Review of Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consumer Attitude of People Towards Commercial Center with Special Reference to Oberon Mall, Kochi

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-8 Issue-6, March 2020 Consumer Attitude of People towards Commercial Center with Special Reference to Oberon Mall, Kochi Athira K Thampi, Athira V Menon, K G Rajani Abstract: A shopping mall is a building that contains retail stores under one roof. It is the collection or group of different II. OBJECTIVES stores offering various brands, products or services at one ● To know the approaches of people towards the new place.In malls under one roof we can see different consumer generation shopping malls with special reference to Oberon attitudes. But this wasn’t the case before the arrival of mall, people was depending on mom-and-pop stores and margin free to mall, Kochi, Kerala. get their supplementary, and need to visit other stores to get ● To know the effect of new generation malls on several other things like garments , groceries etc. But this was not lifestyle of people. the case when mall was introduced, people was free to purchase ● To know the shift in satisfaction level of customers from one place where we get all the needed things. Nowadays, malls are situated in almost every major city around the world of retail shops with the establishment of shopping malls. which plays a pivot role in today’s environment and we see STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM: consumer with different purchasing behaviour. Shopping mall is considered as the very important factor. Index Terms: Consumers, Consumer attitude,Commercial The main advantage of a mall is each and every product attraction, Feasibility, Merchandise, Purchasing behaviour. -

Travancore Swiss Gardens

https://www.propertywala.com/travancore-swiss-gardens-kochi Travancore Swiss Gardens - Thrikkakara, Kochi Superior Villas meant for independent and open living Travancore Swiss Gardens offers superior villas with amenities and facilities like clubhouse, lush lawns etc.The design of each villa shows a perfect mix and blend of Holistic design approach and classic European touch. Project ID : J469611190 Builder: Travancore Builders Location: Travancore Swiss Garden, Vallathol Padi, Thrikkakara, Kochi - 682032 (Kerala) Completion Date: Jan, 2014 Status: Started Description Travancore Builders holds special pride in launching its most waited project Swiss Gardens. Travancore Builders is a name acclaimed for their master creations. The group always aim at providing projects which assures quality and perfection.The group go ahead with the concept of open living. And so they provide independent villas which best suits open living. Travancore Swiss Gardens spreads over to an area of nearly 9 acres of land. The project offers superior villas with amenities and facilities like clubhouse, lush lawns etc.The design of each villa shows a perfect mix and blend of Holistic design approach and classic European touch.Every villa is equipped with the necessary requirements for modern day life style.Its provision of seamlessly crafted ambiance persuades the fine sensibility of class of people. Amenities Club Swimming Pool Play Courts Kids' Areas Facilities Lift: Home lift of approved make connecting all the three floors. Home Automation: Automated electrical accessories like lights, fans, etc. Using advanced automation system. Security System: Video door phone, surveillance system for common areas. Interior landscaping: Rear side semi courtyard landscaped with various plants, pebbles etc. -

Demographic Factors Influencing the Buying Behaviour of Consumers Toward the Green Products in Kerala

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Demographic Factors influencing the Buying Behaviour of Consumers toward the Green Products in Kerala 1Rahul Ramesh, 2Dr. B. Ramesh 1Research Scholar, Department of Management Studies, Kannur University, Thalaserry Campus, Palayad, Kannur-670661, Kerala, India, 2Professor, Rajagiri School of Social Sciences, Kalamassery, Ernakulam, Kerala, India. Abstract: The state of Kerala well known for its rich flora and fauna, high literacy and high health standards, have also made spectacular strides towards the green movement and has become a topic of discussions and debates in several circles. In this context, it becomes quite imperative to analyse the changing consumers’ perceptions towards Green Products. It will also help the policy makers, entrepreneurs and traders in formulating various strategies to better strive towards ‘Green Living’. A sample of 260 consumers, 52 each from 5 major Shopping Malls in the district of Ernakulam in Kerala was taken for the study. This paper tries to analyse the extent influence of certain demographic factors which influence the buying behaviour of the Green Product consumers in Kerala. Index Terms - Green Products, Demographic Factors, Buying Behaviour, Purchasing Behaviour. I. INTRODUCTION Green products have been assuming more prominence during recent years due to the growing concern all over the world about the rising number of environmental issues consequent upon the dumbing of plastic and other non-degradable materials resulting from the consumption of various products. The ever increasing population and shrinkage of cultivable areas due to the conversion for construction works and other developmental projects have aggravated these issues. -

Department of Industries & Commerce District

Industrial Potential Survey of Ernakulam District GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRIES & COMMERCE DISTRICT INDUSTRIES CENTRE ERNAKULAM POTENTIAL SURVEY REPORT FOR MSME SECTOR Prepared and Published by DISTRICT INDUSTRIES CENTRE KUNNUMPURAM CIVIL STATION ROAD,KAKKANAD,ERNAKULAM PH: 0484-2421432,2421461,FAX – 0484 2421461 E mail- [email protected], [email protected] Web site: www.dic.kerala.gov.in 1 Prepared & Submitted by District Industries Centre,Ernakulam Industrial Potential Survey of Ernakulam District PREFACE An Industrial Potential Survey of Ernakulam District, the industrial capital of Kerala, definitely will be a reflection of the State as a whole. The report is prepared mostly on the basis of available information in different sectors. The survey report reveals the existing industrial scenario of the district and it mainly aims to unveil the potentially disused areas of the industry in Ernakulam. We hope this document will provide guidance for those who need to identify various potential sources/ sectors of industry and thereby can contribute industrial development of the district, and the state. I hereby acknowledge the services rendered by all Managers, Assistant District Industries Officers , Industries Extension Officers ,Statistical Wing and other officers of this office ,for their sincere effort and whole hearted co- operation to make this venture a success within the stipulated time. I am grateful to all the officers of other departments who contributed valuable suggestions and information to prepare this report. General Manager, District Industries Centre, Ernakulam. 2 Prepared & Submitted by District Industries Centre,Ernakulam Industrial Potential Survey of Ernakulam District INDEX Contents Page No Scope & Objectives Methodology Chapter I District at a glance 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Location and extent 1.3 District at a glance 2. -

Evaluation of in Store Attributes Relating to Shopping Malls 1Aarathy K

International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Volume 119 No. 12 2018, 2527-2536 ISSN: 1314-3395 (on-line version) url: http://www.ijpam.eu Special Issue ijpam.eu Evaluation of in Store Attributes Relating to Shopping Malls 1Aarathy K. Sudhakaran and 2A. Anis 1Department of Commerce and Management, Amrita school of Arts and Sciences, Amritapuri Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Kerala, India. [email protected] 2Department of Commerce and Management, Amrita school of Arts and Sciences, Amritapuri Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Kerala, India. [email protected] Abstract Instore attributes constitute a predominant role in determining the consumer shopping experiences. In this era, shopping malls plays a crucial role in the life of a consumer. Due to the growing competition faced by retailers, the importance of evaluating the instore attributes are relevant. This study tries to understand the attributes leading to the consumer shopping experiences. The study uses extended literatures and has used convenience sampling, samples are collected from 250 consumers shopping from the major malls in Kochi. The study tries to bring out the instore facilities used and its impact on consumer shopping experiences. The study tries to project the major determining factors in shopping mall evaluations and the consumers shopping experiences in relation to instore attributes. Key Words: customer experience, instore attributes, customer satisfaction. 2527 International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Special Issue 1. Introduction Now a days shopping centres play a noteworthy part in the way of life of the general population living in the country that had hugely altered the types of spending actions. These days shopping centres are found in every single circle and corner, not only that individuals trust the shopping centres is the relevant destination to swing on. -

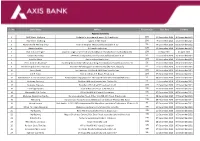

Sr. No. Outlet Name Address Discount Offer Start Date End

Sr. No. Outlet Name Address Discount offer Start Date End date Apparels & Textiles 1 1947 Mens Clothing Vaduthala Jn,naduvath nagar PO,Arookkutty 30% 21 December 2020 20 December 2021 2 1947 Mens Clothing Iyyatil Jn,MG Road 30% 19 December 2020 18 December 2021 3 Abaya World And top shop Near olimughal Masjid,kakkanad,cochin-30 5% 09 December 2020 08 December 2021 4 Action Textiles DH road,Ernakulam 10% 11 December 2020 10 December 2021 5 Club India designer Jawahar nagar,near Bread world,Subhash Chandra bose road,Kadavantra 10% 01 May 2021 01 April 2022 6 Cocoon RJ Group 7/449DF/ Veeky tower,mavelipuram,Kakkanad,cochin-30 5% 11 December 2020 10 December 2021 7 Fab De Moda Convent Road,Erakulam 10% 11 December 2020 10 December 2021 8 Gees fashion boutique Building No:55/1564 C1,Rosjo building,chambakkara,Poonithura,cochin -38 5% 29 December 2020 28 December 2021 9 Globers Update Your Fashion Door No:34/1392,opposite Oberon Mall,By Pass,Edapally 6% 17 December 2020 16 December 2021 10 Jean Shack Jos Junction, D.H Road, M.G Road, Ernakulam 10% 09 December 2020 08 December 2021 11 K.N.R. Sons Club Junction, D.H Road, Ernakulam 10% 09 December 2020 08 December 2021 12 Kahkashan's lucknow chikan palace Ambady building ,Opposite shenoys Theatre,Pillar No:682,MG road 5% 08 December 2020 07 December 2021 13 Kalpana Dresses DH Road,MG road,Ernakulam ,Cochin-16 5% 11 December 2020 10 December 2021 14 Kalpana Dresses Woodland Building,DH road,cochin-16 10% 17 December 2020 16 December 2021 15 L3 Design Studio Covent Road,Shenoys Jn,M.G Road 10% 24 -

Ridership Updation Kochi Metr

Ridership Updation on Kochi Metro and Impact on Pollutants Final Report DISCLAIMER “The present study cannot be construed and be substituted as an investment grade study to secure project financing. Professional practices and available procedures were used in the development of the study findings. However, there is considerable uncertainty inherent in future traffic prediction and reduction in carbon emission forecasts for any Mass transport facility due its dependence on future planning assumptions and master plan predictions. These differences could be material. It should be recognized that traffic and revenue forecasts in this document are intended to reflect the overall estimated long-term trend and not for year on year comparison as for any given year, it may vary due to economic conditions and other factors. The report and its contents are confidential and intended solely for use for the study project. Any use by third parties for use or for publication without the express written consent of CDM Smith is prohibited. CDM Smith i Kochi Metro Rail Ltd. Ridership Updation on Kochi Metro and Impact on Pollutants Final Report LIST OF ACRONYMS LNG: Liquefied Natural Gas GDP: Gross Domestic Product KMRL: Kochi Metro Rail Limited GCDA: Greater Cochin Development Authority IT: Information technology VOC: Vehicle Operation Cost VOT: Value of Time FACT: Fertilisers and Chemicals Travancore Limited TELK: Transformers and Electricals Kerala Limited NH: National Highway KSRTC: Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation JNNURM: Jawaharlal Nehru -

DLF New Town Heights

https://www.propertywala.com/dlf-new-town-heights-kochi DLF New Town Heights - Kakkanad, Kochi 2 & 3 BHK apartments available at DLF New Town Heights DLF New Town Heights presented by DLF Builders with 2 & 3 BHK apartments available at Kakkanad, Kochi Project ID : J300489119 Builder: DLF Builders Location: DLF New Town Heights, Kakkanad, Kochi - 682030 (Kerala) Completion Date: Feb, 2016 Status: Started Description New Town Heights is a new launch by DLF Builders. The project is located at Kakkanad. This is a residential estate which has a enchanting scenic beauty of a mountain valley, with its gently sloping hills and lush green surroundings. Yet, it has excellent access to the rest of Kochi, being on the Seaport-Airport Road. Project Details Total Area of Project: 25.78 Acres Total Blocks: 15 (PHASE - 1) No. of units in Project: 1250+ Common Area/Club House Area: 45000 sqft Percentage of Open Space: 75 Amenities Garden Recreation Facilities 24Hr Backup Maintenance Staff Security Club House Library Community Hall Swimming Pool Health Facilities Tennis Court Badminton Court Gymnasium Indoor Games Basket Ball Court DLF Group is having the existences from six decades now and is built on strong lineage and reputation. It has been a constant competition for the existing and new entrants in the sphere of real estate development. DLF Builders have become a household name that symbolizes unmatched excellence and quality. DLF Developers has a mission which involves growing along with the economical development of the country. The group has a world class foundation based on highest standards of professionalism, ethics and customer service. -

Parking Space in Kochi Issues and Solutions-Zeenab

Working Paper Series Parking Space in Kochi: Issues and Solutions Zeenab Aneez November 2010 Centre for Public Policy Research ©Copyrights Reserved For more information, please contact Centre for Public Policy Research, Door No 28/3656, Sonoro Church Road, Elamkulam, Kochi, Kerala, 682 020 India. Telephone: +91 484 6469177, Fax +91 0484 2323895, E-mail: [email protected] . Or visit the CPPR website at http://www.cppr.in/ Abstract All of India’s cities face an urban transport crisis. While issues such as poor connectivity, bad road quality, traffic congestion, air and noise pollution are constantly talked about, parking is seen as one having negligible effect on the quality of urban transport. The MV Asia study on parking in Mumbai shows that a car spends only 4 per cent of its life in motion and the remaining 96 per cent of the time it is parked (Mumbai Transformation Support Unit 2008) . With the increasing trend in the growth of private vehicles, it is imperative that parking be seen as an important factor for making an efficient transportation system within our cities. In India, parking falls into two categories – Off-street parking and On-street parking. Off-street parking facilities have become popular and are being used by private parties such as shopping malls, theatres and office complexes that recognize parking as a variable that has considerable effect on their success as an enterprise. Customers and/or employees view parking space as a value add to the organisation’s product or service, as they are ensured safe and convenient vehicle parking. The company receives competitive advantage in return. -

Assessment of Noise Pollution at Eranakulam by Gis Ashly

International Journal of Advanced Information Science and Technology (IJAIST) ISSN: 2319:2682 Vol.5, No.10, October 2016 DOI:10.15693/ijaist/2016.v5i10.26-35 ASSESSMENT OF NOISE POLLUTION AT ERANAKULAM BY GIS ASHLY. S1 ANILKUMAR B2 M.Tech. Scholar, Environmental Engineering1 Head of the Department2 Department of Civil Engineering, Malabar College of Engineering & Technology, Desamangalam, Thrissur ABSTRACT In developing country like India with the vehicle population increasing at a rapid rate, the residents of cities are experiencing severe environmental problems that results from road traffic in particular from automobiles. Noise from road traffic is major source of noise pollution and it has detrimental effects on human beings. Fast growing vehicle population in town in the recent years, has resulted in considerable increase in traffic on roads causing alarming noise pollution. In Kerala roads are in bad condition, and poorly maintained and has considerable number of vehicles of outdated technology, the road traffic noise assumes much more importance. Road traffic noise is the most important major source of community noise especially near an important road with high volume of traffic of any major city. Noise affects human body in a number of ways ranging from Psychological to Physiological, e.g. auditory damage, speech interference, sleep interference, general annoyance, reduces the working efficiency, increases blood pressure & fatigue etc. The main objective of this study is to aware the public about the noisy environment with which we lives today, due to the increased urbanization and increased traffic intensity. Using ArcGIS 9.3 software, noise maps are generated to make the awareness more precisely. -

Kakkanad, Kochi

https://www.propertywala.com/rm-bellwoods-kochi RM Bellwoods - Kakkanad, Kochi House Plot at Kakkanad RM Bellwoods is an ongoing house plot project of RM Co's, offering various sizes of Villas plot for sale in Kakkanad, Ernakulam, MG Road, Kochi, Kerala Project ID : J468171190 Builder: RMCo Properties Pvt Ltd. Properties: Residential Plots / Lands Location: RM Bellwoods, Kakkanad, Kochi (Kerala) Completion Date: May, 2013 Status: Started Description RM Bellwoods is an ongoing Villa project of RM Co’s where you will and you can experience a unique life with all amenities and facilities at Bellwoods like Swimming Pool, Party area, Fitness Centre, Landscaped individual courtyard, Landscaped Garden, Drivers/Servants waiting room with Toilets, Tarred internal Roads, Street Lights with backup generator, common OH water tank with water purification unit, Guest Car Parking, & 24 Hours Security. The project is divided into four types – Type A, Type B, Type C & Type D and its sizes are 1877 Sq Ft, 2030 Sq Ft, 2050 Sq Ft, & 2052 Sq Ft respectively. Bellwoods Villas project is located at Kakkanad, Kochi, Kerala. Amenities Swimming Pool Fitness Centre Party Area Landscaped individual courtyard Landscaped Garden Drivers/Servants waiting room with Toilets Tarred Internal Roads Street Lights with back-up generator Compound wall with barbed wire fencing Common OH water tank with water purification unit Guest Car Parking 24 hrs Security RM Co Properties Pvt. Ltd. is a pioneer in real estate development with several years of expertise to its credit. An ISO 9001:2008 certified company, RM Co. Properties introduced the concept of community living in Thrissur, offering fully developed house plots within a gated community. -

Kochi Annual Report 2012-13.Pdf

Young Indians Kochi Chapter Annual Report Annual Report Kochi Chapter 2012-13 Annual Report Kochi Chapter 2012-13 considered employment ready. If India can make capacity building and skill upgradation a priority and take effective steps to plug the gaps, it can indeed become the Message from resource pool of the world. Contents Chairman, CII Kerala State Council To seize the opportunity, the key stake holders – Industry, Academia, Media and Government – need to get together. It is my view that the industry would need to take the lead in creating competencies for the new order. This The greatest strength of any nation is its young people. is where youth organisations like CII’s Young Indians are The youth has the power to influence and shape the required to take leadership roles. The power of youth is future of a country. So if the future has to be bright, the best left to the youth themselves to harness. Message from CII Chairman 03 energy, enthusiasm and idealism of youth need to be My association with Yi has been pretty limited, but I am channelized to the task of nation-building. Message from Yi Chapter Chair 04 given to understand that the CatalYist and ShYishya Message from Yi Chapter Co Chair 05 Youth power is even more significant in India. In 2020, the projects, aimed at sparking the spirit of average age of an Indian citizen will be 29 years entrepreneurshipamongst the youth of Kerala, have been Education 06 compared to 37 years in China and the US, 45 years in a success.