The Melammu Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

The Fragmentation of Being and the Path Beyond the Void 2185 Copyright 1994 Kent D

DRAFT Fragment 48 THE HOUSE OF BAAL Next we will consider the house of Baal who is the twin of Agenor. Agenor means the “manly,” whereas Baal means “lord.” In Baal is Belus. Within the Judeo- Christian religious tradition, Baal is the archetypal adversary to the God of the Old Testament. No strange god, however, is depicted more wicked, immoral and abominable than the storm god Ba’al Hadad, whose cult appears to have been a great rival to Yahwism at certain times in Israel’s history. In the bible we read how the prophets of Ba’al and Yahweh persecuted and killed one another, and how the kings of Israel wavered in their attitudes to these gods, thereby provoking the jealousy of Yahweh who tolerated no other god beside him. Thus, it appears that the worship of Ba’al Hadad was a greater threat to Yahwism than that of any other god, and this fact, perhaps more than the actual character of the Ba’al cult, may be the reason for the Hebrew aversion against it. The Fragmentation of Being and The Path Beyond The Void 2185 Copyright 1994 Kent D. Palmer. All rights reserved. Not for distribution. THE HOUSE OF BAAL Whereas Ba’al became hated by the true Yahwist, Yahweh was the national god of Israel to whose glory the Hebrew Bible is written. Yahweh is also called El. That El is a proper name and not only the appelative, meaning “god” is proven by several passages in the Bible. According to the Genesis account, El revealed himself to Abraham and led him into Canaan where not only Abraham and his family worshiped El, but also the Canaanites themselves. -

ANGELS in ISLAM a Commentary with Selected Translations of Jalāl

ANGELS IN ISLAM A Commentary with Selected Translations of Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī’s Al-Ḥabā’ik fī akhbār al- malā’ik (The Arrangement of the Traditions about Angels) S. R. Burge Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2009 A loose-leaf from a MS of al-Qazwīnī’s, cAjā’ib fī makhlūqāt (British Library) Source: Du Ry, Carel J., Art of Islam (New York: Abrams, 1971), p. 188 0.1 Abstract This thesis presents a commentary with selected translations of Jalāl al-Dīn cAbd al- Raḥmān al-Suyūṭī’s Al-Ḥabā’ik fī akhbār al-malā’ik (The Arrangement of the Traditions about Angels). The work is a collection of around 750 ḥadīth about angels, followed by a postscript (khātima) that discusses theological questions regarding their status in Islam. The first section of this thesis looks at the state of the study of angels in Islam, which has tended to focus on specific issues or narratives. However, there has been little study of the angels in Islamic tradition outside studies of angels in the Qur’an and eschatological literature. This thesis hopes to present some of this more general material about angels. The following two sections of the thesis present an analysis of the whole work. The first of these two sections looks at the origin of Muslim beliefs about angels, focusing on angelic nomenclature and angelic iconography. The second attempts to understand the message of al-Suyūṭī’s collection and the work’s purpose, through a consideration of the roles of angels in everyday life and ritual. -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too. -

Divine Principle & Angels (V1.6)

Divine Principle & Angels Introduction v 1.6 Recense of an Angel Artist Benny Andersson Introduction • This is an attempt to collect what the Bible and Divine Principle and True Father has spoken about Angels. • Included is some folklore from the Unif. movement. You decide what’s true. Background • The word angel in English is a blend of Old English engel (with a hard g) and Old French angele. Both derive from Late Latin angelus "messenger of God", which in turn was borrowed from Late Greek ἄγγελος ángelos. According to R. S. P. Beekes, ángelos itself may be "an Oriental loan, like ἄγγαρος ['Persian mounted courier']." • Angels, in a variety of religions, are regarded as spirits. They are often depicted as messengers of God in the Hebrew and Christian Bibles and the Quran. • Daniel is the first biblical figure to refer to individual angels by name, mentioning Gabriel (God's primary messenger) in Daniel 9:21 and Michael (the holy fighter) in Daniel 10:13. These angels are part of Daniel's apocalyptic visions and are an important part of all apocalyptic literature Orthodox icon from Saint Catherine's Monastery, representing the archangels Michael and Gabriel. Along with Rafael counted as archangels of Jews, Christians and Muslims. • The conception of angels is best understood in contrast to demons and is often thought to be "influenced by the ancient Persian religious tradition of Zoroastrianism, which viewed the world as a battleground between forces of good and forces of evil, between light and darkness." One of these "sons of God" is "the satan", • a figure depicted in (among other places) the Book of Job. -

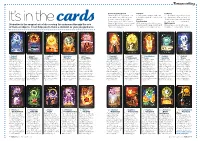

Fortune Telling

Fortune telling How to use the spread Intuition Dowsing Relax and focus on the question Slowly open your eyes and then Using a pendulum, ask it to show you want to ask - this can be as select the card that you feel most you a movement for ‘yes’ and ‘no’. general or specific as you like. drawn to. Then hover it over each card until It’s in the Then, using one of the following Psychometry you get a ‘yes’ - this is your card. forms of divination, choose a card With your eyes closed, run your Bibliomancy Divination is the magical art of discoveringcards the unknown through the use and read the summary you have hand across the page and stop at Close your eyes and with your of tools or objects. It can help you to make a decision or give you guidance chosen for guidance. the card you feel is right for you. finger point to any card at random. Gabriel Hanael Jophiel Metatron Uriel Zaphkiel Jophiel Sandalphon Zadkiel Gabriel 1 Balance 2Willpower 3 Joy 4 Miracles 5 Friendship 6 Surrender 7 Forgiveness 8 Love 9 Security 10 Grace Gabriel wants you to The great whales of The card you have Miracles are changes Uriel wishes you to The angels want you to Jophiel asks you to let This angelic oracle The angels unite The oracle of Gabriel know that you have the oceans deep are chosen brings forth a of perception and know that the true know that you are go of the pain of the comes to you as with their powerful wishes you to receive been too busy. -

Archangel Kindle

ARCHANGEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sharon Shinn | 10 pages | 01 Dec 1997 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780441004324 | English | New York, United States Archangel PDF Book She has a great love of nature, people, and the planet, and she enjoys her connection in spirit, both here and in heaven. The energy of the mouse is quiet productivity of the multitudes, while the groundhog digs deeper for answers and represents the world of dreams, the opossum represents family nurturing, and the skunk and raccoon represent the cleanup crew. Any time you or someone you love is experiencing sadness due to loneliness, call on Archangel Uriel to help to see the wonders that exist within your soul or the soul for whom you are praying. Know that the reality, is there are far more Archangels serving behind the scenes. Michael the Archangel. Become a fundraiser to help us collect, clone, archive the genetics, and replant these important trees for future generations. These cookies do not store any personal information. In this book I provide many guided meditations audio and experiments that help you discover more ways to deeply connect with Michael. In human form, Raquel appears with wings in flowing white robes and a large book in hand. Additionally, this Archangel symbolically appears in the form of fish, representing the fluidity of divine communications, situations of divine emotional importance, and the surreal world of dreams. Moscow Official as Yakov Rafalson. External Reviews. Uriel presents three impossible riddles to show us how humans cannot fathom the ways of God. Archangel Jophiel provides assistance with refocusing on positive experiences of life, encouraging inner journeys which lead to the discovery of soul-specific solutions for your life's passions, and raising your energy levels and thoughts toward the light to inspire the giving and receiving of unconditional love. -

1 2 9/10/00 Isiah 46-48 the Prophet Isaiah Now Deals with The

1 2 9/10/00 b) Daniel himself was given a pagan name identified with their god, Isiah 46-48 Belteshazzar. Dan. 1:7 c) The posture describes one of false The prophet Isaiah now deals with the punishment gods who are tottering, of Babylon for her idolatry, her pride and how * The prophet has already said that these very gods will not help the people of Judah. every knee is going to bow . Is. 45:23 This is the recurring subject of the book but and a 2) The second god is Nebo or Nabu, was the major focus of the second division of Isaiah, which son of Bel, which means “the revealer or is evident from chapter forty to the present one. speaker”, the god of writing, equivalent to the Hebrew word “Nabi”, meaning Some say that the Babylonian captivity taught the prophet. vs. 1a nation of Israel regarding idolatry but if you a) He served the same function as did examine the book of Ezra and Nehemiah, you will Hermes for the Greeks or Mercury for see that they were guilty of idolatry after the the Romans. Acts 14:12 captivity. b) He also was thought to be the bearer of the tablets of destiny of the gods”. 46:1-4 The ironic comparison between the c) The temple of Nebo stood at gods of Babylon and the Eternal God. Borshippa and the temple of Bel was at Babylon. 46:1-2 The Babylonian gods had to be d) Again the name of this god was used carried. -

A N G E L S (Amemjam¿) 1

A N G E L S (amemJam¿) 1. Brief description 2. Nine orders of Angels 3. Archangels and Other Angels 1. Brief description of angels * Angels are spiritual beings created by God to serve Him, though created higher than man. Some, the good angels, have remained obedient to Him and carry out His will. Lucifer, whose ambitions were a distortion of God's plan, is known to us as the fallen angel, with the use of many names, among which are Satan, Belial, Beelzebub and the Devil. * The word "angelos" in Greek means messenger. Angels are purely spiritual beings that do God's will (Psalms 103:20, Matthew 26:53). * Angels were created before the world and man (Job 38:6,7) * Angels appear in the Bible from the beginning to the end, from the Book of Genesis to the Book of Revelation. * The Bible is our best source of knowledge about angels - for example, Psalms 91:11, Matthew 18:10 and Acts 12:15 indicate humans have guardian angels. The theological study of angels is known as angelology. * 34 books of Bible refer to angels, Christ taught their existence (Matt.8:10; 24:31; 26:53 etc.). * An angel can be in only one place at one time (Dan.9:21-23; 10:10-14), b. Although they are spirit beings, they can appear in the form of men (in dreams – Matt.1:20; in natural sight with human functions – Gen. 18:1-8; 22: 19:1; seen by some and not others – 2 Kings 6:15-17). * Angels cannot reproduce (Mark 12:25), 3. -

![[1821-1891], "Assyrian and Babylonian Inscriptions in Their](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7898/1821-1891-assyrian-and-babylonian-inscriptions-in-their-1657898.webp)

[1821-1891], "Assyrian and Babylonian Inscriptions in Their

.ASSYRI.AN AND B.ABYLONI.AN INSCRIPTIONS. 275 Man was to him an eternal ministry; it had never been closed by death, for death itself had been superseded by resurrection. To the mind of the Apostle, the history of the past had no need yet to be written ; for the past was to him still the present. The things of yesterday had, for him, no distinctive or peculiar interest ; for the Being whom he recognized as the Founder of Christianity was one whom he could have described, in the language of one of his own school, as "the same yesterday, and to-day, and for ever." G. MATHESON. ASSYRIAN AND BABYLONIAN INSCRIPTIONS IN THEIR BEARING ON THE OLD TESTAMENT SCRIPTURES. V. NIMROD AND THE GENEALOGY OF GENESIS X. IT is at first a somewhat surprising result of the studies of Assyriologists, that as yet no certain trace has been discovered of one whose name has been, from a very early period, prominent in many of the legends and traditions that gather round the history of Assyria. No interpreter has yet identified any combination of cuneiform characters with the name of Nimrod.1 Whatever explanation may be given of the fact, it at all events bears testimony to the caution and accuracy of the interpreters as a body. Few temptations would have been greater to an imaginative scholar than that of discovering, if it were possible, even at some sacrifice of the precision which is an element of a 1 Mr. George Smith, however (R. P., ill. 6), finds the name NIN·RIDU on a brick in the British Museum, as that of the guardian deity of Eridu, one of the earliest Babylonian cities. -

The Identification of Belus with Cronus in Nonnus’ Dionysiaca 18.222–8

Miszellen 429 His fretus Suetoni et Plutarchi locos aptissime cohaerere censeo: Caesaris hospes per errorem pro bono oleo („viridi“) supra asparagos unguentum („oleum condı¯tum“) fudit; Caesaris comites rem talem, utpote inurbanam, Leonti quasi ob- iciebant; tum Caesar consuluit ne hospitis error argueretur. Pisis Carolus Martinus Lucarini THE IDENTIFICATION OF BELUS WITH CRONUS IN NONNUS’ DIONYSIACA 18.222–8 There is an instance of Belus being identified with Cronus in the Dionysiaca of Nonnus of Panopolis (5th c.), but it has not heretofore been recognized. In the eighteenth book Dionysus visits the Assyrian king, Staphylus, who encourages the god by telling him a story of the Titanomachy and the monsters sent against Zeus. ‘Assyrian Belus’1 is mentioned at the beginning of this story, though all modern edi- tors, following Cunaeus2 have rearranged the introductory lines in various ways, but consistently so as to make Belus the grandfather of Staphylus and the original narrator of the story3. The character of Belus is treated inconsistently in the rest of the epic, in book 3 Belus, referred to as ‘the Libyan Zeus’, is the son of Poseidon and Libya, and the grandfather of Cadmus4, but in book 40 Belus is treated as the Assyrian name for the Sun as a god5 (Cronus and Zeus are said to be other names of the Sun). Reference to these passages cannot, therefore, help us toward a proper reading of Belus in book 18, but does demonstrate that in Nonnus ‘Belus’ refers to no single character, neither human nor divine. If we assume, however, that Nonnus in this passage identified the Assyrian god (/king - ?) Belus with the Cronus of traditional Hellenic myth, we are able to maintain the order of the lines as it is found in the manuscripts: 1) Dionysiaca 18.224. -

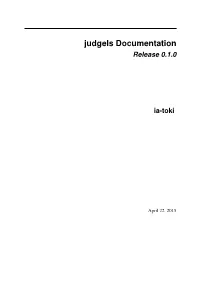

Judgels Documentation Release 0.1.0

judgels Documentation Release 0.1.0 ia-toki April 22, 2015 Contents 1 Introduction1 1.1 Applications...................................1 1.2 License......................................2 1.3 Contributions...................................2 2 Setup 3 2.1 Requirements...................................3 2.2 Installation....................................4 2.3 Configuration...................................4 3 Single Sign On (Jophiel)5 3.1 Configuration...................................5 3.2 Running Jophiel.................................5 3.3 Jophiel User Roles................................5 3.4 Single Sign On Protocol.............................6 3.5 Future Target...................................6 4 Programming Repository (Sandalphon)7 4.1 Configuration...................................7 4.2 Running Sandalphon...............................7 4.3 Sandalphon User Roles..............................8 4.4 Client’s Problem Rendering...........................8 4.5 Future Target...................................8 5 Problem Types9 5.1 Blackbox Grading................................9 5.2 Constraints....................................9 5.3 Evaluators....................................9 5.4 Problem Types.................................. 10 5.5 Creating Checker................................. 11 6 Message Oriented Middleware (Sealtiel) 13 6.1 Configuration................................... 13 6.2 Running Sealtiel................................. 13 6.3 Message Queue.................................. 13 i 6.4 Polling.....................................