Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethics and Good Living

PHI 171 Ethics and Good Living Image by Rockinpaddy, “Philosophy Conference,” Creative Commons 2.0, downloaded from https://www.flickr.com/photos/rockinpaddy/217124668/in/photosstream/, last accessed July 10, 2020. Written, edited, and compiled by Dr. Samuel Bruton These materials are the product of Dr. Bruton’s successful application to participate in the University of Southern Mississippi’s Open Textbook Initiative, supported by the Office of the Provost and the University Libraries. Dr. Bruton gratefully recognizes the help of Josh Cromwell throughout the process. PHI 171 – Ethics and Good Living – Table of Contents 0. Setting the Stage 0.1 How to Take Notes p. i 1. Socrates p. 1 1.1 Socrates – Background and Themes 1.2 Apology 1.3 Apology Study Guide 1.4 Crito 1.5 Crito Study Guide 2. Stoicism p. 28 2.1 Stoicism – Background and Themes 2.1 Epictetus - Enchirichiodon I 2.2 Epictetus - Enchirichiodon II 2.3 Epictetus - Enchirichiodon III 2.4 Epictetus – Study Guide 3. Buddhism p. 48 3.1 Buddhism – Background and Themes 3.2 Buddhism – Core Values 3.3 Buddhism – The Eight Fold Path 3.4 Buddhism – Ethics 4. Christianity p. 82 4.1 Sermon on the Mount 4.2 Pascal – Background and Themes 4.3 Pensées I. 4.4 Pensées II. 4.5 Pascal – Study Guide 5. Frankl p. 111 5.1 Viktor Frankl – Background and Themes 5.2 Man’s Search for Meaning, summary and quotations 5.3 Frankl Study Questions 6. Nietzsche p. 116 6.1 Schopenhauer – Background and Themes 6.2 Schopenhauer – On the Suffering 6.3 Nietzsche – Background and Themes 6.4 Nietzschean Aphorisms 6.5 Nietzsche – Selections from Daybreak (Dawn of the Day) 6.6 Nietzsche – Study Guide 7. -

California State University, Northridge Billy's Pardon A

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE BILLY’S PARDON A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Screenwriting by Aaron Dean Sherrill May 2013 The thesis of Aaron Dean Sherrill is approved: Sturgeon, Scott A, M.F.A. Date Portnoy, Kenneth S, Ph.D. Date Edson, Eric, M.F.A., Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to: My family and friends who have supported my creativity and without them, I would not be where I am right now. Thank you! iii ACKNOWLEDGMENT I would like to thank my committee members who supported my efforts in writing this thesis. To my chair, Professor Eric Edson, Who literally gave me a playbook of notes to help me navigate the rough and wild waters of my thesis and helped me to keep on task till the end. To Professor Scott Sturgeon, Who stayed in my corner since day one, and gave me positive feedback even when I felt down, and picked up my spirits making me excited to write on and keep going. To Professor Kenneth Portnoy, Whose tough love made think more critically about my work and helped me to become a better writer. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………………… ii Dedication ……………………………………………………………………………….iii Acknowledgement ……………………………………………………………………….iv Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………vi Billy’s Pardon …………………………………………………………………………….1 v ABSTRACT BILLY’S PARDON by Aaron Dean Sherrill Master of Arts in Screenwriting Billy’s Pardon is a western drama about Billy, a young ranch hand who, after killing a local bully in self-defense wants to flee from the backlash and goes on the run to start a new life. -

Reversing the Gaze: Wasu, the Keys and the Black Man on Europe And

Reversing the Gaze:Wasu, The Keys and The Black Man on Europe and Western Civilization in the Interwar Years, 1933-1937 by Brittony Chartier A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2012 Brittony Chartier Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94595-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94595-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Outlines the Grade Scale Percentage Equivalents Used in the Department of Communication, Media and Film

1 University of Calgary Department of Communication, Media and Film Film Studies FILM 305.18 L01 Topic in Film Genres: The Horror Film Fall 2016 September 12 – December 7 (excluding Oct. 10) Lecture: Wednesday 17:00 – 18:50, Lab: Monday 17:00 – 19:45 Instructor: Murray Leeder Office: SS220 Office Phone: 22903381 E-Mail: [email protected] Web page: D2L available through MyUofC portal Office Hours: Wednesdays 16:00-17:00, Thursdays 11:30-12:30 Course Description The horror film is one of cinema's most durable genres, having gone through countless permutations over time. Often horror films are understood as being linked directly to the unconscious anxieties of the societies that spawn them – to understand a culture, we must know what it fears. This class examines the “classical period” of the horror film, from its inception till 1960, when Psycho is generally understood as marking a key turning point in the genre's history. It covers such material as the German and American silent horror traditions, the Universal Horror classics like Dracula and Frankenstein, Val Lewton's famously elegant and moody horror films, 50s paranoid and gimmick films, and Hammer Pictures' bloody and colourful new visions. A major ambition of this class is to show how horror can serve as a gateway into a fascinating set of historical and critical issues of race, gender, science, politics and more. What do these horror films tell us about the cultures that produced them? How do they construct “monstrosity”, and how do we see the road to the horror films of our time displayed in these early films? Objectives of the Course Attendance at lectures, screenings and tutorials, and informed participation are essential components of this course and will help determine your final grade. -

Steps Ahead of the Celebration on Page 4 Scholarships/Legacy 2

Vol. 24 No. 7 THE AMERICAN LEGION NEWS ALERT Paid Up For Life membership American Legion members interested in the discounted March 2014 A National Headquarters Publication Paid Up For Life membership can easily join online. Once 100TH ANNIVERSARY registered, members can either pay in full or pay in 12 monthly installments. Join the other 200,000 Paid Up For Life Legionnaires by visiting: www.legion.org/join/pufl Watch 77th Oratorical Bob Ferrebee of Post 41 in Berryville, Contest live Va., has spent the The American Legion High past eight years School Oratorical Scholarship researching and Program, “A Constitutional compiling the rich Speech Contest,” is April 4-6 in history of his post. Indianapolis at the Wyndham Photo by John Napolitano hotel. Watch the top three finalists compete live April 6 at STEPS AHEAD OF 10 a.m. (EDT): www.legiontv.org THE CELEBRATION Register online for Legacy Run Virginia post adjutant and historian has early start on American Legion’s centennial. Online registration is underway for this year’s American Legion By Laura Edwards Legacy Run. The run departs Bob Ferrebee grew up in Berryville, Va., General Corp., and since 1989 Post 41 has met Indianapolis Aug. 17 and then served in the Army during the Vietnam in the basement of the building it constructed, arrives in Charlotte Aug. 21. War and taught high school math. Now renting out the top part to the discount store. Last year, nearly 400 Legion retired, one of his hobbies is history, from the Roughly $40,000 in yearly income pays for all Riders raised $334,000 during personal – Ferrebee has family photos going the post’s programs. -

Filmclips for Character Education

FILM clips for Character Education Hon est y FEATURING Short, fully-licensed film clips from these popular movies: Liar Liar To Kill A Mockingbird Abbott & Costello Big Fat Liar FILM clips for Character Education Page 2 Hon est y Theme: Trustworthiness A young son makes a birthday wish that his father, a chronic liar, must tell the truth for twenty- four hours. Thanks to a bit of magic, his wish comes true. It does not take long before this liar-turned-truth-teller begs his son to take back the wish! Clip 1 of 4 (2:16) Grown Ups Lie Liar Liar (PG-13) Teaser Question: ARE “WHITE LIES” OKAY? WHY? WHY NOT? AN ICEBREAKER See where students stand relative to each other and how strongly they feel about their position regarding their answer to the Teaser Question with an activity called “The Power Line,” adapted from the work of Hannah Lein. Designate one side of the room as YES and the other side of the room as NO. Invite students to move to the point in the line where their answer lies. Maybe they’re in the middle, thinking sometimes yes, sometimes not, so they’ll stand in the middle. Encourage them to talk with the people around them as they line up to make sure they’re in the right spot, the place on “The Power Line” that shows where they stand in this discussion. Once they have placed themselves where they belong, ask them to explain why they are where they are on the continuum between YES and NO. -

Script Images & Sound Reference

THE GAME IS ON!: THE UNRELIABLE NARRATOR – ANNOTATED SCRIPT IMAGES & SOUND REFERENCE 5.1 J: Sherlock, can you hear me? 5.2 Sherlock and John by Matchlight From: Night scene (1616-17), by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), and A lady (design) admiring an earring by candlelight, by Godfried Schalcken (1643-1706) We wanted an atmospheric opening, in darkness and shadow, and these seventeenth century paintings provided an appropriate touchstone. 5.3 Scene Rotation From: Stranger Things (2016-) The TV series Stranger Things, which features an alternate dimension called the Upside Down, offers an homage to 1980s pop culture, drawing on the work of Steven Spielberg, Stephen King, as well as many other films, anime and video games. Moreover, the principal mystery at the heart of the first series concerns the whereabouts of a missing boy (Will, played by Noah Schapp). As such, it provided an obvious point of reference for this episode of TGIO. We decided to emulate the technique from the opening credits, involving the screen turning upside down. We also borrow from Stranger Things in our use of lights strung throughout the forest. See 5.20 for further details. Interestingly, in April 2018, filmmaker Charlie Kessler filed a lawsuit against the Duffer Brothers, claiming that their idea for the basic story of Stranger Things was copied from his 2011 short film Montauk. 1 THE GAME IS ON!: THE UNRELIABLE NARRATOR – ANNOTATED 5.4 SFX (sighs) From: Dante’s Inferno, the first part of the epic poem Divine Comedy (1308-21) One of the first sounds we hear in The Unreliable Narrator is a series of sighs. -

Queer Slashers

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations January 2018 Queer Slashers Peter Marra Wayne State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Marra, Peter, "Queer Slashers" (2018). Wayne State University Dissertations. 2049. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/2049 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. QUEER SLASHERS by PETER MARRA DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2018 MAJOR: ENGLISH (Film & Media Studies) Approved By: ____________________________________ Advisor Date ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ DEDICATION For Jon, without whom this would not be possible ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication.........................................................................................................................ii Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Strange Pleasure: 1940s Proto-Slasher Cinema...........................................26 -

University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue 02 | Spring 2006

University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue 02 | Spring 2006 Title Notes on the Terror Film Author Keith Hennessey Brown Publication FORUM: University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue Number 02 Issue Date Spring 2006 Publication Date 05/06/2006 Editors Joe Hughes & Beth Schroeder FORUM claims non-exclusive rights to reproduce this article electronically (in full or in part) and to publish this work in any such media current or later developed. The author retains all rights, including the right to be identified as the author wherever and whenever this article is published, and the right to use all or part of the article and abstracts, with or without revision or modification in compilations or other publications. Any latter publication shall recognise FORUM as the original publisher. FORUM ‘Fear and Terror’ 1 1 Notes on the Terror Film Keith Hennessey Brown (University of Edinburgh) Horror is, without question, among film's most enduring genres; audiences in search of thrills have been able to find a chiller to attend since the turn of the century. Even the studio of film pioneer Thomas Edison produced a 16-minute version of the Frankenstein story in 1910. The remarkable longevity of the genre does not, however, guarantee that a near century's worth of fans have all been lining up for the same motion picture show. (Lake Crane: 23) As Jonathan Lake Crane's perceptive comments indicate, the horror film is a remarkably resilient and adaptable film genre, one that has been able to meet the needs of successive generations of audiences in a way that others, like musicals and westerns, apparently have not, in the light of their declining production in recent decades. -

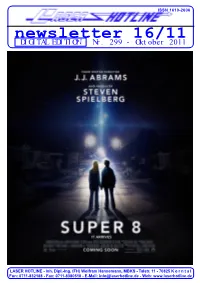

Newsletter 16/11 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 16/11 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 299 - Oktober 2011 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 16/11 (Nr. 299) Oktober 2011 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, Interest” auf einen anderen Newsletter Festivalprogramm der Schauburg in liebe Filmfreunde! zu verschieben. Auch “Wolfram Hanne- Karlsruhe, das wir ab Seite 4 für Sie manns Film-Blog” musste der giganti- aufbereitet haben. Auch wenn wir in Wie bereits in Newsletter Nr. 298 ange- schen Anzahl angekündigter amerikani- dieser Newsletter-Ausgabe aus Platz- droht, finden Sie in der vorliegenden scher Neuerscheinungen weichen und gründen fast komplett auf Grafiken ver- Ausgabe ausschließlich amerikanische wird erst wieder in Ausgabe 300 er- zichtet haben, lohnt sich ein Blick in DVDs und Blu-rays. Auch wenn der scheinen. Dafür aber haben wir den die Release-Liste aus Amerika. Wie Newsletter damit auf über 70 Seiten versprochenen Bericht vom 25. Fantasy immer wünschen wir viel Spaß beim gewachsen ist, konnten wir dennoch Filmfest ab Seite 9 abgedruckt. Und für Stöbern! nicht alle US-Releases integrieren. Wir Freunde breitformatiger Kinounter- haben uns daher entschieden, die bei- haltung empfiehlt sich ein Blick in das Ihr Laser Hotline Team den Kategorien “Music” und “Special LASER HOTLINE Seite 2 Newsletter 16/11 (Nr. 299) Oktober 2011 IbuproLOL Der Altweibersommer herrscht noch in Zürich, aber Playmobil und Modellflugzeuge interessieren, bis zu die Viren haben sich nicht lumpen lassen: Es ist den billigen Special Effects – hier wurde nicht ge- Herbst und der Frontalangriff hat stattgefunden. -

Shock Entertainment Dealer Guide February 2019

DEALER GUIDE FEBRUARY 2019 RISE CERTAIN WOMEN FRIGHT NIGHT HIDEAWAY U TURN COVER TITLE: RISE DEALER GUIDE CONTENTS 03 RISE 04 CERTAIN WOMEN 05 FRIGHT NIGHT 06 HIDEAWAY 07 U TURN 08 PEGGY SUE GOT MARRIED 09 THE MEDALLION 10 DID YOU HEAR ABOUT THE MORGANS? 11 MAID IN MANHATTAN 12 MONA LISA SMILE 13 MARY REILLY 14 ALL THE PRETTY HORSES 15 LOST IN ALASKA 16 KEEP 'EM FLYING 17 IT AIN'T HAY 18 HERE COME THE CO-EDS 19 THE WISTFUL WIDOW WWW.SHOCK.COM.AU RISE RELEASE DATE 06.02.19 RISE DARE TO DREAM. Rise is a heartening new drama about finding inspiration in unexpected places. When dedicated teacher and family man Lou Mazzuchelli (Josh Radnor) sheds his own self-doubt and takes over the school's lackluster theater department, he galvanizes not only the faculty and students, but the entire working-class town. Inspired by a true story. SALES & MARKETING ARTWORK TBC KEY SELLING POINTS SPECS • From the producers of Friday Night Lights, Parenthood and Hamilton. LABEL: SHOCK •‘ Stars How I Met Your Mother’ Josh Radner and the talented Auili’I Cravalho, who is known for voicing Moana from Disney’s film of the same name. RATING: TBA • The series also stars Oscar Nominee Rosie Perez known for White Men Can’t Jump, as well as Shannon DISCS: 3 DVDS Purser from Stranger Things, Riverdale and Sierra Burgess is a Loser. RUN TIME: 450 MINS • Rise has been praised as “heartfelt from start to finish” (Uncle Barky) and a show that is “…up there as one SOUND: 5.1 of the best new shows, and that’s down to the first class acting, relatable characters and an exciting subject REGION: 4 matter.” (TV Fanatic). -

Download Reading Copy

Smithsonian Depositions and Subject to a Film Clark Coolidge First published by Vehicle Editions (New York) in 1980. [Reading Copy Only: facsimile available at http://english.utah.edu/eclipse] SMITHSONIAN DEPOSITIONS . and it is a place in a state, a book, a movie like any other. The back of a dry goods house on Wop Hill, the sun coming through the bushes. The doctor moves a bit in his car rolling past, or is it through?, the outskirts. And the Great Quarry of Leach enclosed in no way an appropriate setting, abutted upon noone in any manner. A feldspar in red leaves. The pool is blue in green in white rim-cupped edges. The oranges are loose. Walking the picket wall along, a man whose thoughts twitch as billboards blank the light. It's a gnat, its pulse, a nylon purse under ultraviolet fixture in daylight. Even the large houses are small, inside the television a blue in grey. A football star with "Glass" on his jersey back. Nothing is lacking nor waiting for the fire in the grate, the mumbles over walnuts, the glance past an andiron. I have gone here to come away glanced, and moved upon. And a grasshopper of red basalt, boot-long, tumbles from the core of his mind, a rubble-bank disintegrating beneath a tropic downpour. Then Passaic Center loomed like a dull adjective. Each "store" in it was an adjective unto the next, a chain of adjectives disguised as stores. One second I was born, and then found that I lived there. The trees have been red so long that many feel it will never rain again.