Sprite Vegetarian italian ______R _____ W 500ml Crystal Geyser Water Pizza Sandwich Banana Grilled Chicken ROAST BEEF ______R _____ W 750ml Crystal Geyser Water MeatbaLL ______R _____ W Boylan Black Cherry Oreo® FULL BELLY CHICKEN SALAD ______R _____ W If you ordered IBC Cream Soda Sandwich, Deli -

Symbols & Indies Planogram 1/1.25M England & Wales

SYMBOLS & INDIES PLANOGRAM 1/1.25M ENGLAND & WALES DRINK NOW SYMBOLS & INDIES PLANOGRAM 1/1.25M ENGLAND & WALES DRINK NOW SYMBOLS & INDIES PLANOGRAM 1/1.25M ENGLAND & WALES DRINK NOW SHELF SHELF 11 SHELF SHELF 22 SHELF SHELF 33 SHELF SHELF 44 SHELF SHELF 55 Shelf 1 Shelf 2 Shelf 3 Shelf 4 Shelf 5 FantaShelf 1Orange Pm 65p 330ml DrShelf Pepper 2 Drink Pm 1.09 / 2 For 2.00 500ml FantaShelf 3Orange Pm 1.09 / 2 For 2.00 500ml FantaShelf 4Lemon 500ml SpriteShelf 5Std 500ml IrnFanta Bru OrangeDrink Pm Pm 59p 65p 330ml 330ml MountainDr Pepper Dew Drink Drink Pm Pm1.09 1.19 / 2 For500ml 2.00 500ml FantaFanta FruitOrange Twist Pm Pm 1.09 1.09/2 / 2 For For 2.00 2.00 500ml 500ml FantaFanta ZeroLemon Grape 500ml 500ml IrnSprite Bru StdDrink 500ml Pm 99p 500ml DrIrn PepperBru Drink Std Pm Pm 59p 65p 330ml 330ml CocaMountain Cola Dew Std PmDrink 1.25 Pm 500ml 1.19 500ml DietFanta Coke Fruit Std Twist Pm Pm 1.09 1.09/2 / 2 For For 2.00 2.00 500ml 500ml PepsiFanta MaxZero Std Grape Nas 500mlPm 1.00 / 2 For 1.70 500ml PepsiIrn Bru Max Drink Cherry Pm 99p Nas 500ml Pm 1.00 / 2 F 1.70 500ml CocaDr Pepper Cola StdStd CanPm 65pPm 79p330ml 330ml CocaCoca ColaCola CherryStd Pm Pm 1.25 1.25 500ml 500ml CocaDiet Coke Cola StdZero Pm Std 1.09 Nas / Pm2 For 1.09 2.00 / 2 500ml For 2.00 500ml PepsiPepsi StdMax Pm Std 1.19 Nas 500ml Pm 1.00 / 2 For 1.70 500ml DietPepsi Pepsi Max Std Cherry Pm 1.00Nas Pm/ 2 For1.00 1.70 / 2 F 500ml 1.70 500ml DietCoca Coke Cola Std Std Can Can Pm Pm 69p 79p 330ml 330ml MonsterCoca Cola Energy Cherry Original Pm 1.25 Pm 500ml 1.35 -

SEE HOW THEY RUN Dr

Patrons Mr. and Mrs. Harvey I-l. Acton Mr. William II. Almy Mr. and Mrs. Clyde Baldwin Mr. Clarence Baum Mr. and Mrs. Dan vVi\liams Beckwith Red Mask Players, Inc. Mrs. A. J. Boink Dr. and Mrs. T. H. Brasmer Mr. and Mrs. Frank E. Burroughs Presents Mr. and Mrs. Shirley Catlett Mr. and Mrs. Lane Clark SEE HOW THEY RUN Dr. and Mrs. Harlan English Miss Willa Freeland A Farce in Three Acts Mr. and Mrs. Sid Giles Mr. and Mrs. Merv Gritten by Philip Kin9 Miss Starr Gritten Mr. and Mrs. '~Teldon Harby Jean C. Henson By Special Arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. Mr. and Mrs. Floyd E. Hires Miss Emma Hitchens Mr. and Mrs. B. L. Howell Directed by Mrs. Kathryn Randolph Mr. and Mrs. I-Iarold E. Judy '-v[rs.Clara D. McEvoy Mrs. W. C. Oakley Miss Dea Pichon Miss Gertrude Rick Mrs. E. Strawbridge Miss Gloria Thompson Dr. and Mrs. Kenneth L. Toy Mrs. Charles ''''atkins Miss Frances Watkins PALACE THEATER November 18-19, 1959 Mr. and Mrs. J. M. Webster Danville, Illinois 8:15 P.M. LUXOR An Eating Place of Distinction VISIT THE EGYPTIAN ROOM Opposite Ltlxo,' Motel on East Main Phone HI 6-9745 .. _-----------------_ ... Prepare Your House for Spring NEW WALLPAPER PATTERNS AND PRINTS Vermilion County InSURance Agency In Decorator's Colors INSURANCE OF ALL KINDS WOODBURY BOOK COMPANY 125 NoRTh VeRmilion StreeT Phone HI 6·9158 Adams Building Danville, IllinoiS Beneath the Grease Paint Sponsorships BETTY SUE KRIEDLER (Ida, a Maid)-Fresh from her success in the Red E. -

Collinsville Show Well Attended From: Mike Elling, Sharon, TN Desoto, MO, Shows a Large Picture of a Among the Celebrities Seen Was Mr

4 Winter 2003 Bottles and Extras Collinsville Show Well Attended From: Mike Elling, Sharon, TN DeSoto, MO, shows a large picture of a Among the celebrities seen was Mr. Bill soda bottle, 2 drink glasses, and an ice bowl Meier, of Breese, IL. He is current man- The Metro-East annual Bottle and Jar over a large rectangle. It is mould dated ager of the Excel Bottling Company, and Association Show and Sale, held Sunday, 1955. grandson of the founder. He is the last re- November 3, 2002, was well attended as Delbert Roley, of Stewardson, IL, al- maining bottler of soda products in return- cool, rainy weather brought people in- ways a lucky finder, got a non-Dr Pepper able glass bottles in Illinois. He bottles Ski, doors. The weekend was also scheduled clockface bottle called Berry's Big Time. the highly successful non-caffeine citrus for driving among the brilliant autumn fo- The 10 oz clear glass shows a large drink of the Double Cola Company, and liage surrounding the area. The show is clockface with the hands set at 2:45. It has several other fruit flavor drinks under his held at the Gateway Center in Collinsville, a knurled neck, is in red/white, and is a own brand. He currently uses Nesbitt's Illinois, across the river from St. Louis. An Fairmont, WV, factory of the Owen-Illi- bottles for marketing these. He attended estimated 450 people attended. nois Company dated 1958. Sparkling mint, the show looking for more glass leads in Over 150 tables were available for col- this New Lexington, Ohio bottle was high quantities and had his 3 young chil- lectors to browse. -

DR PEPPER SNAPPLE GROUP ANNUAL REPORT DPS at a Glance

DR PEPPER SNAPPLE GROUP ANNUAL REPORT DPS at a Glance NORTH AMERICA’S LEADING FLAVORED BEVERAGE COMPANY More than 50 brands of juices, teas and carbonated soft drinks with a heritage of more than 200 years NINE OF OUR 12 LEADING BRANDS ARE NO. 1 IN THEIR FLAVOR CATEGORIES Named Company of the Year in 2010 by Beverage World magazine CEO LARRY D. YOUNG NAMED 2010 BEVERAGE EXECUTIVE OF THE YEAR BY BEVERAGE INDUSTRY MAGAZINE OUR VISION: Be the Best Beverage Business in the Americas STOCK PRICE PERFORMANCE PRIMARY SOURCES & USES OF CASH VS. S&P 500 TWO-YEAR CUMULATIVE TOTAL ’09–’10 JAN ’10 MAR JUN SEP DEC ’10 $3.4B $3.3B 40% DPS Pepsi/Coke 30% Share Repurchases S&P Licensing Agreements 20% Dividends Net Repayment 10% of Credit Facility Operations & Notes 0% Capital Spending -10% SOURCES USES 2010 FINANCIAL SNAPSHOT (MILLIONS, EXCEPT EARNINGS PER SHARE) CONTENTS 2010 $5,636 NET SALES +2% 2009 $5,531 $ 1, 3 21 SEGMENT +1% Letter to Stockholders 1 OPERATING PROFIT $ 1, 310 Build Our Brands 4 $2.40 DILUTED EARNINGS +22% PER SHARE* $1.97 Grow Per Caps 7 Rapid Continuous Improvement 10 *2010 diluted earnings per share (EPS) excludes a loss on early extinguishment of debt and certain tax-related items, which totaled Innovation Spotlight 23 cents per share. 2009 diluted EPS excludes a net gain on certain 12 distribution agreement changes and tax-related items, which totaled 20 cents per share. See page 13 for a detailed reconciliation of the Stockholder Information 12 7 excluded items and the rationale for the exclusion. -

Allergen Information | All Soft Drinks & Minerals

ALLERGEN INFORMATION | ALL SOFT DRINKS & MINERALS **THIS INFORMATION HAS BEEN RECORDED AND LISTED ON SUPPLIER ADVICE** DAYLA WILL ACCEPT NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR INACCURATE INFORMATION RECEIVED Cereals containing GLUTEN Nuts Product Description Type Pack ABV % Size Wheat Rye Barley Oats Spelt Kamut Almonds Hazelnut Walnut Cashews Pecan Brazil Pistaccio Macadamia Egg Crustacean Lupin Sulphites >10ppm Celery Peanuts Milk Fish Soya Beans Mollusc Mustard Sesame Seeds Appletiser 24x275ml Case Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Cox's Apple Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Cranberry&Orange Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG E'flower CorDial 6x500ml Minerals Case 0 500ml BG E'flower Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Ginger&Lemongrass Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Ginger&Lemongrass Sprkl SW 12X275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Pomegranate&E'flower Sprkl 12X275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Strawberry CorDial 6x500ml Minerals Case 0 500ml Big Tom Rich & Spicy Minerals Case 0 250ml √ Bottlegreen Cox's Apple Presse 275ml NRB Minerals Case 0 275ml Bottlegreen ElDerflower Presse 275ml NRB Minerals Case 0 275ml Britvic 100 Apple 24x250ml Case Minerals Case 0 250ml Britvic 100 Orange 24x250ml Case Minerals Case 0 250ml Britvic 55 Apple 24x275ml Case Minerals Case 0 275ml Britvic 55 Orange 24x275ml Case Minerals Case 0 275ml Britvic Bitter Lemon 24x125ml Case Minerals Case 0 125ml Britvic Blackcurrant CorDial 12x1l Case Minerals Case 0 1l Britvic Cranberry Juice 24x160ml Case Minerals Case 0 160ml Britvic Ginger Ale 24x125ml Case Minerals Case -

Island Oasis Drink Guide

Frozen Drink Guide “The World’s Finest Frozen DrinkTM” Island Oasis, the leader in the frozen beverage industry, provides outstanding customer service, 24 hour response to all technical service issues and the most innovative and reliable equipment for frozen and “rocks” drinks. Generic and Customized POS such as banners, posters, table tents and menus are available to all customers. Storage & Handling: Store our products frozen for up to two years. Keep refrigerated after thawing. Refrigerated Shelf Life: Unopened: 60 days Opened: 21 days Dairy: 1 yr frozen, 15 days refrigerated Contact Us: We care about your business. Call us today at 1-800-999-5674 or visit our web site at www.islandoasis.com. Classic Cocktails Alcoholic Strawberry Toasted Blue Margarita Daiquiri Almond 4oz Margarita or Sour 4oz Strawberry 3.5oz Ice Cream 1oz Tequila 1.25oz Rum .75oz Amaretto .5oz Blue Curacao .75oz Coffee Liqueur Piña Colada Tropicolada 4oz Piña Colada Strawberry 2oz Piña Colada 1.25oz Dark Rum Shortcake 1oz Banana 4oz Strawberry 1oz Mango Margarita 1.25oz Amaretto 1.25oz Coconut Rum 4oz Margarita or Sour Mix Bushwacker Banana 1.25oz Tequila 3oz Piña Colada Daiquiri 1oz Ice Cream 4oz Banana Mudslide .75oz Coffee Liqueur 1.25oz Rum 3.5oz Ice Cream .75oz Rum .5oz Vodka .5oz Irish Cream .5oz Coffee Liqueur Smoothies Non-Alcoholic Strawberry Mango Colada Tropicolada Smoothie 3oz Piña Colada 1oz Mango 5oz Strawberry 2oz Mango 3oz Piña Colada 1oz Banana Strawberries Kookie Monster n’ Cream 5oz Ice Cream Blended Mocha 3oz Strawberry 2 Crushed Cookies 3oz Ice -

CPY Document

THE COCA-COLA COMPANY 795 795 Complaint IN THE MA TIER OF THE COCA-COLA COMPANY FINAL ORDER, OPINION, ETC., IN REGARD TO ALLEGED VIOLATION OF SEC. 7 OF THE CLAYTON ACT AND SEC. 5 OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION ACT Docket 9207. Complaint, July 15, 1986--Final Order, June 13, 1994 This final order requires Coca-Cola, for ten years, to obtain Commission approval before acquiring any part of the stock or interest in any company that manufactures or sells branded concentrate, syrup, or carbonated soft drinks in the United States. Appearances For the Commission: Joseph S. Brownman, Ronald Rowe, Mary Lou Steptoe and Steven J. Rurka. For the respondent: Gordon Spivack and Wendy Addiss, Coudert Brothers, New York, N.Y. 798 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION DECISIONS Initial Decision 117F.T.C. INITIAL DECISION BY LEWIS F. PARKER, ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE NOVEMBER 30, 1990 I. INTRODUCTION The Commission's complaint in this case issued on July 15, 1986 and it charged that The Coca-Cola Company ("Coca-Cola") had entered into an agreement to purchase 100 percent of the issued and outstanding shares of the capital stock of DP Holdings, Inc. ("DP Holdings") which, in tum, owned all of the shares of capital stock of Dr Pepper Company ("Dr Pepper"). The complaint alleged that Coca-Cola and Dr Pepper were direct competitors in the carbonated soft drink industry and that the effect of the acquisition, if consummated, may be substantially to lessen competition in relevant product markets in relevant sections of the country in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. -

PEPSI BEVERAGE 140 Wygant Road Horseheads,NY,14845 ATTN: TOM MURPHY 607-349-6048 Email: [email protected] Minimumselli WATER: Size Pack Unit Cost Elem Middle H.S

BC Specification Group 1North Loder Ave. Endicott, NY, 13760 Phone - 607-766-3926 Fax - 607-754-0214 Email: [email protected] Vending Bid July 1, 2020 - June 30, 2023 VENDOR: PEPSI BEVERAGE 140 Wygant Road Horseheads,NY,14845 ATTN: TOM MURPHY 607-349-6048 email: [email protected] MinimumSelli WATER: Size Pack Unit Cost Elem Middle H.S. ng Price Aquafina 20 oz. 24 $0.40 x x x $1.25 Aquafina 16.9 oz. 24 $0.24 x x x $1.00 Life Water 20 oz. 24 $1.00 x x x $2.00 100% JUICES Tropicana Apple 10oz. 24 $0.69 x x $1.50 Tropicana Orange Juice 10oz. 24 $0.69 x x $1.50 Tropicana Ruby Red Grapefruit 10oz. 24 $0.69 x x $1.50 Tropicana Ruby Red Grapefruit 12oz. 12 $1.14 x x $2.00 Tropicana PP OJ no pulp 12oz. 12 $1.14 x x $2.00 Tropicana PP OJ + Calcium 12oz. 12 $1.14 x x $2.00 Tropicana OJ Some Pulp 12oz. 12 $1.14 x x $2.00 Tropicana Apple 12oz. 12 $1.14 x x $2.00 Tropicana Grape 12 oz. 12 $1.14 x x $2.00 100% DILUTEN WITH WATER WITH OR WITHOUT CARBONATION AND NO SWEETNER Bubly (all flavors) 12oz. 24 $0.41 x x $1.00 Bubly (all flavors) 16oz. 12 $0.41 $1.00 Schweppes Seltzer (all flavors) 12oz. 24 $0.62 x x $1.25 CARBONATED FLAVORED WATER Bubly (all flavors) 12oz. 24 $0.41 x $1.00 Bubly (all flavors) 16oz. -

Soda Handbook

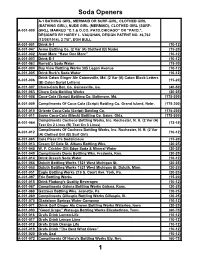

Soda Openers A-1 BATHING GIRL, MERMAID OR SURF-GIRL, CLOTHED GIRL (BATHING GIRL), NUDE GIRL (MERMAID), CLOTHED GIRL (SURF- A-001-000 GIRL), MARKED “C.T.& O.CO. PATD.CHICAGO” OR “PATD.”, DESIGNED BY HARRY L. VAUGHAN, DESIGN PATENT NO. 46,762 (12/08/1914), 2 7/8”, DON BULL A-001-001 Drink A-1 (10-12) A-001-047 Acme Bottling Co. (2 Var (A) Clothed (B) Nude) (15-20) A-001-002 Avon More “Have One More” (10-12) A-001-003 Drink B-1 (10-12) A-001-062 Barrett's Soda Water (15-20) A-001-004 Bay View Bottling Works 305 Logan Avenue (10-12) A-001-005 Drink Burk's Soda Water (10-12) Drink Caton Ginger Ale Catonsville, Md. (2 Var (A) Caton Block Letters A-001-006 (15-20) (B) Caton Script Letters) A-001-007 Chero-Cola Bot. Co. Gainesville, Ga. (40-50) A-001-063 Chero Cola Bottling Works (20-25) A-001-008 Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Baltimore, Md. (175-200) A-001-009 Compliments Of Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Grand Island, Nebr. (175-200) A-001-010 Oriente Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. (175-200) A-001-011 Sayre Coca-Cola (Block) Bottling Co. Sayre, Okla. (175-200) Compliments Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var (A) A-001-064 (12-15) Text On 2 Lines (B) Text On 3 Lines) Compliments Of Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var A-001-012 (10-12) (A) Clothed Girl (B) Surf Girl) A-001-065 Cola Pleez It's Sodalicious (15-20) A-001-013 Cream Of Cola St.