And Type the TITLE of YOUR WORK in All Caps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings First Annual Palo Alto Conference

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST ANNUAL PALO ALTO CONFERENCE An International Conference on the Mexican-American War and its Causes and Consequences with Participants from Mexico and the United States. Brownsville, Texas, May 6-9, 1993 Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site Southwest Region National Park Service I Cover Illustration: "Plan of the Country to the North East of the City of Matamoros, 1846" in Albert I C. Ramsey, trans., The Other Side: Or, Notes for the History of the War Between Mexico and the I United States (New York: John Wiley, 1850). 1i L9 37 PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST ANNUAL PALO ALTO CONFERENCE Edited by Aaron P. Mahr Yafiez National Park Service Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site P.O. Box 1832 Brownsville, Texas 78522 United States Department of the Interior 1994 In order to meet the challenges of the future, human understanding, cooperation, and respect must transcend aggression. We cannot learn from the future, we can only learn from the past and the present. I feel the proceedings of this conference illustrate that a step has been taken in the right direction. John E. Cook Regional Director Southwest Region National Park Service TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. A.N. Zavaleta vii General Mariano Arista at the Battle of Palo Alto, Texas, 1846: Military Realist or Failure? Joseph P. Sanchez 1 A Fanatical Patriot With Good Intentions: Reflections on the Activities of Valentin GOmez Farfas During the Mexican-American War. Pedro Santoni 19 El contexto mexicano: angulo desconocido de la guerra. Josefina Zoraida Vazquez 29 Could the Mexican-American War Have Been Avoided? Miguel Soto 35 Confederate Imperial Designs on Northwestern Mexico. -

Miguel Sky Walker Free Download Album Drivers & Music

miguel sky walker free download album Drivers & Music. Miguel - Sky Walker (ft. Travis Scott) [Single - MP3] 8/24/ · Miguel and Travis Scott soar on 'Sky Walker.' After a pretty quiet year, San Pedro singer Miguel is back with an atmospheric banger called 'Sky Walker.' Whether he's . Download Miguel - Sky Walker ft. Travis Scott for Android to miguel Songs. Miguel just drop is new single from his single entitled "Sky Walker", featured with "Travis Scott" to watch on blogger.com "Sky Walker" from the project "Te Lo Dije" The single "Sky Walker" is a part of the project "Miguel" entitled "TE LO DIJE" the release date of "Te Lo Dije" is expected the April 06, , the tracklist and lyrics are available here: TRACKLISt and LYRICS of Te Lo Dije. Miguel skywalker free mp3 download. After a pretty quiet year, San Pedro singer Miguel is back with an atmospheric banger called "Sky Walker. Either way, the force is with him on this brand new track, which features the enigmatic Travis Scott in a rare guest appearance. Now, Miguel and Travis have teamed up yet again, and to nobody's surprise, the instrumental is perfectly in keeping with Scott's perceived persona - low key, mysterious, slightly drugged out. However, there does remain a catch - as of now, the song is not officially released in North America, which considerably limits its reach. Yet somehow, many people have already been bumping this joint, so as they say, where there's a will there's a way. Miguel skywalker free mp3 download it's not exactly clear what sort of connection any of this has to Star Wars, "Sky Walker" works adequately as a double meaning, emphasizing the heights of a peak drug trip, miguel skywalker free mp3 download . -

Masculine Textualities: Gender and Neoliberalism in Contemporary Latin American Fiction

MASCULINE TEXTUALITIES: GENDER AND NEOLIBERALISM IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN FICTION Vinodh Venkatesh A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages (Spanish). Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Oswaldo Estrada, Ph.D. María DeGuzmán, Ph.D. Irene Gómez-Castellano, Ph.D. Juan Carlos González-Espitia, Ph.D. Alfredo J. Sosa-Velasco, Ph.D. © 2011 Vinodh Venkatesh ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT VINODH VENKATESH: Masculine Textualities: Gender and Neoliberalism in Contemporary Latin American Fiction (Under the direction of Oswaldo Estrada) A casual look at contemporary Latin American fiction, and its accompanying body of criticism, evidences several themes and fields that are unifying in their need to unearth a continental phenomenology of identity. These processes, in turn, hinge on several points of construction or identification, with the most notable being gender in its plural expressions. Throughout the 20th century issues of race, class, and language have come to be discussed, as authors and critics have demonstrated a consciousness of the past and its impact on the present and the future, yet it is clear that gender holds a particularly poignant position in this debate of identity, reflective of its autonomy from the age of conquest. The following pages problematize the writing of the male body and the social constructs of gender in the face of globalization and neoliberal policies in contemporary Latin American fiction. Working from theoretical platforms established by Raewyn Connell, Ilan Stavans, and others, my analysis embarks on a reading of masculinities in narrative texts that mingle questions of nation, identity and the gendered body. -

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In Love Beyonce BoomBoom Pow Black Eyed Peas Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Old Time Rock n Roll Bob Seger Forever Chris Brown All I do is win DJ Keo Im shipping up to Boston Dropkick Murphy Now that we found love Heavy D and the Boyz Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande and Nicki Manaj Let's get loud J Lo Celebration Kool and the gang Turn Down For What Lil Jon I'm Sexy & I Know It LMFAO Party rock anthem LMFAO Sugar Maroon 5 Animals Martin Garrix Stolen Dance Micky Chance Say Hey (I Love You) Michael Franti and Spearhead Lean On Major Lazer & DJ Snake This will be (an everlasting love) Natalie Cole OMI Cheerleader (Felix Jaehn Remix) Usher OMG Good Life One Republic Tonight is the night OUTASIGHT Don't Stop The Party Pitbull & TJR Time of Our Lives Pitbull and Ne-Yo Get The Party Started Pink Never Gonna give you up Rick Astley Watch Me Silento We Are Family Sister Sledge Bring Em Out T.I. I gotta feeling The Black Eyed Peas Glad you Came The Wanted Beautiful day U2 Viva la vida Coldplay Friends in low places Garth Brooks One more time Daft Punk We found Love Rihanna Where have you been Rihanna Let's go Calvin Harris ft Ne-yo Shut Up And Dance Walk The Moon Blame Calvin Harris Feat John Newman Rather Be Clean Bandit Feat Jess Glynne All About That Bass Megan Trainor Dear Future Husband Megan Trainor Happy Pharrel Williams Can't Feel My Face The Weeknd Work Rihanna My House Flo-Rida Adventure Of A Lifetime Coldplay Cake By The Ocean DNCE Real Love Clean Bandit & Jess Glynne Be Right There Diplo & Sleepy Tom Where Are You Now Justin Bieber & Jack Ü Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun Renegades X Ambassadors Hotline Bling Drake Summer Calvin Harris Feel So Close Calvin Harris Love Never Felt So Good Michael Jackson & Justin Timberlake Counting Stars One Republic Can’t Hold Us Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Ft. -

Riaa Gold & Platinum Awards

1/1/2015 — 12/31/2015 In 2015, RIAA certified 934 Digital Single Awards and 122 Album Awards. Complete lists of all album, single and video awards dating all the way back to 1958 can be accessed at riaa.com. 2015 RIAA GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS DIGITAL MULTI-PLATINUM SINGLE (324) Cert Date Title Artist Label Plat Level Rel. Date 7/27/2015 SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF CAPITOL RECORDS 2 2/14/2014 SUMMER 12/11/2015 SAY SOMETHING A GREAT BIG WORLD EPIC/BLACK MAGNETIC 5 9/6/2013 & CHRISTINA AGUILERA 12/2/2015 HELLO ADELE COLUMBIA/XL RECORDINGS 2 10/23/2015 12/2/2015 HELLO ADELE COLUMBIA/XL RECORDINGS 3 10/23/2015 12/2/2015 HELLO ADELE COLUMBIA/XL RECORDINGS 4 10/23/2015 4/30/2015 BEST DAY OF MY LIFE AMERICAN ISLAND 3 8/27/2013 AUTHORS 7/15/2015 HONEY, I’M GOOD ANDY GRAMMER S-CURVE RECORDS 2 8/5/2014 8/31/2015 HONEY, I’M GOOD ANDY GRAMMER S-CURVE RECORDS 3 8/5/2014 4/28/2015 BREAK FREE ARIANA GRANDE REPUBLIC RECORDS 3 7/3/2014 6/15/2015 PROBLEM ARIANA GRANDE REPUBLIC RECORDS 6 4/28/2014 8/25/2015 WAKE ME UP AVICII ISLAND 5 7/2/2013 8/25/2015 WAKE ME UP AVICII ISLAND 6 7/2/2013 7/27/2015 POMPEII BASTILLE VIRGIN RECORDS 5 5/28/2013 7/27/2015 POMPEII BASTILLE VIRGIN RECORDS 4 5/28/2013 7/8/2015 SHOWER BECKY G KEMOSABE RECORDS/ 2 9/2/2014 COLUMBIA 3/5/2015 DRUNK IN LOVE BEYONCE COLUMBIA 2 12/13/2013 3/5/2015 DRUNK IN LOVE BEYONCE COLUMBIA 3 12/13/2013 www.riaa.com GoldandPlatinum @RIAA @riaa_awards 2015 4/1/2015 DANCE (A$$) BIG SEAN GETTING OUT OUR DREAMS/ 3 10/24/2011 DEF JAM 4/1/2015 I DON’T F**K WITH YOU BIG SEAN DEF JAM 2 9/19/2014 9/15/2015 I DON’T F**K WITH YOU BIG SEAN DEF JAM 3 9/19/2014 12/17/2015 BLESSINGS BIG SEAN DEF JAM 2 1/30/2015 5/8/2015 BOYS ‘ROUND HERE (FEATURING BLAKE SHELTON WARNER BROS. -

Gender in the City: the Intersection of Capital and Gender Consciousness in Latin American Cinema

Gender in the City: The Intersection of Capital and Gender Consciousness in Latin American Cinema Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Rangel, Liz Consuelo Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:39:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194421 GENDER IN THE CITY: THE INTERSECTION OF CAPITAL AND GENDER CONSCIOUSNESS IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA By Liz Consuelo Rangel _____________________ Copyright © Liz Consuelo Rangel 2009 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN SPANISH In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2009 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Liz Consuelo Rangel entitled Gender in the City: The Intersection of Capital and Gender Consciousness in Latin American Cinema and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: May 29, 2009 Dr. Melissa Ann Fitch _______________________________________________________________________ Date: May 29, 2009 Dr. Laura Gutiérrez _______________________________________________________________________ Date: May 29, 2009 Dr. Malcolm Compitello Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

From Manchay Tiempo to 'Truth': Cultural Trauma and Resilience In

From Manchay Tiempo to ‘Truth’: Cultural Trauma and Resilience in Contemporary Peruvian Narrative Adriana Beatriz Rojas Hopatcong, New Jersey M.A., University of Virginia, 2010 B.A., American University, 2004 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese University of Virginia September 2014 Ricardo Padrón Fernando Operé María-Inés Lagos Jeffrey Olick ii iii Abstract From Manchay Tiempo to “Truth”: Cultural Trauma and Resilience in Contemporary Peruvian Narrative Adriana Beatriz Rojas Clashes between the Shining Path and counterinsurgency during Peru’s internal conflict left the scars of symbolic, physical, and sexual violence on civil society. Peruvian cultural production has since engaged the memory, trauma, and lasting effects of this violence. The old paradigm of reading such productions through the framework of regional allegiances—criollo and Andean—is monological and inadequate for interpreting novels and films composed in the postconflict period of the 1990s and 2000s. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2003 also altered significantly the predominant narrative of cultural trauma by shifting the focus from the Shining Path to government abuses. The first chapter of this dissertation studies precommission representations of the armed conflict in the criollo text Lituma en los Andes by Mario Vargas Llosa and the Andean text Rosa Cuchillo by Oscar Colchado. Despite supposed differences in ideology and representations of lo andino, both construct a space of death that communicates a pessimistic moral imagination because they cannot conceive of a nonviolent Peru. The second chapter shines a light on a shift in the cultural trauma discourse: detective fiction exposes the government as the main perpetrators of the internal conflict. -

Maria Guinand: Conductor, Teacher, and Promoter of Latin American Choral Music Angel M

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Maria Guinand: Conductor, Teacher, and Promoter of Latin American Choral Music Angel M. Va#squez-Ramos Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MARIA GUINAND: CONDUCTOR, TEACHER, AND PROMOTER OF LATIN AMERICAN CHORAL MUSIC By ANGEL M. VAZQUEZ-RAMOS A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2010 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Angel M. Vázquez-Ramos defended on August 4, 2010. _________________________________ André J. Thomas Professor Directing Dissertation _________________________________ Michelle Stebleton University Representative _________________________________ Judy K. Bowers Committee Member _________________________________ Kevin A. Fenton Committee Member Approved: ________________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicate this to my wife, Jody, for her unconditional love and support. And to my daughter Lucia Isabel. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my thanks to the members of my committee for their assistance throughout this process, and for all the lessons they have taught me directly and indirectly during the last twelve years. To Dr. André J. Thomas for sharing with me his skills, knowledge, passion and love for making music with others. To Dr. Kevin A. Fenton for his kindness and positive approach to teaching. To Dr. Judy K. Bowers for empowering me to be the skilled and passionate music educator I have always wanted to be. -

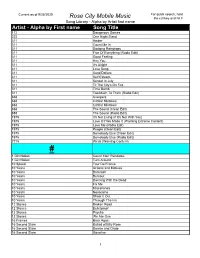

Rose City Mobile Music

Current as of 1/5/2018 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title ~ Black rows are new additions # 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 311 Til The City's On Fire 0:00 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Creepers 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 0:00 The Sound (Clean Edit) 0:00 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) (Hed) P.E. Closer (Clean Radio Edit) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years Novacaine 12 Stones Broken Road 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975.. Chocolate 1975.. Girls (Warning Content) 1Love f Corey Hart Truth Will Set U Free 2 Chainz Crack (Warning Content) 2 Chainz I'm Different (Warning Content) 2 Chainz Riot (Clean Edit) 2 Chainz Spend It (Warning Content) 2 Chainz Used 2 (Warning Content) 2 Chainz Watch Out (Clean Edit) (Warning Extreme Content) 2 Chainz f Cap 1 Where U Been (Clean Edit) (Warning Extreme Content) 2 Chainz f Drake No Lie (Clean Edit) (Warning Content) 2 Chainz f Drake Big Amount (Clean Edit) (Warning Content) 2 Chainz -

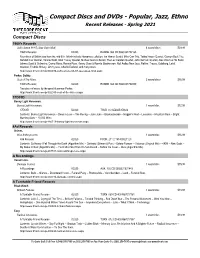

Compact Discs and Dvds - Popular, Jazz, Ethno Recent Releases - Spring 2021

Compact Discs and DVDs - Popular, Jazz, Ethno Recent Releases - Spring 2021 Compact Discs 1960's Records Soho Scene 66-67 (Jazz Goes Mod). 4 sound discs $29.98 1960's Records ©2020 RANDB 062 CD 5060331752165 Four discs of British jazz from the mid-60s. Artists include Humphrey Lyttelton, Ian Hamer Sextet, Mike Carr Trio, Tubby Hayes Quartet, Gordon Beck Trio, Rendell/Carr Quintet, Ronnie Scott, Stan Tracey Quartet, Michael Garrick Sextet, The Les Condon Quartet, John Surman Quartet, Alex Welsh & His Band, Johnny Scott & Orchestra, Danny Moss, Ronnie Ross, Kenny Clare & Ronnie Stephenson, Neil Ardley New Jazz, Rollins, Tracey, Goldberg, Laird, Seamen, Freddie McCoy, Jimmy Coe, Charlie Earland, and many more. http://www.tfront.com/p-502036-soho-scene-66-67-jazz-goes-mod.aspx Parker, Bobby. Soul of The Blues. 2 sound discs $16.98 1960's Records ©2020 RANDB 060 CD 5060331752059 Two discs of music by the great bluesman Parker. http://www.tfront.com/p-502035-soul-of-the-blues.aspx 37D03D Bonny Light Horseman. Bonny Light Horseman. 1 sound disc $12.98 37D03D ©2020 TSVD 8 2 656605350646 Contents: Bonny Light Horseman -- Deep in Love -- The Roving -- Jane Jane -- Blackwaterside -- Magpie's Nest -- Lowlands -- Mountain Rain -- Bright Morning Stars -- 10,000 Miles. http://www.tfront.com/p-486719-bonny-light-horseman.aspx 4Ad Records Grimes. Miss Anthropocene. 1 sound disc $16.98 4Ad Records ©2020 FOUR 211 2 191400021129 Contents: So Heavy I Fell Through the Earth (Algorithm Mix) -- Darkseid (Grimes & Pan) -- Delete Forever -- Violence (Original Mix) -- 4ÆM -- New Gods -- My Name Is Dark (Algorithm Mix) -- You'll Miss Me When I'm Not Around -- Before the Fever -- Idoru (Algorithm Mix). -

Best of Times Djs Client Songbook - Sorted by Song Title

Best of Times DJs Client Songbook - Sorted by Song Title Song Title Artist '49 Mercury Blues Setzer, Brian Orchestra, The #34 Matthews, Dave Band, The #Selfie Chainsmokers, The 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z f./ Beyoncé 1 Thing Amerie f./ Jay-Z 1, 2 Step Ciara f./ Missy Elliott 1,2,3,4 (I Love You) Plain White T's 1,2,3,4 (Sump in' New) Coolio 10 Million Miles Griffin, Patty 100 Years Five For Fighting 100% Pure Love Waters, Crystal 18 And Life Skid Row 1812 Overture Studio Band 19 You & Me Dan & Shay 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1984 Bowie, David 1984 Short Intro Van Halen 1985 Bowling For Soup 1994 Aldean, Jason 1999 Prince 2 On Tinashe f./ School Q 2001 Space Odyssey Williams, John 2012 (It Ain't The End) Sean, Jay f./ Nicki Minaj 20th Century Fox Studio Band 20th Century Fox Theme Morganstein, Bobby 21 Guns Green Day 21 Jump Street Theme 21 Jump Street 21 Summer Brothers Osborne 21st Century Girl Willow 22 Swift, Taylor 24K Magic Bruno Mars 34+35 Grande, Ariana 3AM Matchbox Twenty 3AM Eternal KLF, The 4 Minutes Madonna f./ Justin Timberlake & Timbaland 409 Beach Boys, The 5 o' Clock T-Pain f./ Lily Allen & Wiz Khalifa 5 O' Clock World Vogues, The 5-1-5-0 Bentley, Dierks 54-46 Was My Number Toots & The Maytals w/ Jeff Beck 6 Minuets, WoO 10: No. 2 In G Major (Beethoven) Preucil, William & Cary Lewis 6 N The Mornin' (Explicit) Ice-T 6,8,12 McKnight, Brian 634-5789 Adkins, Trace 634-5789 Pickett, Wilson 679 Fetty Wap f./ Remy Boyz 6am J Balvin f./ Farruko 7 Years Graham, Lukas 7 Years (Piano Version) Don't Stop Piano -

Alpha by First Name Song Title

Current as of 9/26/2020 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Amber 311 Count Me In 311 Dodging Raindrops 311 Five Of Everything (Radio Edit) 311 Good Feeling 311 Hey You 311 It's Alright 311 Love Song 311 Sand Dollars 311 Self Esteem 311 Sunset In July 311 Til The City's On Fire 311 Time Bomb 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 888 Creepers 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 The Sound (Clean Edit) 888 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 It's Not Living (If It's Not With You) 1975 Love It If We Made It (Warning Extreme Content) 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 1975 People (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) 7715 Week (Warning Content) # 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Burnout 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Novacaine 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 12 Stones Broken Road 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 1 Current as of 9/26/2020 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975.