Brian Walter's Swartkops Poems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presence, Levels and Distribution of Pollutants in the Estuarine Food Web- Swartkops River Estuary, South Africa

Presence, levels and distribution of pollutants in the estuarine food web- Swartkops River Estuary, South Africa L Nel 21250642 Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Magister Scientiae in Zoology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University Supervisor: Prof H Bouwman Co-supervisor: Dr N Strydom September 2014 1 “Man can hardly even recognize the devils of his own creation” ~ Albert Schweitzer i Presence, levels and distribution of pollutants in the estuarine food web- Swartkops River Estuary, South Africa Acknowledgements The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the help and support from a number of people. To each who played a role, I want to personally thank you. To my parents, Pieter and Monique Nel, there is not enough ways to say thank you for the support, inspiration and unconditional love, for always being there and having the faith to see this through when I was no longer able to. The assistance and advice I have received from my supervisors Prof Henk Bouwman and Dr Nadine Strydom. Thank you for your guidance, patience and valuable contributions. To Anthony Kruger and Edward Truter who assisted with the collection of the fish. Your generosity and assistance was unbelievable and without you, I would be nowhere near complete. To Sabina Philips who helped and assisted throughout the time I was in Port Elizabeth. Your help, kindness and friendship are greatly appreciated. Paula Pattrick who took the time to help with the seine nets for the collection of smaller fish. To Deon Swart for the arrangement of the collecting permits and dealing with difficult authorities To my friends and family for their trust, support and encouragement. -

Site Development Plans Standard Operating Procedures for COVID

NELSON MANDELA BAY METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY NOTICE SITE DEVELOPMENT PLAN APPLICATIONS (SDP) STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES FOR DURING COVID-19 PERIOD A. SITE DEVELOPMENT PLANS (SDPs) 1. SDP applications are to be converted into PDF format PDF (not exceeding 2mb) and submitted per email to the Planning Support Officer Ms N Ketelo at: [email protected], who will in turn acknowledge receipt of the application per email. 2. In the event that the attachments combined exceeds the prescribed size, the application must be split into separate emails or put in a flash-drive to be delivered to Land Planning Division in 3rd Floor Lillian Diedericks Building, 191 Govan Mbeki Avenue, Port Elizabeth, preferably on appointment. 3. Documents must be labelled Annexure A, B, C…etc. as guided by the table appended hereto showing documents required. 4. An assessment sheet will be emailed back to an applicant by a Town Planner dealing with the SDP. 5. It is the responsibility of an applicant to obtain comments from various municipal departments. 6. An applicant must make amendments to the plan as per comments received from various municipal departments, if required. 7. An applicant must submit the plan and the assessment sheet in PDF (email or flash-drive) to a Town Planner dealing with SDP through email. 8. A Town Planner will acknowledge receipt, finalize the SDP and communicate the outcome to an applicant through a correspondence sent via email. B. TOWN PLANNING COMMENTS ON BUILDING PLANS 1. Technical Controllers responsible for Town Planning related comments made on building plans will be available on Thursdays for inquiries at 3rd Floor Lillian Diedericks Building, Govan Mbeki Avenue, Port Elizabeth. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Adler, G. and Webster, E. (eds.) (2000) Trade Unions and Democratization in South Africa 1985±1998. London: Macmillan. Adler, J. (1994) `Life in an Informal Settlement'. Urban Forum, vol. 5, no. 2. Altbeker, A. and Steinberg, J. (1998) `Race, Reason and Representation in National Party Discourse, 1990±1992', in D. Howarth and A. Norval, (eds.) South Africa in Transition: New Theoretical Perspectives. London: Macmillan. Althusser, L. (1990) Philosophy and the Spontaneous Philosophy of the Scientists and Other Essays. London: Verso. Anacleti, O. (1990) `African Non-Governmental OrganisationsÐDo They Have a Future?' in Critical Choices for the NGO Community: African Development in the 1990s. Centre for African Studies, University of Edinburgh. ANC (African National Congress). (1980) `Strategies and Tactics', in B. Turok (ed.) Revolutionary Thought in the 20th Century. London: Zed Press. ANC (1985) Kabwe Consultative Conference. Unpublished minutes from the Commissions on Cadre Development and Strategies and Tactics. ANC (1986) `Attack! Attack! Give the Enemy No Quarter. Annual anniversary statement by the national executive committee of the ANC, 8 January 1986'. Sechaba, March edition. ANC (1994) The Reconstruction and Development Programme. Johannesburg: Uma- nyano Publications. Anon. (1985) `Building a tradition of resistance'. Work in Progress, no. 12. Anyang'Nyong'o, P. (ed.) (1987) Popular Struggles for Democracy in Africa. London: Zed Press. Atkinson, D. (1991) `Cities and Citizenship: Towards a Normative Analysis of the Urban Order in South Africa, with Special Reference to East London, 1950±1986'. Ph.D. thesis, University of Natal. Atkinson, D. (1992) `Negotiated Urban Development: Lessons from the Coal Face'. Centre for Policy Studies research report no. -

Luc Strydom Environmental Consultant

SRK Consulting Page 1 Luc Strydom Environmental Consultant Profession Environmental Scientist Education BA Environmental Management, University of South Africa, 2015 Registrations/ Registered EAP, EAPASA (2020/1504) Affiliations Certificated Natural Scientist (EIA), SACNASP (Reg No. 120385) Member, South African Wetland Society (Membership No.: 193665) Member, International Association of Impact Assessors, South Africa (IAIAsa), Volunteer, Custodians of Rare and Endangered Wildflowers (CREW). Specialisation Wetland and aquatic impact assessments, botanical surveys, vegetation impact assessments, invasive alien monitoring and control plans, rehabilitation plans, environmental impact and basic assessments, environmental management programmes (EMPrs), water use license applications (WULAs), environmental auditing (environmental control officer), geo-hydrological sampling, section 24G applications & GIS systems. Expertise Luc Strydom has previous experience in GIS, working for Setplan PE, a town planning consultancy group. His expertise in GIS includes map production, data capturing, data manipulation, data acquisition and database management. Luc has developed his skills and expertise over the years as he has been involved in many different types of environmental projects, such as: • environmental impact assessments (EIAs); • wetland and aquatic impact assessments (wetland screening, delineation, PES & EIS determination, ecosystem services assessment, etc.); • environmental management plans/programmes (EMPr); • environmental auditing (acting -

7. Impofu Grid Connection Rev Paleontology Report.Pdf

1 PALAEONTOLOGICAL HERITAGE: COMBINED DESKTOP & FIELD-BASED BASIC ASSESSMENT Grid connection for the proposed Impofu North, Impofu West & Impofu East Wind Farms near Humansdorp, Eastern Cape John E. Almond PhD (Cantab.) Natura Viva cc, PO Box 12410 Mill Street, Cape Town 8010, RSA [email protected] August 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The present report provides a palaeontological heritage Basic Assessment of the proposed Impofu grid connection. This includes (a) the approximately 120 km-long, 2 km-wide 132 kV grid connection corridor between the proposed Impofu North, Impofu West and Impofu East Wind Farms and the national grid in the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality (NMBM) near Port Elizabeth, Eastern Cape. Potential impacts of the proposed new Impofu collector switching station, wind farm switching stations and short 132 kV transmission lines linking them to the collector switching station as well as of substation extension areas are also considered. The report is based on a combined desktop and field-based study of the preferred grid connection corridor, incorporating a 2 km wide zone, with a special focus on areas underlain by potentially fossiliferous bedrocks. The grid connection study area is underlain by several formations of potentially fossiliferous sediments of the Gamtoos Group, Cape Supergroup, Uitenhage Group and Algoa Group (Sections 6 & 7, Table 1). However, on the southern coastal platform most of the fossils originally preserved in these bedrocks appear to have been destroyed by tectonic deformation and deep chemical weathering. The overlying Late Caenozoic superficial sediments such as alluvium, soils and ferricretes, are likewise of low palaeontological sensitivity. Relict patches of Plio-Pleistocene aeolianites (wind-blown sands) of the Nanaga Formation (Algoa Group) present in the subsurface on the interior coastal platform contain Early Stone Age artefacts but any associated fossils such as mammalian remains, or terrestrial gastropods have probably been destroyed by weathering here. -

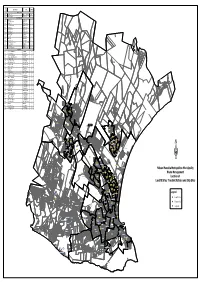

Map of Landfill Transfer and Skip Sites

Origin DESCRIPTION AREA WARD Code LANDFILL SITES G01 ARLINGTON PORT ELIZABETH 01 G02 KOEDOESKLOOF UITENHAGE 53 TRANSFER SITES G03 TAMBO STR McNAUGHTON 50 G04 GILLESPIE STR EXT UITENHAGE 53 G05 JOLOBE STR KWANOBUHLE 47 G06 ZOLILE NOGCAZI RD KWANOBUHLE 45 G07 SARILI STR KWANOBUHLE 42 G08 VERWOERD RD UITENHAGE 51 G09 NGEYAKHE STR KWANOBUHLE 42 G10 NTAMBANANI STR KWANOBUHLE 47 G11 LAKSMAN AVE ROSEDALE 49 G12 RALO STR KWAMAGXAKI 30 G13 GAIL ROAD GELVANDALE 13 G14 DITCHLING STR ALGOA PARK 11 G15 CAPE ROAD - OPP HOTEL HUNTERS RETREAT 12 G16 KRAGGAKAMA RD FRAMESBY 09 G17 5TH AVENUE WALMER 04 G18 STRANDFONTEIN RD SUMMERSTRAND 02 SKIP SITES G19 OFF WILLIAM MOFFAT FAIRVIEW 06 G20 STANFORD ROAD HELENVALE 13 G21 OLD UITENHAGE ROAD GOVAN MBEKI 33 G22 KATOO & HARRINGTON STR SALTLAKE 32 G23 BRAMLIN STREET MALABAR EXT 6 09 G24 ROHLILALA VILLAGE MISSIONVALE 32 G25 EMPILWENI HOSPITAL NEW BRIGHTON 31 G26 EMLOTHENI STR NEW BRIGHTON 14 G27 GUNGULUZA STR NEW BRIGHTON 16 G28 DAKU SQUARE KWAZAKHELE 24 G29 DAKU SPAR KWAZAKHELE 21 G30 TIPPERS CREEK BLUEWATER BAY 60 G31 CARDEN STR - EAST OF RAILWAY CROSSING REDHOUSE 60 G32 BHOBHOYI STR NU 8 MOTHERWELL 56 G33 UMNULU 1 STR NU 9 MOTHERWELL 58 Farms Uitenhage G34 NGXOTWANE STR NU 9 MOTHERWELL 57 G51 ward 53 S G35 MPONGO STR NU 7 MOTHERWELL 57 G36 MGWALANA STR NU 6 MOTHERWELL 59 G37 DABADABA STR NU 5 MOTHERWELL 59 G38 MBOKWANE NU 10 MOTHERWELL 55 Colchester G39 GOGO STR NU 1 MOTHERWELL 56 G40 MALINGA STR WELLS ESTATE 60 G41 SAKWATSHA STR NU 8 MOTHERWELL 58 G42 NGQOKWENI STR NU 9 MOTHERWELL 57 G43 UMNULU 2 STR NU 9 MOTHERWELL -

DOWNLOAD the APP 94 95 Overview of Nelson Mandela Bay

AuthenticAuthentic ExperiencesExperiences addo river safaris addo full day tours addo half day tours Test-drive our technology! Our revamped AutoPavilion features: • A kids’ experiential zone with driving simulators, colouring-in stations, ttoouurr,, ssaaffaarrii && aaddvveennttuurree ssppeecciiaalliissttss interactive displays and more • The newest addition to our much-loved Beetle family, Foxy Lady Disco Queen • The only Volkswagen XL1 hybrid concept car in South Africa • Visit the gift shop and take home your addo eco quad biking beach safari’s, sandboarding sledding and ferry rides piece of our Volkswagen brand Opening hours: Weekdays 08h30 - 16h00 and every first Saturday of the month 10h00 - 13h00. Closed all other weekends and public holidays. Open for all ages…Beetle fans especially welcome! fresh & salt water fishing river conservation & hiking birdwatching & photography www.crisscrossadventures.co.za CrisscrossAddo [email protected] +27 (0)83 330 0480 Crisscross Adventures - Addo CrissCross_Adventures 3 CONTENTS HALLO FROM NELSON MANDELA BAY 8 - 15 Warm Welcome 8 NMBT’s Visitor Information Centre’s 9 Tribute to Nelson Mandela 10 Important Information 12 – 14 Practical Safety Tips 15 HISTORICAL ATTRACTIONS 16 - 23 Port Elizabeth 16 - 20 Despatch 21 Uitenhage 22 - 23 WONDERFUL WILDLIFe and NATURE 24 - 33 Game Viewing 4, 24 - 29 Adventure Activities 2, 30 – 31, 37 The Great Outdoors 32 - 33 BEACHES, WATERSPORT and SPORTS 34 - 43 Beautiful Beaches 34 - 35 Wind & Watersport 36 – 39, 95 Dolphin Capital 40 Sports Scene -

Land Use Management System for the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality

TOWARDS A NEW LAND USE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM FOR THE NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY COMPONENT 1 : ANALYSIS & POLICY DIRECTIVES PHASES 1, 2 & 3 OUTCOMES REPORT (1ST DRAFT : FEBRUARY 2005) Prepared by: Prepared for: Business Unit Manager: Housing and Land Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality Mr J. van der Westhuysen i Executive Summary 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION Drafting of a New Land Use Management System (LUMS) for the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality, which should include as a minimum requirement a single zoning scheme for the Metro‟s area of jurisdiction, has been identified as a priority project in the Metro‟s 2003/4 Integrated Development Plan (IDP). 1.2 PROBLEM STATEMENT With the amalgamation of the Rural Areas, Uitenhage, Despatch and Port Elizabeth, in 2000, the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality inherited twelve (12) different sets of zoning schemes. These zoning schemes are currently administered and implemented by the Municipality and in some cases delegation vests with the Department of Housing, Local Government and Traditional Affairs. These zoning schemes, some dating back to 1961, were prepared and promulgated in terms of various sets of legislation, i.e. the Land Use Planning Ordinance and the regulations promulgated in terms of the Black Communities Development Act. In many respects, these existing zoning schemes are inappropriate and outdated and therefore do not respond to current and identified future land development and conservation needs. The White Paper on Spatial Planning and Land Use Management clearly summarises shortfalls relating to land use planning and management in general: . Disparate Land Use Management Systems in Former “Race Zones” . Old and outdated Land Use Management . -

Download Resource Register

Province of the EASTERN CAPE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Private Bag / Privaatsak X3906, Struanway, Struandale, Port Elizabeth, 6056 Tel. No. (041) 4065732 - Fax. No. (041) 4511729 / 4513458 [email protected] NELSON MANDELA METROPOLE DISTRICT OFFICE RESOURCE REGISTER July 2008 The District Manager 041-4065701 041-4513458 Department of Social Development Private Bag x3906 Port Elizabeth 6056 Programme Management Unit 041- 4065700 041-4513458 People with special needs (disability, older 041-4065700 041-4513458 persons, substance abuse) Substance abuse and disability 041-4065700 041-4513458 Older persons 041-4065700 041-4513458 Women and Victim Empowerment 041-4065700 041-4513458 HIV/AIDS 041-4065700 041-4513458 Child, Youth, family 041-4065700 041-4513458 Early Childhood Development 041 406 5700 041 4511729 041 406 5782 Development services 041-4065700 041-4513458 2 DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT NELSON MANDELA METROPOLE DISTRICT COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CENTRES SERVICES OFFERED: Development, Care & Protection of Vulnerable People in the Community OFFICE POSTAL ADDRESS STREET ADDRESS TEL. NO. FAX. AREAS NO. UITENHAGE P.O. Box 538, Uitenhage Spoornet Building 9228838 9228957 Uitenhage, Despatch and surrounding rural area 6230 Stow Road (Amanzi, Cockscomb, Kruis River Elands River) Uitenhage ZWIDE Private bag X 3906, Port Struanway, New Brighton 4065700 4511729 Kwazakhele, North of Daku Road, Kwadesi, Elizabeth 6056 Kwamagxaki, Zwide, Missionvale, Joe Slovo, Govan Mbeki BETHELSDORP Private bag X 3906, Port Straunway, -

The Hydrogeology of the Uitenhage Artesian Basin with Reference to the Table Mountain Group Aquifer

The hydrogeology of the Uitenhage Artesian Basin with reference to the Table Mountain Group Aquifer LGA Maclear SRK Consulting Engineers and Scientists, PO Box 21842, Port Elizabeth 6000, South Africa Abstract The Uitenhage Artesian Basin (UAB) lies in the Eastern Cape and is South Africa’s most important artesian groundwater basin, supplying approximately 1 400 Ml/yr (44 l/s) of water from springs for domestic use to Uitenhage, as well as supporting large citrus irrigation schemes. Groundwater from this basin has been extensively utilised from the early part of the 20th century, including periods of over-exploitation resulting in the declaration of a groundwater control area to limit abstraction to sustainable rates. The aquifer comprises fractured Table Mountain Group (TMG) sandstones confined in the eastern part of the basin by overlying Cretaceous siltstones and mudstones, resulting in artesian conditions. The Coega Fault is a major structural feature dividing the basin into separate systems, viz. the southern Swartkops Aquifer and the northern Coega Ridge Aquifer, that are hydrogeologically independent of each other. The Elands River syncline divides the Swartkops Aquifer further into the Kruisrivier and Bethelsdorp Units. Borehole yields commonly range from 5 to 10 l/s and the groundwater quality is excellent with low salinities. Water hardening, however, is required due to the acidic and corrosive nature of the groundwater, typical of other Table Mountain Group aquifers in South Africa. Using 14C data, the age of the groundwater in the basin ranges from 1 500 to 28 000 years with a calculated flow rate of 0.8 m/a. -

Survey of Heavy Metals in the Sediments of the Swartkops River Estuary, Port Elizabeth South Africa

Survey of heavy metals in the sediments of the Swartkops River Estuary, Port Elizabeth South Africa Karen Binning and Dan Baird* Zoology Department, University of Port Elizabeth, PO Box 1600, Port Elizabeth 6000, South Africa Abstract Elevated levels of heavy metals in the sediment can be a good indication of man-induced pollution. Concentrations of chrome, lead, zinc, titanium, manganese, strontium, copper and tin were measured in the sediments taken along a section of the Swartkops River and its estuary. These results showed that the highest heavy metal concentrations in both the estuary and river were recorded at points where runoff from informal settlements and industry entered the system. Comparison of the results for the estuary with those obtained in a similar survey made about 20 years ago revealed some remarkable increases. This raises concern over the long-term health of the Swartkops River ecosystem. Introduction pollution in a particular region or ecosystem. Heavy metal concentrations in the water column can be relatively low, but the The Swartkops River flows through a highly urbanised and concentrations in the sediment may be elevated. Low level discharges industrialised region of the Eastern Cape and forms an integral part of a contaminant may meet the water quality criteria, but long-term of Port Elizabeth and the surrounding areas. It is a valuable partitioning to the sediments could result in the accumulation of recreational and ecological asset, but owing to the rapidly expanding high loads of pollutants. It has been estimated that about 90% of urban areas, it is subject to the effects and influences of these particulate matter carried by rivers settles in estuaries and coastal developments. -

2020 1. Size of Nelson Mandela Bay's Residential Property Market

NELSON MANDELA BAY Housing Market Report - 2020 1. Size of the residential property market Summary: There are approximately 368 520 households in Nelson Mandela Bay 2. Impact of COVID-19 (NMB). The city’s residential property market includes rental properties, where 3. Government-subsidised properties (GSP) more than one family might live in a property with a single title deed – for example, a high-rise building. In addition, there are an estimated 38 000 4. Residential transactions — new build households living in informal settlements.1 These are not reflected in this data, 5. Residential transactions — resale which only considers formally registered residential properties. 6. Residential transactions — GSP NMB’s residential property market was valued at R136.7 billion in 2019, with 67% 7. First-time homeowners/buyers of properties valued at R600 000 or less. 42% are government-subsidised—the 8. Housing finance — new vs resale largest share of all the metros. The contribution of government housing (75%) was evident in the entry market. Only 9% of total transactions were new build 9. Housing finance — by lender properties, while the resale market was more active. FNB and Standard Bank 10. Freehold vs. sectional title properties issued the largest share of their bonded transactions for properties valued below 11. Comparing across metros R300 000. Overall, bonded transactions in the entry market are expected to 12. Report methodology remain low due to unequal economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. 1. Size of Nelson Mandela Bay’s residential property market In 2019, there were 239 181 residential properties on the deeds registry in Nelson Mandela Bay (NMB), making up 35.1% of the total residential properties in the Eastern Cape province.