Surveys of Intertidal and Subtidal Biota of the Derwent Estuary – 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saltmarsh and Samphire

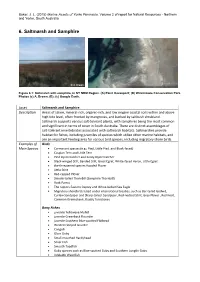

Baker, J. L. (2015) Marine Assets of Yorke Peninsula. Volume 2 of report for Natural Resources - Northern and Yorke, South Australia 6. Saltmarsh and Samphire © A. Brown Figure 6.1: Saltmarsh with samphire, in NY NRM Region. (A) Point Davenport; (B) Winninowie Conservation Park. Photos (c) A. Brown. (B): (c) Google Earth. Asset Saltmarsh and Samphire Description Areas of saline, mineral-rich, organic-rich, and low oxygen coastal soils within and above high tide level, often fronted by mangroves, and backed by saltbush shrubland. Saltmarsh supports various salt-tolerant plants, with samphires being the most common and significant in terms of cover in South Australia. There are distinct assemblages of salt-tolerant invertebrates associated with saltmarsh habitats. Saltmarshes provide habitat for fishes, including juveniles of species which utilise other marine habitats, and are an important feeding area for various bird species, including migratory shore birds. Examples of Birds Main Species Cormorant species (e.g.; Pied, Little Pied, and Black-faced) Caspian Tern and Little Tern Pied Oystercatcher and Sooty Oystercatcher Black-winged Stilt, Banded Stilt, Great Egret, White-faced Heron, Little Egret the threatened species Hooded Plover Little Stint Red-capped Plover Slender-billed Thornbill (Samphire Thornbill) Rock Parrot The raptors Eastern Osprey and White-bellied Sea Eagle Migratory shorebirds listed under international treaties, such as Bar-tailed Godwit, Curlew Sandpiper and Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, Red-necked Stint, Grey Plover , Red Knot, Common Greenshank, Ruddy Turnstones Bony Fishes juvenile Yelloweye Mullet juvenile Greenback Flounder juvenile Southern Blue-spotted Flathead Western Striped Grunter Congolli Glass Goby Small-mouthed Hardyhead Silver Fish Smooth Toadfish Goby species such as Blue-spotted Goby and Southern Longfin Goby Adelaide Weedfish Baker, J. -

New Zealand Fishes a Field Guide to Common Species Caught by Bottom, Midwater, and Surface Fishing Cover Photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola Lalandi), Malcolm Francis

New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing Cover photos: Top – Kingfish (Seriola lalandi), Malcolm Francis. Top left – Snapper (Chrysophrys auratus), Malcolm Francis. Centre – Catch of hoki (Macruronus novaezelandiae), Neil Bagley (NIWA). Bottom left – Jack mackerel (Trachurus sp.), Malcolm Francis. Bottom – Orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus), NIWA. New Zealand fishes A field guide to common species caught by bottom, midwater, and surface fishing New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No: 208 Prepared for Fisheries New Zealand by P. J. McMillan M. P. Francis G. D. James L. J. Paul P. Marriott E. J. Mackay B. A. Wood D. W. Stevens L. H. Griggs S. J. Baird C. D. Roberts‡ A. L. Stewart‡ C. D. Struthers‡ J. E. Robbins NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Wellington 6241 ‡ Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, 6011Wellington ISSN 1176-9440 (print) ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-1-98-859425-5 (print) ISBN 978-1-98-859426-2 (online) 2019 Disclaimer While every effort was made to ensure the information in this publication is accurate, Fisheries New Zealand does not accept any responsibility or liability for error of fact, omission, interpretation or opinion that may be present, nor for the consequences of any decisions based on this information. Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries website at http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-and-resources/publications/ A higher resolution (larger) PDF of this guide is also available by application to: [email protected] Citation: McMillan, P.J.; Francis, M.P.; James, G.D.; Paul, L.J.; Marriott, P.; Mackay, E.; Wood, B.A.; Stevens, D.W.; Griggs, L.H.; Baird, S.J.; Roberts, C.D.; Stewart, A.L.; Struthers, C.D.; Robbins, J.E. -

Four Marine Digenean Parasites of Austrolittorina Spp. (Gastropoda: Littorinidae) in New Zealand: Morphological and Molecular Data

Syst Parasitol (2014) 89:133–152 DOI 10.1007/s11230-014-9515-2 Four marine digenean parasites of Austrolittorina spp. (Gastropoda: Littorinidae) in New Zealand: morphological and molecular data Katie O’Dwyer • Isabel Blasco-Costa • Robert Poulin • Anna Falty´nkova´ Received: 1 July 2014 / Accepted: 4 August 2014 Ó Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014 Abstract Littorinid snails are one particular group obtained. Phylogenetic analyses were carried out at of gastropods identified as important intermediate the superfamily level and along with the morpholog- hosts for a wide range of digenean parasite species, at ical data were used to infer the generic affiliation of least throughout the Northern Hemisphere. However the species. nothing is known of trematode species infecting these snails in the Southern Hemisphere. This study is the first attempt at cataloguing the digenean parasites Introduction infecting littorinids in New Zealand. Examination of over 5,000 individuals of two species of the genus Digenean trematode parasites typically infect a Austrolittorina Rosewater, A. cincta Quoy & Gaim- gastropod as the first intermediate host in their ard and A. antipodum Philippi, from intertidal rocky complex life-cycles. They are common in the marine shores, revealed infections with four digenean species environment, particularly in the intertidal zone representative of a diverse range of families: Philo- (Mouritsen & Poulin, 2002). One abundant group of phthalmidae Looss, 1899, Notocotylidae Lu¨he, 1909, gastropods in the marine intertidal environment is the Renicolidae Dollfus, 1939 and Microphallidae Ward, littorinids (i.e. periwinkles), which are characteristic 1901. This paper provides detailed morphological organisms of the high intertidal or littoral zone and descriptions of the cercariae and intramolluscan have a global distribution (Davies & Williams, 1998). -

Márcia Alexandra the Course of TBT Pollution in Miranda Souto the World During the Last Decade

Márcia Alexandra The course of TBT pollution in Miranda Souto the world during the last decade Evolução da poluição por TBT no mundo durante a última década DECLARAÇÃO Declaro que este relatório é integralmente da minha autoria, estando devidamente referenciadas as fontes e obras consultadas, bem como identificadas de modo claro as citações dessas obras. Não contém, por isso, qualquer tipo de plágio quer de textos publicados, qualquer que seja o meio dessa publicação, incluindo meios eletrónicos, quer de trabalhos académicos. Márcia Alexandra The course of TBT pollution in Miranda Souto the world during the last decade Evolução da poluição por TBT no mundo durante a última década Dissertação apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Toxicologia e Ecotoxicologia, realizada sob orientação científica do Doutor Carlos Miguez Barroso, Professor Auxiliar do Departamento de Biologia da Universidade de Aveiro. O júri Presidente Professor Doutor Amadeu Mortágua Velho da Maia Soares Professor Catedrático do Departamento de Biologia da Universidade de Aveiro Arguente Doutora Ana Catarina Almeida Sousa Estagiária de Pós-Doutoramento da Universidade da Beira Interior Orientador Carlos Miguel Miguez Barroso Professor Auxiliar do Departamento de Biologia da Universidade de Aveiro Agradecimentos A Deus, pela força e persistência que me deu durante a realização desta tese. Ao apoio e a força dados pela minha família para a realização desta tese. Á Doutora Susana Galante-Oliveira, por toda a aprendizagem científica, paciência e pelo apoio que me deu nos momentos mais difíceis ao longo deste percurso. Ao Sr. Prof. Doutor Carlos Miguel Miguez Barroso pela sua orientação científica. -

Assessment of the Importance of Different Near-Shore Marine Habitats

Assessment of the importance of different near-shore marine habitats to important fishery species in Victoria using standardised survey methods, and in temperate and sub-tropical Australia using stable isotope analysis Jeremy Hindell, Gregory Jenkins, Rod Connolly and Glenn Hyndes Project No. 2001/036 Assessment of the importance of different near-shore marine habitats to important fishery species in Victoria using standardised survey methods, and in temperate and sub-tropical Australia using stable isotope analysis Jeremy S. Hindell1, Gregory P. Jenkins1, Rod M. Connolly2, Glenn A. Hyndes3 1 Marine and Freshwater Systems, Primary Industries Research Victoria, Department of Primary Industries, Queenscliff 3225 2 School of Environmental & Applied Sciences, Griffith University, Queensland 9726 3 School of Natural Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Western Australia 6027 October 2004 2001/036 © Fisheries Research and Development Corporation and Primary Industries Research Victoria. 2005 This work is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process, electronic or otherwise, without the specific written permission of the copyright owners. Neither may information be stored electronically in any form whatsoever without such permission. ISBN 1 74146 474 9 Preferred way to cite: Hindell JS, Jenkins GP, Connolly RM and Hyndes G (2004) Assessment of the importance of different near-shore marine habitats to important fishery species in Victoria using standardised survey methods, and in temperate and sub-tropical Australia using stable isotope analysis. Final report to Fisheries Research and Development Corporation Project No. 2001/036. Primary Industries Research Victoria, Queenscliff. Published by Primary Industries Research Victoria, Marine and Freshwater Systems, Department of Primary Industries, Queenscliff, Victoria, 3225. -

Biogenic Habitats on New Zealand's Continental Shelf. Part II

Biogenic habitats on New Zealand’s continental shelf. Part II: National field survey and analysis New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 202 E.G. Jones M.A. Morrison N. Davey S. Mills A. Pallentin S. George M. Kelly I. Tuck ISSN 1179-6480 (online) ISBN 978-1-77665-966-1 (online) September 2018 Requests for further copies should be directed to: Publications Logistics Officer Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 WELLINGTON 6140 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0800 00 83 33 Facsimile: 04-894 0300 This publication is also available on the Ministry for Primary Industries websites at: http://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-and-resources/publications http://fs.fish.govt.nz go to Document library/Research reports © Crown Copyright – Fisheries New Zealand TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 Overview 3 1.2 Objectives 4 2. METHODS 5 2.1 Selection of locations for sampling. 5 2.2 Field survey design and data collection approach 6 2.3 Onboard data collection 7 2.4 Selection of core areas for post-voyage processing. 8 Multibeam data processing 8 DTIS imagery analysis 10 Reference libraries 10 Still image analysis 10 Video analysis 11 Identification of biological samples 11 Sediment analysis 11 Grain-size analysis 11 Total organic matter 12 Calcium carbonate content 12 2.5 Data Analysis of Core Areas 12 Benthic community characterization of core areas 12 Relating benthic community data to environmental variables 13 Fish community analysis from DTIS video counts 14 2.6 Synopsis Section 15 3. RESULTS 17 3.1 -

GMB.CV-'07 Full General

CURRICULUM VITAE: GEORGE MEREDITH BRANCH 2.1. Biographic sketch: BORN : Salisbury, Zimbabwe, 25 September 1942. Married, two children. UNIVERSITY EDUCATION: University of Cape Town. B.Sc. 1963 Majors in Zoology and Botany, distinction in the former. Class medals for best student in second and third year Zoology. B.Sc. Hons. 1964. First class honours in Zoology PhD 1973. EMPLOYMENT: Zoology department, University of Cape Town Junior Lecturer, 1965-1966 Lecturer, 1967-1974 Ad hoc promotion to Senior Lecturer 1975 Ad hoc promotion to Associate Professor, 1979 Ad hom . promotion to Professorship 1985. Student adviser, Life Sciences, 1975-1987 Postgraduate Summer Course, Friday Harbor Marine Laboratories, 1985. Head of Department of Zoology, UCT, 1988-1990, 1994-1996 Chairman, School of Life Sciences, 1991 Chairman, Undergraduate Affairs, Zoology Department 1993 AWARDS: Purcell Prize for best postgraduate biological thesis - 1965. Fellowship of the University of Cape Town - 1983 Distinguished Teachers Award - 1984 UCT Book Award - 1986 - for "The Living Shores of Southern Africa". Fellowship of the Royal Society of South Africa - 1990. Appointed Director of FRD Coastal Ecology Unit -1991. Awarded Gold Medal by Zoological Society of Southern Africa - 1992. Awarded Gilchrist Gold Medal for contributions to marine science - 1994. UCT Book Award - 1995 - for "Two Oceans - a Field Guide to the Marine Life of southern Africa" (Jointly awarded to CL Griffiths, ML Branch, LE Beckley.) International Temperate Reefs Award for Lifetime Contributions to Marine Science – 2006. FRD RATING AND FUNDING: Rated in 1985 as qualifying for comprehensive support for funding from the Foundation for Research Development. Re-rated in 1990, 1994 and 1998 as category 'A' (scientists recognised as international leaders – approximately the top 4% of scientists in South Africa). -

Type of the Paper (Article

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 2 March 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201803.0022.v1 1 Article 2 Gastropod Shell Dissolution as a Tool for 3 Biomonitoring Marine Acidification, with Reference 4 to Coastal Geochemical Discharge 5 David J. Marshall1*, Azmi Aminuddin1, Nurshahida Atiqah Hj Mustapha1, Dennis Ting Teck 6 Wah1 and Liyanage Chandratilak De Silva2 7 8 1Faculty of Science, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Jalan Tungku Link, BE1410, Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei 9 Darussalam; 10 2Faculty of Integrated Technologies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Jalan Tungku Link, BE1410, Bandar Seri 11 Begawan, Brunei Darussalam; 12 [email protected] (DJM); [email protected] (AA); [email protected] (NAM); 13 [email protected] (DTT); [email protected] (LCD) 14 Abstract: Marine water pH is becoming progressively reduced in response to atmospheric CO2 15 elevation. Considering that marine environments support a vast global biodiversity and provide a 16 variety of ecosystem functions and services, monitoring of the coastal and intertidal water pH 17 assumes obvious significance. Because current monitoring approaches using meters and loggers 18 are typically limited in application in heterogeneous environments and are financially prohibitive, 19 we sought to evaluate an approach to acidification biomonitoring using living gastropod shells. We 20 investigated snail populations exposed naturally to corrosive water in Brunei (Borneo, South East 21 Asia). We show that surface erosion features of shells are generally more sensitive to acidic water 22 exposure than other attributes (shell mass) in a study of rocky-shore snail populations (Nerita 23 chamaeleon) exposed to greater or lesser coastal geochemical acidification (acid sulphate soil 24 seepage, ASS), by virtue of their spatial separation. -

Digenea: Lecithasteridae) Recently Found in Australian Marine Fishes

FOLIA PARASITOLOGICA 48: 109-114, 2001 Weketrema gen. n., a new genus for Weketrema hawaiiense (Yamaguti, 1970) comb. n. (Digenea: Lecithasteridae) recently found in Australian marine fishes Rodney A. Bray1 and Thomas H. Cribb2 1Department of Zoology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK; 2Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland 4072, Australia Key words: Digenea, Lecithasteridae, Weketrema, Scolopsis, Plectorhinchus, Cheilodactylus, Latridopsis, Great Barrier Reef, Tasmania Abstract. A new genus, Weketrema, is erected in the family Lecithasteridae for the species hitherto known as Lecithophyllum hawaiiense. Weketrema hawaiiense (Yamaguti, 1970) comb. n. is redescribed from Scolopsis bilineatus (Bloch) (Perciformes: Nemipteridae) from Lizard Island and Heron Island, Queensland, Plectorhinchus gibbosus (Lacepède) (Perciformes: Haemulidae) from Heron Island and Cheilodactylus nigripes Richardson (Perciformes: Cheilodactylidae) and Latridopsis forsteri (Castelnau) (Perciformes: Latridae) from Stanley, northern Tasmania. The new genus is distinguished from related members of the family Lecithasteridae by its complete lack of a sinus-sac. Although placed in the subfamily Lecithasterinae pro tem, its true subfamily position is not entirely clear. Comment is made on its unusual distribution, both in terms of zoogeography and hosts. As more lecithasterid species are examined and Weketrema gen. n. emphasis is placed on the structure of the terminal genitalia, more unusual features are uncovered. This Diagnosis. Lecithasteridae: Lecithasterinae. Body paper is a report of a known species, Lecithophyllum small, elongate oval. Tegument unarmed. Pre-oral lobe hawaiiense Yamaguti, 1970, re-examined using newly distinct. Oral sucker subglobular, subterminal. Ventral collected Australian material, Differential Interference sucker oval, pre-equatorial. Prepharynx absent. Pharynx Contrast (DIC) microscopy and serial sections. -

Determining the Diet of New Zealand King Shag Using DNA Metabarcoding

Determining the diet of New Zealand king shag using DNA metabarcoding New Zealand King Shag, (Leucocarbo carunculatus) on Blumine Island, Marlborough Sounds, New Zealand in 2016 (Wikipedia commons). Aimee van der Reis & Andrew Jeffs Report Prepared For: Department of Conservation, Conservation Services Programme, Project BCBC2019-05. DOC MarineDRAFT Science Advisors Graeme Taylor and Dr Karen Middlemiss. November 2020 Reports from Auckland UniServices Limited should only be used for the purposes for which they were commissioned. If it is proposed to use a report prepared by Auckland UniServices Limited for a different purpose or in a different context from that intended at the time of commissioning the work, then UniServices should be consulted to verify whether the report is being correctly interpreted. In particular it is requested that, where quoted, conclusions given in Auckland UniServices reports should be stated in full. INTRODUCTION The New Zealand king shag (Leucocarbo carunculatus) is an endemic seabird that is classed as nationally endangered (Miskelly et al., 2008). The population is confined to a small number of colonies located around the coastal margins of the outer Marlborough Sounds (South Island, New Zealand); with surveys suggesting the population is currently stable (~800 individuals surveyed in 2020; Aquaculture New Zealand, 2020; Schuckard et al., 2015). Monitoring the colonies has become a priority and research is being conducted to better understand their population dynamics and basic ecology to improve the management of the population, particularly in relation to human activities such as fishing, aquaculture and land use (Fisher & Boren, 2012). The diet of the New Zealand king shag is strongly linked to the waters surrounding their colonies and it has been suggested that anthropogenic activities, such as marine farm structures, may displace foraging habitat that could affect the population of New Zealand king shag (Fisher & Boren, 2012). -

Reef Fishes of Conservation Concern in South Australia

Reef Fishes of Conservation Concern in South Australia A Field Guide In the end, we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught. — Baba Dioum, 1968. by Janine L. Baker, Marine Ecologist SUPPORTED BY THE Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board Acknowledgments Thanks to the Adelaide and Mt Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management (AMLR NRM) Board for supporting the development of this field guide. Particular thanks to Janet Pedler and Liz Millington at AMLR NRM Board for guidance, advice and support. I am grateful to DENR, especially Patricia von Baumgarten and Simon Bryars, for part- supporting my time in writing an e-book on South Australian fishes, from which much of the information in this field guide was derived. Thanks to all of the marine researchers and divers who generously provided images for this guide. In alphabetical order, they include: James Brook, Adrian Brown, Simon Bryars, Helen Crawford, Graham Edgar, Chris Hall, Barry Hutchins, Rudie Kuiter, Paul Macdonald, Phil Mercurio, David Muirhead, Kevin Smith and Rick Stuart-Smith. The keen eye and skill of these photographers have significantly contributed to the visual appeal and educational value of the work. A photograph from the internet has also been included, and thanks to the photographer Richard Ling for making his image of Girella tricuspidata available in the public domain. I am grateful to Graham Edgar, Scoresby Shepherd and Simon Bryars for taking the time to edit and proofread the draft text. Thanks to Céline Lawrence for formatting the draft booklet for web-based printing and hard copy printing. -

Molecular Genetics of Cirrhitoid Fishes (Perciformes: Cirrhitoidea

Molecular genetics of c·irrhitoid fishes (Perciformes: Cirrhitoidea): phylogeny, taxonomy, biogeography, and stock structure Christopher Paul Burridge BSc(Hons) University of Tasmania Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Tasmania October 2000 S1a~tements I declare that this thesis contains no material whicb has been accepted for the award of any otiler degree or diploma in any tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text. This thesis is to be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. October 2000 Summary The molecular phylogenetic relationships within three of the five cirrhitoid fish families were reconstructed from mitochondrial DNA cytochrome b, cytochrome oxidase I, and D-loop sequences. Analysis of the Cheilodactylidae provided evidence that much taxonomic revision is required. The molecular data suggest that this family should be restricted to the two South African Cheilodactylus, as they are highly divergent from the other cheilodactylids and one member is the type species. The remaining 25 cheilodactylids should be transferred to the Latridae. Nine of the non South African Cheilodactylus can be allocated to three new genera; Goniistius (elevated to generic rank), Zeodrius (resurrected), and Morwong (resurrected), while the placement of three species is uncertain. The three South African Chirodactylus should revert to Palunolepis, as they are distinct from the South American type species Chirodact_vlus variegatus. Acantholatris clusters within Nemadactylus, ar;d the former should be synonymised.