Torn Between Chromophobia and Colour Mania – Developments of Early Technicolor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

Ijmberland Island '** WITU/ITHU Whicu/Uirhu Iisc Consolidaterntwcni Rnatrdn THTUEP CUMBERLANPI IMRPPI Anidn NEWSNFWS

ll f0+000000000000000a*0000000000000004 I 0000000000000000000000000000000000^ TALKING At the Ilo-Ilo PICTURES all next Week ^,$^000000000000000000000000000000* ijmberland Island '** WITU/ITHU WHICu/uirHu IiSc CONSOLIDATErntwcni rnATrDn THTUEP CUMBERLANPI IMRPPI ANiDn NEWSNFWS . FORTY-NINTH YEAR— No. 6 CUMBERLAND, BRITISH COLOMBIA FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 7th, 1980 HCHSCKII'TION PRICE: TWO DOLLARS PER ANNUM |MR. FRANK FIDDLER Home Economics SCHOOL TRUSTEES Pattullo's Expenses WILL DELIVER ADDRESS IN MONTHLY MEETJ Disappearance Of i Father an Son Banquet at United Pupils Exhibit REPORT OF APPS ON RECENT Church VISIT TO CITY SCHOOLS Their Ability BEFORE BOARD In Campaign From ! Mr. Frank Fiddler, bachelor of J. Ramsay Causes ! science of Vancouver who has charge SCHOOL BO^RD MEMBERS EN The regular monthly meeting of; : of the boys' woik in B. C. will | TERTAINED AT DINNER Lhe Cumberland School Trustees was j ; deliver an address on conclusion ofl held in the school on Thursday night ! Provincial Treasury ithe 7 o'clock service at Ihe ('umber-, Pupils of Miss I). Cannon, home with Mrs. MacNaughton in the chair Anxiety to Friends | land United Church, Sunday. This J economics teacher, demonstrated! and trustees Baird and Partridge and DOINGS AT THE CAPITAL AS SEEN AND NOTED BY OUR ! service will be conducted by the boys' their ability in the art of cooking on McKimi'in present. Many communi i and the choir will be composed of Monday night, when the members of cations were before the board, Missj NO TRACE FOUND OF WELL-KNOWN MAN; MISSING OWN CORRESPONDENT l men and boys connected with boys the Cumberland School Board were McFadyen thanking the trustees for SINCE MONDAY MORNING j work in Cumberland. -

Opening Pandora's Box BFI Uncovers Rare Technicolor Footage of Louise

The American Venus (1926), Source: BFI National Archive/Paramount Pictures Opening Pandora’s Box BFI uncovers rare Technicolor footage of Louise Brooks in living colour For Immediate release: 30 April 2018, London The BFI today announces the discovery of a cache of extremely rare Technicolor film fragments from the 1920s held by the BFI National Archive, including previously unseen footage of Louise Brooks dancing in colour. The very image of the modern woman, this tantalising glimpse of Louise Brooks comes from The American Venus (1926), her first credited film role and is one of the only images we have of her in colour. The feature is believed lost with the exception of footage from the film’s trailer, held by Berkeley Art Museum and The Library of Congress. It is thought that this extremely short extract discovered by the BFI may come from a costume test. The fragment from The American Venus (1926) was found alongside material from The Far Cry (1926), The Fire Brigade (1926) and Dance Madness (1926) within a copy of Black Pirate (1926), donated to the Archive by The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in 1959. In the same print of Black Pirate, there is also a test shot for historical drama Mona Lisa (1926) starring Hedda Hopper, the ‘Queen of the Quickies’ and legendary acerbic Hollywood gossip columnist for the LA Times, whose biting wit was recently portrayed by Judy Davis in award-winning TV series Feud. The fragment shows Hedda Hopper as Mona Lisa in repose, one assumes, about to be painted by Leonardo da Vinci. -

Yagenich L.V., Kirillova I.I., Siritsa Ye.A. Latin and Main Principals Of

Yagenich L.V., Kirillova I.I., Siritsa Ye.A. Latin and main principals of anatomical, pharmaceutical and clinical terminology (Student's book) Simferopol, 2017 Contents No. Topics Page 1. UNIT I. Latin language history. Phonetics. Alphabet. Vowels and consonants classification. Diphthongs. Digraphs. Letter combinations. 4-13 Syllable shortness and longitude. Stress rules. 2. UNIT II. Grammatical noun categories, declension characteristics, noun 14-25 dictionary forms, determination of the noun stems, nominative and genitive cases and their significance in terms formation. I-st noun declension. 3. UNIT III. Adjectives and its grammatical categories. Classes of adjectives. Adjective entries in dictionaries. Adjectives of the I-st group. Gender 26-36 endings, stem-determining. 4. UNIT IV. Adjectives of the 2-nd group. Morphological characteristics of two- and multi-word anatomical terms. Syntax of two- and multi-word 37-49 anatomical terms. Nouns of the 2nd declension 5. UNIT V. General characteristic of the nouns of the 3rd declension. Parisyllabic and imparisyllabic nouns. Types of stems of the nouns of the 50-58 3rd declension and their peculiarities. 3rd declension nouns in combination with agreed and non-agreed attributes 6. UNIT VI. Peculiarities of 3rd declension nouns of masculine, feminine and neuter genders. Muscle names referring to their functions. Exceptions to the 59-71 gender rule of 3rd declension nouns for all three genders 7. UNIT VII. 1st, 2nd and 3rd declension nouns in combination with II class adjectives. Present Participle and its declension. Anatomical terms 72-81 consisting of nouns and participles 8. UNIT VIII. Nouns of the 4th and 5th declensions and their combination with 82-89 adjectives 9. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016" (2016). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 73. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/73 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1. SPRING, 2016 TSA Board Member and Newsletter Editor Wendy Weiss behind the scenes at the UCB Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, durring the TSA Board meeting in March, 2016 Spring 2016 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (Membership & Communications Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

Tyrian Purple: Its Evolution and Reinterpretation As Social Status Symbol During the Roman Empire in the West

Tyrian Purple: Its Evolution and Reinterpretation as Social Status Symbol during the Roman Empire in the West Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Graduate Program in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Andrew J. Koh, Advisors In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies by Mary Pons May 2016 Acknowledgments This paper truly would not have come to be without the inspiration provided by Professor Andrew Koh’s Art and Chemistry class. The curriculum for that class opened my mind to a new paradigmatic shift in my thinking, encouraging me to embrace the possibility of reinterpreting the archaeological record and the stories it contains through the lens of quantifiable scientific data. I know that I would never have had the courage to finish this project if it were not for the support of my advisor Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, who never rejected my ideas as outlandish and stayed with me as I wrote and rewrote draft after draft to meet her high standards of editorial excellence. I also owe a debt of gratitude to my parents, Gary and Debbie Pons, who provided the emotional support I needed to get through my bouts of insecurity. When everything I seemed to put on the page never seemed good enough or clear enough to explain my thought process, they often reminded me to relax, sleep, walk away from it for a while, and try again another day. -

Copyrighted Material

335 Index a “After You Get What You Want, You “Aba Daba Honeymoon” 151 Don’t Want It” 167 ABBA 313 Against All Odds (1984) 300 Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein “Age of Not Believing, The” 257 (1948) 155 Aguilera, Christina 323, 326 Abbott, Bud 98–101, 105, 109, 115 “Ah Still Suits Me” 87 ABC 229–230 “Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life” 78 Abdul, Paula 291 AIDS 317–318 About Face (1953) 151 “Ain’t There Anyone Here for “Abraham” 110–111 Love?” 170 Absolute Beginners (1986) 299 Aladdin (1958) 181 Academy Awards 46, 59, 73–74, 78, 82, Aladdin (1992) 309–310, 312, 318, 330 89, 101, 103, 107, 126, 128, 136, 140, Aladdin II, The Return of Jafar 142, 148–149, 151, 159, 166, 170, 189, (1994) 309 194, 200, 230, 232–233, 238, 242, 263, Alamo, The (1960) 187 267, 271, 282, 284, 286, 299, 308–309, Alexander’s Ragtime Band (1938) 83, 319, 320–321 85–88 Ackroyd, Dan 289 Alice in Wonderland (1951) 148 Adler, Richard 148 Alice in Wonderland: An X‐Rated Admiral Broadway Revue (1949) 180 Musical Fantasy (1976) 269 Adorable (1933) 69 All‐Colored Vaudeville Show, An Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the (1935) 88 Desert, The (1994) 319 “All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm” 88–89 African AmericansCOPYRIGHTED 13–17, 21, 24, 28, 40, All New MATERIAL Mickey Mouse Club, The 43, 54–55, 78, 87–89, 109–111, 132, (1989–94) 326 163–164, 193–194, 202–203, 205–209, “All Out for Freedom” 102 213–216, 219, 226, 229, 235, 237, All‐Star Revue (1951–53) 179 242–243, 258, 261, 284, 286–287, 289, All That Jazz (1979) 271–272, 292, 309, 293–295, 314–315, 317–319 320, 322 “After the Ball” 22 “All You Need Is Love” 244 Free and Easy? A Defining History of the American Film Musical Genre, First Edition. -

DA Classical & Popular Erolls.Xlsx

E-roll files include three test roll files Duo-Art Popular MIDI and e-roll files Total MIDI files = 637 Title order Total e-roll files = 640 Title Writer(s) Pianist Roll # Date timemidi file name A Dream Bartlett Arndt 100455 01 1920 2:48 A Dream (Bartlett) Arndt DA Absent Metcalf Rapee 100925 09 1921 2:16 Absent (Metcalf) Rapee DA After My Laughter Came Tears Turk Headden 0860 br 1928 by 2:31 After Laughter Came Tears DA Afternoon Of A Fox (Foxtrot) Bentz Bentz 1539 06 1917 3:37 Afternoon of Fox (Bentz), Bentz DA Ah Ha Monaco Moran 713125 08 1925 2:36 Ah Ha, Moran DA Ah Sweet Mystery of Life from Herbert Armbruster 103616 04 1928 3:43 Ah Sweet Mystery (Herbert) Armbrstr DA “Naughty Marietta” Ah, Moon of My Delight "from "In a Lehmann Armbruster 102725 11 1925 6:43 Ah, Moon of Delight, Armbrstr DA Persian Garden" Erlbach & Ain’t You Coming Back to Dixieland Whiting 1545 09 1817 2:54 Ain't Back to Dixieland DA Gershwin Ain't Misbehavin' Waller & Brooks Jay 668 11 1929 2:36 Ain't Misbehavin, Jay DA Ain't She Sweet Ager Alpert 713367 05 1927 2:51 Ain't She Sweet, Alpert DA Alabamy Bound Henderson Rich 713098 05 1925 3:58 Alabamy Bound, Rich DA Alice Blue Gown and Sweetheart Tierney-Romberg Rapee 6469 09 1921 3:53 Alice Blue Gown, Sweetheart DA All Alone from "Music Box Review of Berlin Armbruster 102395 06 1926 4:17 All Alone (Berlin), Armbrstr DA 1924" All Alone from "Music Box Revue of Berlin Wehrlen 713051 01 1925 2:25 All Alone (Berlin) Wehrlen DA 1924" All Alone With You (In a Little Snyder Rich & Milne 713032 11 1924 3:21 All Alone -

Reconstructing American Historical Cinema This Page Intentionally Left Blank RECONSTRUCTING American Historical Cinema

Reconstructing American Historical Cinema This page intentionally left blank RECONSTRUCTING American Historical Cinema From Cimarron to Citizen Kane J. E. Smyth THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2006 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smyth, J. E., 1977- Reconstructing American historical cinema : from Cimarron to Citizen Kane / J. E. Smyth. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8131-2406-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8131-2406-9 (alk. paper) 1. Historical films--United States--History and criticism. 2. Motion pictures and history. I. Title. PN1995.9.H5S57 2006 791.43’658--dc22 2006020064 This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. Manufactured in the United States of America. Member of the Association of American University Presses For Evelyn M. Smyth and Peter B. Smyth and for K. H. and C. -

Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-De-Siècle France

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Art History Theses and Dissertations Art History Spring 5-15-2021 Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-de-Siècle France Ana Norman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/arts_arthistory_etds Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Norman, Ana, "Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-de-Siècle France" (2021). Art History Theses and Dissertations. 7. https://scholar.smu.edu/arts_arthistory_etds/7 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. MIMING MODERNITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF PIERROT IN FIN-DE-SIÈCLE FRANCE Approved by: _______________________________ Dr. Amy Freund Associate Professor of Art History _______________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Eager Assistant Professor of Art History _______________________________ Dr. Randall Griffin Distinguished Professor of Art History !"Doc ID: ec9532a69b51b36bccf406d911c8bbe8b5ed34ce MIMING MODERNITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF PIERROT IN FIN-DE-SIÈCLE FRANCE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Meadows School of the Arts Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Art History by Ana Norman B.A., Art History, University of Dallas May 15, 2021 Norman, Ana B.A., Art History, University of Dallas Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-de-Si cle France Advisor: Dr. Amy Freund Master of Art History conferred May 15, 2021 Thesis completed May 3, 2021 This thesis examines the commedia dell’arte character Pierrot through the lens of gender performance in order to decipher the ways in which he complicates and expands understandings of gender and the normative model of sexuality in fin de siècle France. -

Legal Protection for Literary Titles

6 Legal Protection for Literary Titles A Marxist Case Study Terence P. Ross 946 was a great year for the motion Our Lives – are on the American Film In- picture industry in the United States and stitute’s list of the 100 Greatest Movies. But for movie goers. With the repeal of the at least ten more films from 1946 would be wartime excess profits tax, total net industry recognized by critics and film-goers of today 1profits after taxes soared from $89 million in as classics, still well worth viewing.2 These 1945 to $190 million in 1946. Equally impres- include: sive, 4.7 billion movie tickets were sold in the Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, starring United States, making 1946 Hollywood’s all- Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman; time peak attendance year.1 And, although John Ford’s My Darling Clementine, some might be tempted to attribute these starring Henry Fonda; increases to the expansion of the movie- Charles Vidor’s Gilda, starring Rita going public with the return of soldiers, sail- Hayworth and Glenn Ford; ors and marines from overseas, the more Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always likely reason is simply the phenomenal qual- Rings Twice, starring Lana Turner and ity of movie offerings in 1946. John Garfield; Two films released in 1946 – Frank Cap- Clarence Brown’s The Yearling, starring Gregory Peck and Jane Wyman; ra’s Christmas classic, It’s A Wonderful Life, and William Wyler’s drama of war veterans King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun, starring Joseph Cotton, Gregory Peck and Lio- adjusting to civilian life, The Best Years Of nel Barrymore; Terence Ross is a partner in the Washington, DC, office of Gibson, Dunn s Crutcher LLP engaged in the practice of intellectual property law. -

People with the Fear of Colors Tend to Suffer from Many Debilitating

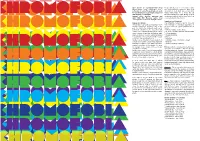

CHROMOFOBIA (also known as chromatophobia) (from People with the fear of colors tend to suffer Greek chroma, “color” and phobos, “fear”) from many debilitating symptoms. Often, they is the fear of colors.The worst place to be in are unable to hold down jobs or even have CHROMOFOBIA for chromophobes is Las Vegas because of steady relationships. As a result, life can CHROMOFOBIA their brightly colored lights. become miserable for them. Going outdoors Famous actor, director, musician and can become a difficult task for them, for the fear writer Billy Bob Thornton suffers from of encountering the hated colors. chromophobia, or the fear of bright colours. Symptoms and treatment Causes and effects The symptoms of effects of fear of color vary This phobia is caused by post traumatic stress from individual to individual depending on CHROMOFOBIA disorder experiences involving colors in the the level of the fear. Typical symptoms are as CHROMOFOBIA past. An event in the childhood might lead to follows: permanent emotional scars associated with * Extreme anxiety or panic attack certain colors or shades which the phobic simply * Shortness of breath- rapid and shallow breaths cannot outgrow. Events like child abuse, rape, * Profuse sweating death, accidents or violence, could all be related * Irregular heartbeat to a particular color causing the phobic to panic * Nausea or become anxious in its presence. * Dry mouth CHROMOFOBIA Another cause of the fear of colors stems from * Inability to speak or formulate coherent cultural roots. Certain cultures have significant sentences CHROMOFOBIA meanings for specific colors which can have a * Shaking, shivering, trembling CHROMOFOBIA negative connotation for the phobic.