Gender and Turkish-German Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reading Habits and Preferences of LGBTIQ+ Youth Rachel S

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Library Faculty Publications Library Services 2019 The Reading Habits and Preferences of LGBTIQ+ Youth Rachel S. Wexelbaum Saint Cloud State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/lrs_facpubs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Wexelbaum, Rachel S., "The Reading Habits and Preferences of LGBTIQ+ Youth" (2019). Library Faculty Publications. 62. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/lrs_facpubs/62 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Services at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Reading Habits and Preferences of LGBTIQ+ Youth Rachel Wexelbaum, St. Cloud State University, USA Abstract The author of this article presents the available findings on the reading habits and preferences of LGBTIQ+ youth. She will discuss the information seeking behavior of LGBTIQ+ youth and challenges that these youth face in locating LGBTIQ+ reading materials, whether in traditional book format or via social media. Finally, the author will provide recommendations to librarians on how to make LGBTIQ+ library resources more relevant for youth, as well as identify areas that require more research. Keywords: LGBT; LGBT library resources and services; reading; social -

Sfiff 2019 Program Here

SantaFeIndependent.com 2019 team and advisory board 2019 SFIFF TEAM Jacques Paisner Artistic Director Liesette Paisner Bailey Executive Director Jena Braziel Guest Service Director Derek Horne Director of Shorts Programmer Beau Farrell Associate Programmer Stephanie Love Office Manager Dawn Hoffman Events Manager Deb French Venue Coordinator Chris Bredenberg Tech Director Allie Salazar Graphic Designer Blake Lewis Headquarters Manager Castle Searcy Festival Dailies Adelaide Zhang Box Office Assistant Sarah Mease Box Office Assistant Eileen O’Brien MC Sage Paisner Photographer 2019 SFIFF ADVISORY BOARD Gary Farmer, Chair Chris Eyre Kirk Ellis David Sontag Alexandria Bombach Nicole Guillemet “A young Sundance” Alton Walpole —Indiewire Kimi Ginoza Green Paul Langland Beth Caldarello Xavier Horan “An all inclusive Marissa Juarez resort for cinephiles...” —Filmmaker Magazine “Bringing the community together” 505-349-1414 —Slant Magazine www.santafeindependent.com • [email protected] 418 Montezuma Ave. Suite 22 Santa Fe, NM 87501 3 AD AD welcome WELCOME Dear Santa Fe Independent Film Festival Visitors and Community, Welcome to Santa Fe, and to the festival The Albuquerque Journal calls “The Next Sundance.” The Santa Fe Independent Film Festival (SFIFF), now in its eleventh year, has become one of Santa Fe’s most celebrated annual events. I know you will enjoy SFIFF’s world-class programming and award-winning guests, including renowned ac- tors Jane Seymour and Tantoo Cardinal. I encourage you to investi- gate the many activities, museums, galleries, restaurants, and more that Santa Fe has to offer. The Santa Fe Independent Film Festival fills five days with screen- ings, workshops, educational panels, book signings, and celebra- tions. -

The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-5-2021 The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 Denali Elizabeth Kemper CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/661 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 By Denali Elizabeth Kemper Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2020 Thesis sponsor: January 5, 2021____ Emily Braun_________________________ Date Signature January 5, 2021____ Joachim Pissarro______________________ Date Signature Table of Contents Acronyms i List of Illustrations ii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Points of Reckoning 14 Chapter 2: The Generational Shift 41 Chapter 3: The Return of the Repressed 63 Chapter 4: The Power of Nazi Images 74 Bibliography 93 Illustrations 101 i Acronyms CCP = Central Collecting Points FRG = Federal Republic of Germany, West Germany GDK = Grosse Deutsche Kunstaustellung (Great German Art Exhibitions) GDR = German Democratic Republic, East Germany HDK = Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) MFAA = Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Program NSDAP = Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Worker’s or Nazi Party) SS = Schutzstaffel, a former paramilitary organization in Nazi Germany ii List of Illustrations Figure 1: Anonymous photographer. -

Situating German Multiculturalism in the New Europe

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 6-1-2011 A Country of Immigration? Situating German Multiculturalism in the New Europe Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Khrebtan-Hörhager, Julia, "A Country of Immigration? Situating German Multiculturalism in the New Europe" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 337. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/337 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. A COUNTRY OF IMMIGRATION? SITUATING GERMAN MULTICULTURALISM IN THE NEW EUROPE __________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager June 2011 Advisor: Dr. Kate Willink ©Copyright by Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager 2011 All Rights Reserved Author: Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager Title: A COUNTRY OF IMMIGRATION? SITUATING GERMAN MULTICULTURALISM IN THE NEW EUROPE Advisor: Dr. Kate Willink Degree Date: June 2011 Abstract This dissertation addresses a complex cultural and social phenomenon: German multiculturalism in the framework of the European Union in the century of globalization and global migration. I use selected cinematographic works by Fatih Akin, currently the most celebrated German and European filmmaker, as cultural texts. -

Rainer Werner Fassbinder Amor Y Rabia Coordinado Por Quim Casas

Rainer Werner Fassbinder Amor y rabia Coordinado por Quim Casas Colección Nosferatu Editan: E. P. E. Donostia Kultura Teatro Victoria Eugenia Reina Regente 8 20003 Donostia / San Sebastián Tf.: + 34 943 48 11 57 [email protected] www.donostiakultura.eus Euskadiko Filmategia – Filmoteca Vasca Edificio Tabakalera Plaza de las Cigarreras 1, 2ª planta 20012 Donostia / San Sebastián Tf.: + 34 943 46 84 84 [email protected] www.filmotecavasca.com Distribuye: UDL Libros Tf.: + 34 91 748 11 90 www.udllibros.com © Donostia Kultura, Euskadiko Filmategia – Filmoteca Vasca y autores ISBN: 978-84-944404-9-6 Depósito legal: SS-883-2019 Fuentes iconográficas: Rainer Werner Fassbinder Foundation, Goethe-Institut Madrid, StudioCanal, Beta Cinema, Album Diseño y maquetación: Ytantos Imprime: Michelena Artes Gráficas Foto de portada: © Rainer Werner Fassbinder Foundation Las amargas lágrimas de Petra von Kant © Rainer© Fassbinder Werner Foundation SUMARIO CONTEXTOS Presentación: amor y rabia. Quim Casas .......................................... 17 No había casa a la que volver. Fassbinder y el Nuevo Cine Alemán. Violeta Kovacsics ......................................... 31 En la eternidad de una puesta de sol. Carlos Losilla ........................... 37 El teatro, quizá, no fue un mero tránsito. Imma Merino ...................... 47 GÉNEROS, SOPORTES, FORMATOS, ESTILOS Experimentar con Hollywood y criticar a la burguesía Los primeros años del cine de Fassbinder Israel Paredes Badía ..................................................................... 61 Más frío que la muerte. El melodrama según Fassbinder: un itinerario crítico. Valerio Carando .............................................. 71 Petra, Martha, Effi, Maria, Veronika... El cine de mujeres de Fassbinder. Eulàlia Iglesias ........................................................ 79 Atención a esas actrices tan queridas. La puesta en escena del cuerpo de la actriz. María Adell ................................................ 89 Sirk/Fassbinder/Haynes. El espejo son los otros. -

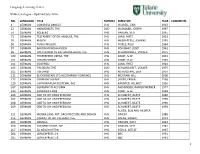

1 Language Learning Center Video Catalogue

Language Learning Center Video Catalogue – Updated July 2016 NO. LANGUAGE TITLE FORMAT DIRECTOR YEAR COMMENTS 4 GERMAN CONGRESS DANCES VHS CHARELL, ERIK 1932 22 GERMAN HARMONISTS, THE DVD VILSMAIER, JOSEPH 1997 54 GERMAN KOLBERG VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1945 71 GERMAN TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE, THE VHS LANG, FRITZ 1933 95 GERMAN MALOU VHS MEERAPFELE, JEANINE 1983 96 GERMAN TONIO KROGER VHS THIELE, ROLF 1964 97 GERMAN BARON MUNCHHAUSEN VHS VON BAKY, JOSEF 1943 99 GERMAN LOST HONOR OF KATHARINA BLUM, THE VHS SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 100 GERMAN THREEPENNY OPERA, THE VHS PABST, G.W. 1931 101 GERMAN JOYLESS STREET VHS PABST, G.W. 1925 102 GERMAN SIEGFRIED VHS LANG, FRITZ 1924 103 GERMAN TIN DRUM, THE DVD SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 105 GERMAN TIEFLAND VHS RIEFENSTAHL, LENI 1954 111 GERMAN BLICKKONTAKE (TO ACCOMPANY KONTAKE) VHS MCGRAW HILL 2000 127 GERMAN GERMANY AWAKE VHS LEISER, ERWIN 1968 129 GERMAN CAPTAIN FROM KOEPENIK, THE VHS KAUNTER, HELMUT 1956 167 GERMAN GERMANY IN AUTUMN VHS FASSBINDER, RANIER WERNER 1977 199 GERMAN PANDORA'S BOX VHS PABST, G.W. 1928 206 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 207 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 208 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 209 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 ROSEN, BOB AND ANDREA 211 GERMAN VIENNA 1900: ART, ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN VHS SIMON 1986 253 GERMAN CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, THE VHS WIENE, ROBERT 1919 265 GERMAN DAMALS VHS HANSEN, ROLF 1943 266 GERMAN GOLDENE STADT, DIE VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1942 267 GERMAN ZU NEUEN -

Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination EDITED BY TARA FORREST Amsterdam University Press Alexander Kluge Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination Edited by Tara Forrest Front cover illustration: Alexander Kluge. Photo: Regina Schmeken Back cover illustration: Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © T. Forrest / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustra- tions reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Alexander Kluge …and in memory of Miriam Hansen Table of Contents Introduction Editor’s Introduction Tara Forrest The Stubborn Persistence of Alexander Kluge Thomas Elsaesser Film, Politics and the Public Sphere On Film and the Public Sphere Alexander Kluge Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to G I A Miriam Hansen ‘What is Different is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge Heide -

United States

Cultural Policy and Political Oppression: Nazi Architecture and the Development of SS Forced Labor Concentration Camps* Paul B. Jaskot Beyond its use as propaganda, art was thoroughly integrated into the implementation of Nazi state and party policies. Because artistic and political goals were integrated, art was not only subject to repressive policies but also in turn influenced the formulation of those very repressive measures. In the Third Reich, art policy was increasingly authoritarian in character; however, art production also became one means by which other authoritarian institutions could develop their ability to oppress. The Problem We can analyze the particular political function of art by looking at the interest of the SS in orienting its forced labor operations to the monumental building economy. The SS control of forced labor concentration camps after 1936 linked state architectural policy to the political function of incarcerating and punishing perceived enemies of National Socialist Germany.1 The specific example of the Nuremberg Reich Party Rally Grounds reveals three key aspects of this SS process of adaptation. The first aspect is the relationship between architectural decisions at Nuremberg and developments in the German building economy during the early war years. Before the turning tide of the war led to a cessation of work at the site, agencies and firms involved with the design and construction of the Nuremberg buildings secured a steady and profitable supply of work as a result of Hitler’s emphasis on a few large architectural projects. The second aspect focuses on how the SS quarrying enterprises in the forced labor concentration camps were comparable to their private-sector competitors. -

'However Sick a Joke…': on Comedy, the Representation

10 ‘However sick a joke…’: on comedy, the representation of suffering, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Melodrama and Volker Koepp’s Melancholy Stephanie Bird Primo Levi invokes the notion of a joke when he first arrives in Auschwitz. The prisoners, who have had nothing to drink for four days, are put into a room with a tap and a card that forbids drinking the water because it is dirty: ‘Nonsense. It seems obvious that the card is a joke, “they” know that we are dying of thirst and they put us in a room, and there is a tap, and Wassertrinken Verboten’.1 In Levi’s example, the relationship of mocked and mocker is clear, as is the moral evaluation that condemns those that would ridicule and taunt the prisoners. Yet in Imre Kertész’s novel Fateless, the moral clarity offered by Levi is obscured is absent from Kertész’s reference to the notion of a joke. In it, the 14 year-old boy, György Köves, describes how the procedure he and his fellow passengers must undergo from arrival in Birkenau to either the gas chambers or showers elicits in him a ‘sense of certain jokes, a kind of student prank’.2 Despite feeling increasingly queasy, for he is aware of the outcome of the procedure, György nevertheless has the impression of a stunt: gentlemen in imposing suits, smoking cigars who must have come up with a string of ideas, first of the gas, then of the bathhouse, next the soap, the flower beds, ‘and so on’ (Fateless, 111), jumping up and slapping palms when they conjured up a good one. -

Grey Morality of the Colonized Subject in Postwar Japanese Cinema and Contemporary Manga

EITHER 'SHINING WHITE OR BLACKEST BLACK': GREY MORALITY OF THE COLONIZED SUBJECT IN POSTWAR JAPANESE CINEMA AND CONTEMPORARY MANGA Elena M. Aponte A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2017 Committee: Khani Begum, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2017 Elena M. Aponte All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Khani Begum, Advisor The cultural and political relationship between Japan and the United States is often praised for its equity, collaboration, and mutual respect. To many, the alliance between Japan and the United States serves as a testament for overcoming a violent and antagonistic past. However, the impact of the United States occupation and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is rarely discussed in light of this alliance. The economic revival, while important to Japan’s reentry into the global market, inevitably obscured continuing paternalistic interactions between Japan and the United States. Using postcolonial theory from Homi K. Bhahba, Frantz Fanon, and Hiroshi Yoshioka as a foundation, this study examines the ways Japan was colonized during and after the seven-year occupation by the United States. The following is a close assessment of two texts and their political significance at two specific points in history. Akira Kurosawa's1948 noir film Drunken Angel (Yoidore Tenshi) shaped the identity of postwar Japan; Yasuhiro Nightow’s Trigun manga series navigates cultural amnesia and American exceptionalism during the 1990s after the Bubble Economy fell into recession in 1995. These texts are worthy of simultaneous assessment because of the ways they incorporate American archetypes, iconography, and themes into their work while still adhering to Japanese cultural concerns. -

Ward, Kenneth (2017) Taking the New Wave out of Isolation: Humour and Tragedy of the Czechoslovak New Wave and Post-Communist Czech Cinema

Ward, Kenneth (2017) Taking the new wave out of isolation: humour and tragedy of the Czechoslovak new wave and post-communist Czech cinema. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8441/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] TAKING THE NEW WAVE OUT OF ISOLATION: HUMOUR AND TRAGEDY OF THE CZECHOSLOVAK NEW WAVE AND POST-COMMUNIST CZECH CINEMA KENNETH WARD CONTENTS Introduction 2-40 Theoretical Approach 2 Crossing Over: Art Films That Could Reach the Whole World 7 Subversive Strand 10 Tromp L’oeil and the Darkly Comic 13 Attacking Aesthetics: Disruption Over Destruction 24 Normalization and Czech Cunning 28 History Repeats Itself: An Interminable Terminus 32 Doubling as Oppressor 36 Chapter One: Undercurrents and the Czechoslovak New Wave 41-64 Compliance and Defiance 41 A Passion for Diversion 45 People Make the System 52 Rebels Without a Cause 56 Summary 64 Chapter Two: A Very Willing Puppet 65-91 On the Cusp of a Wave 65 A Madman’s Logic 67 Mask of Objectivity -

What's Past Is Prologue: Filming Fascism and the Family in Japan

What’s Past is Prologue: Filming Fascism and the Family in Japan and West Germany in the 1970s Jillian Helena Vasko A Thesis in The Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2017 © Jillian Vasko, 2017 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Jillian Vasko Entitled: What’s Past is Prologue: Filming Fascism and the Family in Japan and West Germany in the 1970s and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: Marc Steinberg Chair Chair’s name Kay Dickinson Examiner Examiner’s name Yuriko Furuhata Examiner Examiner’s name Joshua Neves Supervisor Supervisor’s name Approved by Marc Steinberg Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director August 30th 2017 Rebecca Taylor Duclos Dean of Faculty Abstract: This thesis theorizes the correlation between national historical trauma in Japan and West Germany, and the excessive, gendered and often sexualized violence inflicted upon and by women protagonists in films emerging from these nations in the 1970s. The thesis provides a comparative analysis of two films which investigate the origins of ‘fascism’ in their nation through the allegory of the female protagonist and her relationship to the institution of the family: Toshiya Fujita’s 1973 Lady Snowblood (Shurayukihime) and Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1974 film Martha.