2019 11 06 BC Hydro Final Argument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

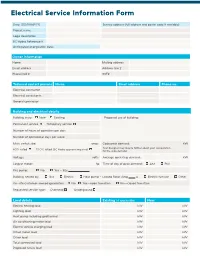

Electrical Service Information Form

Electrical Service Information Form Date: (DD/MM/YY) Service address (full address and postal code if available) Project name Legal description BC Hydro Reference # Anticipated energization date: Owner information Name Mailing address Email address Address line 2 Phone/Cell # GST# Technical contact persons Name Email address Phone no. Electrical contractor Electrical consultants General contractor Building and electrical details Building state: New Existing Proposed use of building: Permanent service Temporary service Number of hours of operation per day: Number of operational days per week: Main switch size: amps Code peak demand: kW Your Designer may inquire further about your computation 80% rated 100% rated (BC Hydro approval required) for the code demand Voltage: volts Average operating demand: kW Largest motor: hp Time of day of peak demand: AM PM Fire pump: No Yes - Size Building heated by: Gas Electric Heat pump - Locked Rotor Amp A Electric furnace Other On-site customer-owned generation: No Yes—open transition Yes—closed transition Requested service type: Overhead Underground Load details Existing (if applicable) New Electric heating load kW kW Lighting load kW kW Heat pump including geothermal kW kW Air conditioning motor load kW kW Electric vehicle charging load kW kW Other motor load kW kW Other load kW kW Total connected load kW kW Proposed future load kW kW Metering Information Total number of meters Residential: Commercial: Voltage: Meter type: 120/240 120/208 347/600 TBD 1 Phase 3 Phase TBD Meter details Other: Temporary master metering required Number of wires: Yes No Current transformer Bar CT lugs conductor size: x Window TBD CT type: Conductor to CT lugs: Cu Al Energization ○ Energization of the project will be scheduled upon receipt of: • Necessary approvals, permits from appropriate authorities, including municipal, electric inspection and other utilities. -

BC Hydro's Response to Intervener Information Requests Round 4

Fred James Chief Regulatory Officer Phone: 604-623-4046 Fax: 604-623-4407 [email protected] November 14, 2019 Mr. Patrick Wruck Commission Secretary and Manager Regulatory Support British Columbia Utilities Commission Suite 410, 900 Howe Street Vancouver, BC V6Z 2N3 Dear Mr. Wruck: RE: Project No. 1598990 British Columbia Utilities Commission (BCUC or Commission) British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority (BC Hydro) Fiscal 2020 to Fiscal 2021 Revenue Requirements Application (the Application) BC Hydro writes in compliance with Commission Order No. G-279-19 to provide its responses to Round 4 information requests as follows: Exhibit B-22 Responses to Commission IRs (Public Version) Exhibit B-22-1 Responses to Commission IRs (Confidential Version) Exhibit B-23 Responses to Intervener IRs (Public Version) Exhibit B-23-1 Responses to Intervener IRs (Confidential Version) BC Hydro is filing a number of IR responses and/or attachments to responses confidentially with the Commission. In each instance, an explanation for the request for confidential treatment is provided in the public version of the IR response. BC Hydro seeks this confidential treatment pursuant to section 42 of the Administrative Tribunals Act and Part 4 of the Commission’s Rules of Practice and Procedure. Overall, BC Hydro received 327 Round 4 information requests. Responses to 260 of those information requests are included in this filing. Thirty-four information requests are the subject of BC Hydro’s letter of November 8, 2019 (the information requests at issue are listed in the attachment to that letter). They are being addressed through the comment process established by Order No. -

BC Hydro and Power Authority 2021/22

BC Hydro and Power Authority 2021/22 – 2023/24 Service Plan April 2021 For more information on BC Hydro contact: 333 Dunsmuir Street Vancouver, BC V6B 5R3 Lower Mainland 604 BCHYDRO (604 224 9376) Outside Lower Mainland 1 800 BCHYDRO (1 800 224 9376)] Or visit our website at bchydro.com Published by BC Hydro BC Hydro and Power Authority Board Chair’s Accountability Statement The 2021/22 – 2023/24 BC Hydro Service Plan was prepared under the Board’s direction in accordance with the Budget Transparency and Accountability Act. The plan is consistent with government’s strategic priorities and fiscal plan. The Board is accountable for the contents of the plan, including what has been included in the plan and how it has been reported. The Board is responsible for the validity and reliability of the information included in the plan. All significant assumptions, policy decisions, events and identified risks, as of February 28, 2021 have been considered in preparing the plan. The performance measures presented are consistent with the Budget Transparency and Accountability Act, BC Hydro’s mandate and goals, and focus on aspects critical to the organization’s performance. The targets in this plan have been determined based on an assessment of BC Hydro’s operating environment, forecast conditions, risk assessment and past performance. Doug Allen Board Chair 2021/22 – 2023/24 Service Plan Page | 3 BC Hydro and Power Authority Table of Contents Board Chair’s Accountability Statement ....................................................................................... -

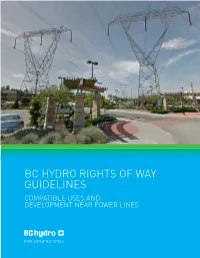

Bc Hydro Rights of Way Guidelines Compatible Uses and Development Near Power Lines Contents

BC HYDRO RIGHTS OF WAY GUIDELINES COMPATIBLE USES AND DEVELOPMENT NEAR POWER LINES CONTENTS OVERVIEW ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................3 WHO ARE THESE GUIDELINES FOR? ................................................................................................................................................................4 PREPARING AND SUBMITTING A PROPOSAL ..................................................................................................................................................5 POSSIBLE COMPATIBLE USES OF RIGHT OF WAY ...........................................................................................................................................6 GENERAL SAFETY INFORMATION .....................................................................................................................................................................7 PLANTING AND LOGGING NEAR POWER LINES ..............................................................................................................................................8 UNDERGROUND INSTALLATIONS .....................................................................................................................................................................9 DESIGNING AROUND BC HYDRO RIGHTS OF WAY .........................................................................................................................................11 -

August 7, 2019 Mr. Patrick Wruck Commission Secretary

Fred James Chief Regulatory Officer Phone: 604-623-4046 Fax: 604-623-4407 [email protected] August 7, 2019 Mr. Patrick Wruck Commission Secretary and Manager Regulatory Support British Columbia Utilities Commission Suite 410, 900 Howe Street Vancouver, BC V6Z 2N3 Dear Mr. Wruck: RE: British Columbia Utilities Commission (BCUC or Commission) British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority (BC Hydro) Fleet Electrification Rate Application BC Hydro writes to file its Application pursuant to sections 58 to 60 of the Utilities Commission Act (UCA) for approval of Rate Schedules 164x – Overnight Rate (150 kW and over) and 165x - Demand Transition Rate (150 kW and over) for use for charging of electric fleet vehicles and vessels. These new services are in response to customer requests for fleet charging rates and support the electrification of commercial fleet vehicles and vessels. For further information, please contact Anthea Jubb at 604-623-3545 or by email at [email protected]. Yours sincerely, (for) Fred James Chief Regulatory Officer ac/tl Enclosure British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority, 333 Dunsmuir Street, Vancouver BC V6B 5R3 www.bchydro.com BC Hydro Fleet Electrification Rate Application August 7, 2019 August 7, 2019 Table of Contents 1 Introduction and Need for Fleet Electrification Rates ......................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of Application .............................................................................. 1 1.2 Need for the Optional Rates ..................................................................... -

Dams and Hydroelectricity in the Columbia

COLUMBIA RIVER BASIN: DAMS AND HYDROELECTRICITY The power of falling water can be converted to hydroelectricity A Powerful River Major mountain ranges and large volumes of river flows into the Pacific—make the Columbia precipitation are the foundation for the Columbia one of the most powerful rivers in North America. River Basin. The large volumes of annual runoff, The entire Columbia River on both sides of combined with changes in elevation—from the the border is one of the most hydroelectrically river’s headwaters at Canal Flats in BC’s Rocky developed river systems in the world, with more Mountain Trench, to Astoria, Oregon, where the than 470 dams on the main stem and tributaries. Two Countries: One River Changing Water Levels Most dams on the Columbia River system were built between Deciding how to release and store water in the Canadian the 1940s and 1980s. They are part of a coordinated water Columbia River system is a complex process. Decision-makers management system guided by the 1964 Columbia River Treaty must balance obligations under the CRT (flood control and (CRT) between Canada and the United States. The CRT: power generation) with regional and provincial concerns such as ecosystems, recreation and cultural values. 1. coordinates flood control 2. optimizes hydroelectricity generation on both sides of the STORING AND RELEASING WATER border. The ability to store water in reservoirs behind dams means water can be released when it’s needed for fisheries, flood control, hydroelectricity, irrigation, recreation and transportation. Managing the River Releasing water to meet these needs influences water levels throughout the year and explains why water levels The Columbia River system includes creeks, glaciers, lakes, change frequently. -

Columbia Basin Plan

FOR REFERENCE ONLY This version is now archived. Updated 2019 Columbia Region Action Plans available at: fwcp.ca/region/columbia-region Photo credit: Larry Halverson COLUMBIA BASIN PLAN June 2012 Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program ........................................................................ 1 Vision ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Principles .................................................................................................................................. 2 Partners .................................................................................................................................... 2 Policy Context ........................................................................................................................... 2 Program Delivery ...................................................................................................................... 4 Project Investment Criteria ...................................................................................................... 4 2. The Columbia River Basin .................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Setting ............................................................................................................................. -

BC Hydro Climate Change Assessment Report 2012

POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON BC HYDRO’S WATER RESOURCES Georg Jost: Ph.D., Senior Hydrologic Modeller, BC Hydro Frank Weber; M.Sc., P. Geo., Lead, Runoff Forecasting, BC Hydro 1 EXecutiVE Summary Global climate change is upon us. Both natural cycles and anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions influence climate in British Columbia and the river flows that supply the vast majority of power that BC Hydro generates. BC Hydro’s climate action strategy addresses both the mitigation of climate change through reducing our greenhouse gas emissions, and adaptation to climate change by understanding the risks and magnitude of potential climatic changes to our business today and in the future. As part of its climate change adaptation strategy, BC Hydro has undertaken internal studies and worked with some of the world’s leading scientists in climatology, glaciology, and hydrology to determine how climate change affects water supply and the seasonal timing of reservoir inflows, and what we can expect in the future. While many questions remain unanswered, some trends are evident, which we will explore in this document. 2 IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON BC HYDRO-MANAGED WATER RESOURCES W HAT we haVE seen so far » Over the last century, all regions of British Columbia »F all and winter inflows have shown an increase in became warmer by an average of about 1.2°C. almost all regions, and there is weaker evidence »A nnual precipitation in British Columbia increased by for a modest decline in late-summer flows for those about 20 per cent over the last century (across Canada basins driven primarily by melt of glacial ice and/or the increases ranged from 5 to 35 per cent). -

2020 08 13 Exhibit B 57 BC Hydro

Fred James Chief Regulatory Officer Phone: 604-623-4046 Fax: 604-623-4407 [email protected] March 13, 2020 Mr. Patrick Wruck Commission Secretary and Manager Regulatory Support British Columbia Utilities Commission Suite 410, 900 Howe Street Vancouver, BC V6Z 2N3 Dear Mr. Wruck: RE: Project No. 1598990 British Columbia Utilities Commission (BCUC or Commission) British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority (BC Hydro) Fiscal 2020 to Fiscal 2021 Revenue Requirements Application BC Hydro writes to provide its responses to the following undertakings resulting from the Oral Hearing of February 24 to March 4, 2020: Exhibit B-57 Responses to Undertaking Nos. 36, 42, 43, 48, 52, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 63, 64, 65 and 66 (Public Version) Exhibit B-57-1 Responses to Undertaking Nos. 43 and 48 (Confidential Version) Further, BC Hydro writes to make the following corrections to testimony provided during the Oral Hearing of February 24 to March 4, 2020. At this time, BC Hydro is not aware of any other corrections that need to be made to the record. Transcript Excerpts of Transcript Correction Reference Volume 12, MR. KEEN: And Mr. Leonard, to what extent BC Hydro has had joint Page 2151, does BC Hydro cooperate or coordinate with the meetings, where Line 6 to customer making the interconnection request in appropriate, with Page 2153, the course of consultation? representatives of Line 8 … BC Hydro, First Nations, and customer proponents MS. HOLLAND: I can't think at the moment of attending. any meetings that we have done jointly. What I am aware of is that there's often ongoing dialogue between the consultation lead for the proponent, who's often undertaking their own consolation, it's helpful for us to have an understanding of what their relationship is and any agreements they have. -

BC Hydro Responses to Round 1 BCUC Staff Information Requests

Fred James Chief Regulatory Officer Phone: 604-623-3918 Fax: 604-623-4407 [email protected] April 1, 2021 Mr. Patrick Wruck Commission Secretary and Manager Regulatory Support British Columbia Utilities Commission Suite 410, 900 Howe Street Vancouver, BC V6Z 2N3 Dear Mr. Wruck: RE: British Columbia Utilities Commission (BCUC or Commission) British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority (BC Hydro) Fiscal 2020 to Fiscal 2021 Revenue Requirements Application Compliance Filing BC Hydro writes to provide its responses to Round 1 BCUC Staff information requests. For further information, please contact Chris Sandve at 604-974-4641 or by email at [email protected]. Yours sincerely, Fred James Chief Regulatory Officer cs/rh Enclosure British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority, 333 Dunsmuir Street, Vancouver BC V6B 5R3 www.bchydro.com British Columbia Utilities Commission Staff Page 1 Information Request No. 1.1.1 Dated: March 1, 2021 of 1 British Columbia Hydro & Power Authority Response issued: April 1, 2021 British Columbia Hydro & Power Authority Fiscal 2020 to Fiscal 2021 Revenue Requirements Application Compliance Filing 1.0 A. SECTION 3 – ENERGY STUDIES MODELS Reference: ENERGY STUDIES MODELS British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority Fiscal 2020 to Fiscal 2021 Revenue Requirements Application Compliance Filing dated December 1, 2020 (Compliance Filing), Section 3.1.3, 3.2.1, pp. 29, 33 Resource Mix On page 29 of the Compliance Filing, British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority (BC Hydro) states: Over a number of years, the generation from BC Hydro’s hydroelectric facilities must be about equal to the inflows that have occurred, subtracting inflow that is spilled. -

COQMON-7 | Lower Coquitlam River Fish Productivity Index

Coquitlam-Buntzen Project Water Use Plan Lower Coquitlam River Fish Productivity Index Implementation Year 12 Reference: COQMON-7 Study Period: 2000-2017 Results Prepared by: Jody Schick Jason Macnair 529 Gower Point Road, 2919 Ontario St., Vancouver B.C. Gibsons, BC., V5T 2Y5 V0N 1V0, [email protected] [email protected] March 31, 2019 Coquitlam River Fish Monitoring Program: 2000-2017 Results Final Report Prepared for: BC Hydro Prepared by: Jody Schick1* and Jason Macnair2 _____________________________________________________________________ 1 529 Gower Point Road, Gibsons, BC., V0N 1V0, [email protected] 2 2919 Ontario St., Vancouver B.C. V5T 2Y5, [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed ii Executive Summary As part of the Coquitlam River Water Use Plan (LB1 WUP), a long-term adaptive management study is being conducted in the Coquitlam River to compare anadromous fish production under two experimental flow regimes. Fish population monitoring under the first flow regime (Treatment 1, dam release flows from 0.8-1.4 cms) occurred from 2000 until the completion of the Coquitlam Dam seismic upgrade in October 2008, with the exception of 2001(8 years). Fish production under Treatment 2 (release flows from 1.1-6.1 cms) will be monitored for up to 9 years. The Lower Coquitlam River Fish Productivity Index Monitoring Program (COQMON-07) focuses on four anadromous species: Steelhead Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) and Pink Salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), and includes adult escapement and smolt outmigration monitoring for each species. Higher returns during 2007-2014 allowed Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) escapements to be estimated as well. -

CABRO Crown Agency Registry

British Columbia Crown Agency Registry Crown Agencies and Board Resourcing Office Ministry of Finance August 2020 1 Crown Agencies by Classification Commercial Crown Corporations • BC Lottery Corporation • Columbia Power Corporation • BC Railway Company • BC Hydro and Power Authority o 0839565 BC Ltd. and 0838465 BC Ltd. o Powerex Corporation o BC Railway Properties Ltd. o Powertech Labs Inc. o Vancouver Wharves Ltd. and Vancouver Wharves Ltd. Partnership • Insurance Corporation of BC Service Delivery Crown Corporations • BC Assessment Authority • BC Securities Commission • Knowledge Network • BC Family Maintenance • BC Transit Corporation Corporation Agency • British Columbia Council for • Knowledge-West • BC Financial Services International Education Communications Authority • British Columbia Trade and Corporation • BC Games Society Invest Ltd. • Legal Services Society of • BC Housing Management • Columbia Basin Trust British Columbia Commission • Creston Valley Wildlife • Nechako-Kitimaat • BC Immigrant Investment Management Authority Development Fund Society Fund Ltd. • Destination British • Organized Crime Agency of • BC Infrastructure Benefits Columbia British Columbia • BC Liquor Distribution • First People’s Cultural • Partnerships BC Branch Council • Provincial Rental Housing • BC Oil and Gas Commission • Forest Enhancement Corporation • BC Pavilion Corporation Society of BC • Real Estate Council of • Industry Training Authority • Forestry Innovation British Columbia • Innovate BC Investment Ltd. • Real Estate Foundation of