Rediscovering Utopia, by Dougal Mcneill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of the Unite Union in New Zealand by Mike Treen Unite National Director April 29, 2014

AA shortshort historyhistory ofof thethe UniteUnite UnionUnion inin NewNew ZealandZealand ByBy MikeMike TreenTreen ! A short history of the Unite Union in New Zealand By Mike Treen Unite National Director April 29, 2014 SkyCity Casino strike 2011 ! In the late 1980s and early 1990s, workers in New union law. When the Employment Contracts Act was Zealand suffered a massive setback in their levels made law on May Day 1990, every single worker of union and social organisation and their living covered by a collective agreement was put onto an standards. A neo-liberal, Labour Government elected individual employment agreement identical to the in 1984 began the assault and it was continued and terms of their previous collective. In order for the deepened by a National Party government elected in union to continue to negotiate on your behalf, you 1990. had to sign an individual authorisation. It was very difficult for some unions to manage that. Many The “free trade”policies adopted by both Labour were eliminated overnight. Voluntary unionism was and the National Party led to massive factory introduced and closed shops were outlawed. All of closures. The entire car industry was eliminated and the legal wage protections which stipulated breaks, textile industries were closed. Other industries with overtime rates, Sunday rates and so on, went. traditionally strong union organisation such as the Minimum legal conditions were now very limited - meat industry were restructured and thousands lost three weeks holiday and five days sick leave was their jobs. Official unemployment reached 11.2% in about the lot. Everything else had to be negotiated the early 1990s. -

Fisheries Policy Maori and the Future of Fishing

Horizon Research Fisheries Policy Maori and the future of fishing June 2019 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ 1 1. Awareness of the QMS ................................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. 2. Little agreement with arguments for the QMS ........................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3. Arguments against the QMS ....................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 4. Agreement on proposed policies ............................................................................................. 14 5. Strong agreement for reform ................................................................................................... 18 6. Strong agreement for further work by the Government ......................................................... 21 7. Impact on party and candidate voting ..................................................................................... 23 APPENDIX 1 – METHODOLOGY AND SAMPLE ....................................................................................... 28 APPENDIX 2 - ELECTORATE GROUPS ..................................................................................................... 29 APPENDIX 3 – TABLES ........................................................................................................................... 30 Horizon Research Limited PO Box 52-107 Kingsland 1352. Telephone 021 84 85 -

Memorandum of Understanding Between The

Memorandum Of Understanding As at Sunday 25th May 2014 Between the MANA Movement and the Internet Party The Parties Agree: A: Registration 1. To register a new political party (referred to herein as the ‘New Party’) and for the Internet Party and MANA Movement (herein referred to as the ‘component parties’) to provide 275 names and written authorities (if required) of existing or new members to become founding members of the New Party. 2. To develop a constitution, candidate selection rules and logo for the New Party that reflects the principles of the relationship and this agreement. 3. To submit a complete application for registration of the New Party in early June 2014. 4. To inform the Electoral Commission that the component parties will be component parties of the New Party. B: Name and Logo 5. The full name of the New Party will be ‘Internet Party and MANA Movement’ and short name ‘Internet MANA’. 6. That both parties will work collaboratively to develop a logo for the New Party which will be a composite formed by the Internet Party’s logo and a new logo for MANA. If the Electoral Commission does not approve this logo, both parties will work together to develop an acceptable one using the principle of equal partnership. C: Leadership, Spokespeople and Party Roles 7. To establish a joint New Party Council to make decisions on behalf of the New Party with four representatives from each component party, including: a). Hone Harawira MP as the founding Leader of the New Party. b). The leader of the Internet Party as Chairperson of the New Party Council. -

Inequality and the 2014 New Zealand General Election

A BARK BUT NO BITE INEQUALITY AND THE 2014 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION A BARK BUT NO BITE INEQUALITY AND THE 2014 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION JACK VOWLES, HILDE COFFÉ AND JENNIFER CURTIN Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Vowles, Jack, 1950- author. Title: A bark but no bite : inequality and the 2014 New Zealand general election / Jack Vowles, Hilde Coffé, Jennifer Curtin. ISBN: 9781760461355 (paperback) 9781760461362 (ebook) Subjects: New Zealand. Parliament--Elections, 2014. Elections--New Zealand. New Zealand--Politics and government--21st century. Other Creators/Contributors: Coffé, Hilde, author. Curtin, Jennifer C, author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2017 ANU Press Contents List of figures . vii List of tables . xiii List of acronyms . xvii Preface and acknowledgements . .. xix 1 . The 2014 New Zealand election in perspective . .. 1 2. The fall and rise of inequality in New Zealand . 25 3 . Electoral behaviour and inequality . 49 4. The social foundations of voting behaviour and party funding . 65 5. The winner! The National Party, performance and coalition politics . 95 6 . Still in Labour . 117 7 . Greening the inequality debate . 143 8 . Conservatives compared: New Zealand First, ACT and the Conservatives . -

E-Whanaungatanga : the Role of Social Media in Māori Political Engagement

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. E-whanaungatanga: The role of social media in Māori political engagement A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Development Studies at Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa: Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand. Joanne Helen Waitoa 2013 Abstract Social media are used increasingly worldwide to connect people and points of view. This thesis explores the role social media can play in enhancing Māori development via political engagement. It investigates the efficacy of using social media to increase Māori political awareness and participation using the Mana Party Facebook pages as a case study. It also examines the opportunities and implications of social media for indigenous development in general. Themes in the literature on social media and indigenous development include: identity politics; language revitalisation and cultural preservation; activism; knowledge management; networking and collaboration; and business and marketing. This qualitative study was informed by Kaupapa Māori and empowerment theories. It involves interviews with the Mana Party president, Mana Party Facebook page moderators, and users of the Mana Party Facebook pages. The interviews explored the objectives and outcomes of using social media to raise political awareness of Māori, finding that Mana Party objectives were met to varying degrees. It also found that social media has both positive and negative implications for indigenous development. -

Waitoa, Joanne

The role of social media in Māori political engagement Joanne Waitoa Institute of Development Studies, Massey University .How can social media conscientize and mobilize Māori to engage with politics? .How can social media be used to advance indigenous development? . Theorists - G. Smith (1997); L. Tuhiwai-Smith (1999), Bishop (1999), Pihama (2001). “Intrinsic to Kaupapa Māori theory is an analysis of existing power structures and societal inequalities…exposing underlying assumptions that serve to conceal the power relations that exist within society and the ways in which dominant groups construct conceptions of ‘common sense’ and ‘facts’ to provide ad hoc justification for the maintenance of inequalities and the continued oppression of Māori” (Pihama cited in Cram, 2001, p.40). Facebook Engagement with Mana Party Post Share Comment Like Read 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Type of engagement Type Number of participants 13 semi structured interviews: Mana party president Annette Sykes, two Mana ki Manawatū Facebook page moderators, 10 members of Facebook pages - Mana Movement, Mana Rangatahi, Mana ki Manawatū and Mana Wairarapa . Whanaungatanga (relationships): building and maintaining social and cultural networks, increasing solidarity within and among indigenous movements. Tino Rangatiratanga (self-determination): maintaining control over Māori representation, space to disseminate Māori perspectives and encourage discussion. “It’s really awesome to know that there are nations and groups of people who are going through what Māori are going through and that there’s solidarity around these issues. Not only just with indigenous people but heaps of Pākehā people out there”. “It helps us keep in touch with our whānau we haven’t heard from in years, or friends. -

Fightback 2014 Issue #6

Publication information Becoming a sustaining subscriber Table of Subscriptions to Fightback are avail- able for $20 a year, this covers the costs Contents of printing and postage. At present the writing, proof reading, layout, and 3 Editorial distribution is all done on a volun- teer basis. To make this publication 4 National and its right wing friends sustainable long term we are asking for people to consider becoming ‘Sustain- 7 The politics, not the dirt is the problem ing subscribers’ by pledging a monthly amount to Fightback (suggested $10). 8 Whale Oil leaks: Anti-politics from above Sustaining subscribers will be send a free copy of each of our pamphlets to 12 Rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic? thank them for their extra support. To start your sustaining subscription set The Labour Party and MANA up an automatic payment to 38-9002- 0817250-00 with your name in the 14 Hone Harawira: Burning the flag or accepting particulars and ‘Sustain’ in the code the evil and email your name and address to [email protected] 15 Regional Joint Statement 15 New Zealand state’s quandary in the Asia- Pacific 18 Unite against poverty wages and zero-hour Get Fightback contracts: An interview with Heleyni Pratley each month 19 Elections and migrant-bashing: Full rights for Within NZ: $20 for one year (11 issues) migrant workers or $40 for two years (22 issues) Rest of the World: $40 for one year or 21 Miriam Pierard of the Internet Party: “Speak- $80 for two years ing the language of youth” Send details and payments to: Fightback, PO Box 10282 27 Coalition governments and real change Dominion Rd, Auckland or Bank transfer: 38-9002-0817250-01 Donations and bequeathments Fightback is non-profit and relies on financial support from progressive people, supporters and members for all its activities including producing this magazine. -

Representation of Asians in Media Coverage of the 2014 New Zealand General Election

Financially important yet voiceless: Representation of Asians in media coverage of the 2014 New Zealand General Election. Craig Hoyle A dissertation submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Communication Studies (BCS) (Hons) 2014 School of Communication Studies HOYLE Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………....………… 5 2. Literature Review…………………………... 6 3. Research Design……………………………. 10 4. Findings……………………………………. 14 5. Discussion………………………………….. 18 6. Conclusion…………………………………. 23 7. Limitations/Future Research……………….. 24 8. References………………………………….. 26 9. Appendices…………………………………. 33 List of Tables 1. Reference to Social Groups by Ethnicity, Race, Nationality (ERN) ……………………….14 2. Comparison of topics between Whole Sample and Asian Sample ……………………….16 3. Comparison of Political Sources between Whole Sample and Asian Sample ……………………….17 2 HOYLE I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person (except where explicitly defined in the acknowledgements), nor material which to a substantial extent has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma or a university or other institution of higher learning. ………………………………… Craig Hoyle 3 HOYLE Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr Verica Rupar for her valuable assistance in supervising this research project. Dr Josè del Pozo Cruz’s help and advice in the use of SPSS was also very much appreciated. Finally, thanks must go to the AUT DCT Strategic Fund for sponsoring the wider research project within which this dissertation occurred. 4 HOYLE Abstract: Asian communities have been part of New Zealand society since the mid-19th Century. -

Māori Participation and Representation

Māori Participation and Representation: An Investigation into Māori reported experiences of Participation and Representation within the policy process post-MMP _____________________________________ A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Josephine Clarke _______________________________________ University of Canterbury 2015 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABSTRACT iv LIST OF TABLES v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS vi GLOSSARY vii CHAPTER ONE Introduction and Literature Review 1 CHAPTER TWO Methodology 23 CHAPTER THREE Foreshore and Seabed Act 2004 37 CHAPTER FOUR Marine and Coastal (Takutai Moana) Act 2011 65 CHAPTER FIVE Whānau Ora 86 CHAPTER SIX Conclusion 108 APPENDECIES A Māori Research Advisory Group Form 135 B Unstructured Interview Prompts 137 C Information Sheet 138 D Consent Form 140 E Regional Boundaries 142 BIBLIOGRAPHY 143 iii Acknowledgements There are a number of people and organizations that I would like to thank for their assistance during the writing of this thesis. Most importantly I would like to extend my gratitude all those who imparted their individual knowledge, experiences, perceptions and wisdom to this research as participants. I am especially grateful to Sue Rudman, the Bream Bay Trust and all the E Tu Whānau team who took me to Waitangi and facilitated not only countless interviews, but also gave me a remarkable experience of seeing Whānau Ora funding in action. Similarly I would like to thank another person, who wishes to remain anonymous, who went above and beyond to assist a fellow student in facilitating countless invaluable interviews within the South Island. Thanks also to Lindsay Te Ata o Tu MacDonald, Ripeka Tamanui-Hurunui and Abby Suszko for providing cultural guidance. -

Māori Opposition to Fossil Fuel Extraction in Aotearoa New Zealand

MĀORI OPPOSITION TO FOSSIL FUEL DEVELOPMENT IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND ZOLTÁN GROSSMAN The Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington Opposition has intensified in the past five years in Aotearoa New Zealand to foreign corporate deep-sea oil exploration, which opponents view as a threat to fisheries, beaches, tourism, marine mammals, and climate stability. Opponents fear that an oil spill the scale of the Exxon or BP disasters would overwhelm the country’s economy and government’s capacity for clean-up. Despite interest in oil revenues from a few local Māori leaders, growing numbers of Māori are beginning to view oil drilling as a challenge to the Treaty of Waitangi, and proclaim that “Aotearoa is Not for Sale.” I visited Aotearoa for two months earlier this year, as part of my study abroad class “Native Decolonization in the Pacific Rim: From the Northwest to New Zealand,” which I have taught this past year (with my colleague Kristina Ackley) at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington.1 We joined fifteen of our undergraduate students, half of them Indigenous and half non-Native, in the journey to visit Māori and Pasifika (Pacific Islander) communities throughout North Island, and to conduct research projects comparing Pacific Northwest treaty rights and tribal sovereignty to the Treaty of Waitangi and Māori self-determination. It was the second class we took to Aotearoa, building on previous exchanges of Indigenous artists through our campus Longhouse, and graduate students through our Tribal Master’s of Public Administration program. When the students were off doing their projects, and I was visiting with them, I conducted my own research on Māori alliances with Pākehā (European settlers) in the movement against oil drilling, as well as the political intersections between fossil fuel extraction and Māori decolonization. -

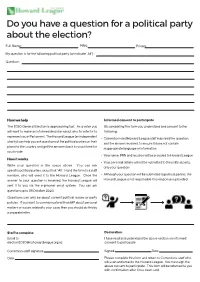

Do You Have a Question for a Political Party About the Election?

Do you have a question for a political party about the election? Full Name: PRN: Prison: My question is for the following political party (or indicate “All”) : Question: How we help Informed consent to participate The 2020 General Election is approaching fast. As a voter you By completing this form you understand and consent to the will want to make an informed decision about who to vote for to following: represent you in Parliament. The Howard League (an independent • Corrections and Howard League staff may read the question, charity) can help you ask questions of the political parties on their and the answer received, to ensure it does not contain plans for the country, and get the answers back to you in time for inappropriate language or information you to vote. • Your name, PRN and location will be provided to Howard League How it works • Your personal details will not be submitted to the political party; Write your question in the space above. You can ask only your question specific political parties, or just tick “All”. Hand the form to a staff member, who will send it to the Howard League. Once the • Although your question will be submitted to political parties, the answer to your question is received, the Howard League will Howard League is not responsible if no response is provided sent it to you via the e-prisoner email system. You can ask questions up to 09 October 2020. Questions can only be about current political issues or party policies. If you want to communicate with an MP about personal matters or issues related to your case, then you should do this by a separate letter. -

Aotearoa+Not+For+Sale+Leaflet

Aotearoa Not For Sale To local or foreign Capitalists! Workers Party members are actively sup- state housing sell-offs is another inspiring porting the “Aotearoa is not for sale” hīkoi. example. Indeed, we believe we need to go further than just keeping assets in public hands, We must also guard against the strong we want to push forward for workers’ and element of xenophobia around “foreign users’ control of those assets. ownership”, particularly against Chinese ownership of NZ assets. We in the Work- Whilst a number of political parties have ers Party are socialists and international- pledged their support for the campaign, ists, and regard the arguments about “for- we must be on guard that the campaign eign ownership” as a dangerous distraction does not become side tracked by an exces- that threatens to undermine our struggle sively Parliamentary focus. The ongoing against privatisation. The problem is pri- struggle of the Auckland wharfies against vate capitalist ownership of public utili- casualisation (the first step towards priva- ties, whether those capitalists are New tisation) shows the most effective way to Zealanders or “foreigners”. oppose the government’s asset sales plan. The last thing capitalist investors want Furthermore, there is a particularly nasty to deal with is a bolshy workforce. The history of anti-Chinese racism in New campaign by Glen Innes residents against Zealand, which dates to the development of immigration controls in this country. We support the actions of Ngāti Rereahu Immigration controls originated from a who occupied one of the Crafar farms in “White New Zealand Policy” that was February, demanding the return of their initially concerned with keeping out Chi- ancestral whenua.