Herbarium Explorations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1958-18--The-Horticultural-Herbarium.Pdf

ARNOLDIA A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME 18 JUNE 27, IJSH NUMBER 5 THE HORTICULTURAL HERBARIUM* commercial growers, as well as to the laymen who buy their plants, cor- TO-t- rect scientific names are most important. The nurseryman must be certain of his product to maintain both his integrity and his business while the layman, with less at stake, may be motivated by a desire to have complete and correctly identified collections. Daily, the larger botanical and horticultural institutions are called upon to name cultivated plants. A few years ago when, for the most part, only well- known species or varieties were involved, this was hardly a problem. Today, how- ever, when hybrids and cultivars are in vogue, plant identification has become a difficult, time-consuming and unfortunately often a hopeless chore. It may be impossible to give a true name to the specimen of a hybrid or cultivar unless one has ample and complete material of the plant and sufficient additional material available for comparison. The Arnold Arboretum now has a separate horticultural herbarium of approx- imately 100,000 mounted specimens. This herbarium is composed of specimens gathered from its own extensive living collections, as well as of material culti- vated in other botanical or private gardens throughout the world. It is one of the largest of its kmd. The material for this herbarium has been accumulated over a period of time extending into the last century. Even so, many modern introductions, hybrids and cultivars, are lacking among the vouchers of our her- barium, as is no doubt the case with many another such institution. -

Catalogue of the Type Specimens in the National Herbarium of Cultivated Plants

e-book ISBN: 978-81-952644-1-4 Catalogue of the Type Specimens in the National Herbarium of Cultivated Plants Anjula Pandey RK Pamarthi K Pradheep Rita Gupta SP Ahlawat Division of Plant Exploration and Germplasm Collection ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources Pusa Campus, New Delhi - 110 012, India © 2021 ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources, New Delhi 110012, India This document is an outcome of taxonomic studies undertaken and new taxa described by the scientists of ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (ICAR-NBPGR), New Delhi. All technical descriptions and contents on ‘type’ discussed in this publication are provided with minor modifications in the original description. Images of ‘type’ specimen have been captured and documented by the NHCP. Citation: Pandey Anjula, RK Pamarthi, K Pradheep, Rita Gupta and SP Ahlawat (2021) Catalogue of the Type Specimens in the National Herbarium of Cultivated Plants. ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources, New Delhi, India, 67p + i-iii Technical support: Shashi Kant Sharma Cover page photo identity: Curcuma amada var. glabra (‘type’ specimen from Kerala) Published by: The Director ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources New Delhi 110012, India Contact Dr. Kuldeep Singh Director ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources, Pusa, New Delhi 110012, India E-mail: [email protected] e-book ISBN: 978-81-952644-1-4 Catalogue of the Type Specimens in the National Herbarium of Cultivated Plants Anjula Pandey RK Pamarthi K Pradheep Rita Gupta SP Ahlawat Division of Plant Exploration and Germplasm Collection ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources Pusa Campus, New Delhi - 110 012, India About the book………. -

A Primer on Herbarium-Based Phenological Research

Funding for the development of these materials was provided by the US Geological Survey and the USA National Phenology Network More phenology education materials and activities are available online, including a step-by-step guide to downloading and analyzing a real herbarium-based phenological data set using Microsoft Excel. Other available materials include annotated lectures for universities and the public; guides to establishing and using phenology gardens; seminar modules for undergraduate/graduate students; and standards- aligned K-12 lesson plans. To learn more and to download materials, visit the Education section of the California Phenology Project website (www.usanpn.org/cpp/education) or the USA National Phenology Network (www.usanpn.org/education). 2 Our understanding of the global climate system has advanced remarkably in recent decades, along with our awareness that changes in the climate system have affected plant and animal activities and geographic distributions. Biologists have been able to detect some of the impacts of climate change on both wild and cultivated species by exploring data sets from long-term monitoring efforts. Repeated annual surveys of events such as wildflower blooms, animal migrations, insect emergence, and crop harvests – which have been monitored for many reasons – have informed our understanding of the biological effects of climate change. In a landmark 2007 report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)1 summarized 28,671 long-term data series from around the world documenting significant -

The First Attempt to List the Archaeophytes of Iceland

Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae DOI: 10.5586/asbp.3608 ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Publication history Received: 2018-08-09 Accepted: 2018-12-05 The frst attempt to list the archaeophytes Published: 2018-12-31 of Iceland Handling editor Michał Ronikier, W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland Paweł Wąsowicz* Icelandic Institue of Natural History, Akureyri Division, Borgir við Norðurslóð, Pósthólf 180, 602 Funding Akureyri, Iceland This research was funded by the Icelandic Institute of Natural * Email: [email protected] History. Competing interests No competing interests have Abstract been declared. Tis article presents for the frst time a list of the possible archaeophytes from Iceland. In the present study, all the fowering plant taxa that are considered native/long Copyright notice © The Author(s) 2018. This is an established in Iceland were assessed against criteria designed to recognize possible Open Access article distributed archaeophytes. Te assessment resulted in a list of 39 taxa meeting (or possibly under the terms of the meeting) at least one research criterion. Nineteen taxa were classifed as possible Creative Commons Attribution archaeophytes, 10 were classifed as non-natives of unknown age (due to the inability License, which permits redistribution, commercial and to classify them as neither archaeophytes nor neophytes using the available data), noncommercial, provided that while the remaining 10 species were classifed as uncertain (doubtfully native). Te the article is properly cited. limitations of the present study in terms of both the methodology and the uncertain- ties connected with the classifcation of individual taxa are discussed. Citation Wąsowicz P. The frst attempt to list the archaeophytes of Keywords Iceland. -

History and Modern Uses of a Herbarium

History and Modern Uses of a Herbarium The History of Herbaria The term herbarium was first used as a collection of dried medicinal plants cataloged within a bound book3. In the 16th century, Luca Ghini (1490?-1556) is credited to be the first person to press and preserve plants under pressure, then bind the specimens within a book3. He was a Botany Professor at the University of Bologna, Italy. This practice quickly became the usual practice throughout Europe. Specimens were housed in researchers’ personal collections, and extra specimens were traded with other Portrait of Italian Botanist Luca Ghini5 (left) and a book containing 6 botanists3. pressed plant specimens (right) In the 18th century, Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), known as the “Father of Taxonomy” was faced with a challenge while preserving plants according to this Italian practice. As his collections expanded, it was difficult to catalog when binding the specimens within a book. He came up with a system that mounted one specimen per large sheet of paper7. After that, it would be cataloged with other closely-related plants and stored in cabinets, which provided room to add new material and allowed the shelves to function as a file cabinet. He decided the sheets of paper should be one size, that way when traded with other botanists, the collection remained uniform7. These Portrait of Carl Linnaeus1 (left), a photograph of his custom built cabinets (center), standards are still used today, several hundred years later. and a specimen of Delphinium grandiflorum from his personal collection4 (right) Not only do the standards remain, but so do the specimens. -

Reference Collections in Herbaria: a Versatile but Underutilized Tool to Enhance Teaching, Outreach and Research

Reference Collections in herbaria: A versatile but underutilized tool to enhance teaching, outreach and research. Neil Snow Director, T.M. Sperry Herbarium Department of Biology Pittsburg State University Pittsburg, KS 66762 nsnow [at sign] pittstate.edu Eugenia plurinervia (New Caledonia) Acknowledgements Andrea Weeks (George Mason University) Rob Naczi (New York Botanical Garden) Ron Hartman (Rocky Mountain Herbarium, University of Wyoming) Samantha Young (Pittsburg State University) Don Hazlett (New World Plants; Pierce, Colorado) Mit McGlaughlin (University of Northern Colorado) Ken Systma (University of Wisconsin-Madison) George Yatskievych (University of Texas-Austin) Species-rich temperate genera Astragalus – loco weeds (Fabaceae) Carex – sedges (Cyperaceae) Astragalus alpinus Crataegus – hawthorns (Rosaceae) Poa – blue grasses (Poaceae) Quercus – oaks (Fagaceae) Rubus – blackberries & allies (Rosaceae) Salix – willows (Salicaceae) Solidago altisissima ssp. altisissima Solidago –goldenrods (Asteraceae) “Difficult” temperate genera Astragalus – loco weeds (Fabaceae) Carex – sedges (Cyperaceae in general) Crataegus – hawthorns (Rosaceae) Poa – blue grasses (Poaceae in general) Quercus – oaks (Fagaceae) Rubus – blackberry and allies (Rosaceae) Salix – willows (Salicaceae) Solidago – goldenrods (Asteraceae in general) These genera species-rich across much or most of North America (and elsewhere) Floras alone sometimes inadequate to verify identifications Positive identification of specimens often requires comparison to a verified herbarium -

Plant Nomenclature and Taxonomy an Horticultural and Agronomic Perspective

3913 P-01 7/22/02 4:25 PM Page 1 1 Plant Nomenclature and Taxonomy An Horticultural and Agronomic Perspective David M. Spooner* Ronald G. van den Berg U.S. Department of Agriculture Biosystematics Group Agricultural Research Service Department of Plant Sciences Vegetable Crops Research Unit Wageningen University Department of Horticulture PO Box 8010 University of Wisconsin 6700 ED Wageningen 1575 Linden Drive The Netherlands Madison Wisconsin 53706-1590 Willem A. Brandenburg Plant Research International Wilbert L. A. Hetterscheid PO Box 16 VKC/NDS 6700 AA, Wageningen Linnaeuslaan 2a The Netherlands 1431 JV Aalsmeer The Netherlands I. INTRODUCTION A. Taxonomy and Systematics B. Wild and Cultivated Plants II. SPECIES CONCEPTS IN WILD PLANTS A. Morphological Species Concepts B. Interbreeding Species Concepts C. Ecological Species Concepts D. Cladistic Species Concepts E. Eclectic Species Concepts F. Nominalistic Species Concepts *The authors thank Paul Berry, Philip Cantino, Vicki Funk, Charles Heiser, Jules Janick, Thomas Lammers, and Jeffrey Strachan for review of parts or all of our paper. Horticultural Reviews, Volume 28, Edited by Jules Janick ISBN 0-471-21542-2 © 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1 3913 P-01 7/22/02 4:25 PM Page 2 2 D. SPOONER, W. HETTERSCHEID, R. VAN DEN BERG, AND W. BRANDENBURG III. CLASSIFICATION PHILOSOPHIES IN WILD AND CULTIVATED PLANTS A. Wild Plants B. Cultivated Plants IV. BRIEF HISTORY OF NOMENCLATURE AND CODES V. FUNDAMENTAL DIFFERENCES IN THE CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE OF CULTIVATED AND WILD PLANTS A. Ambiguity of the Term Variety B. Culton Versus Taxon C. Open Versus Closed Classifications VI. A COMPARISON OF THE ICBN AND ICNCP A. -

Fern Gazette

FERN GAZ. 17(6,7,8): 283-295. 2006 351 A MOULDING METHOD TO PRESERVE TREE FERN TRUNK SURFACES INCLUDING REMARKS ON THE COMPOSITION OF TREE FERN HERBARIUM SPECIMENS T. Janssen1, 2 1 Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Dépt. Systématique et Evolution, UMR-CNRS 5202 / USM 602, CP39, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05, France 2 Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, A.-v.-Haller-Institut für Pflanzenwissenschaften, Abt. Spezielle Botanik, Untere Karspüle 2, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; (e-mail: [email protected]) Key words: collection, Cyatheaceae, Dicksoniaceae, field annotation, herbarium specimen, imprinting, large ferns, moulding, silicone, trunk surface. ABSTRACT Ferns with a tree habit are mainly found in the families Cyatheaceae and Dicksoniaceae. Together, they constitute a diverse pantropical group of common to locally dominant elements of tropical floras, especially in montane forests. Many species have very restricted distribution ranges and some are highly threatened. Taxonomic understanding of these ferns, a prerequisite to successful establishment of conservation strategies, is hampered by the disparate and often insufficient quality of available herbarium material. During recent fieldwork, a time-efficient scheme has been developed permitting to maximize the information content of tree fern collections. A simple non-destructive silicone moulding method to preserve important characters of the trunk surface is introduced. A standardized annotation sheet as a field book supplement is provided along with a summary sheet of the presented collecting approach for quick reference in the field. Standardized annotations and associated collections such as stem moulds greatly augment the value of the specimen. INTRODUCTION Tree ferns constitute a significant fraction of plant diversity in the world’s (sub-) tropical forests with approximately 650 described species (Large & Braggins, 2004; Kubitzki, 1990). -

Phenological Research Using Herbarium Specimens

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works Title Old Plants, New Tricks: Phenological Research Using Herbarium Specimens. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3j22c19z Journal Trends in ecology & evolution, 32(7) ISSN 0169-5347 Authors Willis, Charles G Ellwood, Elizabeth R Primack, Richard B et al. Publication Date 2017-07-01 DOI 10.1016/j.tree.2017.03.015 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California TREE 2248 No. of Pages 16 Review Old Plants, New Tricks: Phenological Research Using Herbarium Specimens Charles G. Willis,1,* Elizabeth R. Ellwood,2,* Richard B. Primack,3 Charles C. Davis,1 Katelin D. Pearson,2 Amanda S. Gallinat,3 Jenn M. Yost,4 Gil Nelson,2 Susan J. Mazer,5 Natalie L. Rossington,5 Tim H. Sparks,6,7 and Pamela S. Soltis8 The timing of phenological events, such as leaf-out and flowering, strongly Trends influence plant success and their study is vital to understanding how plants will Phenology (i.e., the timing of flowering, respond to climate change. Phenological research, however, is often limited by leaf-out, and other recurring biological the temporal, geographic, or phylogenetic scope of available data. Hundreds of events) is an essential component in millions of plant specimens in herbaria worldwide offer a potential solution to measuring how species have responded and will continue to this problem, especially as digitization efforts drastically improve access to respond to climate change. collections. Herbarium specimens represent snapshots of phenological events Herbarium specimens are increasingly and have been reliably used to characterize phenological responses to climate. -

Collecting and Preparing Plant Specimens and Producing an Herbarium

Chapter 16 Collecting and Preparing Plant Specimens and Producing an Herbarium Loran C. Anderson Department of Biological Science Florida State University Tallahassee, Florida 32306-4370 (850) 644-6278; e-mail: [email protected] Loran C. Anderson received his B.S. and M.S. from Utah State University in 1958 and 1959 and a Ph.D. in botany from Claremont Graduate University in California in 1962. After teaching at Michigan State University and Kansas State University, he joined the Department of Biological Science at Florida State University in 1974. Professor Anderson serves as Curator of the Herbarium. His primary research interests are the anatomy and taxonomy of selected genera of plants, especially in the Asteraceae, and the study of rare and endangered species in Florida. Reprinted From: Anderson, L. C. 1999. Collecting and preparing plant specimens and producing an herbarium. Pages 295-300, in Tested studies for laboratory teaching, Volume 20 (S. J. Karcher, Editor). Proceedings of the 20th Workshop/Conference of the Association for Biology Laboratory Education (ABLE), 399 pages. - Copyright policy: http://www.zoo.utoronto.ca/able/volumes/copyright.htm Although the laboratory exercises in ABLE proceedings volumes have been tested and due consideration has been given to safety, individuals performing these exercises must assume all responsibility for risk. The Association for Biology Laboratory Education (ABLE) disclaims any liability with regards to safety in connection with the use of the exercises in its proceedings volumes. -

The Dudley Herbarium Including a Case Study of Terman’S Restructuring of the Biology Department

The Dudley Herbarium Including a case study of Terman’s restructuring of the biology department BY SARA TIMBY he history of the Dudley Herbarium embodies an intellectual tradition that spans a hundred years of fieldwork and publishing. The herbarium’s curators trained several generations of researchers, educators, and public and private land-use managers and fought hard to protect our forests, rangelands, and wetlands. It is exciting history, full of tales of exploration, political fights, and personal conflicts. The herbarium’s fate at TStanford is also a fascinating story, illuminating aspects of university decision-making and changes in the discipline of the biological sciences. Provost Frederick E. Terman’s decision in the early better combined research facility than ei- ther institution could maintain alone, and 1960s to terminate support for the Division of Systematic the hope of increased intellectual contact Biology is still a sore point for some faculty in the Depart- between members of Stanford’s biology department and the California Academy ment of Biological Sciences. The major result of the fund- of Sciences. Furthermore, the hope was ing loss was the eventual transfer, by long-term loan, of expressed that students would benefit from contact with Academy scientists and the two most important of Stanford’s rich Natural History from contact with scientists from the Uni- Museum collections to the California Academy of Sciences versity of California.1 But Provost Miller didn’t touch on the real reason behind the in San Francisco. These were the plant and fish collections, transfer, that the university administration both dating back to the beginning of the university. -

Module Herbarium Specimens

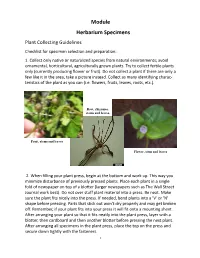

Module Herbarium Specimens Plant Collecting Guidelines Checklist for specimen selection and preparation: 1. Collect only native or naturalized species from natural environments; avoid ornamental, horticultural, agriculturally grown plants. Try to collect fertile plants only (currently producing flower or fruit). Do not collect a plant if there are only a few like it in the area, take a picture instead. Collect as many identifying charac- teristics of the plant as you can (i.e. flowers, fruits, leaves, roots, etc.). Root, rhizomes, stems and leaves, Fruit, stems and leaves Flower, stem and leaves 2. When filling your plant press, begin at the bottom and work up. This way you minimize disturbance of previously pressed plants. Place each plant in a single fold of newspaper on top of a blotter (larger newspapers such as The Wall Street Journal work best). Do not over stuff plant material into a press. Be neat. Make sure the plant fits nicely into the press. If needed, bend plants into a 'V' or 'N' shape before pressing. Parts that stick out won't dry properly and may get broken off. Remember, if your plant fits into your press it will fit onto a mounting sheet. After arranging your plant so that it fits neatly into the plant press, layer with a blotter, then cardboard and then another blotter before pressing the next plant. After arranging all specimens in the plant press, place the top on the press and secure down tightly with the fasteners. 1 You can make your own plant press. 12 inches X 18 inches. Two sturdy outer boards or you can build a frame such as the one pictured here, two or more pieces of cardboard cut to size , newspa- per, blotter or drying paper and straps or clamps to compress the layers firmly and You can also buy a plant press starting evenly together.