Tusayan Ranger District Travel Management Project Environmental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunrise Beverage 2021 Craft Soda Price Guide Office 800.875.0205

SUNRISE BEVERAGE 2021 CRAFT SODA PRICE GUIDE OFFICE 800.875.0205 Donnie Shinn Sales Mgr 704.310.1510 Ed Saul Mgr 336.596.5846 BUY 20 CASES GET $1 OFF PER CASE Email to:[email protected] SODA PRICE QUANTITY Boylan Root Beer 24.95 Boylan Diet Root Beer 24.95 Boylan Black Cherry 24.95 Boylan Diet Black Cherry 24.95 Boylan Ginger Ale 24.95 Boylan Diet Ginger Ale 24.95 Boylan Creme 24.95 Boylan Diet Creme 24.95 Boylan Birch 24.95 Boylan Creamy Red Birch 24.95 Boylan Cola 24.95 Boylan Diet Cola 24.95 Boylan Orange 24.95 Boylan Grape 24.95 Boylan Sparkling Lemonade 24.95 Boylan Shirley Temple 24.95 Boylan Original Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Raspberry Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Lime Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Lemon Seltzer 24.95 Boylan Heritage Tonic 10oz 29.95 Uncle Scott’s Root Beer 28.95 Virgil’s Root Beer 26.95 Virgil’s Black Cherry 26.95 Virgil’s Vanilla Cream 26.95 Virgil’s Orange 26.95 Flying Cauldron Butterscotch Beer 26.95 Bavarian Nutmeg Root Beer 16.9oz 39.95 Reed’s Original Ginger Brew 26.95 Reed’s Extra Ginger Brew 26.95 Reed’s Zero Extra Ginger Brew 26.95 Reed’s Strongest Ginger Brew 26.95 Virgil’s Zero Root Beer Cans 17.25 Virgil’s Zero Black Cherry Cans 17.25 Virgil’s Zero Vanilla Cream Cans 17.25 Virgil’s Zero Cola Cans 17.25 Reed’s Extra Cans 26.95 Reed’s Zero Extra Cans 26.95 Reed’s Real Ginger Ale Cans 16.95 Reed’s Zero Ginger Ale Cans 16.95 Maine Root Mexican Cola 28.95 Maine Root Lemon Lime 28.95 Maine Root Root Beer 28.95 Maine Root Sarsaparilla 28.95 Maine Root Mandarin Orange 28.95 Maine Root Spicy Ginger Beer 28.95 Maine Root Blueberry 28.95 Maine Root Lemonade 12ct 19.95 Blenheim Regular Ginger Ale 28.95 Blenheim Hot Ginger Ale 28.95 Blenheim Diet Ginger Ale 28.95 Cock & Bull Ginger Beer 24.95 Cock & Bull Apple Ginger Beer 24.95 Double Cola 24.95 Sunkist Orange 24.95 Vernor’s Ginger Ale 24.95 Red Rock Ginger Ale 24.95 Cheerwine 24.95 Diet Cheerwine 24.95 Sundrop 24.95 RC Cola 24.95 Nehi Grape 24.95 Nehi Orange 24.95 Nehi Peach 24.95 A&W Root Beer 24.95 Dr. -

Box O' Sandwiches

Name ___________________________________________________________ 300 Ren Center , Ste 1304 Page of (Renaissance Center) Company _________________________________________________________ Address __________________________________________________________ (313) 566-0028 (313) 567-6527 City ___________________________ Phone ____________________________ Fax your order, then call to confirm your order. Fax your order ahead for pick-up. No need to wait in line — go right to the register. Desired date __________ Desired time ________ am / pm PICK-UP or DELIVERY Order online at * Payment: Cash Credit (please have credit card info ready when calling to confirm) *Delivery varies by location, call your local shop for more info. Potbelly.com ORIGINALS SKINNYS Drinks Shakes /Malts /Smoothies Turkey Breast CANNED SODA LOW_FAT A Wreck® How many of FLAVOR ShAKE MALT Circle your choice Less meat & cheese Coke Diet SmoothIE 1 Italian on“Thin-Cut” bread 2 each sandwich? Box O’ Sandwiches Chocolate Roast Beef with 25% less fat REGULAR OR Wheat BOTTLED DRINKS of Box below Meatball than Originals 20oz Coke Diet Chicken Salad Strawberry T-K-Y TURKEY BREAST ______R _____ W Smoked Ham 20oz Coke Zero Mushroom Melt ® Tuna Salad A WRECK ______R _____ W Vanilla Hammie 20oz Sprite Vegetarian italian ______R _____ W 500ml Crystal Geyser Water Pizza Sandwich Banana Grilled Chicken ROAST BEEF ______R _____ W 750ml Crystal Geyser Water MeatbaLL ______R _____ W Boylan Black Cherry Oreo® FULL BELLY CHICKEN SALAD ______R _____ W If you ordered IBC Cream Soda Sandwich, Deli -

Symbols & Indies Planogram 1/1.25M England & Wales

SYMBOLS & INDIES PLANOGRAM 1/1.25M ENGLAND & WALES DRINK NOW SYMBOLS & INDIES PLANOGRAM 1/1.25M ENGLAND & WALES DRINK NOW SYMBOLS & INDIES PLANOGRAM 1/1.25M ENGLAND & WALES DRINK NOW SHELF SHELF 11 SHELF SHELF 22 SHELF SHELF 33 SHELF SHELF 44 SHELF SHELF 55 Shelf 1 Shelf 2 Shelf 3 Shelf 4 Shelf 5 FantaShelf 1Orange Pm 65p 330ml DrShelf Pepper 2 Drink Pm 1.09 / 2 For 2.00 500ml FantaShelf 3Orange Pm 1.09 / 2 For 2.00 500ml FantaShelf 4Lemon 500ml SpriteShelf 5Std 500ml IrnFanta Bru OrangeDrink Pm Pm 59p 65p 330ml 330ml MountainDr Pepper Dew Drink Drink Pm Pm1.09 1.19 / 2 For500ml 2.00 500ml FantaFanta FruitOrange Twist Pm Pm 1.09 1.09/2 / 2 For For 2.00 2.00 500ml 500ml FantaFanta ZeroLemon Grape 500ml 500ml IrnSprite Bru StdDrink 500ml Pm 99p 500ml DrIrn PepperBru Drink Std Pm Pm 59p 65p 330ml 330ml CocaMountain Cola Dew Std PmDrink 1.25 Pm 500ml 1.19 500ml DietFanta Coke Fruit Std Twist Pm Pm 1.09 1.09/2 / 2 For For 2.00 2.00 500ml 500ml PepsiFanta MaxZero Std Grape Nas 500mlPm 1.00 / 2 For 1.70 500ml PepsiIrn Bru Max Drink Cherry Pm 99p Nas 500ml Pm 1.00 / 2 F 1.70 500ml CocaDr Pepper Cola StdStd CanPm 65pPm 79p330ml 330ml CocaCoca ColaCola CherryStd Pm Pm 1.25 1.25 500ml 500ml CocaDiet Coke Cola StdZero Pm Std 1.09 Nas / Pm2 For 1.09 2.00 / 2 500ml For 2.00 500ml PepsiPepsi StdMax Pm Std 1.19 Nas 500ml Pm 1.00 / 2 For 1.70 500ml DietPepsi Pepsi Max Std Cherry Pm 1.00Nas Pm/ 2 For1.00 1.70 / 2 F 500ml 1.70 500ml DietCoca Coke Cola Std Std Can Can Pm Pm 69p 79p 330ml 330ml MonsterCoca Cola Energy Cherry Original Pm 1.25 Pm 500ml 1.35 -

DR PEPPER SNAPPLE GROUP ANNUAL REPORT DPS at a Glance

DR PEPPER SNAPPLE GROUP ANNUAL REPORT DPS at a Glance NORTH AMERICA’S LEADING FLAVORED BEVERAGE COMPANY More than 50 brands of juices, teas and carbonated soft drinks with a heritage of more than 200 years NINE OF OUR 12 LEADING BRANDS ARE NO. 1 IN THEIR FLAVOR CATEGORIES Named Company of the Year in 2010 by Beverage World magazine CEO LARRY D. YOUNG NAMED 2010 BEVERAGE EXECUTIVE OF THE YEAR BY BEVERAGE INDUSTRY MAGAZINE OUR VISION: Be the Best Beverage Business in the Americas STOCK PRICE PERFORMANCE PRIMARY SOURCES & USES OF CASH VS. S&P 500 TWO-YEAR CUMULATIVE TOTAL ’09–’10 JAN ’10 MAR JUN SEP DEC ’10 $3.4B $3.3B 40% DPS Pepsi/Coke 30% Share Repurchases S&P Licensing Agreements 20% Dividends Net Repayment 10% of Credit Facility Operations & Notes 0% Capital Spending -10% SOURCES USES 2010 FINANCIAL SNAPSHOT (MILLIONS, EXCEPT EARNINGS PER SHARE) CONTENTS 2010 $5,636 NET SALES +2% 2009 $5,531 $ 1, 3 21 SEGMENT +1% Letter to Stockholders 1 OPERATING PROFIT $ 1, 310 Build Our Brands 4 $2.40 DILUTED EARNINGS +22% PER SHARE* $1.97 Grow Per Caps 7 Rapid Continuous Improvement 10 *2010 diluted earnings per share (EPS) excludes a loss on early extinguishment of debt and certain tax-related items, which totaled Innovation Spotlight 23 cents per share. 2009 diluted EPS excludes a net gain on certain 12 distribution agreement changes and tax-related items, which totaled 20 cents per share. See page 13 for a detailed reconciliation of the Stockholder Information 12 7 excluded items and the rationale for the exclusion. -

Island Oasis Drink Guide

Frozen Drink Guide “The World’s Finest Frozen DrinkTM” Island Oasis, the leader in the frozen beverage industry, provides outstanding customer service, 24 hour response to all technical service issues and the most innovative and reliable equipment for frozen and “rocks” drinks. Generic and Customized POS such as banners, posters, table tents and menus are available to all customers. Storage & Handling: Store our products frozen for up to two years. Keep refrigerated after thawing. Refrigerated Shelf Life: Unopened: 60 days Opened: 21 days Dairy: 1 yr frozen, 15 days refrigerated Contact Us: We care about your business. Call us today at 1-800-999-5674 or visit our web site at www.islandoasis.com. Classic Cocktails Alcoholic Strawberry Toasted Blue Margarita Daiquiri Almond 4oz Margarita or Sour 4oz Strawberry 3.5oz Ice Cream 1oz Tequila 1.25oz Rum .75oz Amaretto .5oz Blue Curacao .75oz Coffee Liqueur Piña Colada Tropicolada 4oz Piña Colada Strawberry 2oz Piña Colada 1.25oz Dark Rum Shortcake 1oz Banana 4oz Strawberry 1oz Mango Margarita 1.25oz Amaretto 1.25oz Coconut Rum 4oz Margarita or Sour Mix Bushwacker Banana 1.25oz Tequila 3oz Piña Colada Daiquiri 1oz Ice Cream 4oz Banana Mudslide .75oz Coffee Liqueur 1.25oz Rum 3.5oz Ice Cream .75oz Rum .5oz Vodka .5oz Irish Cream .5oz Coffee Liqueur Smoothies Non-Alcoholic Strawberry Mango Colada Tropicolada Smoothie 3oz Piña Colada 1oz Mango 5oz Strawberry 2oz Mango 3oz Piña Colada 1oz Banana Strawberries Kookie Monster n’ Cream 5oz Ice Cream Blended Mocha 3oz Strawberry 2 Crushed Cookies 3oz Ice -

CPY Document

THE COCA-COLA COMPANY 795 795 Complaint IN THE MA TIER OF THE COCA-COLA COMPANY FINAL ORDER, OPINION, ETC., IN REGARD TO ALLEGED VIOLATION OF SEC. 7 OF THE CLAYTON ACT AND SEC. 5 OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION ACT Docket 9207. Complaint, July 15, 1986--Final Order, June 13, 1994 This final order requires Coca-Cola, for ten years, to obtain Commission approval before acquiring any part of the stock or interest in any company that manufactures or sells branded concentrate, syrup, or carbonated soft drinks in the United States. Appearances For the Commission: Joseph S. Brownman, Ronald Rowe, Mary Lou Steptoe and Steven J. Rurka. For the respondent: Gordon Spivack and Wendy Addiss, Coudert Brothers, New York, N.Y. 798 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION DECISIONS Initial Decision 117F.T.C. INITIAL DECISION BY LEWIS F. PARKER, ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE NOVEMBER 30, 1990 I. INTRODUCTION The Commission's complaint in this case issued on July 15, 1986 and it charged that The Coca-Cola Company ("Coca-Cola") had entered into an agreement to purchase 100 percent of the issued and outstanding shares of the capital stock of DP Holdings, Inc. ("DP Holdings") which, in tum, owned all of the shares of capital stock of Dr Pepper Company ("Dr Pepper"). The complaint alleged that Coca-Cola and Dr Pepper were direct competitors in the carbonated soft drink industry and that the effect of the acquisition, if consummated, may be substantially to lessen competition in relevant product markets in relevant sections of the country in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. -

PORTFOLIO New York Stock Exchange-DPS Performance Record

PAGE 44 OCTOBER 26, 2012 MARKETWATCH ROCHESTER BUSINESS JOURNAL PORTFOLIO LOCAL STOCK PERFORMANCE A weekly report compiled from the proxy statement and annual report of a publicly held NET PERCENT company with local headquarters or a company with a major division in the area CLOSING CLOSING CHANGE CHANGE ANNUAL PRICE PRICE IN IN P/E EARNINGS DIVIDEND 52 - WEEK 10/22/12 10/19/12PERIOD PERIOD RATIO PER SHARE1 RATE2 HIGH LOW NONE ADT Corp. (NY-ADT) 38.90 37.85 1.05 2.77 22.60 1.72 41.00 34.68 AT&T Inc. (NY-T) 35.26 35.35 -0.09 -0.25 47.00 0.75 1.64 38.58 27.41 Arista Power Inc. (ASPW.OB) 1.62 1.85 -0.23 -12.43 LOSS -0.36 NONE 4.00 0.10 Bank of America Corp. (NY-BAC) 9.55 9.42 0.13 1.38 26.40 0.36 0.04 25.37 18.24 New York Stock Exchange-DPS Bon-Ton Stores Inc. (NAS-BONT) 11.51 12.46 -0.95 -7.62 LOSS -1.88 NONE 14.99 2.23 Based in Plano, Texas, Dr Pepper Snapple Group Inc. is an integrated brand owner, CVS Caremark Corp. (NY-CVS) 46.26 46.90 -0.64 -1.36 16.30 2.80 0.30 49.23 35.09 manufacturer and distributor of non-alcoholic beverages in the United States, Canada and Mexico with a portfolio of flavored, carbonated soft drinks and non-carbonated beverages. Ciber Inc. (NY-CBR) 3.05 3.34 -0.29 -8.68 48.40 -0.16 NONE 4.76 3.01 The latter include ready-to-drink teas, juices, juice drinks and mixers. -

Pepsi Diet Pepsi Dr Pepper Sierra Mist Mountain Dew Orange Crush Fruit Punch Lemonade

Beefed Up! Cheese Fries 9.59 Buffalo Fries 5.95 4 Cheese Toasted Ravioli 5.95 10 pc Homestyle Onion Rings 5.95 Loaded Cheese Fries 9.59 Mozzarella Sticks 5.95 6 pc 7.95 10 pc BEEFED UP! CHEESE FRIES BUFFALO BLEU FRIES Factory Fries 2.95 Add Cheddar Cheese 1.95 Mac & Cheese Wedges 5.95 8 pc Factory Sampler Platter 12.95 Chicago Dog Fries 9.95 Buffalo Bleu Fries 9.59 Southern Comfort Fries 9.59 Fried Pickles 5.95 SOUTHERN COMFORT FRIES Factory Salad 9.59 Hearts of romaine, sweet red onion, roasted red peppers, grilled chicken breast, smoked bacon bits, chopped avocado, topped with crumbled bleu cheese Chicago Chopped Salad 9.59 Finely chopped hearts of romaine, tomato, cucumber, sweet onion, garlic roasted croutons, mozzarella and smoked bacon bits. Add chicken 3.00 Very Berry Almond Salad 7.95 Spring mixed leaves salad with cranberries, sliced almonds and topped with crumbled bleu cheese and balsamic vinaigrette California Cobb Salad 9.59 Romaine lettuce, Grape tomato, Grilled chicken breast, chopped avocado, crumbled bleu cheese, smoked bacon bits and boiled egg Mediterranean Greek Salad 7.95 Romaine lettuce, grape tomato, sweet red onion, cucumbers, black olives, Greekdolmades served with Greek vinaigrette dressing Garden Salad 6.95 Hearts of romaine, tomato, sweet red onion, cucumber, boiled egg and pepperoncini Add chicken 3.00 Caesar Salad 6.95 Hearts of romaine, shaved parmigiano reggiano, garlic roasted croutons, and parmesan cheese Add chicken 3.00 Fresca 6.95 Local Spring mix, Grape tomatoes, sweet red onions, imported shaved parmigiano reggiano with balsamic dressing Meatball Salad 9.59 3 house made meatballs, along side fresh shredded Parmigiano Regiano with an hearty Italian spring mix garden salad Perfect Spinach Salad 6.95 Dressing Choices: House Italian Caesar Balsamic Vinaigrette Raspberry Vinaigrette Ranch Asian Sesame Ginger Creamy Garlic Lemon Vinaigrette Bleu Cheese Greek Vinaigrette No substitutions or modification on slice-thru orders. -

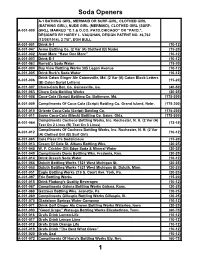

Soda Handbook

Soda Openers A-1 BATHING GIRL, MERMAID OR SURF-GIRL, CLOTHED GIRL (BATHING GIRL), NUDE GIRL (MERMAID), CLOTHED GIRL (SURF- A-001-000 GIRL), MARKED “C.T.& O.CO. PATD.CHICAGO” OR “PATD.”, DESIGNED BY HARRY L. VAUGHAN, DESIGN PATENT NO. 46,762 (12/08/1914), 2 7/8”, DON BULL A-001-001 Drink A-1 (10-12) A-001-047 Acme Bottling Co. (2 Var (A) Clothed (B) Nude) (15-20) A-001-002 Avon More “Have One More” (10-12) A-001-003 Drink B-1 (10-12) A-001-062 Barrett's Soda Water (15-20) A-001-004 Bay View Bottling Works 305 Logan Avenue (10-12) A-001-005 Drink Burk's Soda Water (10-12) Drink Caton Ginger Ale Catonsville, Md. (2 Var (A) Caton Block Letters A-001-006 (15-20) (B) Caton Script Letters) A-001-007 Chero-Cola Bot. Co. Gainesville, Ga. (40-50) A-001-063 Chero Cola Bottling Works (20-25) A-001-008 Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Baltimore, Md. (175-200) A-001-009 Compliments Of Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Grand Island, Nebr. (175-200) A-001-010 Oriente Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. (175-200) A-001-011 Sayre Coca-Cola (Block) Bottling Co. Sayre, Okla. (175-200) Compliments Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var (A) A-001-064 (12-15) Text On 2 Lines (B) Text On 3 Lines) Compliments Of Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var A-001-012 (10-12) (A) Clothed Girl (B) Surf Girl) A-001-065 Cola Pleez It's Sodalicious (15-20) A-001-013 Cream Of Cola St. -

A Comparative Study on Orange Flavoured Soft Drinks with Special Reference to Mirinda, Fanta and Torino in Ramanathapuram District

Vol. 3 No. 2 October 2015 ISSN: 2321 – 4643 3 A COMPARATIVE STUDY ON ORANGE FLAVOURED SOFT DRINKS WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO MIRINDA, FANTA AND TORINO IN RAMANATHAPURAM DISTRICT M.Abbas Malik Associate Professor & Head, Department of Management Studies, Mohamed Sathak Engineering College, Kilakarai – 623 806 Abstract Soft drinks market in India has been grown in size with the entry of the Multi National Corporations. At present soft drink market is one of the most competitive markets in India which spends crores of rupees in advertisement and other promotionary activities. A bottle drink consumers have a wide range of brands at their disposal. It is difficult for a consumer to stick on to a particular brand of flavour unless the consumer satisfaction level is very high. Orange flavoured soft drink is one of the popular segments in soft drink. In India Mirinda and Fanta are the major orange flavoured soft drinks. But in this area under study (Ramanathapuram District) Torino is a local brand is having very good presence and influences. So, researcher wanted to know their present market share of Mirinda, Fanta and Torino. The objectives of the Study are: 1. To estimate the market share of major orange flavoured soft drink brands under the area of study. 2. To study the Socio-economic profile by using orange flavoured drinks. 3. To find the most preferred orange flavour soft drink in the market. 4. To determine the reason for preferring a particular brand of orange flavoured soft drink. 5. To make suggestions based on the findings of the study. -

Bristol-Products.Pdf

Dowser Pure 24/20oz Sport 24/25oz Pure 12/1 LTR Seltzer 24/20oz Dowser Pure 24/16.9oz Aquafina Water 24/20oz 15/1 LTR Aquafina Splash 24/20oz Pepsi Cola Grape / Wild Berry O.N.E. Coconut Water of Bristol 12/16.9oz Guava / Mango / Pineapple / Regular “Your Total Beverage Company” 12/1L Plain SoBe Life Water 12/20oz Pepsi Cola Pomegranate Cherry / Strawberry Kiwi / Pacific Coconut Water of Bristol O Calorie SoBe Life Water Fuji Apple Pear / YumBerry Pom / Black & Blue Berry / Strawberry “Your Total DragonFruit / Acai Raspberry / Blood Orange / Cherimoya Kiwi Beverage Company” Gatorade 24/20oz Fruit Punch / Glacier Freeze/ Lemon Lime / Orange / Fierce Grape / Cool Blue / Riptide Rush G2 Fruit Punch / G2 Grape 15/28oz Lemon Lime / Fruit Punch / Cool Blue / Orange / Frost Glacier Freeze / Frost Glacier Cherry / Fierce Grape / Lime Cucumber / Fierce Strawber- ry / Fierce Blue Cherry / Strawberry Lemonade / Fierce Melon / Fierce Green Apple / Citrus Cooler / Frost Riptide Rush / AM Tropical Man- go / Tangerine / Fierce Fruit Punch & Berry / G2 Fruit Punch / G2 Grape 24/24oz Sportcap Pepsi Fruit Punch / Cool Blue / Lemon Lime Waters 8/64oz Juice Fruit Punch / Orange / Lemon Lime Lipton Teas Every fountain need available including juices Energy Drinks Coffee www.PepsiColaofBristol.com 110 Corporate Drive Southington, CT 06489 Phone (860) 628-8200 Fax (860) 628-0822 www.PepsiColaofBristol.com PRICES EFFECTIVE 1/26/15 24/12oz Can Pure Leaf Mountain Dew AMP Pepsi / Diet Pepsi / CF Pepsi / Diet CF Pepsi / 12/18.5oz Bottles 12/16oz Cans Wild Cherry / Diet Pepsi Lime / Pepsi Throw- Sweet Lemon / Sweet no Lemon / Boost Original / Boost SF / back / Diet Wild Cherry / Pepsi Max / Mtn Dew / Raspberry / Unsweetened No Lem- Boost Grape / Focus Mixed Diet Mtn Dew / Code Red / Mtn Dew Whiteout / Berry / Boost Cherry Sierra Mist / Dt Sierra Mist / Mug Root Beer / on / Peach / Diet Peach / Diet Lem- Diet Mug Root Beer / Dr Pepper / Dt. -

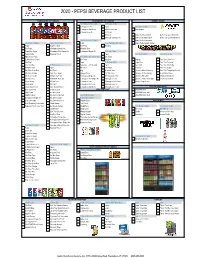

2020 - Pepsi Beverage Product List

2020 - PEPSI BEVERAGE PRODUCT LIST CARBONATED SOFT DRINKS CARBONATED SOFT DRINKS ENERGY DRINKS 10oz Glass Bottles (24pk) 16oz Cans (12pk) Schweppes Tonic Pepsi 16oz Cans (12pk) Schweppes Club Soda Wild Cherry Pepsi Amp Original Schweppes G. Ale Diet Pepsi Mtn.Dew Game Fuel Berry Blast Game Fuel Zero Watermln Schweppes Ginger Ale Game Fuel Original Dew Game Fuel Zero Rasp/Lmnd 12oz PET Bottles (3/8pk) Game Fuel Cherry Burst 20oz Bottles (24pk) 12oz Cans (2/12pk) Pepsi 16oz Aluminum Btl (12pk) Game Fuel Charged Orange Pepsi Mug Root Beer Diet Pepsi Mtn.Dew Diet Pepsi Schweppes Ginger Ale Mountain Dew Pepsi Zero Sugar Schweppes Diet Ginger Ale Schweppes Ginger Ale 1.25 Liter (12pk) Pepsi Vanilla Hawaiian Punch Pepsi 16oz Cans (24pk) 16oz Cans (24pk) Wild Cherry Pepsi 7.5oz Mini Cans 6pk(3/10pk*) Diet Pepsi Dt Wild Cherry Pepsi Diet Pepsi * Mtn.Dew Original Pure Zero Silver Ice Mist Twst Pepsi * 1L Bottles (15pk) Sugar Free Pure Zero Punched Mountain Dew 2L Bottles (8pk) Pepsi Zero - 3/10pk Only Pepsi Zero Carb Pure Zero Mand Org Diet Mtn Dew Pepsi Mtn. Dew * Diet Pepsi Punched Pure Zero Grape Mtn. Dew Code Red Diet Pepsi Mug Mountain Dew Xdurance Kiwi Strawberry Pure Zero Tang/Mng/Guv/Str Mtn. Dew Voltage Pepsi Zero Sugar Orange Crush Diet Mtn. Dew Xdurance Cotton Candy Revolt Killer Grape Mtn.Dew Livewire Wild Cherry Pepsi Schweppes Ginger Ale* Mtn.Dew Code Red Xdurance Blue-Raz Whipped Strawberry Mtn. Dew Zero Dt Wild Cherry Pepsi Schweppes Diet Ginger Ale Schweppes Tonic Xdurance Super Sour Apple Thermo Neon Blast Crush Orange Dt Pepsi Free Schweppes Tonic Schweppes Club Soda Thermo Tropical Fire Crush Grape Mist Twst Schweppes Diet Tonic Schweppes G.