Dispelling Misperceptions of Native Lampreys (Entosphenus and Lampetra Spp.) in the Pacific Northwest (USA)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 NORTHERN CALIFORNIA BROOK LAMPREY Entosphenus Folletti

NORTHERN CALIFORNIA BROOK LAMPREY Entosphenus folletti (Valdykov and Kott) Status: High Concern. The northern California brook lamprey has a very limited known distribution and aquatic habitats within their range are heavily altered by agriculture and grazing. Their actual distribution and abundance is unknown. Description: This lamprey is a non-predatory species that has an adult size of 17-23 cm in total length (Vladykov and Kott 1976b, Renaud 2011). Adult disc length is 6.6–7.8% of total length and the trunk myomere count is 61-65. The following description of dentition is from Renaud (2011, p. 27): “supraoral lamina, 3 unicuspid teeth, the median one smaller than the lateral ones; infraoral lamina, 5 unicuspid teeth; 4 endolaterals on each side; endolateral formula, typically 2–3–3–2, the fourth endolateral can also be unicuspid; 1–2 rows of anterials; first row of anterials, 2 unicuspid teeth; exolaterals absent; 1 row of posterials with 13–18 teeth, of which 0–4 are bicuspid and the rest unicuspid (some of these teeth may be embedded in the oral mucosa); transverse lingual lamina, 14-20 unicuspid teeth, the median one slightly enlarged; longitudinal lingual laminae teeth are too poorly developed to be counted. Velar tentacles, 8–9, with tubercles. The median tentacle is about the same size as the lateral ones immediately next to it…Oral papillae, 13.” Ammocoetes are described in Renaud (2011). The northern California brook lamprey is similar to the Pit-Klamath brook lamprey, with which it co-occurs, but is somewhat larger (most are >19 cm TL), has a larger oral disk (<6% of TL vs >6% of TL), and has elongate velar tentacles without tubercles. -

Review of the Lampreys (Petromyzontidae) in Bosnia and Herzegovina: a Current Status and Geographic Distribution

Review of the lampreys (Petromyzontidae) in Bosnia and Herzegovina: a current status and geographic distribution Authors: Tutman, Pero, Buj, Ivana, Ćaleta, Marko, Marčić, Zoran, Hamzić, Adem, et. al. Source: Folia Zoologica, 69(1) : 1-13 Published By: Institute of Vertebrate Biology, Czech Academy of Sciences URL: https://doi.org/10.25225/jvb.19046 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non - commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Journal-of-Vertebrate-Biology on 13 Feb 2020 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Journal of Open Acces Vertebrate Biology J. Vertebr. Biol. 2020, 69(1): 19046 DOI: 10.25225/jvb.19046 Review of the lampreys (Petromyzontidae) in Bosnia and Herzegovina: -

Simple Genetic Assay Distinguishes Lamprey Genera Entosphenus and Lampetra: Comparison with Existing Genetic and Morphological Identification Methods

North American Journal of Fisheries Management 36:780–787, 2016 © American Fisheries Society 2016 ISSN: 0275-5947 print / 1548-8675 online DOI: 10.1080/02755947.2016.1167146 MANAGEMENT BRIEF Simple Genetic Assay Distinguishes Lamprey Genera Entosphenus and Lampetra: Comparison with Existing Genetic and Morphological Identification Methods Margaret F. Docker* Department of Biological Sciences, University of Manitoba, 50 Sifton Road, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N2, Canada Gregory S. Silver and Jeffrey C. Jolley U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Columbia River Fisheries Program Office, 1211 Southeast Cardinal Court, Suite 100, Vancouver, Washington 98683, USA Erin K. Spice Department of Biological Sciences, University of Manitoba, 50 Sifton Road, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N2, Canada Along the West Coast of North America, the lamprey genera Abstract Entosphenus and Lampetra co-occur from Alaska to California Several species of lamprey belonging to the genera (Potter et al. 2015). Six species have been described in the genus Entosphenus Lampetra and , including the widely distributed Entosphenus (including the widely distributed PacificLamprey PacificLampreyE. tridentatus and Western Brook Lamprey L. richardsoni, co-occur along the West Coast of North E. tridentatus). In the genus Lampetra, four species are formally America. These genera can be difficult to distinguish morpho- recognized in North America (including the widely distributed logically during their first few years of larval life in freshwater, Western Brook Lamprey L. richardsoni), although the presence thus hampering research and conservation efforts. However, of genetically distinct populations of Lampetra spp. in Oregon fi existing genetic identi cation methods are time consuming or and California suggests the occurrence of additional, currently expensive. -

Redescription of Eudontomyzon Stankokaramani (Petromyzontes, Petromyzontidae) – a Little Known Lamprey from the Drin River Drainage, Adriatic Sea Basin

Folia Zool. – 53(4): 399–410 (2004) Redescription of Eudontomyzon stankokaramani (Petromyzontes, Petromyzontidae) – a little known lamprey from the Drin River drainage, Adriatic Sea basin Juraj HOLČÍK1 and Vitko ŠORIĆ2 1 Department of Ecosozology, Institute of Zoology, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dúbravská cesta 9, 845 06 Bratislava, Slovak Republic; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Faculty of Science, University of Kragujevac, R.Domanovića 12, 34000 Kragujevac, Serbia and Montenegro; e-mail: [email protected] Received 28 May 2004; Accepted 24 November 2004 A b s t r a c t . Nonparasitic lamprey found in the Beli Drim River basin (Drin River drainage, Adriatic Sea watershed) represents a valid species Eudontomyzon stankokaramani Karaman, 1974. From other species of the genus Eudontomyzon it differs in its dentition, and the number and form of velar tentacles. This is the first Eudontomyzon species found in the Adriatic Sea watershed. Key words: Eudontomyzon stankokaramani, Beli Drim River basin, Drin River drainage, Adriatic Sea watershed, West Balkan, Serbia Introduction Eudontomyzon is one of five genera that belong to the family Petromyzontidae occurring in the Palaearctic faunal region. Within this region the genus is composed of one parasitic and two non-parasitic species. According to recent knowledge, Europe is inhabited by E. danfordi Regan, 1911, E. mariae (Berg, 1931), E. hellenicus Vladykov, Renaud, Kott et Economidis, 1982, and also by a still unnamed but now probably extinct species of anadromous parasitic lamprey related to E. mariae known from the Prut, Dnieper and Dniester Rivers (H o l č í k & R e n a u d 1986, R e n a u d 1997). -

Volume III, Chapter 3 Pacific Lamprey

Volume III, Chapter 3 Pacific Lamprey TABLE OF CONTENTS 3.0 Pacific Lamprey (Lampetra tridentata) ...................................................................... 3-1 3.1 Distribution ................................................................................................................. 3-2 3.2 Life History Characteristics ........................................................................................ 3-2 3.2.1 Freshwater Existence........................................................................................... 3-2 3.2.2 Marine Existence ................................................................................................. 3-4 3.2.3 Population Demographics ................................................................................... 3-5 3.3 Status & Abundance Trends........................................................................................ 3-6 3.3.1 Abundance............................................................................................................ 3-6 3.3.2 Productivity.......................................................................................................... 3-8 3.4 Factors Affecting Population Status............................................................................ 3-8 3.4.1 Harvest................................................................................................................. 3-8 3.4.2 Supplementation................................................................................................... 3-9 3.4.3 -

Relationships Between Anadromous Lampreys and Their Host

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN ANADROMOUS LAMPREYS AND THEIR HOST FISHES IN THE EASTERN BERING SEA By Kevin A. Siwicke RECOMMENDED: Dr. Trent Sutton / / / c ^ ■ ^/Jy^O^^- Dr. Shannon Atkinson Chair, Graduate Program in Fisheries Division APPROVED: Dr.^Michael Castellini Sciences Date WW* RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN ANADROMOUS LAMPREYS AND THEIR HOST FISHES IN THE EASTERN BERING SEA A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Kevin A. Siwicke, B.S. Fairbanks, Alaska August 2014 v Abstract Arctic Lamprey Lethenteron camtschaticum and Pacific Lamprey Entosphenus tridentatus are ecologically and culturally important anadromous, parasitic species experiencing recent population declines in the North Pacific Ocean. However, a paucity of basic information on lampreys feeding in the ocean precludes an incorporation of the adult trophic phase into our understanding of lamprey population dynamics. The goal of this research was to provide insight into the marine life-history stage of Arctic and Pacific lampreys through lamprey-host interactions in the eastern Bering Sea. An analysis of two fishery-independent surveys conducted between 2002 and 2012 in the eastern Bering Sea revealed that Arctic Lampreys were captured in epipelagic waters of the inner and middle continental shelf and were associated with Pacific Herring Clupea pallasii and juvenile salmonids Oncorhynchus spp. In contrast, Pacific Lampreys were captured in benthic waters along the continental slope associated with bottom-oriented groundfish. Consistent with this analysis of fish assemblages, morphology of recently inflicted lamprey wounds observed on Pacific Cod Gadus macrocephalus was similar to morphology of Pacific Lamprey oral discs, but not that of Arctic Lamprey oral discs. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Lamprey, Hagfish

Agnatha - Lamprey, Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Super Class: Agnatha Hagfish Agnatha are jawless fish. Lampreys and hagfish are in this class. Members of the agnatha class are probably the earliest vertebrates. Scientists have found fossils of agnathan species from the late Cambrian Period that occurred 500 million years ago. Members of this class of fish don't have paired fins or a stomach. Adults and larvae have a notochord. A notochord is a flexible rod-like cord of cells that provides the main support for the body of an organism during its embryonic stage. A notochord is found in all chordates. Most agnathans have a skeleton made of cartilage and seven or more paired gill pockets. They have a light sensitive pineal eye. A pineal eye is a third eye in front of the pineal gland. Fertilization of eggs takes place outside the body. The lamprey looks like an eel, but it has a jawless sucking mouth that it attaches to a fish. It is a parasite and sucks tissue and fluids out of the fish it is attached to. The lamprey's mouth has a ring of cartilage that supports it and rows of horny teeth that it uses to latch on to a fish. Lampreys are found in temperate rivers and coastal seas and can range in size from 5 to 40 inches. Lampreys begin their lives as freshwater larvae. In the larval stage, lamprey usually are found on muddy river and lake bottoms where they filter feed on microorganisms. The larval stage can last as long as seven years! At the end of the larval state, the lamprey changes into an eel- like creature that swims and usually attaches itself to a fish. -

Rare and Sensitive Species: Status Summaries

RARE AND SENSITIVE SPECIES: STATUS SUMMARIES Narratives summarizing the status for 39 rare and mous fishes. Some rare and sensitive species are sensitive species were prepared. These narratives recognized as requiring special protection by are arranged in phylogenetic order and are divided the States of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, or as follows: Distribution and Status, Habitat Rela- Montana. Many are managed as sensitive spe- tionships, and Key Factors Influencing Status. cies by the USDA Forest Service and/or Accompanying each narrative is a map that typi- USDI Bureau of Land Management. Several cally illustrates the probable historic and current were considered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife distribution plus any major introduction sites Service to be Category 2 Candidates for listing mapped at the watershed level. The actual distri- until a February 27, 1996 nationwide decision butions of these species may include small por- to delete all Category 2 taxa from Candidate tions of the watersheds and therefore, are species status. overestimated on the figures. General categories of Although we know less about the rare and sensi- research and information needs are listed for each tive species than the seven key salmonids, analyses species in table 4.53 (see following section "Infor- of existing distribution and reviews of available mation and Research Needs." literature provide important insights about com- These status narratives include a variety of mon threats and appropriate management needs. narrowly distributed endemics, largely un- Many of these taxa occur in isolated areas of the known species, and other native species that Columbia River Basin, in isolated subbasins of the may be important and wide ranging but for Great Basin, or are restricted to the upper Klamath which the assessment area represents a small Basin. -

Lake Superior Food Web MENT of C

ATMOSPH ND ER A I C C I A N D A M E I C N O I S L T A R N A T O I I O T N A N U E .S C .D R E E PA M RT OM Lake Superior Food Web MENT OF C Sea Lamprey Walleye Burbot Lake Trout Chinook Salmon Brook Trout Rainbow Trout Lake Whitefish Bloater Yellow Perch Lake herring Rainbow Smelt Deepwater Sculpin Kiyi Ruffe Lake Sturgeon Mayfly nymphs Opossum Shrimp Raptorial waterflea Mollusks Amphipods Invasive waterflea Chironomids Zebra/Quagga mussels Native waterflea Calanoids Cyclopoids Diatoms Green algae Blue-green algae Flagellates Rotifers Foodweb based on “Impact of exotic invertebrate invaders on food web structure and function in the Great Lakes: NOAA, Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, 4840 S. State Road, Ann Arbor, MI A network analysis approach” by Mason, Krause, and Ulanowicz, 2002 - Modifications for Lake Superior, 2009. 734-741-2235 - www.glerl.noaa.gov Lake Superior Food Web Sea Lamprey Macroinvertebrates Sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus). An aggressive, non-native parasite that Chironomids/Oligochaetes. Larval insects and worms that live on the lake fastens onto its prey and rasps out a hole with its rough tongue. bottom. Feed on detritus. Species present are a good indicator of water quality. Piscivores (Fish Eaters) Amphipods (Diporeia). The most common species of amphipod found in fish diets that began declining in the late 1990’s. Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha). Pacific salmon species stocked as a trophy fish and to control alewife. Opossum shrimp (Mysis relicta). An omnivore that feeds on algae and small cladocerans. -

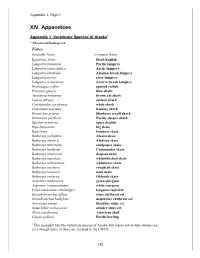

XIV. Appendices

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS. -

Pacific and Arctic Lampreys Pacific Lamprey (Entosphenus Tridentatus) (Gairdner, 1836) Family Petromyzontidae Pacific Lamprey (Entosphenus Tridentatus)

Pacific Lamprey 49 Pacific and Arctic Lampreys Pacific Lamprey (Entosphenus tridentatus) (Gairdner, 1836) Family Petromyzontidae Pacific Lamprey (Entosphenus tridentatus). Photograph by Note: Except for physical description and geographic range data, René Reyes, Bureau of Reclamation. all information is from areas outside of the study area. Colloquial Name: None within U.S. Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. Ecological Role: Its rarity in the U.S. Chukchi Sea and absence from the U.S. Beaufort Sea implies an insignificant role in regional ecosystem dynamics. Physical Description/Attributes: Elongate, eel-like body, blue-black to dark brown dorsally, pale or silver ventrally. For specific diagnostic characteristics, seeFishes of Alaska, (Mecklenburg and others, 2002, p. 61, as Lampetra tridentata) [1]. Swim bladder: Absent [2]. Antifreeze glycoproteins in blood serum: Unknown. Range: Eastern U.S. Chukchi Sea [1, 3]. Elsewhere, from Bering Sea south to Punta Canoas, northern Baja California, Commander Islands, and Pacific coast of Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia, and Honshu, Japan [1]. Relative Abundance: Rare in U.S. Chukchi Sea, with one record near Cape Lisburne, Alaska [1, 3]. Common in southeastern Bering Sea [6]. Widespread at least as far southward as Honshu, Japan [7]. Rare to occasional in marine waters off Commander Islands and Pacific coasts of Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia, and Hokkaido, Japan [1]. Pacific Lamprey Entosphenus tridentatus 170°E 180° 170°W 160°W 150°W 140°W 130°W 120°W 110°W 200 76°N Victoria Island ARCTIC OCEAN Banks 200 Island