Letras Hispanas Volume 8.1, Spring 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pedagogical Philosophies and Techniques of David Effron

"#$!%$&'()(*+',!%#*,)-)%#*$-!.!"$+#/*01$-!)2!&'3*&!$224)/! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 56! ! *78!%799:;<=! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ->5:?@@=A!@;!@B=!C7D>E@6!;C!@B=! F7D;59!-DB;;E!;C!G>9?D!?8!H7<@?7E!C>EC?EE:=8@! ;C!@B=!<=I>?<=:=8@9!C;<!@B=!A=J<==K! &;D@;<!;C!G>9?D! *8A?787!18?L=<9?@6! &=D=:5=<!MNOP! ! ! 'DD=H@=A!56!@B=!C7D>E@6!;C!@B=! *8A?787!18?L=<9?@6!F7D;59!-DB;;E!;C!G>9?D! ?8!H7<@?7E!C>EC?EE:=8@!;C!@B=!<=I>?<=:=8@9!C;<!@B=!A=J<==K! &;D@;<!;C!G>9?D! ! ! &;D@;<7E!+;::?@@==!! ! ! ! QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ! #7E?87!(;EA5=<JK!4=9=7<DB!&?<=D@;<! ! ! ! ! QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ! '<@B><!27J=8K!+B7?<! ! ! ! ! QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ! F;<R7!2E==S78?9! ! ! ! ! QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ! T7E@=<!#>CC! ! ! U!&=D=:5=<!MNOP! ! ??! ! +;H6<?JB@!V!MNOP! *78!%799:;<=! ???! ! ! !"#$%&&"''(#)%*+,(#%*-#."**/0#1%223"&0(#%*-#4/%**%#5/"&0 ?L! ! !"#$%&#' ! "B=!@<789D<?H@9!H<=9=8@=A!?8!@B?9!A;D>:=8@!<=H<=9=8@!C;><!?8@=<L?=W9K!D;8A>D@=A! 56!@B=!7>@B;<K!W?@B!G7=9@<;!&7L?A!$CC<;8X!"B=9=!?8@=<L?=W9!W=<=!<=D;<A=A!?8!G7=9@<;! $CC<;8Y9!B;:=!?8!ZE;;:?8J@;8K!*/!;8!F>E6!OM@B!78A!F>E6!OU@BK!MNOPX!"B=!@<789D<?H@9!B7L=! 5==8!B=7L?E6!=A?@=A!C;<!@B=!97[=!;C!DE7<?@6!78A!<=7A75?E?@6\@B=6!7<=!8;@!@<789D<?5=A! 60&7%8/3X!2?EE=<!W;<A9!]^>::K!>BK!=@DX_`!78A!E;8J!H7>9=9!?8!9H==DB!B7L=!5==8!<=:;L=A! =8@?<=E6K!79!B7L=!9;:=!;DD79?;87E!L=<57E!@?D9!]^6=7BK!E?[=K!=@DX_`X!2><@B=<:;<=K! J<7::7@?D7E!=<<;<9!9>DB!79!<>8a;8!9=8@=8D=9!B7L=!5==8!^>8@78JE=A_!WB=<=L=<!H;99?5E=X!! '8!;DD79?;87E!=bHE=@?L=!B=<=!78A!@B=<=!B79!5==8!<=@7?8=A!C;<!=bH<=99?L=!<=79;89X!$L=<6! -

Russell-Autobiography.Pdf

Autobiography ‘Witty, invigorating, marvellously candid and generous in spirit’ Times Literary Supplement Bertrand Russell Autobiography First published in 1975 by George Allen & Unwin Ltd, London First published in the Routledge Classics in 2010 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor and Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. © 2009 The Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation Ltd Introduction © 1998 Michael Foot All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalog record for this book has been requested ISBN 0-203-86499-9 Master e-book ISBN ISBN10: 0–415–47373–X ISBN10: 0–203–86499–9 (ebk) ISBN13: 978–0–415–47373–6 ISBN13: 978–0–203–86499–9 (ebk) To Edith Through the long years I sought peace, I found ecstasy, I found anguish, I found madness, I found loneliness, I found the solitary pain that gnaws the heart, But peace I did not find. -

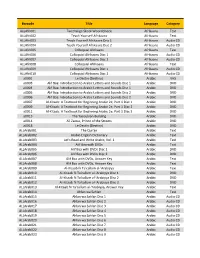

Barcode Title Language Category Allafri001 Tweetalige Skool

Barcode Title Language Category ALLAfri001 Tweetalige Skool-Woordeboek Afrikaans Text ALLAfri002 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri003 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri004 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri005 Colloquial Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri006 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri007 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri008 Colloquial Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri009 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri010 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD a0001 Le Destin (Destiny) Arabic VHS a0003 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0004 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0005 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0006 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0007 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0009 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0011 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 3 Arabic DVD a0013 The Yacoubian Building Arabic DVD a0014 Ali Zaoua, Prince of the Streets Arabic DVD a0018 Le Destin (Destiny) Arabic DVD ALLArab001 The Qur'an Arabic Text ALLArab002 Arabic-English Dictionary Arabic Text ALLArab003 Let's Read and Write Arabic, Vol. 1 Arabic Text ALLArab004 Alif Baa with DVDs Arabic Text ALLArab005 Alif Baa with DVDs Disc 1 Arabic DVD ALLArab006 Alif Baa with DVDs Disc 2 Arabic -

The American Dream As Revealed Through the Characters in Lorraine Hansberry’S a Raisin in the Sun

THE AMERICAN DREAM AS REVEALED THROUGH THE CHARACTERS IN LORRAINE HANSBERRY’S A RAISIN IN THE SUN AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By ANTALASI FEBRISA Student Number: 034214102 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2008 THE AMERICAN DREAM AS REVEALED THROUGH THE CHARACTERS IN LORRAINE HANSBERRY’S A RAISIN IN THE SUN AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By ANTALASI FEBRISA Student Number: 034214102 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2008 i ii iii For to me to live is Christ to die is gain (Philippians 1: 21) Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your God works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven. (Matthew 5: 16) There is always something left to love. And if you ain’t learned that, you ain’t learned nothing. (Lorraine Hansberry) iv v I sincerely dedicate this undergraduate thesis to My beloved Father and Mother My beloved Aunt Herminta My beloved Sister Astrid and Brother Andri My beloved Opa Sukardi in the hope of a better future vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my living Savior Jesus Christ who gives me His love, blessing and guidance. He gives me the capability and the strength in accomplishing my thesis. I would not be able to finish this thesis without Him. -

A Raisin in the Sun Script's Dialogue.P65

Raisin In The Sun Script Better get out of here That’s what you’re mad about. before you be late. Wake up. Things I want to talk to my friends Could I please Come on now, honey. about just couldn’t be important. go carry groceries? Get up! Such friends as you got. Honey, you should play evenings. Come on. You look young this morning, baby. What’s he want to do? It’s 7:30. Just for a second, stirring Carry groceries after school I said, hurry up, Travis. them eggs, you look real young again. at the supermarket. You’re not the only person It’s gone now. Let him go. It’s good for him in the world got to use a bathroom. to be business-minded. You look like yourself again. Walter Lee, it’s after 7:30. I have to. If you don’t shut up She won’t give me the 50 cents. Let me see you do and leave me alone... some waking up in there now. Why not? The first thing a man should learn... You just go ahead Because we don’t have it. and lay there. ...is not to make love to no woman early in the morning. What do you tell the boy Next, Travis’ll be finished things like that for? and Mr. Johnson’ll be in. You all are some evil creatures 8:00 in the morning. Here you are, son. And you’ll be fussing and cussing like a madman and be late. Daddy, come on! In fact.. -

Question Paper 34 Pages

www.XtremePapers.com UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE INTERNATIONAL EXAMINATIONS International General Certificate of Secondary Education LITERATURE (ENGLISH) 0486/04 Paper 4 May/June 2007 2 hours 40 minutes Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *4148319455* READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST If you have been given an Answer Booklet, follow the instructions on the front cover of the Booklet. Write your Centre number, candidate number and name on all the work you hand in. Write in dark blue or black pen. Do not use staples, paper clips, highlighters, glue or correction fluid. Answer four questions. Answer at least one question from each section. Each of your answers must be on a different book. Answer at least one passage-based question (marked *) and at least one essay/empathic question. At the end of the examination, fasten all your work securely together. All questions in this paper carry equal marks. This document consists of 31 printed pages and 5 blank pages. SP (NH) T31588/2 © UCLES 2007 [Turn over 2 BLANK PAGE 0486/04/M/J/07 3 CONTENTS Section A: Drama text question numbers page(s) Lorraine Hansberry: A Raisin in the Sun *1, 2, 3 pages 4–5 Liz Lochead/Gina Moxley: Cuba and Dog House *4, 5, 6 pages 6–7 William Shakespeare: As You Like It *7, 8, 9 pages 8–9 William Shakespeare: Macbeth *10, 11, 12 pages 10–11 George Bernard Shaw: The Devil’s Disciple *13, 14, 15 pages 12–13 Tennessee Williams: A Streetcar Named Desire *16, 17, 18 pages 14–15 Section B: Poetry text question numbers page(s) Samuel Taylor Coleridge: from Selected Poems *19, -

Gender and Turkish-German Cinema

From Margins to the Center Through the Film Lens: Gender and Turkish-German Cinema Filiz Cicek Submitted to the Faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department The Department of Central Eurasian Studies, Indiana University December, 2012 Accepted by the Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee: Chair: Professor Cigdem Balim Harding, Ph.D Emeritus Professor Gustave Bayerle, Ph.D Professor Paul Edward Losensky, Ph.D Professor Jennifer Elizabeth Maher, Ph.D Professor Colin J. Williams, Ph.D Date of Dissertation Defense: November 2, 2012 ii Copyright © 2012 Filiz Cicek iii To My Little Sparrow who left this earth all too untimely. To My family and Friends. To My Committee Members. To all the Others. iv Preface The knowledge that isn’t transformed into compassionate wisdom is useless thinking. Hindu proverb. I come from the East, the Middle East, from the oral tradition of story telling and record keeping in memory. And I have been living in the West, where most everything is written down, intended for posterity. East might have been East and West West for Kipling, but they have been meeting in continued fluidity in my life and in my work for the past twenty years by necessity of a life as an immigrant. It was in the silent hiking with my grandmother, up and down the Caucasus Mountains. It was in the voice of my 110-year old great-grandmother, chiming her stories from the potato ditch where she was hiding from the Russians. -

Documento De Trabajo Para La Cop18 De La

Idioma original: inglés CoP18 Doc. 71.1 CONVENCIÓN SOBRE EL COMERCIO INTERNACIONAL DE ESPECIES AMENAZADAS DE FAUNA Y FLORA SILVESTRES ____________________ Decimoctava reunión de la Conferencia de las Partes Colombo (Sri Lanka), 23 de mayo – 3 de junio de 2019 Cuestiones específicas sobre las especies Grandes felinos asiáticos (Felidae spp.) INFORME DE LA SECRETARÍA 1. Este documento ha sido preparado por la Secretaría. 2. En el párrafo 2 a) de la Resolución Conf. 12.5 (Rev. CoP17), sobre Conservación y comercio de tigres y otras especies de grandes felinos asiáticos incluidos en el Apéndice I, la Conferencia de las Partes encarga a la Secretaría que: a) presente al Comité Permanente y a la Conferencia de las Partes un informe sobre la situación de los grandes felinos asiáticos en el medio silvestre, su conservación y los controles del comercio establecidos por las Partes, utilizando información facilitada por los Estados del área de distribución sobre las medidas adoptadas para cumplir esta Resolución y las Decisiones pertinentes conexas, así como cualquier otra información pertinente facilitada por los países afectados. 3. En su 17a reunión (CoP17, Johannesburgo, 2016), la Conferencia de las Partes adoptó inter alia las Decisiones 17.224 a 17.231 sobre Grandes felinos asiáticos (Felidae spp.), como sigue: Dirigida a las Partes 17.224 Se invita a todas las Partes que se haya indicado que son motivo de preocupación en la Decisión 17.229 a que acojan con beneplácito una misión de la Secretaría para visitar los establecimientos que mantienen grandes felinos asiáticos en cautividad. Dirigida a las Partes y a las organizaciones intergubernamentales y no gubernamentales 17.225 Se alienta a las Partes, las organizaciones intergubernamentales y las organizaciones no gubernamentales a que brinden apoyo financiero y técnico a las Partes que soliciten capacidades y recursos adicionales para aplicar de manera eficaz la Resolución Conf. -

00 Preliminares INGLÉS+.Qxd 29/5/06 10:39 Página 3

“Although Spain began to rid herself of a good many of her complexes with the arrival of democracy,and she might even be said to have swung the other way entirely and become one of the most liberal countries in Europe,one would also expect ,spain, her to lose her inhibitions in the promotion of her brands”. Vicente Verdú a culture “Today,the Spanish language is synonymous with a growing, expanding market [...] Learning Spanish as a second language is all the rage in the top East Coast universities”. brand Fernando R.Lafuente From Altamira to leading brands “The brands of the companies of a particular country and of its products and services are essential for determining its reputation and its social,cultural and technological image in the rest of the world”. Guillermo de la Dehesa “In Spain,there is a series of companies that the internation- al media in this sector call “the New Spanish Armada”. Covadonga O’Shea Published by the Leading Brands of Spain Association Sponsored by: Leading Brands of Spain 00 Preliminares INGLÉS+.qxd 29/5/06 10:39 Página 3 ,spain, a culture brand From Altamira to leading brands Leading Brands of Spain 00 Preliminares INGLÉS+.qxd 29/5/06 10:39 Página 5 contents 6 Prologue José Montilla Aguilera, Minister of Industry, Tourism and Trade 8 Presentation José Luis Bonet, Chairman of the Leading Brands of Spain Forum 10 The Leading Brands of Spain Forum I. Innovation and tradition Vicente Verdú 17 There’s no business like top brand business Mariano Navarro 55 The art brand II. -

Merchant, P. (2017). Rhetorics of Chilean Cinema (Pablo Corro, 2014). Film Studies, 16(1), 94-102

Merchant, P. (2017). Rhetorics of Chilean Cinema (Pablo Corro, 2014). Film Studies, 16(1), 94-102. https://doi.org/10.7227/FS.16.0008 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.7227/FS.16.0008 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via ingenta connect at This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via [insert publisher name] at [insert hyperlink]. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Rhetorics of Chilean Cinema (Pablo Corro, 2014) Paul Merchant (University of Cambridge) Introduction The circulation of theoretical ideas about cinema across national and linguistic boundaries is uneven and unpredictable. It is intriguing to note, for example, that much literature in the field, especially work associated with the continental tradition of thought,1 is translated into Spanish and published in Latin America before reaching the Anglophone market. Such is the case for some of the writings of Georges Didi-Huberman, Jean-Luc Nancy, and most importantly for the purposes of this extract, for those of Gianni Vattimo, whose concept of ‘weak thought’ is central to Pablo Corro’s analysis of the poetics of Chilean film. -

Immigration in Context: a Resource Guide for Utah

Immigration in Context: A Resource Guide for Utah The University of Utah Honors Think Tank On Immigration 1 176818 U of U.R1 1 5/8/07 10:56:50 AM 176818 U of U.R1 2 5/8/07 10:56:51 AM FOREWORD INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................................3 HISTORY AND NATIONAL LEGISLATION...................................................................................................5 HISTORY OF IMMIGRATION AND THE UNITED STATES........................................................................5 A TIMELINE.....................................................................................................................................................8 AN IN-DEPTH VIEW......................................................................................................................................13 The Chinese Exclusion Act...........................................................................................................................13 Bracero Program..........................................................................................................................................14 Operation Wetback.......................................................................................................................................15 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).......................................................................................16 ECONOMIC AND FISCAL IMPACT OF IMMIGRATION..........................................................................22 -

Neon Calico Joshua Webb Garrett Eastern Illinois University This Research Is a Product of the Graduate Program in English at Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Neon Calico Joshua Webb Garrett Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Garrett, Joshua Webb, "Neon Calico" (2016). Masters Theses. 2715. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2715 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EAS"11'1<.,"1lLLINOIS UNIVERSITY'" Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis.