Domin, George OH115

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edition 2017

YEAR-END EDITION 2017 HHHHH # OVERALL LABEL TOP 40 LABEL RHYTHM LABEL REPUBLIC RECORDS HHHHH 2017 2016 2015 2014 GLOBAL HEADQUARTERS REPUBLIC RECORDS 1755 BROADWAY, NEW YORK CITY 10019 REPUBLIC #1 FOR 4TH STRAIGHT YEAR Atlantic (#7 to #2), Interscope (#5 to #3), Capitol Doubles Share Republic continues its #1 run as the overall label leader in Mediabase chart share for a fourth consecutive year. The 2017 chart year is based on the time period from November 13, 2016 through November 11, 2017. In a very unique year, superstar artists began to collaborate with each other thus sharing chart spins and label share for individual songs. As a result, it brought some of 2017’s most notable hits including: • “Stay” by Zedd & Alessia Cara (Def Jam-Interscope) • “It Ain’t Me” by Kygo x Selena Gomez (Ultra/RCA-Interscope) • “Unforgettable” by French Montana f/Swae Lee (Eardrum/BB/Interscope-Epic) • “I Don’t Wanna Live Forever” by ZAYN & Taylor Swift (UStudios/BMR/RCA-Republic) • “Bad Things” by MGK x Camila Cabello (Bad Boy/Epic-Interscope) • “Let Me Love You” by DJ Snake f/Justin Bieber (Def Jam-Interscope) • “I’m The One” by DJ Khaled f/Justin Bieber, Quavo, Chance The Rapper & Lil Wayne (WTB/Def Jam-Epic) All of these songs were major hits and many crossed multiple formats in 2017. Of the 10 Mediabase formats that comprise overall rankings, Republic garnered the #1 spot at two formats: Top 40 and Rhythmic, was #2 at Hot AC, and #4 at AC. Republic had a total overall chart share of 15.6%, a 23.0% Top 40 chart share, and an 18.3% Rhythmic chart share. -

Top 50 Music Charts March 30, 2017 Page 1

Top 50 Music Charts March 30, 2017 Page 1 By www.DJNTVInsider.com Pop 34 MAJOR LAZER Run Up f/PARTYNEXTDOOR/Minaj 17 2 CHAINZ X GUCCI MANE X QUAVO Good Drank 1 ED SHEERAN Shape Of You 35 STARGATE Waterfall f/P!nk & Sia 18 RAE SREMMURD Swang 2 ZAYN/TAYLOR SWIFT I Don’t Wanna Live Forever 36 AXWELL & INGROSSO I Love You f/Kid Ink 19 RICK ROSS I Think She Like Me f/Ty Dolla 3 THE WEEKND I Feel It Coming f/Daft Punk 37 MACHINE GUN KELLY At My Best f/Hailee Steinfeld 20 LECRAE Blessings f/Ty Dolla $ign 4 BRUNO MARS That’s What I Like 38 ZAYN Still Got Time f/PARTYNEXTDOOR 21 YFN LUCCI Everyday We Lit f/PnB Rock 5 THE CHAINSMOKERS Paris 39 SNAKEHIPS & MO Don’t Leave 22 NICKI MINAJ No Frauds w/Drake & Lil Wayne 6 RIHANNA Love On The Brain 40 DJ KHALED Shining f/Beyonce & Jay Z 23 FUTURE Mask Off 7 SHAWN MENDES Mercy 41 FUTURE Selfish f/Rihanna 24 FUTURE Draco 8 CLEAN BANDIT & ANNE-MARIE Rockabye f/Sean Paul 42 MIGOS Bad And Boujee f/Lil Uzi Vert 25 JEREMIH I Think Of You f/Chris Brown 9 KATY PERRY Chained To The Rhythm 43 LITTLE MIX Touch 26 BIBI BOURELLY Ballin 10 MARIAN HILL Down 44 CHANCE THE RAPPER All Night f/Knox Fortune 27 CHILDISH GAMBINO Redbone 11 KYGO X SELENA GOMEZ It Ain’t Me 45 AARON CARTER Sooner Or Later 28 TEE GRIZZLEY First Day Out 12 MAROON 5 Cold f/Future 46 ED SHEERAN Castle On The Hill 29 SWIFT Pull Up 13 THE CHAINSMOKERS & COLDPLAY Something Just Like This 47 G-EAZY & KEHLANI Good Life 30 B.O.B 4 Lit f/T.I. -

Good Drank (Feat. Gucci Mane & Quavo)

Good Drank (feat. Gucci Mane & Quavo) 2 Chainz Yeah, used to treat my mattress like the ATM yeah Bond number 9 that's my favorite scent, yeah Can't forget the kush I'm talking OG, oh yeah Rest in peace to pop, he was an OG Oh yeah, 285 I had that pack on me Uh, I can not forget I had that strap on me Yeah, rest in peace to my nigga Doe All he ever want to do is ball That was the easy part We playing that Weezy hard We sit in the kitchen late We tryna to make an escape Trying to make me a mil So I'mma keep me a plate I told 'em shawty can leave So I'mma keep me a rake So I'mma keep me a Wraith My jewelry look like a lake Today I'm in the Maybach And that car came with some drapes You know I look like a safe I put you back in your place I look you right in your face Sing to your bitch like I'm Drake, yeah Good drank, big knots Good drugs, I put a four on the rocks Drop top, no hot box 12 tried to pull me over, pink slips to the cops She said the molly give her thizz face Put the dick in her rib cage Whips out Kunta Kinte Diamonds clear like Bombay Take your babies, no Harambe Play with keys like Doc Dre 3K like André Need a girl call her, come through Your trunk in the front, well check this out my top in the trunk You play with my money then check this out your pop in the trunk Three mil in a month, but I just did three years on a bunk Oh you in a slump I'm headed to Oakland like Kevin Durant What is your point, square with the stamp, for Kevin Durant Lay on on my trap, play with my cap and I'll knock off your hat I'm taking the cheese -

'T ITUR S (11111) Ir

f NW" REMEMBERING CHUCK BERRY Little Richard on their friendship Buddy Guy on his mystery Robert Christgau on his genius Elvis Mitchell on race and rage • giez- 'T ITUR Hip-hop'sand far-out most —influential star made — S(11111) April 1-7,2017 I billboard.com history this month by scoring back-to-back No.1 albums. How to top that? 'If I'm the = biggest artist in the world, Ir cool, but I want to just be me' WorldRadioHistory We gotta make achange... It's time for us as apeople to start makin' some changes. Let's change the way we eat, let's change the way we live and let's change the way we treat each other. You see the old way wasn't working so it's on us to do what we gotta do, to survive. -TUPAC SHAKUR YOUR MESSAGE CONTINUES TO EDUCATE, INSPIRE AND CHANGE THE WORLD. CONGRATULATIONS TO TUPAC SHAKUR, HIS FAMILY AND ESTATE ON HIS INDUCTION INTO THE ROCK AND ROLL HALL OF FAME. ti WorldRadioHistory WorldRadioHistory • • •• .• ••• •.‘./t r. .• • • re , . • ed.. 1:•• THE RECORDING ACADEMY' • 44 • .... P. b • ▪ . • •. • • • • •• • ' • • • .......' . ...•. •. 4•••, L.4 , • 'e :Ss í • ' •I> 0> g e • ! 13 ••#t, ii• .1 e:;vi.e..i .".- *• , •.. ). `f*: ievÉtei# .0 .'e • ;$ 4.>,‘ ...e ets', .4;.• ,..... • 4.' 4 1, •bee : ee. • '. 0 , se tp• oft• 'é .. estP • . • 1. i :" I \ * . NI ettA* aet• t i 11 • I., el-eh , •1 .tt ?r 1 / ,f1 0 f. •, f.L.7- .e ! , ,.%. 1..111L ib 4 e ‘ .. • » s% i I ' 1 I I Ili; ..! . •- 4 III ( ' t ' . -

THE HOOT Volume 1 October 2017 the Trip of a Lifetime by Elizabeth Mcgowan

THE HOOT Volume 1 October 2017 The Trip Of A Lifetime By Elizabeth McGowan Timberlane gives many opportunities to students throughout the year. They give opportunities to go to shows, to get scholarships, and even to travel. This past summer one of these trips gave six Timberlane students the opportunity of a lifetime. On June 26th 2017, six Timberlane High School students and one chaperone boarded the airplane that brought them to Tanzania, Africa for 10 days, and these 10 days were days that they would never forget. However, the students preparation for this trip began long before June 26th. With a new country comes new diseases. In Tanzania there are many different diseases and viruses that you can contract that are very rare to get in the United States. For example, diseases and viruses such as malaria, hepatitis a, and typhoid are all much more common in Tanzania. Therefore, before going to Africa the students on the trip had to get the hepatitis a, and typhoid vac- cine, as well as take a malaria pill when they were on the trip. Tanzania, Africa is a very different place than the United States is. For example, in the United States you can rarely walk down the street without seeing someone in shorts, or a tight shirt. Howev- er, in Tanzania they are required to wear pants and it is looked down upon if you choose to wear tight clothing. Therefore, the students attending this trip packed solely pants, and loose shirts for the trip. TRHS Students Left to Right: Sam Valorose, Nate Alexander, Ryan Monahan, Julia Ramsdell, Story continued on Page 4 Caroline Diamond, and Hannah Sorenson An Exchange of Cultures A Freshman Adventure By Kayla Bowen By Maria Heim This years freshman are off with the sound of a horn! No, not the bells, the class trip to Adventurelore! Located in Danville, NH, the excursion took place in four waves of students from Monday, September 11th, to Thursday, September 14, 2017. -

September-October 1972

«fc4DE \ PET HEAL'. BOWSER goes'.to ' college How Important are LaboratorjfJests ? VANISHING • SPECIES "1V3 'VU3AIU OOld 09906 eiujojjieo V9l ON HW«3d aivd 3ovisod sn pjeA9|nog peawasou 8C88 "QUO lldOUdNON uoijepunoj mieaH lewmv EDITOR'S NOTEBOOK NOTE: We are very sorry the first half of the article on the "Animal Health Foundation" was inadvertently omit ted in the July-August issue. It ap pears in this issue. Ed. People who are interested in a future professional life which is rewarding and profitable should look into the possibility of entering the "Para Veterinary Medical" profession. During the past two decades there has been a tremendous increase in the (SSSfljjfeiDE demands of Veterinary Medicine, and Official Journal of the Animal Health Foundation on animal care and hearth. the profession has been over-burdened trying to fill these demands with grad SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 1972 Volume 3 Number 5 uate veterinarians. Educational institutions cannot fill ARTICLES these vacancies due to a lack of monies and the faculty necessary to expand Animal Health Care, Norene Harris 6 and admit more veterinary students Health Of The Cat And Its Relationship To The Owner, each year. The educational committees Louis J. Camuti, D. V.S 8 of the state and national associations The Man By The Road, Lee A very 10 have been researching the possibilities It's A Dog's Life Underground,/oe A lex Morris, Jr. 12 of training and licensing persons in the Animals Of The World, L. M. Fitzgerald 13 field of Para Veterinary Medicine. Vixens, Viruses, And Vaccines, James R. Olson 14 Heretofore state laws have limited The Show Must Go On- And Does, Hilarie Edwards 16 the type of duties of lay assistants and The City Child And The Zoo, Ellsworth Boyd 18 most of the veterinary duties had to be In Search of the Grizzly and Other Vanishing Species, performed by a graduate and licensed Thomas Snortum, D. -

2 Chainz Used 2 Free Download 2 Chainz Used 2 Free Download

2 chainz used 2 free download 2 chainz used 2 free download. Copyright All rights reserved II #Metime. Bài hát: Used 2 - 2 Chainz CD Universe is your source for 2 Chainz's song Used 2 MP3 download lyrics and much more. Listen and download now. Every verse is hard,” and she’s aint lying about that. Fabolous) Stream And “Listen to Mariah Carey – Money (feat. Stream ad-free or purchase CD's and MP3s now on Amazon.com. “Ya’ll gon’ love my verse. Sorry, this content is currently not available in your country due to its copyright restriction. Giấy phép MXH số 499/GP-BTTTT do Bộ Thông Tin và Truyền thông cấp ngày 28/09/2015.Giấy Chứng nhận Đăng ký Kinh doanh số 0305535715 do Sở kế hoạch và Đầu tư thành phố Hồ Chí Minh cấp ngày 01/03/2008. Music Download site Take a listen to the turnt up banger and let us know what you think. Download Used 2 mp3 Mp3, low quality, 0.9 Mb. 2 Chainz Used 2 Mp3 Download. Posted on May , 2018 August , 2018 by bryan63xy. Tìm . download 1 file . 2 Chainz Used 2 mp3 download free. 2 Chainz - Used 2 (Official Music Video) (Explicit) - YouTube Story is going to be extremely interesting, as soon as the artist prepared several intriguing collaborations SHOW ALL. 2 Chainz. Khi bật tính năng Autoplay, Bài hát được đề xuất sẽ tự động phát tiếp. B.O.A.T.S. ITEM TILE download. Next. The Ariana Grande-assisted track arrives exactly a month after their “7 rings (remix),” following multiple comparisons to 2 Chainz previous works. -

'Humble: Hikes to The

HOT Pa/HIP-HOP SONGSTM TOP R8LB/HIP-HOP ALBUMSnA nos TITLE CERTIFICATION Artist PEAK WKS ON LAST MIS ARTIST CERTIFICATION Title MUS OIL NO" FRODUCER (SONGWRITER) IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABEL POS CHART NIB NODO WIPIUMIDISTRAIUTING LABEL CHART THAT'S WHAT ILIKE 4 Bruno Mars 41 KENDRICK LAMAR DAMN. 5 23 IRS ILL , sPMEMNENLEIESSONWENWILEPOTI ARM TOP DAVIG/AFIERMAILMINIER5COPLAGA Justin Rielref heave. Chance The Ramer & hl Wayne DRAKE More Life 9 YOUNG MONEY/CASH MON ED/ REPU RI_ IC MACHINE GUN KELLY bloom 1 3 0 HUMBLE. Kendrick Lamar 13T19XX/13A0 BOY/INTERSCOPEOGA MIKE WILL MADE-IT (KLOUCKWORTH.M.L.WILLIAUS) TOP DAWG/AFTERUATH/INTERSCOPE 1 7 O BRUNOMARSA Z4K Magic 26 ATLANTIC/AG 0 4 MASK OFF A 3 13 METRO BOMAN (N.D.wiLBURN.L.T.WAYNO AUFREEBAFutureNDZ/EPIC 5 LOGIC Everybody 2 VISIONARY/REF JAM o 0 0 Tu88,1.w.LtICASXO TOUR LUF3 (SNOODS) 'Humble: GENERATIONlil few/ATLANTIC Uzi Vert 5 8 6 VARIOUS ARTISTS EPIC AF (Yellow/Pink) 3 EPIC CONGRATULATIONS Post Malone Featuring Quavo 6 23 CPO MUNN DUKESMETRO SO/AIM (APOST.L.BaL,A.PEENTIERMAPSHALL.LIWAYNELA.ROSENN) IEPUBLIC Hikes To MIGOS Culture 16 1 1 QUALITY CONTROL/300/AG 5 6 7 ISPY • KYLE Featuring Lil Yachty 3 21 IFORILLPIEGE mil Is.spiefut STIJEELOW/E1FORILLPIESEKALEJ INDIEPPILIWIYLPPY001101011MWITOJEILLITIL The Top POST MALONE A Stoney n REPUBLIC 7 8 s DNA. Kendrick Lamar 0 Kendrick Lamar scores his MIKE WILL MADE-IT (K.L.DUCKWORTLEALL.WILLIAMS) TOP DAWG/AFTERMATIVINTERSCOPE 3 5 9 FUTURE • FUTURE 13 A I/FREEBAND2/EPIC first No. 1on the Rhythmic o 9 LOCATION Khalid 8 20 airplay chart as "Humble." SMWEITSCSMASNOmeNsaLTLIPIIGEMICEINSCISISCRUGG5EILPAPPESAURIRELIGE,kGCNIALEI) -

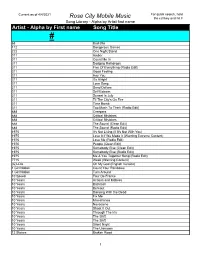

Alpha by First Name Song Title

Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title # 68 Bad Bite 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Amber 311 Count Me In 311 Dodging Raindrops 311 Five Of Everything (Radio Edit) 311 Good Feeling 311 Hey You 311 It's Alright 311 Love Song 311 Sand Dollars 311 Self Esteem 311 Sunset In July 311 Til The City's On Fire 311 Time Bomb 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 888 Creepers 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 The Sound (Clean Edit) 888 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 It's Not Living (If It's Not With You) 1975 Love It If We Made It (Warning Extreme Content) 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 1975 People (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) 1975 Me & You Together Song (Radio Edit) 7715 Week (Warning Content) (G)I-Dle Oh My God (English Version) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Burnout 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Novacaine 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years The Shift 10 Years The Shift 10 Years Silent Night 10 Years The Unknown 12 Stones Broken Road 1 Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975. -

Most Requested Songs of 2017

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2017 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Ronson, Mark Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Timberlake, Justin Can't Stop The Feeling! 4 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Mars, Bruno 24k Magic 9 V.I.C. Wobble 10 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 11 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 12 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 13 Sheeran, Ed Thinking Out Loud 14 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 15 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 16 Swift, Taylor Shake It Off 17 Mars, Bruno Marry You 18 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 19 Outkast Hey Ya! 20 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 21 Isley Brothers Shout 22 Earth, Wind & Fire September 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Williams, Pharrell Happy 25 Spice Girls Wannabe 26 Maroon 5 Sugar 27 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 28 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 29 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Legend, John All Of Me 32 Fonsi, Luis & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 33 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 34 Jordan, Montell This Is How We Do It 35 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 36 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 37 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 38 Temptations My Girl 39 Pitbull Feat. -

May 2017 Hitlist

MAY 2017 HITLIST Content Warning COMPILED FROM MEDIA CHARTS AND FEEDBACK Content Warning The Industry's WWW.PROMOONLY.COM #1 Source For Music & Music Video RADIO / TOP 40 DANCE / CLUB 1 Something Just Like... The Chainsmokers & ... MSR0417 1 Something Just Like... The Chainsmokers & ... MSC0517 2 That's What I Like Bruno Mars MSR0217 2 You Don't Know Me Jax Jones f./RAYE MSC0517 3 It Ain't Me Kygo & Selena Gomez MSR0417 3 Falling Alesso MSC0417 4 Stay Zedd & Alessia Cara MSR0417 4 I Love You Axwell _ Ingrosso f... MSC0417 5 Shape Of You Ed Sheeran MSR0217 5 One More Weekend Audien x MAX MSC0617 6 Say You Won't Let G... James Arthur MSR0117 6 Slide Calvin Harris f./Fr... MSC0517 7 Rockabye Clean Bandit & Anne... MSR0117 7 It Ain't Me Kygo & Selena Gomez MSC0517 8 Slide Calvin Harris MSR0417 8 I Need You Armin Van Buuren & ... MSC0417 9 Castle On The Hill Ed Sheeran MSR0517 9 Alone Alan Walker MSC0517 10 Paris The Chainsmokers MSR0217 10 Rich Boy Galantis MSC0517 11 Cold Maroon 5 MSR0417 11 Don't Give Up Morgan Page f./Liss... MSC0117 12 Now Or Never Halsey MSR0517 12 You're Not Alone Scotty Boy & Lizzie... RC0517 13 Sign Of The Times Harry Styles MSR0517 13 Solo Dance Martin Jensen RC0117 14 Passionfruit Drake MSR0517 14 Easy Go Grandtheft & Delane... MSC0217 15 Heavy Linkin Park MSR0417 15 Lady Austin Mahone f./Pi... RC0317 16 There's Nothing Hol... Shawn Mendes MSR0617 16 Find Me Sigma f./Birdy AC0417 17 iSpy Kyle MSR0317 17 Lost Love Lisa Cole MSC0617 18 Despacito Luis Fonsi & Daddy .. -

HIP-HOP SONGS TM TOP R&B/HIP-HOP Albunisna

HOT R&B/HIP-HOP SONGS TM TOP R&B/HIP-HOP ALBUNISnA 2 WES. LAST MS TITLE CERTIFICATION Artist PEAK WON ON LAST ARTIST CERTIFICATION Title WEAN AGO WEEK WEEK RomucEN (SONGWRITER) IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABEL POS DeET NEE« ONINtOTI/DISTROUTINGLABEL CHART 17 0 On Bruno Mars BRUNO MARS A 24K Magic THAT'S WHAT ILIKE 14 ,, .0 MARIPMANPUICLI.C.LOROWN...) ATLANTIC 1 ATLANTIC/AG FUTURE FUTURE 2 BAD AND BOUJEE A Migos Featuring Lil Uzi Vert 1 19 A 1/FREEBANOZ/EPIC METRO BOOMIN,G KOOP OCCEPOUSW.K.MA RS HALL.LT.WAYNE.R.MANDELL) DUALITY CONTROL/300 16 0 DG I FEEL IT COMING The Weeknd Featuring Daft Punk 3 17 0 V, RteluEcE K N D StarboY 6 6 DAFT PUNK.DOC PACK INNEY.0 IRKUT.THE BERND (A.TESEME.T.BANGALT FR ...) XO/RERIELIC 4 MIGOS Culture 7 0 TUNNEL VISION Kodak Black 4 CeiALITY CONTROL/300/AG 0 1111101100NIUNIEUENEUIEARNOCIAN.IINANE.1/14N1100401/1111411)01/111.0) KUM NCENZATINOK 5 FUTURE HNDRXX 3 EAUFREEBANOZ/EPIC 5 LOVE ON THE BRAIN A 26 Mars Tops 0 F.BALL (F.BALLIANGEL.R.FENTY) WESTBURY ROAD/ROCRihanna NATION 6 BIG SEAN IDecided. a G.0.0.0./DEF mil 0 ISPY KYLE Featuring Lil Yachty 6 12 0 IFORTILLOLKALE (K.HARVEYLIL YACHTY) INDIE.POP/OUALITYCONTRIX/MOTOY/N/CAPITOIJATLANTK R&B/ 14 0 0 REPUBLICPOST MALONE • Stoney 7 BOUNCE BACK • Big Sean 5 19 HI TMAKA (S.M.ANDERSON,C.WARD,L AYNE,AL,JOHRON,I.P.FELTOPEK.OWES1) CAO.O.CE/DEE IAN Hip-Hop s KHAUD American Teen 2 - RIGHT HAND/RCA HOT SHOT 411% NO FRAUDS Nicki Minaj, Drake & Lil Wayne 0 DEBUT 91.11/ WREN WAT? ATO (01/14E41.0.CARIERAIAMMIATNAZIANN TOUNGMCIEWASIIMONEWIEPUILE 8 1 9 DRAKE A Views 46 Songs YOUNG MONEY/CASH MONEY/REPUBLIC 0 MASK OFF 9 4 METRO BOOMS) (N.D.WILHURN.L.T.WAYNE) A-1/FREE8AFuture NC?/EPIC Bruno Mars scores his 17 0 0 to VARIOUS ARTISTS The RCA-List, Vol 4 6 first chart -topper on the 10 24K MAGIC Bruno Mars 3 17 10 8 A SHAMPOO PRESS & CURL (BRUNO MARS.P.M.LAWRENCE II.C.B.HROWN) ATLANTIC 11 II RIHANNA A ANTI 59 Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs WESTBURY ROAD/ROC NATION chart as "That's What I T-SHIRT Migos 12 0 0 11 9 NONON.RACKIEVI BOYMARSHALE.K.CEPHEISKA.OACLIBROSSECERACKLAY) BURRY CONTRIX/300 0 0 TRAY5 SCOTT.