The 39 Steps (1935)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 A.M

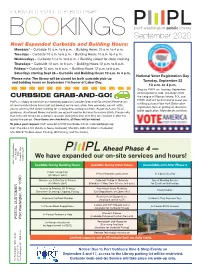

YOUR MONTHLY GUIDE TO PORT’S LIBRARY BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Wednesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building closed for deep cleaning. Thursdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Fridays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays starting Sept 26 – Curbside and Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. National Voter Registration Day *Please note: The library will be closed for both curbside pick-up and building hours on September 7 in honor of Labor Day. Tuesday, September 22 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Stop by PWPL on Tuesday, September 22 to register to vote. Volunteers from CURBSIDE GRAB-AND-GO! the League of Woman Voters, FOL and PWPL staff will be on hand to assist you PWPL is happy to continue our extremely popular Curbside Grab-and-Go service! Reserve any in filling out your New York State voter of your favorite library items (not just books!) online and, when they are ready, we will notify registration form or getting an absentee you to come by the library building for a contactless pickup out front. As per ALA and OCLC ballot application. More details to follow. guidance, all returned library materials are quarantined for 96 hours to ensure safety. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

![1940-08-29, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5100/1940-08-29-p-805100.webp)

1940-08-29, [P ]

SPECIAL LABOR EDITION THE NEWARK LEADER, THURSDAY, AUGUST 29, 1940 SPECIAL LABOR EDITION family visited Mr. and Mrs. Cary Newark Men Will McKinney Sunday. MIDLAND - AUDITORIUM SHOWS Miss Mary Klingenberg of Unemployment Bureau of Athens visited Mr. and Mrs. Enjoy Sailing Cary McKinney on Sunday after “SOUTH OF PAGO PAGO” noon. Now playing, Thursday to Mrs. Blanche Evans, son Rus Saturday, August 29-31, at the Schooner Trip sell, her daughter Mrs. Violet Great Importance to Workers Midland theatre — a thrilling Brunner, her grandson Llewellyn tropic love drama of the south Jerome Norpell, Wm. M. Ser Courson and Mrs. Nan Minego Of great importance to the days or more. Members of the seas with a stellar cast of play geant, George Pfeffer, John went on a picnic to Baughman’s Welfare of Licking county’s staff also made 1950 calls on ers, enacting a story of thrilling Spencer and Dr. Paul McClure, park Sunday. workers is District Office No. 38, prospective employers, explain adventure. “South of Pago will leave this Friday for Maine, Mrs. Blanche Evans visited Bureau of Unemployment Com ing the service and soliciting op Pago” starring Jon Hall, Fran on a short vacation trip. It is friends in Delaware and Marion pensation, located at 28-30 North enings. ces Farmer, Victor McLagen and their plan to sail on a Small last week. Fourth street. The nine mem One of the most successful em others concerns the strange ad schooner off the coast of Maine, Mr. and Mrs. Earl Gleckler bers of the staff consist of John ployment campaigns conducted ventures of Bucko Larson and and enjoy the fabulous fishing and daughter and Leroy Rowe of Gilbert, manager, and two sen in Newark during the period Ruby Taylor, who undertake an grounds and beautiful scenery Martinsburg road were Sunday ior and two junior interviewers; was the “Clean Up—Give a Job” adventure to the famous pearl along the coast. -

Notions of the Gothic in the Films of Alfred Hitchcock. CLARK, Dawn Karen

Notions of the Gothic in the films of Alfred Hitchcock. CLARK, Dawn Karen. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19471/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version CLARK, Dawn Karen. (2004). Notions of the Gothic in the films of Alfred Hitchcock. Masters, Sheffield Hallam University (United Kingdom).. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Sheffield Hallam University Learning and IT Services Adsetts Centre City Campus Sheffield S1 1WB Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10694352 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10694352 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Notions of the Gothic in the Films of Alfred Hitchcock Dawn Karen Clark A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Master of Philosophy July 2004 Abstract The films of Alfred Hitchcock were made within the confines of the commercial film industries in Britain and the USA and related to popular cultural traditions such as the thriller and the spy story. -

The Blackguard

THE BLACKGUARD GRAHAM CUTTS, GREAT BRITAIN/GERMANY, 1925 Screening: Sunday 22nd April, 9am Studios during and after the Second CAST World War – had encouraged Hitchcock to study the production methods of UFA, and, in an attempt to capitalise upon the Jane Novak ... European market, Balcon sent Cutts and Hitchcock to Berlin for the production of Prinzessin Maria The Blackguard. Cutts – the director re- Idourska / Princess Ma- sponsible for the BBFC-baiting Cocaine rie Idourska (1922) screened as part of Friday’s ‘What Walter Rilla ... The Silent Censor Saw’ presentation – had collaborated with Hitchcock on a Michael Caviol, The number of occasions. The Blackguard rep- Blackguard resents Hitchcock’s last role as art direc- Image courtesy of bfi Stills, Posters and tor, but he had previously work under Frank Stanmore ... Designs Graham Cutts in that role on four occa- Pompouard sions: Woman to Woman (1923), The White Shadow (1924), The Prude’s Fall (1924) and Bernhard Goetzke ... Graham Cutts’ 1925 film, The Black- The Passionate Adventure (1924). The Black- guard, precedes probably his most fa- guard, however, is the first instance of a Adrian Levinsky mous work, the Ivor Novello vehicle The Gainsborough film being shot abroad, and Rat, by one year, and is notable for Al- was budgeted at considerable expense for fred Hitchcock’s significant contribution the time. It was released in multilingual – he fulfilled the role of scenarist by versions, being retitled Die Prinzessin und adapting the original Raymond Paton der Geiger for the German market. novel for the silver screen, and also con- tributed his considerable talents to the Based on the 1917 Raymond Paton novel art direction of the film, while being re- of the same name, The Blackguard’s plot is sponsible for some second-unit photog- a melodrama set during the Russian Revo- raphy. -

Boredom Takestoll at Welles Village I Prixeweek Puzzle Today: Win $100

PAGE TWENTY <- EVENING HERALD, Fri., Sept. 7, 1979 Boredom TakesToll at Welles Village I Prixeweek Puzzle Today: Win $100 Hy DAVK I, VVAM,KK village. There are over 300 of them, starting point and perhaps funds for afraid the young'persons will find out vices Bureaus' programs because has found a way to do that yet,” Hoff Unique Music Book Board Approves Hiring Teachers Subpoenaed Chris Evert Stops King this project are next to impossible, Mfriilil Ki'iiorlcr but out of that group eight are giving and will come back to avenge the they do not think they would fit in man explained. Made for Silent Films Of New Science Head For Court Defiance To Reach Open Finals us problems. Two or three of them but there could be other areas such report,” Willett said. with programs. Hoffman said that one of the GLASTONBURY - On any hot, are supplying beer to kids who are as athletic equipment stocked at the Willett said that the major way to "We like rugged things,'- one solutions would be to separate the P age 2 P age 6 P age 6 Page 1 0 humid night in Welles Village, the underaged and I am going to do rental office for sign out use or a curb these problems would be to juvenile said. “We do different kinds scene js the same. Young persons elderly people in the village from the h---------- ---------- ' ■ everything in my power to throw the CETA worker to run various sports provide more recreationai oppor of things than the kinds of things they juveniles. -

Cataleg Definitiu.Pdf

Quan el 1934 Madeleine Carroll va trepitjar per primera vegada la Costa Brava, aquesta actriu anglesa era encara poc coneguda fora de les pantalles britàniques. L’imminent pas cap a Hollywood li va fer encetar una carrera fulgurant impulsada pel treball amb alguns dels més prestigiosos directors del moment: John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, William Dieterle, Cecil B. de Mille… Va ser en aquesta època quan les nostres comarques es van convertir en refugi de l’estrella entre rodatge i rodat- ge, però la tranquil·litat que més anhelava es va veure interrompuda per l’esclat de la Guerra Civil, que la va mantenir allunyada de la seva propietat catalana. En poc temps la mateixa ombra de la guerra s’estendria per tot Europa. Madeleine Carroll no va voler ser una simple espectadora del conflicte i va decidir-se a parti- cipar activament per recuperar la pau i els valors democràtics i es va implicar d’una manera molt personal com a membre de la Creu Roja, per donar suport a les vícti- mes més directes de la guerra, sobretot als nens orfes francesos i als soldats ame- ricans ferits. Ara, aprofitant el centenari del seu naixement i valent-nos d’alguns objectes i docu- ments del llegat de l’actriu, que ella mateixa conservava com els seus records més preuats, us proposem fer un recorregut per descobrir els diferents aspectes de la vida de Madeleine Carroll, des del més glamourós al més compromès. UNA ACTRIU ANGLESA A HOLLYWOOD Poc temps després de descobrir la passió pel teatre a la universitat, Madeleine Carroll (West Bromwich, Birmingham, 1906) que exercia de professora de francès, va viatjar a Londres a estudiar interpretació, obviant l’oposició familiar. -

John Buchan Wrote the Thirty-Nine Steps While He Was Ill in Bed with a Duodenal Ulcer, an Illness Which Remained with Him All His Life

John Buchan wrote The Thirty-Nine Steps while he was ill in bed with a duodenal ulcer, an illness which remained with him all his life. The novel was his first ‘shocker’, as he called it — a story combining personal and political dramas. The novel marked a turning point in Buchan's literary career and introduced his famous adventuring hero, Richard Hannay. He described a ‘shocker’ as an adventure where the events in the story are unlikely and the reader is only just able to believe that they really happened. The Thirty-Nine Steps is one of the earliest examples of the 'man-on-the-run' thriller archetype subsequently adopted by Hollywood as an often-used plot device. In The Thirty-Nine Steps, Buchan holds up Richard Hannay as an example to his readers of an ordinary man who puts his country’s interests before his own safety. The story was a great success with the men in the First World War trenches. One soldier wrote to Buchan, "The story is greatly appreciated in the midst of mud and rain and shells, and all that could make trench life depressing." Richard Hannay continued his adventures in four subsequent books. Two were set during the war when Hannay continued his undercover work against the Germans and their allies The Turks in Greenmantle and Mr Standfast. The other two stories, The Three Hostages and The Island of Sheep were set in the post war period when Hannay's opponents were criminal gangs. There have been several film versions of the book; all depart substantially from the text, for example, by introducing a love interest absent from the original novel. -

53 Life and Death of Mr. Badman Sabon.Rtf

THE LIFE AND DEATH OF MR. BADMAN, PRESENTED TO THE WORLD IN A FAMILIAR DIALOGUE BETWEEN MR. WISEMAN AND MR. ATTENTIVE. BY JOHN BUNYAN Printed by J. A. for Nath. Ponder, at the Peacock in the Poultry, near the Church, 1680. ADVERTISEMENT BY THE EDITOR. The life of Badman is a very interesting among the most degraded classes of society. description, a true and lively portraiture, of the Swearing was formerly considered to be a habit demoralized classes of the trading community of gentility; but now it betrays the blackguard, in the reign of King Charles II; a subject which even when disguised in genteel attire. Those naturally led the author to use expressions dangerous diseases which are so surely engend- familiar among such persons, but which are ered by filth and uncleanness, he calls not by now either obsolete or considered as vulgar. In Latin but by their plain English names. In every fact it is the only work proceeding from the case, the Editor has not ventured to make the prolific pen and fertile imagination of Bunyan, slightest alteration; but has reprinted the whole in which he uses terms that, in this delicate and in the author’s plain and powerful language. refined age, may give offence. So, in the The life of Badman forms a third part to the venerable translation of the holy oracles, there Pilgrim’s Progress, not a delightful pilgrimage are some objectionable expressions, which, to heaven, but, on the contrary, a wretched although formerly used in the politest company, downward journey to the infernal realms. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Timeline London's Hollywood: the Gainsborough

Timeline / London’s Hollywood: The Gainsborough Studio in the Silent Years 1 Timeline London’s Hollywood: The Gainsborough Studio in the Silent Years 1919 4/1919 Formation of Famous Players Lasky British Producers Limited 7/1919 Arrival of Albert A. Kaufman (production supervisor) Arrival of Richard Murphy (scenic artist) and others 8/1919 Arrival of Eve Unsell (head of scenario) 10/1919 Purchase of lease on building to be converted into studio 11/1919 Arrival of Milton Hoffman (general manager) 1920 2/1920 Appointment of Mde Langfier in Paris to run wardrobe department 3/1920 Arrival of Adolph Zukor 4/1920 Arrival of director Hugh Ford 5/1920 Opening of the studio 5/1920 Filming of The Great Day (May-June) 5/1920 Major Bell promoted to studio manager 6/1920 Arrival of Jesse Lasky 7/1920 Major Bell to America for three months 8/1920 Appointment of Robert James Cullen as assistant director 8/1920 Filming of The Call of Youth (August - September) 9/1920 Filming exteriors of The Call of Youth in Devon 9/1920 Eve Unsell returns to America 9/1920 Arrival of Margaret Turnbull, Roswell Dague (Scenarists) & Robert MacAlarney (General Production Manager) 10/1920 Arrival of Major Bell & director Donald Crisp 10/1920 Milton Hoffman returns to America 10/1920 Major Bell appoints James Sloan (Assistant Manager) 10/1920 Filming Appearances (October - December) 10/1920 Arrival of Paul Powell 11/1920 Trade Show The Great Day Trade Show The Call of Youth 12/1920 Filming The Mystery Road (December – May) Exteriors on the Riviera (December -February) Interiors