Gilad Padva Baal Baalev.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shabbat Parshat Vaera at Anshe Sholom B'nai Lsrael Congregation

Welcome to Shabbat Parshat Vaera ANNOUNCEMENTS at Anshe Sholom B’nai lsrael Congregation We regret to inform you of the passing of Charles Smoler, father of Adam Smoler. January 12 – 13, 2018 / 26 Tevet 5778 Shiva will take place at Adam & Libby's home (507 W. Roscoe St. #2) Sunday, January 14, 10:00 AM - 1:00 PM & 5:15 - 8:30 PM, and Monday, January 15, 5:15 - 8:00 PM. May the memory of the righteous be a blessing and a comfort to us Kiddush is co-sponsored by Milt’s BBQ. all. Amen. ASBI Board of Directors: The next ASBI Board of Directors meeting is Monday, January 15, at 7:00 PM. Thank you to this week’s volunteer Tot Shabbat leader, Mayer Grashin, and SCHEDULE FOR SHABBAT volunteer readers, Yinnon Finer & Josh Shanes. Friday, January 12 Light Candles 4:23 PM Mincha, Festive Kabbalat Shabbat & Ma’ariv 4:25 PM ANSHE SHOLOM TRIBUTES Saturday, January 13 Aliyah Hashkama Minyan 8:00 AM Neil Berkowitz Shacharit with sermon by Rabbi Wolkenfeld 9:00 AM Alan Hepker A User's Guide to Prophecy Youth Tefillah Groups (see inside for details) 10:30 AM In Memory of Charles “Chip” Smoler, a”h Daf Yomi & Parsha Discussion with Dr. Leonard Kranzler 12:30 PM Donald & Julia Aaronson Mincha followed by Shalosh Seudot 4:10 PM R. Yehuda Aaronson Havdalah 5:24 PM Alison & Eytan Fox Denise & Stuart Sprague Yahrzeit Repeat Evening Sh’ma: January 12, after 5:26 PM Ruth Binter in memory of her father, Gershon Zev Futerko, a”h, and her mother, Latest time to recite Morning Sh’ma: January 13, 9:38 AM Chaya Futerko, a”h Allen Hoffman in memory of Dr. -

Hartford Jewish Film Festival Film Festival

Mandell JCC | VIRTUAL Mandell JCC HARTFORD JEWISH HARTFORD JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL Mandell JCC | VIRTUAL Mandell JCC HARTFORD JEWISH HARTFORD JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL FEBRUARY 28-APRIL 2, 2021 | WWW.HJFF.ORG Zachs Campus | 335 Bloomfield Ave. | West Hartford, CT 06117 | www.mandelljcc.org FILM SCHEDULE All films are available to view starting at 7:00pm. Viewing of films on the last day can begin up until 7:00pm. All Film Tickets - $12 per household DATE FILM PAGE TICKETS Feb 28-March 3 Holy Silence 11 Buy Now March 2-5 Asia 13 Buy Now March 3-6 Golden Voices 15 Buy Now March 5-8 Advocate 17 Buy Now March 6-9 When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit 19 Buy Now March 8-11 Here We Are 21 Buy Now March 9-12 ‘Til Kingdom Come 23 Buy Now March 11-14 Sublet 25 Buy Now March 13-16 My Name is Sara 27 Buy Now March 15-18 City of Joel 29 Buy Now March 16-19 Shared Legacies 30 Buy Now March 18-21 Incitement 33 Buy Now March 20-23 Thou Shalt Not Hate 35 Buy Now March 21-24 Viral 37 Buy Now March 23-26 Those Who Remained 39 Buy Now March 25-28 Latter Day Jew 41 Buy Now March 25-26 & 28-30 Mossad 43 Buy Now March 29-April 1 Shiva Baby 45 Buy Now March 30-April 2 The Crossing 47 Buy Now Mandell JCC Ticket Assistance: 860-231-6315 | [email protected] 2 | www.hjff.org SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 28 1 2 3 4 5 6 HOLY SILENCE GOLDEN VOICES ASIA WHEN.. -

Resume Wizard

Israeli Cinema Course ID ICINE-UT 0136 (Cinema Studies, Tisch)/DRLIT-UA 9524 (Dramatic Literature) Eytan Fox Instructor Details with Hannah Brown [email protected] [email protected] Hannah 02-570-2077; 054-438-5100 Eytan 052-822-2202 Class Details Fall Semester 2011 Wednesdays 17:15-20:15 Prerequisites No prerequisites Class Eytan Fox, one of Israel’s most acclaimed directors, will teach a course on the art of filmmaking. He Description will use his work to discuss the history and culture of Israel. For their final assignment, the students will write a proposal for a film based on their experiences in Tel Aviv. Putting Fox’s work in the context of Israeli cinema, Jerusalem Post film critic and novelist Hannah Brown will give a three-part survey of Israeli film history and will suggest a viewing list for students, as well as giving a brief introduction to critical theory and writing. Students will write a critical essay on a film they have seen in the course in which they will analyze the work and put it in the context of Israeli cinema. In addition, other established Israeli directors, including Ari Folman and Hagai Levy will guest lecture. Course To give students an understanding of and appreciation for the creative process of filmmaking, through Objectives an examination of the work of director Eytan Fox by the director himself, and to give a history of Israeli cinema in order to place his work in this context. Grading and 1. Midterm critical essay – 40% Assessment 2. Final film proposal – 60% Required Brown, Hannah. -

Brand Israel "Pinkwashing" in Historical Context

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 8-2013 Recycled rhetoric: brand Israel "pinkwashing" in historical context Joy Ellison DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ellison, Joy, "Recycled rhetoric: brand Israel "pinkwashing" in historical context" (2013). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 149. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/149 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECYCLED RHETORIC: BRAND ISRAEL “PINKWASHING” IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts June 2013 BY Joy Ellison Department of Women’s and Gender Studies College of Liberal Arts and Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter One Introduction: “Pinkwashing” Israeli Settler-Colonialism ............................................................................. 3 Chapter Two Proven Strategies: Analyzing Brand -

FOR MY FATHER (Sof Shavua B'tel Aviv) Directed by Dror Zahavi

FOR MY FATHER (Sof Shavua B'Tel Aviv) Directed by Dror Zahavi “Quite simply the most powerful and moving film I can remember seeing in years. A near perfect film!” - The Huffington Post Israel & Germany / 2008 / Drama In Hebrew with English subtitles / 100 min. Film Movement Press Contact: Claire Weingarten │ 109 W. 27th Street, Suite 9B │ New York, NY 10001 │ tel: (212) 941-7744 x 208 │ fax: (212) 491-7812 │ [email protected] Film Movement Theatrical Contact: Rebeca Conget │ 109 W. 27th Street, Suite 9B │ New York, NY 10001 │ tel: (212) 941-7744 x 213 │ [email protected] SYNOPSIS Tarek, a Palestinian forced on a suicide mission in Tel Aviv to redeem his father’s honor, is given a second chance when the fuse on his explosive vest fails to detonate. Forced to spend the weekend in Tel Aviv awaiting its repair, Tarek must live amongst the people he was planning to kill. To his surprise he connects with several Israelis on the outskirts of society, including the beautiful Keren, who has cut off contact with her Orthodox family and upbringing. With nothing to lose, Tarek and Keren open up to one another, and an unlikely love blooms between two isolated and damaged individuals raised to be enemies. However, with the deadly load of explosives still strapped to him, he must spend 48 hours in the city, caught between the men that sent him—who can blow up his bomb remotely--, the Israeli police patrolling the streets and his new-found companions. Spending this time with Keren and his new friends, Tarek discovers the spark of life returning to fill his soul, and when the weekend ends, Tarek must make the decision of his life. -

ANNUAL IMPACT REPORT the Festival Growth Analysis 10 Israeli Cinema 35 Social Media Building Bridges Year-Round Vs

Transforming the way people see the world through film 3 Contents Who We Are Artistic Excellence 4 Welcome Letter 33 Recognized as one of the MJFF in 2021 “50 Best Film Festivals in the Audience Experience World” by MovieMaker Magazine ANNUAL IMPACT REPORT The Festival Growth Analysis 10 Israeli Cinema 35 Social Media Building Bridges Year-Round vs. Next Wave Festival Audience Ibero-American Cinema Made in Florida Film Market & Distribution Sustainability In Conversation Live Festival Experience 37 Sponsorship Media Coverage Membership Year-Round 24 Community Initiatives Year-Round Program Virtual Screening Room Speaker Series Screening the Holocaust Despite tremendous challenges, the We also intensified our overall diversity immense success the Miami Jewish Film and inclusion efforts and our support for Festival (MJFF) has achieved this year is women both in front of and behind the astounding. In the following pages, we camera. MJFF’s inclusion initiative share our successes from last year, which included its “Next Wave” program targeted Building confirm what we’ve always believed: that to 21-35-year-old college students and film helps us better understand one young professionals, the “Focus on LGBT another, encourages empathy, and fuels a cinema” program, and the “Building more engaged and connected world. These Bridges/Breaking Barriers” program that is Connections timeless values drew record audiences to dedicated to presenting stories that align the Miami Jewish Film Festival in 2020 and, the power that exists in the connection we believe, will endure when the time between the Black and Jewish comes to welcome guests back to our communities in a time of rising racism and & Embracing cinemas. -

Israeli Film Syllabus

Zerubavel, Israeli Society Though Film Course info Professor Zerubavel’s info Jewish Studies 01:563:393:01 Email: [email protected] Cinema Studies 01:175:377 Tel (messages): 732-932-2033 Comparative Literature: Office hours: TBA, Bildner Center, 1st fl Mondays 2:50pm-5:50pm Bildner Center, 12 College Ave, room 107 Whereas early Israeli films focused on the nation-building effort, Israeli cinema has become increasingly diverse, critical, and multicultural in its orientation. Given this dramatic development, films provide a fascinating window to explore some key developments in Israeli life while exploring the development of Israeli cinema and the significance of film as a distinct art form. The films and the readings introduce questions that are a key to understanding major social, political, and cultural issues which the course explores: How did a society of immigrant Jews from numerous countries evolve into an “Israeli” society before the foundations of the state in 1948? What was the experience of growing up in Israel of the 1950s? What was the impact of the Holocaust on the young Israeli society and how has it changed overtime? What was the unique communal life and children-rearing method of the kibbutz and how has the kibbutz been transformed in recent decades? What is the impact of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict on Israeli life and on Jewish-Arab relations within and outside of Israel? How is the diversity of Jewish religious life depicted in film? How are Israeli gender and queer identities constructed and portrayed in various settings? Students will view films and write responses to them and prepare the readings assignments as part of their own going work in advance of each class. -

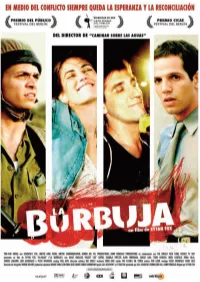

Eytan Fox En 2002

SINOPSIS Tres jóvenes israelíes, dos chicos y una chica, comparten un apartamento en el barrio más exclusivo de Tel Aviv. Intentando dejar a un lado los conflictos políticos y centrarse en sus vidas y sus amores, estos veinteañeros modernos son a menudo acusados de vivir en una burbuja escapista. Mientras se encuentra en la reserva del ejército en Cisjordania, Noam, dependiente de una tienda de música, se cruza en su camino con Ashraf, un chico palestino. Cuando se encuentran en Tel Aviv, ningún tabú cultural puede frenar la atracción sexual entre ellos. Por otra parte, la testaruda Lulu, que trabaja en una tienda de productos para el baño, se enfurece cuando es rechazada por un atractivo joven tras acostarse con ella en la primera cita. Poco sospecha que el hombre de su vida puede estar justo ahí. Por último, Yali, encargado de un café-restaurante de moda, intenta abarcar más de lo que puede manejar cuando empieza a salir con un agresivo chico, cuyos modales de provincia no alcanzan sus estándares. Como Noam y Ashraf se enamoran, sus amigos israelíes deciden ayudar al palestino a quedarse de manera ilegal en Tel Aviv. Acuerdan que Ashraf se ponga ropas menos sospechosas, que adopte un nombre hebreo y que trabaje en el café de Yali. Habiendo sido educado de manera tradicional, el joven palestino es conquistado por la permisiva vida de la ciudad y desea con compartir con su hermana su nuevo amor. Soñando con el día en que su amada Tel Aviv esté libre de problemas políticos, el grupo de amigos organiza una fiesta en la playa contra la ocupación, pero los buenos tiempos compartidos y la diversión pronto irán más allá de las decepciones y los enredos amorosos. -

The Repressed Israeli Trauma of Immigration

arts Article Three Mothers (2006) by Dina Zvi-Riklis: The Repressed Israeli Trauma of Immigration Yael Munk Department of Literature, Language and the Arts, The Open University of Israel, Ra’anana 4353701, Israel; [email protected] Received: 26 February 2020; Accepted: 8 June 2020; Published: 16 June 2020 Abstract: This article relates to the complex approach of Dina Zvi-Riklis’ film Three Mothers (2006) to immigration, an issue that is central to both the Jewish religion and Israeli identity. While for both, reaching the land of Israel means arriving in the promised land, they are quite dissimilar, in that one is a religious command, while the other is an ideological imperative. Both instruct the individual to opt for the obliteration of his past. However, this system does not apply to the protagonists of Three Mothers, a film which follows the extraordinary trajectory of triplet sisters, born to a rich Jewish family in Alexandria, who are forced to leave Egypt after King Farouk’s abdication and immigrate to Israel. This article will demonstrate that Three Mothers represents an outstanding achievement, because it dares to deal with its protagonists’ longing for the world left behind and the complexity of integrating the past into the present. Following Nicholas Bourriaud’s radicant theory, designating an organism that grows roots and adds new ones as it advances, this article will argue that, although the protagonists of Three Mothers never avow their longing for Egypt, the film’s narrative succeeds in revealing a subversive démarche, through which the sisters succeed in integrating Egypt into their present. -

The Bubble Janeen 403110072 Jessica 403110632 Paul 403110498 Sofia40311046 Zoe Liao403110436

Alice 403110527 Charviel 403110 The Bubble Janeen 403110072 Jessica 403110632 Paul 403110498 Sofia40311046 Zoe Liao403110436 https://pittqueercinema.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/the-bubble1.jpg Outline (+Work Division) I. Introduction A. Background information 1: the Director and the Film’s Historical Background-Zoe B. Conflicts between Israel and Palestine -Janeen C. Background information 2: Trivia-Zoe C. Thesis statement-Jessica D. The meaning of the word “bubble” -Jessica II. key Elements presenting “bubble” A. Language & Music as Bubble-Sofia B. Love relationships & gender issues-Charviel C. Living conditions-Paul III. Conclusion-Alice A. Restate thesis statement B. Interesting questions Background Information: the Director and the Film’s Historical Background (Zoe) Background information Director: Eytan Fox •Born in NYC, moved to Jerusalem, Israel •Served in the army •Openly gay •Common themes in his films: 1.LGBTQ 2.Love between military men 3.Israeli–Palestinian conflict Background information •Screenwriters: Eytan Fox & Gal Uchovsky Gal Uchovsky •Writer and journalist •Fox’s partner •Collaborate with Fox http://www.elisarolle.com/romance/images/EytanFoxAndGalUchovsky2.jpg LGBT in Tel Aviv, Israel Voted the best gay city in the world by American Airlines in 2012 “Tel Aviv is a true gay oasis in the Middle East. A city that is secular, liberal and friendly. The atmosphere is open and welcoming and people are as warm as the weather.” (Peretz) Israel is the first and only country in Asia to recognize unregistered cohabitation between same sex couples so far. Israeli–Palestinian conflict •1900 •Idea of statehood •Many Jewish people who spread around the world came back to the land. -

Walk on Water Nyr

(/) WALK ON WATER NYR By Erica Abeel (Http://Www.Filmjournal.Com/Taxonomy/Term/93) Feb 7, 2005 Like Share Tweet Reviews (//www.pinterest.com/pin/create/button This fourth feature from Eytan Fox, the Tel Aviv-based director of Yossi & Jagger, points up what's missing from the claustrophobic, navel-gazing films that often reign at Sundance, and typify the American indie repertoire. Made for a modest 1.4 million dollars, Walk on Water tackles big issues in the larger world. Fox weaves a multi-layered drama out of themes ranging from sexual identity and Israeli-style machismo, to co-existence with the Arabs, to forging ties with Berliners descended from Nazis. And he achieves this, for the most part, not with a didactic message, but through quietly engaging characters. In an attention-hooking opening, tough Mossad operative Eyal (sexy Lior Ashkenazi of Late Marriage) offs a terrorist he's been tailing with steely competence. He's next assigned to track down one of the last surviving Nazi war criminals. When Eyal objects that the man is already old and ill and no one cares anymore, his boss replies, in one of the film's many pungent lines, "I want to get him before God does." In order to discover the war criminal's whereabouts, Eyal reluctantly agrees to pose as a tour guide for his grandson Axel (Knut Berger), who has come to Israel from Berlin to visit his kibbutznik sister Pia (Carolina Peters). By bugging Pia's apartment, Eyal achieves his mission. But he hasn't counted on connecting big-time with both sister and brother (who, it turns out, is gay), which transforms him in amusing and heart-tugging ways. -

NYU Tel Aviv ICINE-UT 136; DRLIT-UA 9524 Israeli Cinema

NYU Tel Aviv ICINE-UT 136; DRLIT-UA 9524 Israeli Cinema Instructor Information ● Eytan Fox ● Mobile: +972-52-8222202 ● Email: [email protected] ● Office Hours: by appointment Course Information ● ICINE-UT 136; DRLIT-UA 9524 ● Israeli Cinema ● Eytan Fox, one of Israel’s most acclaimed directors, will teach a course on the art of filmmaking. He will use his work to discuss the history and culture of Israel. The course will enrich the students’ understanding of Israeli Cinema as a microcosm of the young, vibrant, and continually changing Israeli state and society. Students will analyse the cinematic expression of the themes behind the inception and evolution of the small yet multifaceted country, and note the differences between the cinema of the first and second wave of Israeli filmmakers. In addition, other Israeli actors and directors will be invited to give guest lectures ● Prerequisites: None ● Tuesdays, 1:30pm-4:30pm ● NYUTA Academic Center, 17 Brandeis Street, Innovation Studio Course Overview and Goals Upon Completion of this Course, students will be able to: ● Understand the framework of and appreciation for the creative process of filmmaking, through an examination of the work of director Eytan Fox. ● Think and write like a film critic. ● Understand the history, culture and politics of Israel through the prism of art and cinema. Course Requirements Class Participation Page 1 Students are expected to attend class regularly and arrive on time. Students must complete all assigned readings before the class meeting and be prepared to participate actively in discussions of the readings and current events. Film Presentation Each student will select an Israeli film to watch on their own, present clips from the films to the class, and write an essay summarizing and critiquing the main artistic and cultural themes of the film.